Between sides: Juhan Kuus, “The Measure of Humanity”

Juhan Kuus “The Measure of Humanity. 45 Years of Documentary Photography in South Africa” at Adamson-Eric Museum, in Tallinn

14/10/2016

The exhibition “The Measure of Humanity”, presenting the work of South African photojournalist Juhan Kuus, was opened on 19 August 2016 at the Adamson-Eric Museum in Tallinn. The reason why this comprehensive overview of the internationally known photojournalist Juhan Kuus, who was born and worked in South Africa, is being exhibited in Tallinn, is because he is of Estonian descent. His popularity, however, was unknown in the local Estonian cultural scene until one of the exhibition’s curators, the documentary filmmaker Toomas Järvet, accidentally came across Kuus’ name and work while researching artists of the Estonian diaspora. One of the aims of the exhibition is to give Juhan Kuus and his legacy a worthy place in the cultural scene and cultural history of Estonia, even though this legacy is based on South African culture and history.

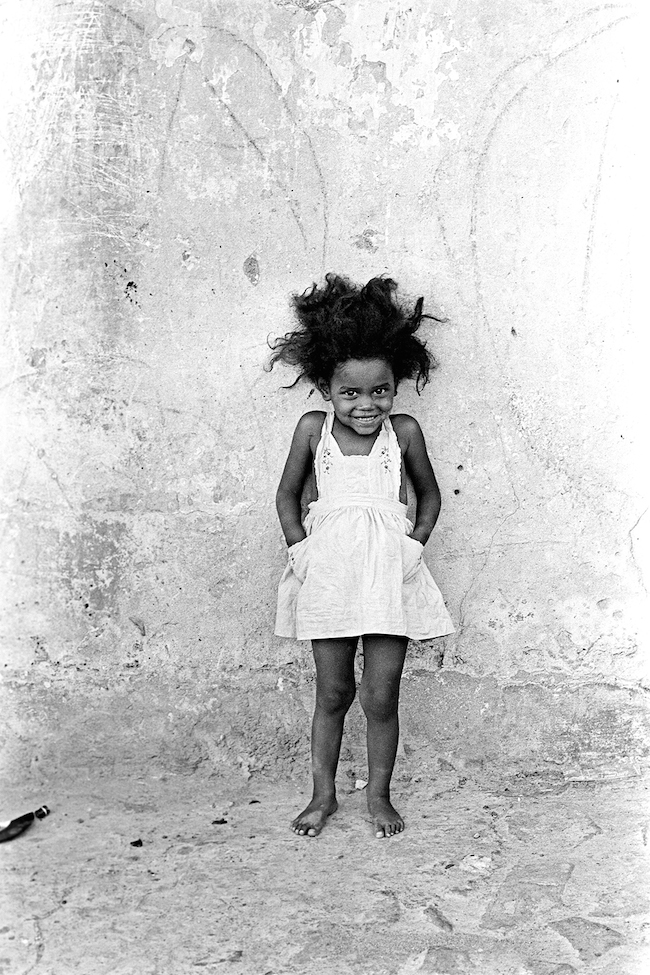

A girl poses against a wall for a photograph, at the historical Muslim Malay Quarter of Bo-Kaap Upper Cape Town, South Africa. 1973

When in the moment, it might be quite difficult to differ between what is “right” and what is “wrong”; only in retrospect are we allowed to judge views, actions and beliefs. It is also complicated, looking at Juhan Kuus, to analyze his work and the situation in a country which should be the Rainbow Nation. In some ways, his controversial personality might have been the reason why his photographs were recognized, and later on – resented, by other internationally known photojournalists. Juhan Kuus worked as a photographer for 45 years, starting from age 17; he received many awards, including the South Africa Press Photographer of the Year and, as the exhibition’s organizers point out, he is the only person of Estonian descent to have ever received the World Press Photo Award, which he won in both 1978 and 1992. His photos have been published in newspapers such as The Times, The Independent, The New York Times, etc.

Anti-apartheid unrest, Cape Town, South Africa. 1985. “Civil disobedience on the streets of the Cape Town central business district after the police suppressed the Pollsmoor march to demand the release of Nelson Mandela earlier in the week.”

