Art Sightseeing

Review: “The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in the New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” at Kumu

21/10/2017

The exhibition “The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in the New Art from Central and Eastern Europe”, curated by Magdalena Moskalewicz, is currently going on in the 5th-floor exhibition space at Kumu through 28 January 2018. This exhibition presents a wide range of contemporary artists from Eastern and Central Europe as it deals with a subject that is important in the context of recent history in the post-socialist and post-Soviet parts of Europe.

Already the title of the exhibition introduces the subjects that will be dealt with in the exhibition, as well as the time frame – from the fall of the Iron Curtain to the present day. The exhibition’s concept gives the artists the opportunity to reflect on the subject from both personal experience and the political reasons for traveling, non-traveling, or migration. This exhibition, with such a title and subjects, seems interesting from several points. One of the first to come to mind is the ever-present question of migration and immigrants entering Europe from East and North Africa, and the media-built hysteria and the political inability to do something to resolve the situation. This idea is also expressed in the exhibition’s accompanying text: “Europe’s response to foreign refugees shows that our participation in the global exchange was, and is, predominantly one-way. We do not willingly share the privileges that we gained after the fall of the Berlin Wall and as a consequence of our EU accession. We are enthusiastic about going abroad, but far less so about welcoming foreigners.”[1] Secondly, the exhibition seems to take control over the outdated idea of Eastern European art by specifically not showing it as peripheral art in contrast to Western art, but rather as an equal entity. By combining historical events with social contemporary issues, the exhibition and the curator have taken a very confident step towards changing already existing stigmatic thoughts about art in this part of the world. This approach could also be seen as a dialogue between East and West that discusses the historical reasons behind traveling and non-traveling experiences in the post-socialist and post-soviet countries. At first glance, this exhibition seems to both represent thorough research into the subject and present a wide range of contemporary artists, yet upon further study, there are some things that don’t seem completely thought through.

One of the best parts of the exhibition are the artworks. Twenty-four artists present twenty-seven artworks dealing with the subject of traveling or migration. The twenty-seven works have been divided into seven parts, or chapters, which was occasionally evident in the positioning of the artworks in the space; however, in most cases, this division can only be understood by reading the exhibition catalogue. Even though the usual practice is to group artworks under similar subjects, the exhibition catalogue doesn’t give reasons for the category titles or why specific works have been grouped into a certain category: The Politics Versus Politics of Travel, Global Circulation, Dreams of Space, Between East and West: Artistic Peregrinations, Postcolonial and Postsocialist Exchanges, Nationalism and Exile, Figure of Migrant. These titles give a narrative and context in which to see the works. From one point of view, it is understandable to point out the different ways of seeing migration or traveling and the differences in experience; however, if the viewer doesn’t have the catalogue, it is impossible to keep track of the differences between these supposedly important contexts.

If all of the above-mentioned issues could somehow be explained away as not being truly problematic, there would, for me, still be one major, unsolvable issue left: how much time should one spend at the exhibition? Is the exhibition meant to be quickly consumed with a passing glance? Or is the exact opposite true? These were the questions I thought about after several shorter visits to the exhibition. However, knowing that this exhibition consists of many long video works, I wanted to see them all, from beginning to end. I calculated that this would take me four and a half hours; but after five hours, I still hadn’t managed to see all of the works. Every video work in the exhibition has its qualities, therefore, it is basically necessary to watch each one from beginning to end. Some are only seven to ten minutes long, but others go from half an hour to a maximum of 82 minutes. In total, the exhibition has nine video works as well as Karel Kopliment’s installation “Case No 13. Waiting for the Ship of Empties” (2017), which also contains a video recording of a performance that takes some time to watch. My calculation of four and a half hours was based only on the lengths of the videos as stated in the catalogue; my estimate didn’t include looking at any of the non-video artworks at the exhibition.

