From reproduction of the visible to conveying the intangible

Olga Abramova

30/11/2016

Gerhard Richter. Abstraction and Appearance

Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre, Moscow

9 November 2016 – 5 February 2017

When Paul Moorhouse, Senior Curator of 20th Century Collections at the London National Portrait Gallery and the curator of the first Russian exhibition by Gerhard Richter, was asked why he had not brought any of the famous figurative paintings to Moscow, his answer came almost straight from Kozma Prutkov (the parodic fictional Russian poet invented by Alexey Tolstoy et al.): It is impossible to encompass the boundless.

The living classic, the super star of German art will very soon be marking his 85th birthday anniversary. Over the course of his long life and career, he has managed to accomplish so much and confused the viewers and critics with so many unexpected stylistic turnarounds that representing ‘the whole Richter’ is indeed a mammoth task of which only giants like Beaubourg (Centre Georges Pompidou), inaugurated in 1977 with his show, the likes of the Louvre, Tate Modern, МоМА or the Basel-based Beyeler Foundation, all of which have hosted extensive Richter retrospectives, are capable.

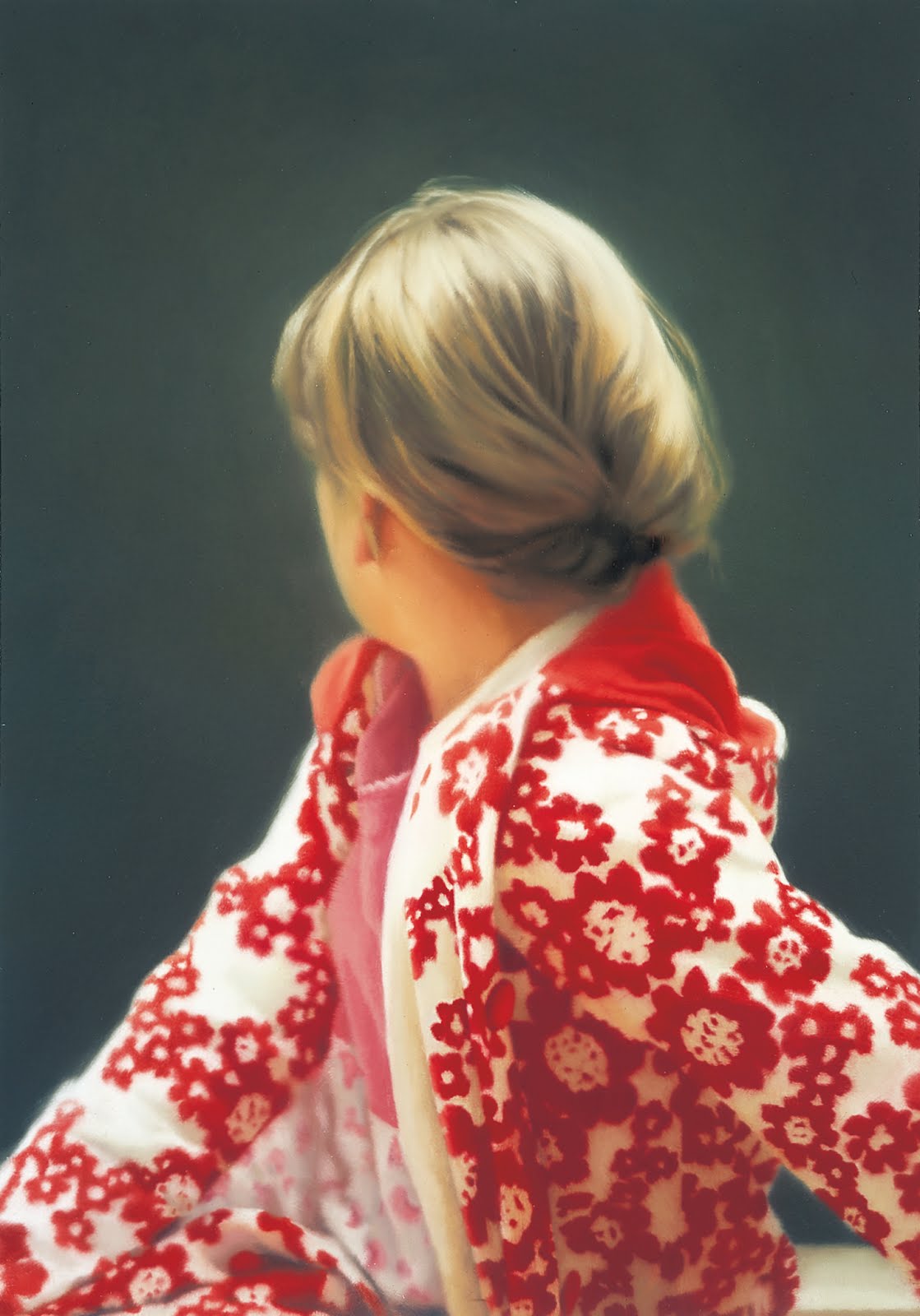

Gerhard Richter. Betty. 1988

We may yet experience an event like that sometime in the future; the present occasion, however, is a special one in a somewhat different way: the German master is welcomed by the Jewish Museum, and the curator and the artist are telling the story of an almost half-century’s worth of creative explorations, centring the perfectly arranged exhibition around a project directly referencing the tragedy of the Holocaust.

Born in 1932, Richter experienced the war as a child; as a teenager he witnessed the post-war Germany ‒ the ‘heap of rubbish’, according to a contemporary journalist, ‘teeming with 40 million hungry Germans’ ‒ and, like the majority of his countrymen capable of reflective thinking, was forever scarred by a profound psychological trauma. Having found himself by an accident of fate in East Germany, Richter went on to study at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, famous for its academic traditions, and even painted the odd Socialist Realist mural. In 1955, Richter first saw Paris, while in 1959, at II. documenta in Kassel, he discovered for himself abstract art and the road from ‘reproduction of the visible to conveying the intangible through images’. In 1961, almost immediately following a visit to the USSR and on the eve of the erection of the Berlin Wall, Richter moved to Düsseldorf, where he continued his studies and where his life as an artist started for real. While exploring various art practices in the spirit of Neo-Dada and Pop Art, Richter was trying to find his own way: even back then he believed that sitting around, thinking about what it was that you actually wanted to create was complete nonsense. You simply have to do one thing or another.

