The Urge to Belong

Contemporary art from Sweden at Tartu Tartmus Art Museum

15/03/2019

I believe that the frequent exhibition visitor (let us call him – F. V.) chooses what cultural events to see similarly to how he makes other life decisions. It means that, firstly and most importantly, F. V. makes his monthly, weekly or daily exhibition plans based on his individual interests and taste. If F. V. is passionate about contemporary art, it is unlikely that he would visit a retrospective of a local old master. If he is interested in politics and social art, it is more credible that F. V. would go to a curator-created exhibition that contextualises the modern culture and the ambient. But if said ‘frequent visitor’ is fascinated by art because, to his mind, it is the greatest source of beauty, he would probably visit a more classical or traditional type of exhibition. By saying all this, I would like to imply that there exist certain categories according to which we form our daily lives, from our day-to-day work plans to tours of museums, galleries, exhibition halls and other culture spaces. These categories are often based on their content or, to be more precise, on their perceived content, and only sometimes do the structure or concept of an exhibition coincide with the visitor’s aesthetic sense. For example, the subtitle of the exhibition ‘Stories of Belonging’, on view at the Tartmus Art Museum of Tartu through 5 May, says: Contemporary Art of Sweden, thus, it could seem like a perfect destination for an F. V. who is a current Nordic art lover and reads only exhibition titles before actually visiting them. Once again – the momentary perception proves itself by letting us think that this exhibition of contemporary art could be so easily associated with something, in this case, the cultural scene of Sweden. In reality, this subtitle includes far more than merely a reference to a ‘supposed’ affiliation or the nationality of artists represented at the exhibition. Dana Sederowsky, Tova Mozard, Meriç Algün, Sirous Namazi, Santiago Mostyn, Annika Eriksson, Sahar Al-Khateeb and Meira Ahmemulic are active Swedish artists who use art as an unconditional language for expressing their emotions and personal experiences, focusing on the situation of minorities. This time the subtitle of ‘Stories of Belonging’ is a play on social factors and the perception depths of the F. V.

Stories of Belonging. Exhibition view with a photo by Tova Mozard and an installation by Sahar Al-Khateeb

.jpg)

Tova Mozard. A selection of photos from 2003-2016.

Tova Mozard. A selection of photos from 2003-2016

‘Stories of Belonging’, curated by Joanna Hoffmann and Hanna-Liis Kont, is not the first look at the topical events and concepts of Estonia’s neighbouring countries taken by the Tartu Museum. For some time now Tartmus has been showing series of exhibitions dedicated to art from Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, therefore expanding their visitors’ horizons and introducing the museum to the international art scene. In 2015 Tartmus showed a selection of works by contemporary Polish artists – ‘My Poland. On Recalling and Forgetting’ (curated by Rael Artel); ‘Aesthetics of Repair in Contemporary Georgia’ (curated by Marika Agu), accordingly showing contemporary art from Georgia, followed in 2016. Two years ago, in the spring of 2017, curator Julia Polujanenkova brought to Tartu works by seven young Russian artists in an exhibition entitled ‘Inconvenient Questions. Contemporary Art from Russia’. Each of these exhibitions, in some way, has underlined the existence of taboos in the contemporary world, as well as brought to attention social topics that are often discussed in modern art. ‘Stories of Belonging’ has been created by following a similar formula – the main focus of the exhibition is exploration of the Swedish society and questions of equality in the 21st century: ‘The country has had a very open immigration and has accepted a large number of refugees in the recent past. Despite this, people with foreign backgrounds or different ways of life have to daily face such problems as difficulties of adaptation, exclusion, discrimination etc. These problems are also important to many Swedish artists.’ If we return to the meaning of the subtitle, it becomes clearer that the idea behind it actually speaks upon the coexistence of people and not some [imaginary or real] differences on a national level.

As previously mentioned, the core of the exhibition lies in analytic interest in social realities; however, the main body of the display is composed of artworks by eight artists from different generations and backgrounds. The story opens with a glass and lamp installation ‘Chandelier’ (2014) by Iranian-Swedish artist Sirous Namazi. At first, the glass object attracts for simple associative reasons; the orange/pinkish classically shaped chandelier with six light bulbs reminds of a relic that could be found in a lot of houses around the mid-1900s. And it is quite obvious why – Namazi (who fled to Sweden in 1986 as a religious refugee) has been working on a sculptural series ‘Twelve Thirty’ since 2014, reconstructing some of the items that, along his family home, were destroyed during the Bahá’i persecutions in 1979. This illuminating ‘Chandelier’ has been reconstructed based on Namazi and his family member’s memories of their home and some photos that have survived. Looking back at that time and searching for evidence from his previous home [and life], Sirous Namazi has somehow overcome his fears and turned his remembrances into art.

.%20Video.jpg)

Meira Ahmemulic. Something Good Needs to Happen (2017). Video.