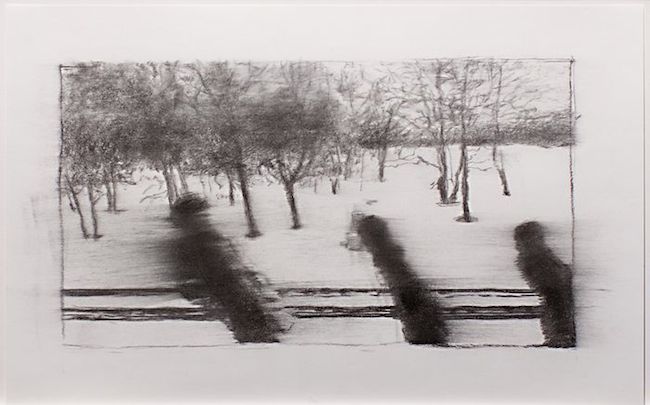

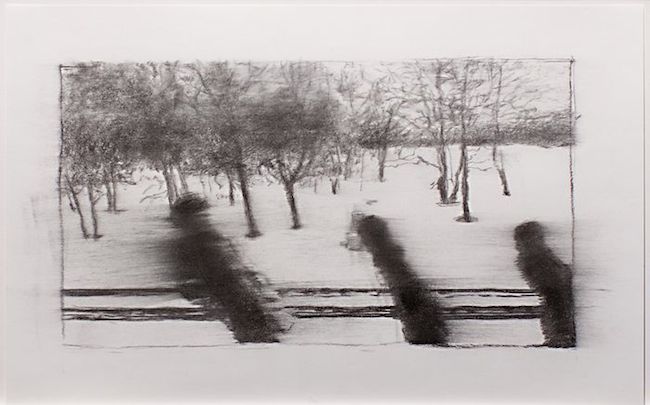

Olga Chernysheva, Briefly. 2013, Drawing series, charcoal on paper, 37 × 59 cm each, Private collection of Irina and Maris Vitols, Riga, Latvia

In this large-scale exhibition, among the relatively large amount of works there are some that stand out more than others. For example, upon entering the exhibition space, one of the first things that the viewer is drawn to is Olga Chernysheva’s work “The Train” (2003). The artist has filmed the process of going through train cars, from one carriage to the next. The video is accompanied by a soundtrack featuring Mozart’s Andante, Concerto for piano and Orchestra No. 21 in C Major, which creates a very poetical atmosphere. Even though the author of the catalogue points out that: “Made more than a decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union, this poetic and, at times, surreal film disturbingly evokes the hopelessness of the era”, I certainly didn’t feel that as I watched the work. This work did not disturb me nor did it instill a sense of hopelessness. The work might very well just depict reality, and the opinion stated in the description seems to be subjectively reflecting a Eurocentric world perception rather than the actual meaning of the work, i.e., everything needs to be shiny and new. Compared to the other works, this one was short and easy to immerse oneself in.

Vesna Pavlović, Fototeka. 2013/2016, From Fabrics of Socialism series, photographic installation, Courtesy of the artist

The other works, however, took more time to get into, such as Vesna Pavlovic’s work “Fototeka” (2013/2016). It is a photographic installation in which the artist projects onto a big gray curtain eighty archival photographs documenting the foreign travels of the Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito. The photographs change from tourist snapshots of architecture to photos of propagandist celebrations by the regime. The gray-colored curtain was apparently inspired by the stage design of official communist events, as well as serving as a reference to the Iron Curtain. It is interesting that one can’t see the photographs clearly on the curtain because the curtain itself has been lit with stage lighting. The problem with this work is that the slide projector changes the images so slowly that you see ten photographs in five minutes; once again, one needs to patiently watch the work for 40 minutes to see it all. No chairs are provided for those who wish to calmly watch the slide show, and there is nothing to indicate that one should actually do so.

Adrian Paci’s video “The Column” (2013), under the chapter Global Circulation, had a similar effect on me. The work surprised me both conceptually and visually, but it took time to watch the 26-minute long video from beginning to end in order to understand the quality and value of the work. Not only are the conceptual aspects of the work interesting, but also the execution of the video has been thoroughly thought through. The video depicts the creation of a column by highly-skilled Chinese workers on a ship. The idea is explained in the catalogue so: “The classical column, based on the models of ancient Rome, was executed in quality marble by highly-skilled Chinese workers, thus complicating the common perception that goods ‘made in China’ are merely cheap fakes.” [2] Much like Chernysheva’s work, this piece can be watched again and again in a loop – it is simply mesmerizing. However, as it takes time to watch the video, most people will spend only a few minutes watching it before they leave the room. Maybe the “made in China” idea of quick and cheap consumption fits in here, too, in the sense that it doesn’t really matter whether or not the viewer watches the work from beginning to end. The question is, are we able to watch works from beginning to end?