What this ‘one thing or another’ turned out to be for Richter was initially his ironic Capitalist Realism (Kapitalistischer Realismus) project that dealt with images of mass media and mass culture and prompted him to embrace a meaningful relationship with the art of photography and a quest to find the answer to the fundamental question of the 20th-century art: should it, in this age of mechanical reproduction as defined by Walter Benjamin, attempt to copy the visible world? And where, in the case of a negative answer, lies its true objective?

Gerhard Richter. Aunt Marianne. 1965

From the mid-1960s, Richter was working in the intersection between photography and painting: compiling an archive of amateur photographs and using the pictures as a basis for his canvases. With the help of photography, he was still looking to define his relationship with the reality, so diligently emulated by classic art. For Richter, reality is something intangible and unreliable: ‘I don’t mistrust reality, of which I know next to nothing. I mistrust the picture of reality conveyed to us by our senses, which are imperfect and circumscribed.’ Photography, mechanically capturing whatever was taking place, became the sole reality for the artist. He reproduced it with great skill, marking the ambiguousness of the image with blurs, transitions and flares. These painterly ‘interferences’, killing the concreteness, awaken imagination, empathy and reflection. The artist here is like a good book illustrator who does not impose on the reader a single possible visual solution, creating the right mood instead.

Photo painting did more than just bring Richter proper fame for the first time: it also allowed the artist to do some work on his own incomplete gestalts. Using photos from his own personal archive, Richter painted his Uncle Rudi, a Wehrmacht officer who died at the end of the war, and Aunt Marianne, a mental patient killed by the Nazi as part of their eugenics programme. The blurred, vibrating images seem to be dissolving in space and time ‒ or, on the contrary, attempting to materialize again in vain. The individual features disappear, they are displaced, transforming into a vague memory that is not subject to moral evaluation.

Gerhard Richter. Uncle Rudi. 1965

In the 1970s, following the Venice Biennale, where Richter was allotted a whole pavilion for his project of 48 portraits, and Harald Szeemann’s revolutionary documenta 5, abstraction and colour came to Richter’s painting. Initially it was the colour grey as the antipode of all things colourful, ‘the only possible equivalent for indifference, noncommitment, absence of opinion, absence of shape’; later it was followed by all the colours of the rainbow.

