The brightest man in the orchestra

Kaarel Kurismaa and his Yellow Light Orchestra

26/11/2018

Pink, orange, blue, red. And yellow, of course. These bright, vibrant, lively colours characterise the oeuvre of Kaarel Kurismaa, one of the most important Baltic artists of the second half of the 20th century. He is the pioneer of Estonian kinetic and sound art and the creator of various monumental sculptures and stained-glass windows for public buildings. But above all he is a very pleasant person who doesn’t like to be called a revolutionary.

Kurismaa’s retrospective exhibition Yellow Light Orchestra is currently on view at KUMU in Tallinn until February 23, 2019. It not only gives a broad insight into Kurismaa’s creative growth but also provides a new perspective on 20th-century Estonian art. As we already know, art in eastern Europe during that period was strictly controlled by the government, and more unusual, eye-catching escapades were not acceptable. However, Kurismaa’s creations are more than just “eye-catching”. His pieces, mostly made in the 1970s and 80s, are conceptually radiant and somehow provocative. Although he admits that back in the Soviet era it was much harder to justify making this kind of art, and he was often rejected from participating in exhibitions, his art seems to prove the opposite. Strolling through his Yellow Light Orchestra seems almost like floating in a nirvana where the past meets the present. A thought wanders into my mind: Can the power of a personality overcome the power of an ideology?

Kurismaa was born in 1939 in Pärnu into a family of confectioners. Since early childhood, he was inspired by his family’s trade. The delicate approach to preparation, the combinations of different elements, and the delight that was gained from the work strongly influenced the young artist and is still reflected in his artwork today. Some of his pieces actually call to mind a luscious whipped-cream cake or a sweet piece of candy wrapped in a shiny paper.

Kurismaa tells me that his uncle (also a confectioner) had a great impact on him: “My uncle was quite successful at what he did. But when the Soviet times began, he didn’t want to work at all – he was part of the bourgeois society. Confectioners work with various essences, and so he began making some compositions of aromas. When I was a small boy, my uncle always took me to cafés and told me about the possibility of variegating things. I guess this was when I got the idea of combining things and media.”

At the age of 15 Kurismaa made an important life decision. He left school and went to work in a metal factory, where he was amazed by the machines. Movement and sound has inspired him ever since.

Later on, Kurismaa studied at the Tartu Art School and in the Department of Monumental Painting at the State Art Institute. After graduating from art school in 1965, he began working as an artist-decorator for Kaubamaja (Tallinn Department Store). There he quickly gained popularity as an outstanding window-dresser, and his new designs were always received with the same delight as a theatre spectacle.

In the catalogue for the present exhibition (which, by the way, is Kurismaa’s first catalogue ever), curator Ragne Soosalu writes that the department store was an ideological opportunity to make-believe at improvements in the quality of life. This notion also became one of the turning points of Kurismaa’s artistic attitude: “A creative position at the front of the consumer sector provided the young artist with an ideologically playful outlet. Such placement between two worlds became characteristic of the majority of his works and gave him confidence to step over various boundaries established in the Estonian art world.”

Kurismaa began participating in exhibitions in the late 1960s, which was a difficult time for upcoming and ambitious Soviet artists. Despite the unrewarding environment, the government was not against the young artist’s abstract sculptures and monumental mural paintings, because they were classified as decorative: “At the same time, they didn’t accept other kinds of my art. It was a strange situation for me, because some things were accepted despite the fact that I was considered too modern. I like the absurd and the idea of modernity. Also, I can’t take things too seriously, and I hate academic opinions. I’ve always used unusual colours and have loved to put yellow, violet and orange together. We wanted to keep the same idea here, in this exhibition.”

With the help of art, Kurismaa began interpreting everyday life from ironic aspects. He is a master of ready-made objects, combined from surrounding things or commonly used items. The oldest piece on view in the exhibition is Monument of Love, which includes parts of dolls produced in the 1950s. Because these were the only type of doll available in the Soviet Union, their specific form and figure has become something very recognisable and could even be labelled as “classic”. However, Kurismaa has taken a different approach and transformed the dolls into baroque angels, thus giving them a different meaning and a visual connotation.

Another piece included in the exhibition is A Light Object (1975), an object with rhythmically pulsating light within a plastic case. “This piece is made from simple helmets that are usually worn to protect your head,” says Kurismaa. “I found them thanks to some of my friends. I’ve always had access to a variety of materials, especially when I worked as a production designer at Tallinnfilm animation studios and puppet animation studios. I had so many materials available and could just take them. It was the same when I worked at the department store.”

The origins of kinetic art as we know it can be dated to 1955, when the group exhibition Le Mouvement was held at the Galerie Denise René in Paris. It was then that Victor Vasarely published his Yellow Manifesto, also known as the manifesto of kinetic art. But it is obvious that traces of kineticism in art are to be found ever since Marcel Duchamp created his Bicycle Wheel in 1913.