Karel Koplimet’s two works, “Case No 11. TALSINKI” (2016) and “Case No 13. Waiting for the Ship of Empties” (2017), are compelling both visually and conceptually. Both case studies, even though not exhibited together, are connected to each other. The first one consists of two video projections of people coming off a ferry. The artist looks into the phenomenon of many Estonians going to Finland to work mostly low-skilled jobs, whereas Finnish tourists travel to Estonia to consume and transport cheap alcohol. Not only does he look at the idea of Estonians going to Finland to work and Finns coming to Tallinn to party, but by using the case-study style, he expresses a certain seriousness in his approach to the documentation. This is especially apparent when we look at the raft which, at first, doesn’t seem connected to anything because it has been placed in the atrium and not on the 5th floor with the rest of the exhibition. The dedication of the artist is impressive – not only to talk about or present a conceptual idea, but to also create a raft from beer cans gathered in Finland, and then actually travel with it back to Tallinn.

C.T. Jasper & Joanna Malinowska, Halka/Haiti 18°48’05″N 72°23’01″W. 2015, Multichannel video projection, 82 min, Collection of Zachęta—National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, Project curated by Magdalena Moskalewicz for the Polish Pavilion at the 56th International Art Exhibition—la Biennale di Venezia

After going through the many rooms of the exhibition, the penultimate one contains C.T. Jasper & Joanna Malinowska’s “Halka/ Haiti 18°48'05''N 72°23'01''W” (2015). The interesting part of the work is its special placement and 180° video projection of an old Polish opera played to Haitian villagers on the street in the mountain village of Cazale in Haiti. In a way, this work is surreal because of both the environment in which it takes place and the intrinsic concept of the work. The work wasn’t created for the exhibition since it had already been exhibited at the 56th Venice Biennale at the Polish National Pavilion. Altogether the video work, which is more like a feature film in terms of length, takes an hour and a half to watch. Even though there were comfortable chairs to sit in and enjoy the work, by the time the viewer reaches this point in the exhibition it is quite difficult to watch from beginning to end. Are we really meant to watch it, or does the exhibition expect a quick hit-and-run attitude towards video art? The work is also accompanied by a half-hour documentary on the preparation for the opera and interviews with the artists’ Haitian collaborators and audience. Again, as much it would be interesting to see the documentary, is it meant to be seen?

Lastly, the final room of the exhibition, which at first glance looks like one installation and is divided between two different titles – “Nationalism and Exile” and “Figure of a Migrant” – is, in fact, four unrelated works combined together in one small space. Even after reading the concepts of each work, the issue is that some of the works literally overshadow the others. Which means that putting so many works together in such a small space doesn’t seem right. The final room consisted of Alban Muja’s “My Name, Their City”, Roman Ondák’s “Casting Antinomads”, Dushko Petrovich’s “El Oso Carnal”, and Daniel Baker’s “Copse”. At first I thought it was one installation that could be seen as one artist reflecting on the subject through different media. However, only upon subsequent visits to the exhibition did I understand that there were, in fact, three artists presenting there. And now, as I am writing this review and going through the catalogue, I understand that there were actually four artists presenting their works in that one space. The space is so small that the works disappear and lose any meaning they may have had on their own. Of course, this would be fine if the works were initially meant to be cramped together and overlapping each other, with the specific intent of making the viewer perplexed and confused.

My issue with the exhibition is that by putting so many artworks together, it enforces quick consumption. You won’t have time to actually look into it at all. You won’t be able to experience all the works. You read about something, assume what it will be about, and then continue on. There is too much information being presented, and one can become tired even after seeing only half of the exhibition. If the goal of the exhibition is to watch all of the works (if the works are, indeed, meant to be watched at all), then the space and environment don’t support this. The chairs, or even sometimes the lack of chairs, don’t allow people to sit down and really enjoy the works for the full time that each one requires.