And now is the moment to go back to the space of the Moscow exhibition: all the main heroes of the show ‒ photography, abstraction, colour ‒ are in place already, and the earliest of the pieces featured at the exhibition has just about been born. The title of the canvas, pastosely covered in abrupt transverse brush strokes of thick grey paint, is just that ‒ ‘Grey’ (1973).

Gerhard Richter. Grey. 1973

The grey period in Richter’s painting lasted several years, like a breather in the chase after the ever-elusive reality: after all, an abstract painting lives according its own rules; it is concentrated within the plane of the canvas, its surface and texture. A bit later the grey surface acquired mystical depth in giant grey mirrors, one of which is now also ready to reflect the Moscow viewer. And then, allegedly by accident, a drop of paint fell on a photo print, and the seemingly antagonistic phenomena ‒ surface and depth; image and abstraction ‒ engaged in an unexpected and strikingly impressive interaction.

The overpainted photographs once again gave relevance to Richter’s musings regarding the nature of reality; the birth of appearance; image and abstraction. More than two thousand pieces have been created since the mid-1980s. Two series illustrating the diverse potential of this practice have been brought to Moscow. The original photographs of the ‘Grey Forest’ (2008) are covered in thick brush strokes of dark varnish, almost completely obscuring the trees and the grass, evoking a disturbing sensation of a disappearing wildlife. The varnish covering the amateur prints in ‘Museum Visit’ (2011) is vibrantly red; the photographic image and the non-figurative half-transparent smudges together create a new structure and a new image.

Gerhard Richter. Haggadah. 2006

The mature Richter is defined by painterly abstraction as a curtain, hiding or revealing the image hidden in the depths of the picture; multilayeredness; the presence or a feeling of presence of the figurative element. His painting is becoming increasingly virtuoso and decorative; he comes up with all sorts of aids and tools, like a rubber pallet knife used to apply, move around, spread and scrape off paint, making it shimmery and intricately iridescent, like in the glistening and pearly ‘Haggadah’ (2006), named after a sacred Jewish text. He pours paint over a surface and then observes the free movement of colours creating various unpredictable combinations to make them freeze at exactly the right moment ‒ like in the ‘Aladdin’ series of paintings on glass (2010). He paints his multilayered and thick ‘Abstract Painting’ (2016) on small wooden planks. Sometimes it may seem that the artist has forgotten all about settling his scores with reality, surrendering himself completely to the visual power of colour. After all, his early experiments with coloured squares, brilliantly manifested in the stained-glass window he made for the Cologne Cathedral, were not a coincidence.

Gerhard Richter. Abstract Painting. 2016

The ‘Birkenau’ project (2014), the centre of the current exhibition, puts everything back in its proper place. It is a consistent and convincing reproduction of the artist’s work on creating a painterly ‘analogy for something non-visual and incomprehensible’. In the role of the incomprehensible Richter casts a tragic episode of the Second World War dealing with the extermination camp where more than a million people met with their death. The project comprises four photographs dating from 1944, secretly taken by a Jewish inmate from the camp’s Sonderkommando; four large paintings based on the photographs; four photo prints the size of the canvases, and 93 digital prints of fragments. Layer after layer, the artist has put on the canvas a charcoal drawing reproducing the photograph; a black-and-white underpainting emulating the monochrome colour scheme of the original; then, one by one, the colour layers with references to the blackness of the earth, the crimson of blood and the off-white and ripples of green of the birch grove from which this hell-like place got its name. The resulting abstract paintings would be difficult to read correctly in absence of the relevant photographic document. It is easy to detect the influence of the Dadaist and Abstract Expressionist painting practices in the pictures. However, the conceptual installation, explicitly arranged by the artist, will not permit anyone to evade this truth, no matter how deeply buried under the thick layers of colour.

The Birkenau project (2014) in Moscow

The light-hearted old detective movie ‘The Affair of Thomas Crown’, alongside depictions of Magritte characters and clever thieves, contains an amusing scene where a teacher, desperately attempting to restore discipline among a restless group of kids who find the museum boring, tells them: look, this picture is worth a million dollars, and the children, intrigued, finally calm down. How wonderful that the Moscow exhibition by the most successful of living contemporary artists is capable of capturing the viewer with more than just mentions of huge amounts of money. Meanwhile, the record sum paid at an auction for a piece by the German master amounts to not just one but rather forty-six million dollars.