Something hyper

23/12/2016

Herkki-Erich Merila “Hyperpolis”

Tallinn Art Hall, Tallinn (Harju 13)

Through 8 January, 2017

Herkki-Erich Merila’s photography exhibition “Hyperpolis” opened on 9 December at the Tallinn City Gallery. Herkki-Erich Merila is an Estonian photo-based artist. As the press release suggests, alongside his art projects, he is also known for his press and fashion photography. In contrast to his fashion photography, which is more concerned with clothes and products as a subject, his art frees human bodies from this burden. Although his artistic projects bring together naked bodies with architectural forms, in the exhibition “Hyperpolis” human presence and human bodies disappear from the architectural surroundings, only appearing as accidental silhouettes from afar.

The subject of the exhibition is Chongqing – a mayor city in Southwest China. One of the five national central cities, administratively it is one of China’s four direct-controlled municipalities alongside Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin. It is believed to be one of the emerging megacities in China with around 30 million inhabitants living in what is a 2000-year-old settlement.

In his photographs Herkki-Erich Merila approaches the city and the urban landscape avoiding any human presence as if it were a ghost town. However, the first thing that is interesting about this exhibition is its title. The word hyperpolis cannot be found in any dictionaries, but at the same time it speaks for itself. Referring to large cities or conurbations, people normally use terms such as megacity, metropolis or megalopolis. To be called a megacity, a city needs to have 10 million inhabitants. In that case, the question is ‒ what word can we use speaking about even larger cities? In this case, however, it is possible to understand the meaning of the word. The title consists of two words: Hyper- that is used as a prefix for a noun to indicate that something is more than normal or too much of something, and polis, a greek word that means “city”. Therefore, the title “Hyperpolis” reveals the subject of Herkki-Erich Merila’s photographs even before viewing the exhibition.

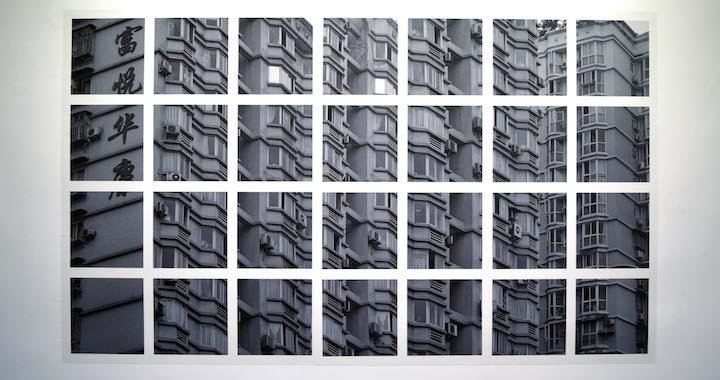

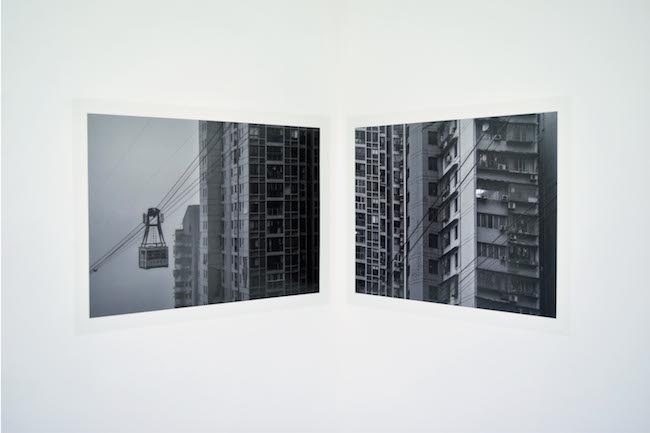

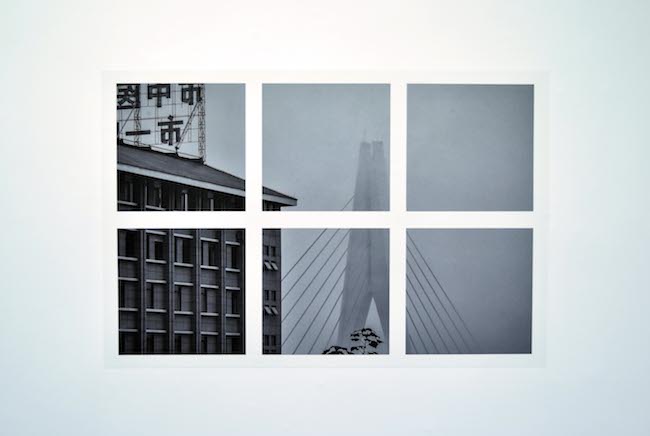

The exhibition consists of black-and-white photographs displayed throughout the two-room gallery. As the title of the show suggests, the exhibited photographs depict block houses, modern urban areas with skyscrapers, bridges, advertisements and houses that look like they are about to collapse at any moment. Photographs taken from rooftops or other high vantage points capture the fog, and some of the buildings disappear into the sky. In every photograph there are countless apartment windows and balconies. So many windows, so many hidden lives, so many stories.