Has the watching of the video works become only a secondary aspect in the experience of the exhibition? Is it to be crossed off of the to-do-list used in the process of sightseeing? Are they even part of the exhibition? (Because they really are good, insightful, and challenging works of art.) If, yes, then due to the excessive duration of the works, the videos that won’t be watched will simply remain lists of titles in the catalogue. Relying on the off-chance that someone might watch them all shouldn’t be the reason for including so many works. Or maybe viewers should be encouraged to stop and actually take the time to experience the works. The real problem with this exhibition is that instead of traveling, which takes time and energy and planning, it was more like sight-seeing with a hop-on-hop-off bus that brings you to the most important places or stops for a few short minutes – just long enough to take a photo – and then moves on to the next “important place”, with little time or opportunity for the traveler/viewer to understand and immerse oneself.

Review: “The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in the New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” at Kumu

21/10/2017

The exhibition “The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in the New Art from Central and Eastern Europe”, curated by Magdalena Moskalewicz, is currently going on in the 5th-floor exhibition space at Kumu through 28 January 2018. This exhibition presents a wide range of contemporary artists from Eastern and Central Europe as it deals with a subject that is important in the context of recent history in the post-socialist and post-Soviet parts of Europe.

Already the title of the exhibition introduces the subjects that will be dealt with in the exhibition, as well as the time frame – from the fall of the Iron Curtain to the present day. The exhibition’s concept gives the artists the opportunity to reflect on the subject from both personal experience and the political reasons for traveling, non-traveling, or migration. This exhibition, with such a title and subjects, seems interesting from several points. One of the first to come to mind is the ever-present question of migration and immigrants entering Europe from East and North Africa, and the media-built hysteria and the political inability to do something to resolve the situation. This idea is also expressed in the exhibition’s accompanying text: “Europe’s response to foreign refugees shows that our participation in the global exchange was, and is, predominantly one-way. We do not willingly share the privileges that we gained after the fall of the Berlin Wall and as a consequence of our EU accession. We are enthusiastic about going abroad, but far less so about welcoming foreigners.”[1] Secondly, the exhibition seems to take control over the outdated idea of Eastern European art by specifically not showing it as peripheral art in contrast to Western art, but rather as an equal entity. By combining historical events with social contemporary issues, the exhibition and the curator have taken a very confident step towards changing already existing stigmatic thoughts about art in this part of the world. This approach could also be seen as a dialogue between East and West that discusses the historical reasons behind traveling and non-traveling experiences in the post-socialist and post-soviet countries. At first glance, this exhibition seems to both represent thorough research into the subject and present a wide range of contemporary artists, yet upon further study, there are some things that don’t seem completely thought through.

One of the best parts of the exhibition are the artworks. Twenty-four artists present twenty-seven artworks dealing with the subject of traveling or migration. The twenty-seven works have been divided into seven parts, or chapters, which was occasionally evident in the positioning of the artworks in the space; however, in most cases, this division can only be understood by reading the exhibition booklet. Even though the usual practice is to group artworks under similar subjects, the exhibition booklet doesn’t give reasons for the category titles or why specific works have been grouped into a certain category: The Politics Versus Politics of Travel, Global Circulation, Dreams of Space, Between East and West: Artistic Peregrinations, Postcolonial and Postsocialist Exchanges, Nationalism and Exile, Figure of Migrant. These titles give a narrative and context in which to see the works. From one point of view, it is understandable to point out the different ways of seeing migration or traveling and the differences in experience; however, if the viewer doesn’t have the booklet, it is impossible to keep track of the differences between these supposedly important contexts.