Kuus’ work and achievements have been divided by the curators into three periods. The first period in his career might be dated from 1969 to 1986, during which time he started working as a darkroom assistant, and later on, as a junior photographer for the South African newspaper Die Burger. He changed newspapers a few times before becoming a freelance photographer. In the 70s and 80s he captured the complicated social-political situation and its transformation: apartheid segregation of the people, and repressive politics against black people.

The second period in his work started in 1986, when he started working for Sipa Press, and ended in 2000, when his contract there was terminated. (Sipa Press is a photo agency founded in 1976 by Turkish photographer and journalist Gökşin Sipahioğlu.) This period is important in South African history because of the fight for democracy and the massacres and violence at the beginning of the 90s. At the same time, this period was also one of the most covered news stories around the world, with many internationally known photographers working in South Africa. Juhan Kuus received the highest recognition of his career at this time, taking photos of everything that happened, sometimes even getting attacked himself. Besides reporting the news, he also took pictures of everyday life and people.

One of the most popular quotes concerning war photography and conflict journalism is by Robert Capa: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough”. Juhan Kuus' pictures are there; they are close, but they don’t judge – rather, they analyze the situation and society. Taking pictures of white and black people, taking pictures of political rallies and mundane life, taking photos of poor and homeless people, taking photos of the rich, taking pictures of the abused and their abusers. His work, as it is also stated in the exhibition’s catalog, is a mirror of society, showing its beauty as well as its ugliness. It takes it as it is and just presents its reflection, even if it is not a good reflection; for example, photos of violence against people. Ever since the Vietnam War, photojournalists have been capturing moments showing things that people never knew about war and violence. And looking at South Africa around that time, Juhan Kuus, along with other photojournalists, captured and showed situations that people weren’t aware of in other parts of the world.

A coloured down-and-out woman in Cape Town, South Africa. April 1976

The last period of his work is dated from 2000 to 2015, which is when he unexpectedly passed away. After the termination of his contract with Sipa Press, he continued to work and take pictures, documenting the people around him. This period seems also to be the most mysterious time concerning his work as a photojournalist, because the necessity for photojournalism to ask for comments and reports on political situations in conflict zones from different places around the world increased at that time. Also, South Africa wasn’t the “top” news story anymore. Juhan Kuus started to lose recognition, and had less work to provide to the news agencies. The question that arises, taking into account his abilities, is why he didn’t go to different news agencies, and why he didn’t become a correspondent in different places in the world. And here, one could come to Juhan Kuus' controversial personality. At the peak of his career, one thing that did set him aside from other conflict photographers is that he carried a gun, which made other photographers resent him and his working method.

A man with his neutered dog. The Animal Rescue Organization, Du Noon township, Cape Town, South Africa. 2001

After his stint at Sipa Press, he continued to photograph people; he continued to capture people’s lives after South Africa became democratic. One of the subjects of his work is poor and homeless people, and he himself also lived in shelters and sold his cameras and lenses just to able to buy film and to continue his work and projects. By looking at his photographs, one can see his dedication to reflecting and showing. Most of the works in the exhibition have short descriptions of the depicted situation, written by Juhan Kuus. This makes the experience of viewing more personal – it gives the viewer the opportunity to become acquainted with the person, as well as with other peoples' worlds and realities, without the possibility of objectifying it. Kuus stayed devoted to people and the culture from where he came, and that devotion does show in his work.

As stated in the exhibition’s catalog, after the exhibition’s curators got in contact with Juhan Kuus and met him in 2014, in Paris, it was decided to make a comprehensive personal exhibition in Tallinn. He was very excited about this, but in the end, after his unexpected death, the exhibition became instead a retrospective in memorium exhibition. Something that started as a project to introduce to the local Estonian culture a person who is world-renown, as well as to give him the possibility of visiting his father’s country of birth, turned into a thorough and retrospective exhibition that now marks his posthumous legacy.

