Kiki Smith’s homage to the island of Hydra

28/06/2019

The DESTE project space on the Greek island of Hydra is noteworthy not only for of its location in a former slaughterhouse (hence its name ‘Slaughterhouse’) but also for its tradition of hosting only one exhibition a year, each created specially for this space by one artist or group of artists. American artist Kiki Smith’s exhibition Memory is already the eleventh such art event in the history of the DESTE Project Space Slaughterhouse. It opened during the full moon on June 17, and that is unlikely to have been a coincidence.

Kiki Smith: Memory. DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra (June 18–Sept. 30, 2019). Photo: Arterritory

Memory is Smith’s offering to Hydra and the Greek sea, and it was born in a location where sacrifices once took place. Unfortunately not to the gods but to the insatiability of Homo sapiens, in the form of raising and slaughtering animals for human consumption. The most selfish type of this “sacrifice” – a greed with the ferociousness of a multiheaded serpent – currently threatens to destroy the “sacrificers” themselves by imperiling the survival of the planet as a whole. Smith’s work is about roots: the lost link/bridge between people and nature, spiritualism and rationality, indigenous cultures and the relentless materialism of the West, mythology and urban reality, life and death. It is an homage to Hydra the island as well as Hydra the sea serpent and largest constellation in the southern sky, whose tail lies between Centaurus and Libra. This constellation was first catalogued by Greek astronomer Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD. Despite its size of 1303 square degrees, it contains only one bright star, Alphard, whose name means ‘the solitary one’.

An ancient myth tells that the Greek god Apollo once asked a crow to bring him some water. Long ago, crows are said to have been silvery white and have a beautiful song. The crow diligently accepted the task, but along the way it came across a fig tree full of fruit. The fruit was not yet ripe, so the crow decided to wait a little bit. When the figs had finally ripened, the crow enjoyed a grand meal (which turned out to be its last meal). Its stomach full, the crow suddenly remembered its task, quickly filled the cup with water and hurried back to Apollo, making excuses that the water serpent had prevented it from getting near the water sooner. Apollo was young but not easily fooled, and he punished the crow for its selfishness by turning its feathers black and its voice into an unpleasant caw. He then threw the crow and the cup up into the sky, onto the back of the water serpent, warning the serpent to make sure the crow is never again able to reach the cup and thus quench its thirst.

Kiki Smith: Memory. DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra (June 18–Sept. 30, 2019). Photo: Arterritory

Smith’s work is inhabited by all of the mythological characters and instruments of Hydra: the crow (Corvus), the owl (Noctua), the cup or chalice (Crater), the sextant (Sextans) and the cat (Felis). On the roof of the former slaughterhouse, for its part, sits Capricorn, or the sea goat – a creature with a goat’s head and a fish’s tail fluttering in the wind, which, if one is to believe the story, allows it to travel between both worlds, between the heavens and the depths of the sea, and stopping here on land as it moves from one extreme to the other. Diving into the deepest wells of the imagination, uniting creativity with productivity.