If all of the above-mentioned issues could somehow be explained away as not being truly problematic, there would, for me, still be one major, unsolvable issue left: how much time should one spend at the exhibition? Is the exhibition meant to be quickly consumed with a passing glance? Or is the exact opposite true? These were the questions I thought about after several shorter visits to the exhibition. However, knowing that this exhibition consists of many long video works, I wanted to see them all, from beginning to end. I calculated that this would take me four and a half hours; but after five hours, I still hadn’t managed to see all of the works. Every video work in the exhibition has its qualities, therefore, it is basically necessary to watch each one from beginning to end. Some are only seven to ten minutes long, but others go from half an hour to a maximum of 82 minutes. In total, the exhibition has nine video works as well as Karel Kopliment’s installation “Case No 13. Waiting for the Ship of Empties” (2017), which also contains a video recording of a performance that takes some time to watch. My calculation of four and a half hours was based only on the lengths of the videos as stated in the booklet; my estimate didn’t include looking at any of the non-video artworks at the exhibition.

Olga Chernysheva, Briefly. 2013, Drawing series, charcoal on paper, 37 × 59 cm each, Private collection of Irina and Maris Vitols, Riga, Latvia

In this large-scale exhibition, among the relatively large amount of worksthere are some that stand out more than others. For example, upon entering the exhibition space, one of the first things that the viewer is drawn to is Olga Chernysheva’s work “The Train” (2003). The artist has filmed the process of going through train cars, from one carriage to the next. The video is accompanied by a soundtrack featuring Mozart’s Andante, Concerto for piano and Orchestra No. 21 in C Major, which creates a very poetical atmosphere. Even though the author of the booklet points out that: “Made more than a decade after the collapse of the Soviet Union, this poetic and, at times, surreal film disturbingly evokes the hopelessness of the era”, I certainly didn’t feel that as I watched the work. This work did not disturb me nor did it instill a sense of hopelessness. The work might very well just depict reality, and the opinion stated in the description seems to be subjectively reflecting a Eurocentric world perception rather than the actual meaning of the work, i.e., everything needs to be shiny and new. Compared to the other works, this one was short and easy to immerse oneself in.

Vesna Pavlović, Fototeka. 2013/2016, From Fabrics of Socialism series, photographic installation, Courtesy of the artist

The other works, however, took more time to get into, such as Vesna Pavlovic’s work “Fototeka” (2013/2016). It is a photographic installation in which the artist projects onto a big gray curtain eighty archival photographs documenting the foreign travels of the Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito. The photographs change from tourist snapshots of architecture to photos of propagandist celebrations by the regime. The gray-colored curtain was apparently inspired by the stage design of official communist events, as well as serving as a reference to the Iron Curtain. It is interesting that one can’t see the photographs clearly on the curtain because the curtain itself has been lit with stage lighting. The problem with this work is that the slide projector changes the images so slowly that you see ten photographs in five minutes; once again, one needs to patiently watch the work for 40 minutes to see it all. No chairs are provided for those who wish to calmly watch the slide show, and there is nothing to indicate that one should actually do so.

Adrian Paci’s video “The Column” (2013), under the chapter Global Circulation, had a similar effect on me. The work surprised me both conceptually and visually, but it took time to watch the 26-minute long video from beginning to end in order to understand the quality and value of the work. Not only are the conceptual aspects of the work interesting, but also the execution of the video has been thoroughly thought through. The video depicts the creation of a column by highly-skilled Chinese workers on a ship. The idea is explained in the booklet so: “The classical column, based on the models of ancient Rome, was executed in quality marble by highly-skilled Chinese workers, thus complicating the common perception that goods ‘made in China’ are merely cheap fakes.” [2] Much like Chernysheva’s work, this piece can be watched again and again in a loop – it is simply mesmerizing. However, as it takes time to watch the video, most people will spend only a few minutes watching it before they leave the room. Maybe the “made in China” idea of quick and cheap consumption fits in here, too, in the sense that it doesn’t really matter whether or not the viewer watches the work from beginning to end. The question is, are we able to watch works from beginning to end?

Karel Koplimet’s two works, “Case No 11. TALSINKI” (2016) and “Case No 13. Waiting for the Ship of Empties” (2017), are compelling both visually and conceptually. Both case studies, even though not exhibited together, are connected to each other. The first one consists of two video projections of people coming off a ferry. The artist looks into the phenomenon of many Estonians going to Finland to work mostly low-skilled jobs, whereas Finnish tourists travel to Estonia to consume and transport cheap alcohol. Not only does he look at the idea of Estonians going to Finland to work and Finns coming to Tallinn to party, but by using the case-study style, he expresses a certain seriousness in his approach to the documentation. This is especially apparent when we look at the raft which, at first, doesn’t seem connected to anything because it has been placed in the atrium and not on the 5th floor with the rest of the exhibition. The dedication of the artist is impressive – not only to talk about or present a conceptual idea, but to also create a raft from beer cans gathered in Finland, and then actually travel with it back to Tallinn.