Even though the atmosphere of the photographs evokes a sense of emptiness, it is still possible to see human silhouettes in the windows. It seems that there is no-one there, but if you look closely at the pictures, you start noticing silhouette after silhouette. We cannot see directly into the apartments, and yet it feels as if we were unintentionally peeking into other people’s lives. Clearly the photographs were not taken to depict people. Judging by the exhibition text, it seems that the artist wants to escape it altogether, but that is not really possible. Somehow the foggy feeling in the pictures, the places that the photos are taken from, the angle of the shots, the lights in the apartments invite the viewer to look inside. It awakens a feeling of curiosity about what is behind those windows. And yet the very fact of choosing to capture a man-made environment has made it impossible to avoid the human presence in every shot: even if we cannot see them there, we know that the buildings weren’t made by nature. Unconsciously we are aware that someone is or has been there, either in the past or the present. Interestingly, even though the photographs seem to follow each other in a row, some of them are connected and create a puzzle-like feeling: the brain connects the separate parts; meanwhile, other photos remain just the way they are.

However, the show is exactly what one would expect from a contemporary photography exhibition: large format photographs on the walls at approximately the same level as in a white cube gallery; every wall of the space is covered; on every wall there are photographs without frames. They are glued to the wall, almost as if blending in with the colour of the wall. The exhibition is also complemented by a sound installation and, just for the opening, there was also a smoke machine. The sound part of the exhibition seemed a bit unnecessary and even a bit predictable. First of all, it has been done before: for example, not very far from the building, at the previous exhibition of Tallinn Art Hall’s Gallery, Vytenis Jankūnas' “Stuck on the Train”, where photographs were supplemented with the sound of people on a train. The sound installation in Merila's exhibition with the traffic, people, porn soundtrack makes the subject and the photos seem superficial. In a way, it is not about the photos and the aesthetic approach to the photos anymore but about something different instead ‒ as if the people avoided in the photographs were present in the sound. In a way, the sound seemed to not have a purpose. If the artist is steadily decreasing the presence of humans, why would he want to bring them back via their sound? It seems that the soundtrack is there just for the sake of a currently popular trend in art exhibitions.

Surely photographing the blockhouses and high-rises of a large city in black-and-white, in a way that makes it seem like there are no people, might need some extra kick for the viewers to understand what it is about. The foggy feeling in the pictures had already created the atmosphere in the exhibition; in some ways, the sound and the smoke machine diverted attention from the artworks. It created a feeling that our imagination was not allowed to pick up these things on its own ‒ that we as viewers needed extra help with special effects to understand what it was about. The photos speak for themselves. The effects are not necessary, because in some ways Herkki-Erich Merila's skilful photographing fills this gap and you can see the deliberation with which the work has been done. Selecting every part of the photograph, the light, the space, everything, he has created a disturbed reality in the sense that it is something we don’t expect to see when faced with a megacity – the absence of people. Every photograph is a bit distorted in some unique way. This is very intriguing and creates the feeling that all the photos are part of some bigger picture. But is there a purpose behind it or is it just to make it look interesting?

Even though I do think this is quite a compelling exhibition, it creates a feeling of uncertainty as to the message, narrative or statement that the artist wants to make. Has it been done on purpose or is it just a certain popular way of exhibiting photographs? Something about the photographs does seem to reference fashion photography, which concerns itself with the newest and coolest things in the world of consumerism; it is meant to be popular. In some ways, it shines through ‒ the popular, the pretty, the aesthetic; something that would appeal to the many. Even though it is visually appealing and interesting, somehow it lacks the depth of meaning. Maybe it lacks a narrative.

The other concern with the exhibition is the text and some of its slightly exaggerated claims. It states that even though the photographer usually stages his images, in the photographs that were made for this exhibition, he is almost entirely non-intrusive behind the camera. The concept of “non-intrusiveness” while taking photos is something that has been discussed a lot concerning photography. Analysing other visual arts, we understand that the creation of an artwork is not something accidental, whereas photography somehow creates an illusion that the artist captures the moment and does not interfere with the act of creation. Selecting the subject of a photograph is a choice and therefore already an intrusion into the reality that continues. Capturing a certain moment on film or an SD card is a choice and an interference in the moment. Even though in the exhibition we are presented with certain images that represent a certain way of seeing, it is intrusive, because we as the viewers cannot see whether the artist took a single picture and left, or he waited and waited, tried and changed positions to get the perfect shot.

In her book “On Photography” Susan Sontag writes, “In deciding how a picture should look, in preferring one exposure to another, photographers are always imposing standards on their subject. Although there is a sense in which the camera does indeed capture reality, not just interpret it, photographs are as much an interpretation of the world as painting and drawings are.”[1] Every photographer intervenes with their subjects, with the outcome of the photographs. Even using different programs to improve the images or distort them is already an act that changes the original shot. The interesting thing about statements like these is that in one way or another, photographs are staged; they represent the photographer's choices, their interests, their subjects and what the future exhibition, magazine or press viewer will see – what they are meant to see. Photographs aren’t just something that happens. Even just the act of pressing the camera button means that the artist has chosen to depict a certain thing. He has a vision of what he wants to show in the future, therefore, because of the photographer’s involvement, he needs to take responsibility. Herkki-Erich Merila presents his way of seeing.

The compelling part of the exhibition is that it is something exotic and can’t be related to Tallinn, or anywhere in the Baltics for that matter, but at the same time one can relate to the photos themselves. The difference lies in the number of people who live in block house areas. In the end, an exhibition that seems very interesting has been filled with too much energy and became hyper. Similarly to the title of the exhibition “Hyperpolis”, one can sort of understand the intent of the artist, but it is more complicated than it tends to show.