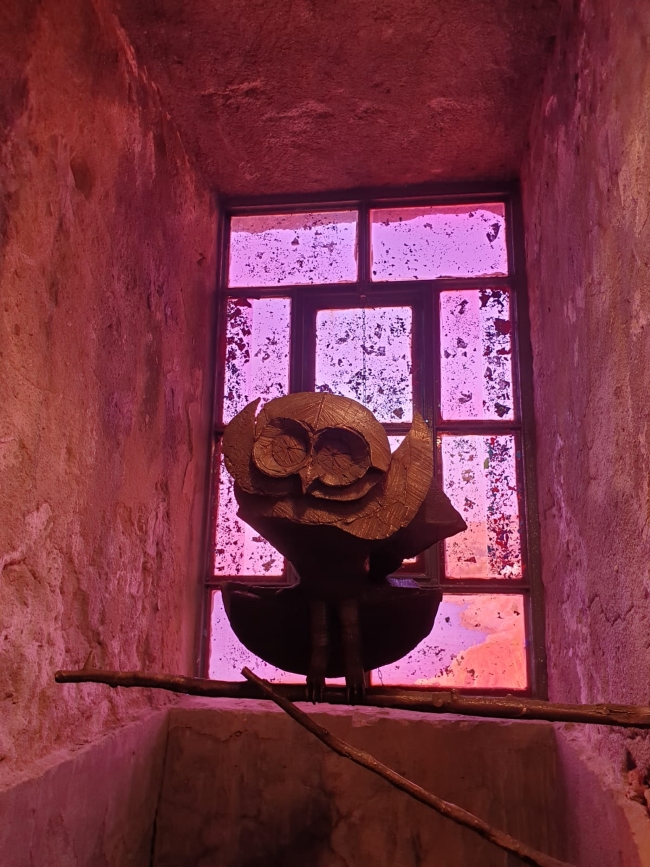

In the former slaughterhouse itself, where goats once awaited their deaths, now lives a golden mermaid bathed in reddish light. Her knotted fish’s tail coils through the bars – to freedom. She is guarded by a black cat on the windowsill, which at first glance is almost unnoticeable. The air is saturated with the aroma of sage incense, used in rituals since antiquity, including in ancient Egypt and Rome, to energise and cleanse spaces and their inhabitants. Sage is also said to improve the memory and thought processes. In place of a blood-filled sacrificial vessel, a container of water stands in the middle of the slaughterhouse, reflecting the walls and barred windows as well as the magically rose-coloured light. Harshness and poetry. A cat hides in one corner of the space. An owl sits in the window. Two sculptures on a pedestal bring to mind the world fused into an tangled ball of yarn uniting animals and people. Creatures of the sea, the land and the sky. But they could just as well be the two hemispheres of the brain. Or perhaps the home of the mind? The intellect of the realms of plants, animals and humans. As Carl Jung once wrote, “It is as if our consciousness were a continent, an island or even a ship on the great sea of the unconscious.”

Kiki Smith: Memory. DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra (June 18–Sept. 30, 2019). Photo: Arterritory

Further, on the terrace of the small slaughterhouse, a golden-metallic “face” sparkles in the fading sunlight, its two eye holes providing views of the sky and sea. Water also holds memories, and the island itself was historically called Hydrea, from the Greek word Υδρέα (‘water’).

When asked how the idea for this work emerged, Smith says that it simply came to her when she arrived on the island. “I arrived here, and it all just fell into place. It popped into my mind. I follow where the work wants to go. I enter the space, and it tells me what to do.” Her voice has a gentleness to it, strong and fragile at the same time. Humbleness and wisdom. Perhaps it’s the magic of the full moon, but she seems to be both inside and outside – present but also a wise observer from a distance. She does not join the crowd of guests; instead, she stands to the side, nearer to the sea. Smith has long, silvery hair and a fragile, feminine bearing. Her blouse is decorated with a drawing of a mythological bird’s wing or sea serpent.

Kiki Smith: Memory. DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra (June 18–Sept. 30, 2019). © Kiki Smith; Photo: George Skordaras

“I was once on the Island of Bequia, in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, where they hunted whales from small boats and slaughtered goats. One day a goat’s entrails floated in the water as we swam and then washed up on the sand. I made photographs and drawings of the organs, which got me drawing again after several years of not doing so. Later that month, a hurricane came and wiped away two or three metres of the beach,” Smith writes in her artist statement. “(...) I made films of the East River in New York in 2005, of glints of light on the river. I made them into cyanotypes this year, and from those into flags to fly back at the sea on Hydra.”

Smith was born into an artistic family in 1954 in Nuremburg, Germany, but grew up in New Jersey. Her mother, Jane Lawrence, was an opera singer, and her father, Tony Smith, was a sculptor known for his monumental black-and-white sculptures that were even exhibited at the Venice Biennale. Her grandfather was an altar carver, and the family counted Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock among its friends. Already as a young child, Smith and her sisters helped their father in his studio, and around the age of twenty-four she decided to become a professional artist herself. She worked all sorts of unusual jobs, including as an electrician’s assistant, which, as she later concluded, “led me to consider life, art and the body anew”. Because our bodies are also electrically charged systems in which the positive and negative constantly intertwine and nothing is ever self-contained.

Kiki Smith: Memory. DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra (June 18–Sept. 30, 2019). Photo: Arterritory

Smith held her first solo show, Life Wants to Live, at The Kitchen in New York City in 1982. Her father died in 1980, and in 1988 her sister Beatrice died of AIDS. Her good friend and creative partner, the artist, photographer, and director David Wojnarowicz also died of AIDS in 1992. Smith’s 1988 exhibition at the Joe Fawbush Gallery, in which she displayed bottles of blood, urine, sperm and other fluids, served as a turning point in her career.