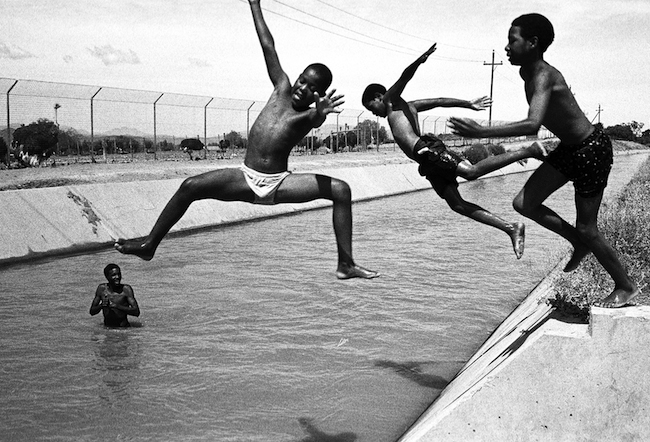

First day of the school holidays and 33 degrees Celsius; children from Bridgton township cool off in an irrigation canal near the abbatoir

South Africa. 8 December 2003

Looking at the exhibition and the photos taken by Juhan Kuus, the exemplary work that has been done by the curators and the exhibition’s organizers needs to be noted. One of the missions that they set for themselves was to introduce Estonians to Juhan Kuus and his work – to introduce his subject matter and the world as he saw it. This part of the exhibition was executed with a very well-organized strategy stressing the public’s point of view. First of all, there were advertising posters set up all around Tallinn and also on social media sites. Also, his works and information about him was posted in public spaces, for example, at Tallinn’s central bus station and in Old Town, allowing passersby to see parts of the exhibition and actually “get to know” this quite remarkable photographer and his work. This approach by the organizers not only introduced Kuus as a photographer, but also introduced South Africa and its history to the public – which for some, as it is so far away, might be completely unknown.

But at the same time, the exhibition does raise questions concerning what we do know about social-political situations in other parts of the world. Overly concerned with analyzing the recent history of our region, how much do we know about repressions, violence and injustice anywhere else in the world? Juhan Kuus' photographs have a place in documenting history, but do they creep into the “art world”? Looking at this side of the exhibition, it does raise this question: If the exhibition is happening in an Estonian art museum, does it mean that it counts as art? In the exhibition’s catalog, Juhan Kuus is cited as saying: “I am not an artist, I am a photographer. I photograph the imperfections of humanity that are lovable. For me, photography is about people on the margins of society.” Nevertheless, Juhan Kuus' photographs have an aesthetic quality, even if they do depict the most horrific things. His talent in photography opens the doorway to other peoples' lives. It also raises an ethical question: Can we call other peoples' suffering a work of art?

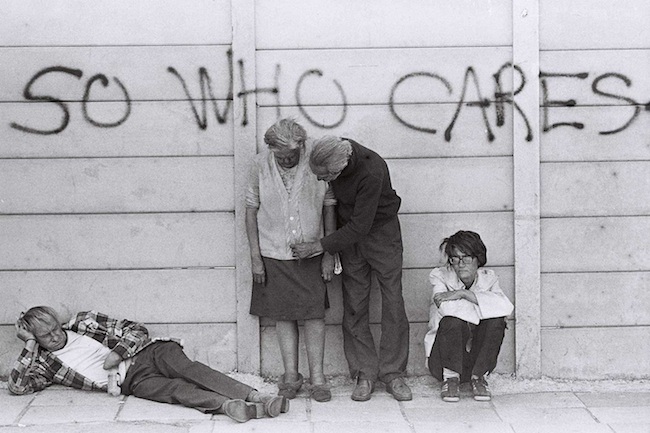

So Who Care, Johannesburg, South Africa. 6 April 1983

The exhibition doesn’t give measurements of humanity, but it does give a way in which we can rethink values, beliefs and worries. Humanity can’t be measured. The same way that one can’t decide if something is “right” or “wrong” within different social conditions and contexts that influence one or the other choice. Only in retrospect is it possible to evaluate reasons and actions. Therefore, Juhan Kuus' exhibition educates us and makes us analyze our understanding of the world.