.%20Video%20(music%20by%20Slow%20Wave).jpg)

Santiago Mostyn, Delay (2014). Video (music by Slow Wave)

It’s interesting to watch the video work ‘Delay’ (2014) by Santiago Mostyn where he imitates and approaches Scandinavian-looking young men on the streets of Stockholm, the short film ‘Something Good Needs to Happen’ (2017) by Meira Ahmemulic, as well as to delve into the photos made by the film director and artist Tova Mozard. Seems that Joseph Kosuth’s fascination with the art of chairs, in some way, has been inherited by the lesser known artist Sahar Al-Khateeb. His site-specific installation, accompanied by found objects, revives the importance of simplicity in today’s context. Although the status of the objects or things used in this installation has long been gone, they have earned another, different kind of beauty – the idea behind Al-Khateeb’s work can also be extended to the coexistence of various social groups in today’s society.

,%20Video%20(2).jpg)

Annika Eriksson. I Am the Dog that was always here (2013). Video.

,%20Video%20(3).jpg)

Annika Eriksson. I Am the Dog that was always here (2013). Video.

,%20Video.jpg)

Annika Eriksson. I Am the Dog that was always here (2013). Video.

Presumably the most well-known artist represented at this exhibition is Annika Eriksson with her video work ‘I Am the Dog That Was Always Here (Loop)’ (2013). The 7-minute film follows the life of stray dogs who live in packs on the outskirts of Istanbul. The artist impersonates the dogs for the purposes of research on gentrification processes and deepens the metaphorical effect by complementing the image with a text in Turkish. Is it one of the dogs speaking or is it the dog that we all know so well? The one that has always been here? These are the questions that could be asked while watching the video. It seems that, in a way, Eriksson has managed not only to capture the daily life of such important animals in the society of today but also, metaphorically speaking, reopen an old wound that has to do with a much deeper problem – those who fail to embrace urbanization get expelled to the outskirts. ‘I Am the Dog That Was Always Here (Loop)’, just as its title says, is played in a loop, thus becoming a never-ending story and preparing ground for a stream of consciousness.

.%20Section%20VIII_%20Tartu%20Public%20Library%20(3).jpg)

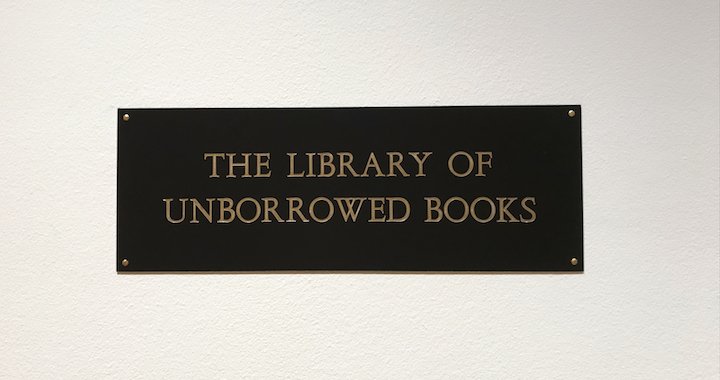

Meriç Algün. The Library of Unborrowed Books (2012-). Section VIII. Tartu Public Library

.%20Section%20VIII_%20Tartu%20Public%20Library.jpg)

Meriç Algün. The Library of Unborrowed Books (2012-). Section VIII. Tartu Public Library

Another quite intriguing work is ‘The Library of Unborrowed Books. Section VIII: Tartu Public Library’ by the Turkish-born artist Meriç Algün. The project, launched in 2012 and still going on, is based on the meaning of books and reading, as well as the concept of library as an institution that is a manifestation of knowledge. Over eight years, Algün has made site-specific sections in collaboration with libraries in Stockholm, New York, Sydney, Athens and other places around the world. ‘The Library of Unborrowed Books’ seems like a challenging and a sad place at once. On the one hand, the respective selection of books shows the preservation of tradition and cyclicality of interests. On the other hand, this installation represents a selection of books that have actually never been borrowed from the represented city’s library. If we accept that the main function of a library is the act of lending books (and the need to do so), the fact that these specific books have never been wanted by anyone marks them as lonely. The artist herself writes that this installation is a library of books that have not been discovered yet – thus, underlining the power of art as an instigator of important stories.

A somewhat less inspiring artwork featured at the exhibition is a video chapter ‘The Exit’ (2016) from the ‘Special Announcements’ series by Dana Sederowsky. The artist (or the character created by her) confusingly and continuously asks where the exit is, suggesting that it is not really about a physical exit or a door but rather an emotional failure to belong to her own location. Although the artist has been working on the video project since 2006 and has developed it into a performative diary, it just somehow didn’t seem to work with the other artworksin the context of ‘Stories of Belonging’ (and the whole concept of the exhibition) that strives to draw attention to problems that have not been named yet.

Stories of Belonging. Exhibition view with an installation by Sirous Namazi

As mentioned before, ‘Stories of Belonging’ is a compilation of contemporary art by experienced artists for visitors with a thirst for knowledge. It might not be an exhibition to ‘take your breath away’; however, it is an interesting insight into Scandinavian social art and eight different, inimitable interpretations of the present-perfect.