Smith later created a series of death masks dedicated to her family and friends. Her artwork lives in the border zone between the body and the spirit, life and death, culture and nature, and it is based on personal memories, history, social and political changes. She has always been interested in the metamorphoses of the body (especially the female body) and the physicality of the body. Worldliness and strength. She has created sculptures of stylised human body parts and internal organs. In her artwork, women are born from deer (Born, 2002) and are not afraid of holding a dead wolf’s paw (Rapture, 2001). In the 1980s, Smith’s art focused on the AIDS crisis, sexuality and the feminist discourse. In the 1990s she turned to legends, myths, fairytales and religious mythology. In addition to humans, her artistic space is inhabited by birds and animals (crows, cats, deer, snakes, wolves, eagles), which form a surreal symbiosis of the physical (bodily) and fantasy worlds in which everything is mutually linked: humans, nature and the universe. Smith’s husband is a beekeeper, and together they care for several hives of bees. In fact, nature is one of Smith’s main sources of inspiration.

Kiki Smith: Memory. DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra (June 18–Sept. 30, 2019). © Kiki Smith; Photo: George Skordaras

Often in her interviews Smith has said that she considers her work as a form of healing. First of all, as something healing for herself. When I ask her whether art has the power to change the world, she says: “I don’t think it’s within the power of one person to change the world. It’s with our thoughts that it’s possible. We have to become more conscious persons. Art is a great and beautiful language. Each of us has our own language – our own field in which we work – and by using this in a beautiful way, we can make the world a better place. Creativity is just the capacity of consciousness. It’s a kind of synthesis. It’s been a long road until I arrived at that.”

Although Smith is usually associated with sculpture, she has expressed herself just as vividly in drawing and printmaking as well as video art. “All things are different. Every material has its own potential. It has everything. It’s ready to go in any direction anybody wants to take it,” she says. Smith also works quite a bit with textiles, “because they’re beautiful”. Although she discovered it only later in life, one of her newest mediums is tapestry. “But this is just because I did not have any opportunity to do so earlier. You know, people mostly make things because of accessibility or opportunity. And somebody gave me the opportunity to make Jacquard tapestries, and this is how it started,” she explains. In 2010 she created twelve large-format tapestries, which were exhibited early this year in the What I Saw on the Road at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence. A retrospective of her work can be seen until September of this year at the Belvedere in Vienna.

When I asked Greek art collector, industrialist and philanthropist Dakis Joannou, who is the founder of the DESTE Foundation for Contemporary Art, what exactly motivated him to devote the DESTE project space to Kiki Smith this year (following David Shrigley last year), he responds succinctly, “An inner feeling.” His reaction when first seeing the exhibition: “Incredible. Way beyond what I expected. It’s a wonderful dedication to the island of Hydra.”

Kiki Smith: Memory. DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra (June 18–Sept. 30, 2019). Photo: Arterritory

The prominent guests at the opening of Smith’s exhibition ranged from photographer Martin Parr to artist Maurizio Cattelan and gallery owner Thaddaeus Ropac; among them was also art-scene superstar Jeff Koons. “I love Hydra. I’ve been coming here since 1985,” he says. When I ask Koons what first comes to mind when he hears the word ‘slaughterhouse’, he says, “Well, you know, you think about violence.” I comment that his work usually does not include any violence. “I think my work has a lot of feelings, sensations. I like the strong imagery. Sensibility,” he says.

It is precisely Koons’ work One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank – an orange basketball suspended in a tank of water – that is considered the official start of Joannou’s art collection. He bought it in 1985 for 2700 dollars at a gallery in New York. At the time, Koons was still far from the peak of his career, which he now enjoys dressed in a very simple white shirt and inconspicuously blending in with the crowd. Today, Joannou’s collection contains a work from each period of Koons’ career; the two men are friends, and Koons, having been inspired by a photograph of British military camouflage from the First World War, has painted the design on Joannou’s yacht, Guilty, which is moored in Hydra’s harbour. Will Koons be the next artist to receive an invitation to create a work of art, or dialogue, with the island of Hydra, its history and mythology? That was the intriguing question in the air at the recent exhibition opening at the Slaughterhouse. In any case, Hydra is full of mystery and still today able to turn its reality into mythology as masterfully as it did in the past.

Una Meistere in conversation with Kiki Smith at the opening of Kiki Smith’ s exhibition “Memory” at the DESTE Foundation Project Space on Hydra Island. Photo - Arterritory