For Kurismaa, kinetic art is associated with mechanical movement. The visual effect is just as important, of course, but electronically attained interactions have interested him since the beginning of his career. The most interesting thing is that Kurismaa has always refused to derive inspiration from Western art traditions, faithfully finding encouragement and motivation in his own surroundings: “Because of the dark and unpleasing Soviet reality, I tried to create this crazy, slightly metaphysical feeling. Some kind of fantastical world out of this matter.”

Furthermore, this dark Soviet reality stimulated Kurismaa to create intense and complex public objects. By the end of the 1970s, he was receiving numerous commissions to make monumental sculptures for public spaces, such as the High-Voltage Networks of the North Region, Tallinn’s central post office and the Neptun Hotel. Unfortunately, most of these objects no longer existed by the beginning of the 21st century. “The object for the High-Voltage Networks was such a beautiful and valuable sculpture, it was perfect for the industrial suburb,” states Kurismaa. “But it was just destroyed about ten years ago. The same is true of the kinetic sound object for the Tallinn Postal Building. The house itself was built in 1980, when the Olympic Games were organised. Just a few years ago, the historical building was renovated as a shopping centre. When the object was destroyed, they even wanted to give me back some parts of it. Unbelievable, isn’t it? Almost as if people here couldn’t understand the meaning of art.”

Kurismaa has always stood out as one of the most interesting and important Estonian artists of the 20th century. To answer my question above, about whether the power of a personality can overcome the power of an ideology, it seems that quite a few artists have tried to prove this, but only some have succeeded. Kurismaa, undoubtedly, is one who has succeeded.

Kaarel Kurismaa and his Yellow Light Orchestra

Auguste Petre

26/11/2018

Pink, orange, blue, red. And yellow, of course. These bright, vibrant, lively colours characterise the oeuvre of Kaarel Kurismaa, one of the most important Baltic artists of the second half of the 20th century. He is the pioneer of Estonian kinetic and sound art and the creator of various monumental sculptures and stained-glass windows for public buildings. But above all he is a very pleasant person who doesn’t like to be called a revolutionary.

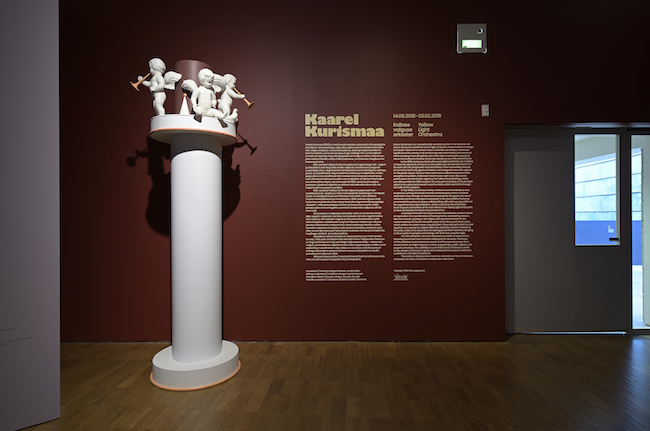

Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

Kurismaa’s retrospective exhibition Yellow Light Orchestra is currently on view at KUMU in Tallinn until February 23, 2019. It not only gives a broad insight into Kurismaa’s creative growth but also provides a new perspective on 20th-century Estonian art. As we already know, art in eastern Europe during that period was strictly controlled by the government, and more unusual, eye-catching escapades were not acceptable. However, Kurismaa’s creations are more than just “eye-catching”. His pieces, mostly made in the 1970s and 80s, are conceptually radiant and somehow provocative. Although he admits that back in the Soviet era it was much harder to justify making this kind of art, and he was often rejected from participating in exhibitions, his art seems to prove the opposite. Strolling through his Yellow Light Orchestra seems almost like floating in a nirvana where the past meets the present. A thought wanders into my mind: Can the power of a personality overcome the power of an ideology?

Kaarel Kurismaa, 1966

Kurismaa was born in 1939 in Pärnu into a family of confectioners. Since early childhood, he was inspired by his family’s trade. The delicate approach to preparation, the combinations of different elements, and the delight that was gained from the work strongly influenced the young artist and is still reflected in his artwork today. Some of his pieces actually call to mind a luscious whipped-cream cake or a sweet piece of candy wrapped in a shiny paper.

Kurismaa tells me that his uncle (also a confectioner) had a great impact on him: “My uncle was quite successful at what he did. But when the Soviet times began, he didn’t want to work at all – he was part of the bourgeois society. Confectioners work with various essences, and so he began making some compositions of aromas. When I was a small boy, my uncle always took me to cafés and told me about the possibility of variegating things. I guess this was when I got the idea of combining things and media.”

