From Selfie to Self-Expression at the Saatchi Gallery, London

Estere Kajema

12/04/2017

From Selfie to Self-Expression

Saatchi Gallery, London SW3

Through May 30, 2017

Let’s agree – there is absolutely nothing new about taking a selfie. There’s nothing new about putting it on a screen, about sharing it with your friends and family, or even sharing it with a bunch of complete strangers. The act of taking a selfie and posting it online is so common that in 2013, the word “selfie” officially became a listing in the Oxford Dictionary. Through different times and periods in the history of the world and the history of art, the notion of self-representation has been moving forwards – from self-portrait as self-recognition (found, for instance, in cave paintings), to self-portrait as a bourgeois state of mind.

Excellences & Perfections, Amalia Ulman’s selfie-based art work. Credit: Arcadia Missa/Amalia Ulman

On the last day of March 2017, the Saatchi Gallery, located in West London, celebrated the opening of their new exhibition titled From Selfie to Self-Expression. As advertised, the show is a result of collaborative work between the Saatchi Gallery and Huawei, a Chinese company that produces screens and smartphones, and it celebrates the abnormally popular medium of self-expression known as the selfie. Gallery director Nigel Hurst claims that this exhibition is the world’s first exhibition exploring the history of the selfie.

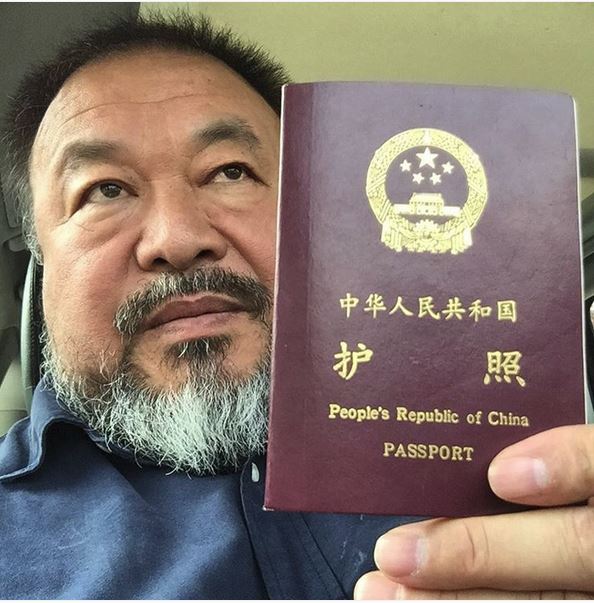

The official Oxford Dictionary definition of “selfie” is “A photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and shared via social media.” Still, there is a practical difference between a selfie and a self-portrait. Whilst the idea of a self-portrait could imply many different techniques, a selfie seems to be much more straightforward and does not imply much intellectual or artistic labor. Even though books are being written about the “art” of the selfie, and exceptional artists, including Amalia Ulman and Ai Weiwei, use a selfie technique in their work, taking a selfie is still not considered to be a high-class beaux-arts skill.

Photo: Ai Weiwei (@aiww) via Instagram

When entering the first two gallery rooms at Saatchi, a visitor finds themselves surrounded by dozens of large Huawei screens, all presenting images of classical paintings – beginning with Rembrandt and ending with Frida Kahlo. Spectators are given the opportunity to vote for the best classic “selfie” by pressing a “like” button on a smartphone that is connected to the larger screen. It is natural that, at the end of the day, it is up to the spectators themselves to decide what kind of art they really like, but it also seems eerie and somewhat degrading to give them an opportunity to cast a “vote” between such excellent but very different artists.

The second gallery room is dedicated to postmodern and contemporary artists who, using different methods, search for ways of self-representation. In this room, the spectator sees digital reproductions of works by Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat; the latter, instead of painting a figurative portrait of himself, usually painted a large black figure with blurred, or even completely absent facial features. This gallery room also includes unique Cindy Sherman prints, including Untitled Film Still #21, one of Sherman’s sixty-nine photographic self-portraits in which she poses as a traditional female character from various American films of the 1970s.

Hitler in París, 1940. Photo from Heinrich Hoffman collection

One of the topics that is explored in the exhibition is the issue of dangerous and extreme decisions that some individuals choose to make whilst taking a selfie. As very precisely pointed out by Jean Pigozzi in his 2014 interview with , the essence of making a selfie is that it can often act as an object of ultimate and unconditional evidence. Pigozzi says that nowadays, instead of asking a celebrity for an autograph, it is more common to ask them for a shared selfie. This is also very common with those who take selfies in extreme situations, for instance, when climbing a tall abandoned tower, or when swimming next to a predatory shark, or even while driving at high speed. There is no better evidence than a quick, unedited selfie. In the same room, the viewer will also see selfies that have been made in front of beautiful panoramas, or in iconic places; these, too, correspond with Pigozzi’s observation. Everyone is familiar with the infamous photograph of the German conquerors – Adolf Hitler and his friends, Albert Speer and Arno Breker, posing in front of the Eiffel Tower in Paris – a photograph that almost seems to scream out loud: “We’ve got it! It’s ours!” It seems that selfies in front of Niagara Falls, the Egyptian pyramids or Big Ben convey a similar message – indeed, in a much less politically aggressive tone, but nevertheless, the selfie still stands for visual testimony, an exhibitionist check mark on one’s bucket list for everyone to see and for everyone to like.