C.T. Jasper & Joanna Malinowska, Halka/Haiti 18°48’05″N 72°23’01″W. 2015, Multichannel video projection, 82 min, Collection of Zachęta—National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, Project curated by Magdalena Moskalewicz for the Polish Pavilion at the 56th International Art Exhibition—la Biennale di Venezia

After going through the many rooms of the exhibition, the penultimate one contains C.T. Jasper & Joanna Malinowska’s “Halka/ Haiti 18°48'05''N 72°23'01''W” (2015). The interesting part of the work is its special placement and 180° video projection of an old Polish opera played to Haitian villagers on the street in the mountain village of Cazale in Haiti. In a way, this work is surreal because of both the environment in which it takes place and the intrinsic concept of the work. The work wasn’t created for the exhibition since it had already been exhibited at the 56th Venice Biennale at the Polish National Pavilion. Altogether the video work, which is more like a feature film in terms of length, takes an hour and a half to watch. Even though there were comfortable chairs to sit in and enjoy the work, by the time the viewer reaches this point in the exhibition it is quite difficult to watch from beginning to end. Are we really meant to watch it, or does the exhibition expect a quick hit-and-run attitude towards video art? The work is also accompanied by a half-hour documentary on the preparation for the opera and interviews with the artists’ Haitian collaborators and audience. Again, as much it would be interesting to see the documentary, is it meant to be seen?

Lastly, the final room of the exhibition, which at first glance looks like one installation and is divided betweentwo different titles – “Nationalism and Exile” and “Figure of a Migrant” – is, in fact, four unrelated works combined together in one small space. Even after reading the concepts of each work, the issue is that some of the works literally overshadow the others. Which means that putting so many works together in such a small space doesn’t seem right. The final room consisted of Alban Muja’s “My Name, Their City”, Roman Ondák’s “Casting Antinomads”, Dushko Petrovich’s “El Oso Carnal”, and Daniel Baker’s “Copse”. At firstI thought it was one installation that could be seen as one artist reflecting on the subject through different media. However, only upon subsequent visits to the exhibition did I understand that there were, in fact, three artists presenting there. And now, as I am writing this review and going through the booklet, I understand that there were actually four artists presenting their works in that one space. The space is so small that the works disappear and lose any meaning they may have had on their own. Of course, this would be fine if the works were initially meant to be cramped together and overlapping each other, with the specific intent of making the viewer perplexed and confused.

My issue with the exhibition is that by putting so many artworks together, it enforces quick consumption. You won’t have time to actually look into it at all. You won’t be able to experience all the works. You read about something, assume what it will be about, and then continue on. There is too much information being presented, and one can become tired even after seeing only half of the exhibition. If the goal of the exhibition is to watch all of the works (if the works are, indeed, meant to be watched at all), then the space and environment don’t support this. The chairs, or even sometimes the lack of chairs, don’t allow people to sit down and really enjoy the works for the full time that each one requires.

Has the watching of the video works become only a secondary aspect in the experience of the exhibition? Is it to be crossed off of the to-do-list used in the process of sightseeing? Are they even part of the exhibition? (Because they really are good, insightful, and challenging works of art.) If, yes, then due to the excessive duration of the works, the videos that won’t be watched will simply remain lists of titles in the catalogue. Relying on the off-chance that someone might watch them all shouldn’t be the reason for including so many works. Or maybe viewers should be encouraged to stop and actually take the time to experience the works. The real problem with this exhibition is that instead of traveling, which takes time and energy and planning, it was more like sight-seeing with a hop-on-hop-off bus that brings you to the most important places or stops for a few short minutes – just long enough to take a photo – and then moves on to the next “important place”, with little time or opportunity for the traveler/viewer to understand and immerse oneself.