Kaarel Kurismaa, 1984. Photo: Gunnar Laanela

At the age of 15 Kurismaa made an important life decision. He left school and went to work in a metal factory, where he was amazed by the machines. Movement and sound has inspired him ever since.

Later on, Kurismaa studied at the Tartu Art School and in the Department of Monumental Painting at the State Art Institute. After graduating from art school in 1965, he began working as an artist-decorator for Kaubamaja (Tallinn Department Store). There he quickly gained popularity as an outstanding window-dresser, and his new designs were always received with the same delight as a theatre spectacle.

Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

In the catalogue for the present exhibition (which, by the way, is Kurismaa’s first catalogue ever), curator Ragne Soosalu writes that the department store was an ideological opportunity to make-believe at improvements in the quality of life. This notion also became one of the turning points of Kurismaa’s artistic attitude: “A creative position at the front of the consumer sector provided the young artist with an ideologically playful outlet. Such placement between two worlds became characteristic of the majority of his works and gave him confidence to step over various boundaries established in the Estonian art world.”

Kurismaa began participating in exhibitions in the late 1960s, which was a difficult time for upcoming and ambitious Soviet artists. Despite the unrewarding environment, the government was not against the young artist’s abstract sculptures and monumental mural paintings, because they were classified as decorative: “At the same time, they didn’t accept other kinds of my art. It was a strange situation for me, because some things were accepted despite the fact that I was considered too modern. I like the absurd and the idea of modernity. Also, I can’t take things too seriously, and I hate academic opinions. I’ve always used unusual colours and have loved to put yellow, violet and orange together. We wanted to keep the same idea here, in this exhibition.”

Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

With the help of art, Kurismaa began interpreting everyday life from ironic aspects. He is a master of ready-made objects, combined from surrounding things or commonly used items. The oldest piece on view in the exhibition is Monument of Love, which includes parts of dolls produced in the 1950s. Because these were the only type of doll available in the Soviet Union, their specific form and figure has become something very recognisable and could even be labelled as “classic”. However, Kurismaa has taken a different approach and transformed the dolls into baroque angels, thus giving them a different meaning and a visual connotation.

Another piece included in the exhibition is A Light Object (1975), an object with rhythmically pulsating light within a plastic case. “This piece is made from simple helmets that are usually worn to protect your head,” says Kurismaa. “I found them thanks to some of my friends. I’ve always had access to a variety of materials, especially when I worked as a production designer at Tallinnfilm animation studios and puppet animation studios. I had so many materials available and could just take them. It was the same when I worked at the department store.”

Kaarel Kurismaa. P2kapiku altar, 1973. Erakogu

The origins of kinetic art as we know it can be dated to 1955, when the group exhibition Le Mouvementwas held at the Galerie Denise René in Paris. It was then that Victor Vasarely published his Yellow Manifesto, also known as the manifesto of kinetic art. But it is obvious that traces of kineticism in art are to be found ever since Marcel Duchamp created his Bicycle Wheel in 1913.

For Kurismaa, kinetic art is associated with mechanical movement. The visual effect is just as important, of course, but electronically attained interactions have interested him since the beginning of his career. The most interesting thing is that Kurismaa has always refused to derive inspiration from Western art traditions, faithfully finding encouragement and motivation in his own surroundings: “Because of the dark and unpleasing Soviet reality, I tried to create this crazy, slightly metaphysical feeling. Some kind of fantastical world out of this matter.”

Kaarel Kurismaa. 1975

Furthermore, this dark Soviet reality stimulated Kurismaa to create intense and complex public objects. By the end of the 1970s, he was receiving numerous commissions to make monumental sculptures for public spaces, such as the High-Voltage Networks of the North Region, Tallinn’s central post office and the Neptun Hotel. Unfortunately, most of these objects no longer existed by the beginning of the 21stcentury. “The object for the High-Voltage Networks was such a beautiful and valuable sculpture, it was perfect for the industrial suburb,” states Kurismaa. “But it was just destroyed about ten years ago. The same is true of the kinetic sound object for the Tallinn Postal Building. The house itself was built in 1980, when the Olympic Games were organised. Just a few years ago, the historical building was renovated as a shopping centre. When the object was destroyed, they even wanted to give me back some parts of it. Unbelievable, isn’t it? Almost as if people here couldn’t understand the meaning of art.”

Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

Kurismaa has always stood out as one of the most interesting and important Estonian artists of the 20thcentury. To answer my question above, about whether the power of a personality can overcome the power of an ideology, it seems that quite a few artists have tried to prove this, but only some have succeeded. Kurismaa, undoubtedly, is one who has succeeded.