.jpg)

Alison Jackson. From Mental Images series, 2016

From Selfie to Self-Expression gives the viewer a unique chance to see three artworks by Alison Jackson, a truly exceptional contemporary British artist whose work is especially significant today, in the era of Trump. One of the most important questions that she is working on is whether we can believe the images that the media forces us to see, and subsequently, the rabid desire of the viewer or reader to see everything and to know everything. In this exhibition, the spectator is offered to see three works by Jackson, all of which are part of the series of work called Mental Images. Jackson casts lookalikes to pose in front of her camera, to either recreate or to act out a scene from, in this case, the lives of Donald Trump and the British Royal Family. The eerie similarity between the actors and the actual people that we see in the media every day is truly disturbing, but what is even more daunting is that all of the scenes that have been manufactured in Jackson’s work could, in fact, be very real. For instance, in the photograph of a Donald Trump lookalike taking a selfie using a selfie stick with three Miss Universe competition contesters, the lookalike has a phone case with the words “Make America Great Again” written in white against the red background, in exactly the same manner as the slogan that was advertised during Trump’s presidential campaign. The message is: Don’t trust everything you see, but on the other hand, don’t fully doubt it, either.

Juan Pablo Echeverri. Miss Fotojapón. Daily passport photos. Since June 2000 (work in progress)

Since 2000, the Columbian-born artist Juan Pablo Echeverri has been taking daily passport photos for the art project Miss Fotojapón. Every day, the artist goes to a passport photo booth and takes a photograph of himself; it seems that through this repetitive, almost performative way of working, the artist is truly able to create a self-portrait – because, indeed, an understanding of one’s own representation and a sense of identity is something that is formed over time, rather than instantaneously. By taking self-portraits every day for the past seventeen years, Echeverri is able to track the changes that his body is naturally going through.

The exhibition also includes several artworks that were programmed to automatically interact with the spectators, for example, the work by Mexican artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer and Polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko: inside a gallery room, the duo has installed twelve computerized surveillance cameras that use a face recognition algorithm in order to identify and separate the individual viewers of the installation. The robotic cameras zoom in on faces, and the images that they are able to track are broadcast on large wall-sized projections, which clearly makes the spectators in question feel extremely uncomfortable. The idea of this installatrumption is to underline the fact that, in one way or another, automatic face recognition systems are constantly controlling and recording anybody who lives in a city that uses CCTV surveillance systems. Being caught off guard and seeing an involuntary, so-very-awkward and degradingly sudden image of oneself on a large screen makes a spectator realize the deep distance existing between a feeling of self-acknowledgement and a representation of an individual by society and its disciplines.

Dawn Woolley. The Substitute (holiday), 2017

The Saatchi Gallery is very well known for giving young and emerging artists a chance to show their work, and this time they commissioned ten young British photographers to participate in the exhibition. They were asked to create a piece of work using the new Huawei smartphone with a dual lens, which was co-engineered with Leica.

Together, Huawei and Saatchi also launched the competition #SaatchiSelfie, in which anybody could upload a selfie; ten finalists received a new Huawei P10 smartphone, and the overall winner was awarded a joint trip with a Leica Photography Ambassador on an international photo shoot. According to the exhibition’s press release, they received more than 14,000 submissions from over 113 countries. The photographs of the ten shortlisted winners can be seen in the exhibition, as well as the overall winning selfie by Dawn Woolley, which she titled Substitute (Holiday), 2017.

The exhibition is exactly what it is advertised to be, so before visiting Saatchi on a sunny April afternoon, one should keep in mind that one is not actually going to see any artworks by Frida Kahlo or Rembrandt, and that at the end of the day, From Selfie to Self-Expression was intended to be a collaboration between Saatchi and Huawei; and that sometimes, the curatorial decision to present non-digital artworks on a screen might seem unnecessary, and even frustrating, to those who would rather visit the National Gallery or one of the Tate galleries to appreciate the originals. Nevertheless, visiting From Selfie to Self-Expression is a unique opportunity to see a couple of rare Cindy Sherman prints, an installation by Gavin Turk titled “Pop”, and even the life-sized sculptural works by Tim Noble and Sue Webster that were recently on view at Blain Southern Gallery on Maddox Street. But then, seeing Velazquez’s “Las Meninas”, Frida Kahlo's “Self-Portrait with Thorns”, and dramatic self-portraits by Basquiat on large screens, inside the gallery space, feels somehow unnatural.

Finnian Croy. © Finnian Croy, 2017

Sarah Carpenter. Torn. © Sarah Carpenter, 2017

Patrick Gonzales. Untitled - #4. © Patrick Gonzales, 2017