Utopia, Korean-Style

Lee Bul, Utopia Saved. The Manege Central Exhibition Hall St Petersburg, 13 November 2020 ‒ 31 January 2020

A Korean star of contemporary art, Lee Bul started her artistic career at the turn of the 1990s with a search both for the right medium, arriving at the installation genre via performance and video art, and an approach to formal expression ‒ from biomorphic objects to finding geometric precision. After discovering for herself Russian avant-garde art in the noughties, the artist embraced its ideas of overcoming gravity of the Earth and a quest for a functioning fourth dimension, and it is not hard to understand why: Malevich’s famous statement that ‘the earth has been abandoned like a house eaten up with worms’ has not lost its magnetic appeal today. Two of the large projects that Lee Bul has been working on during the last decade are currently on view at the St Petersburg Manege Exhibition Hall, side by side with works by the artists who inspire her: pieces by Alexander Rodchenko, Lyubov Popova, Yakov Chernikhov, Alexander Labas and others were lent by various Russian collections.

Exhibition view. Photo: © Vasily Bulanov

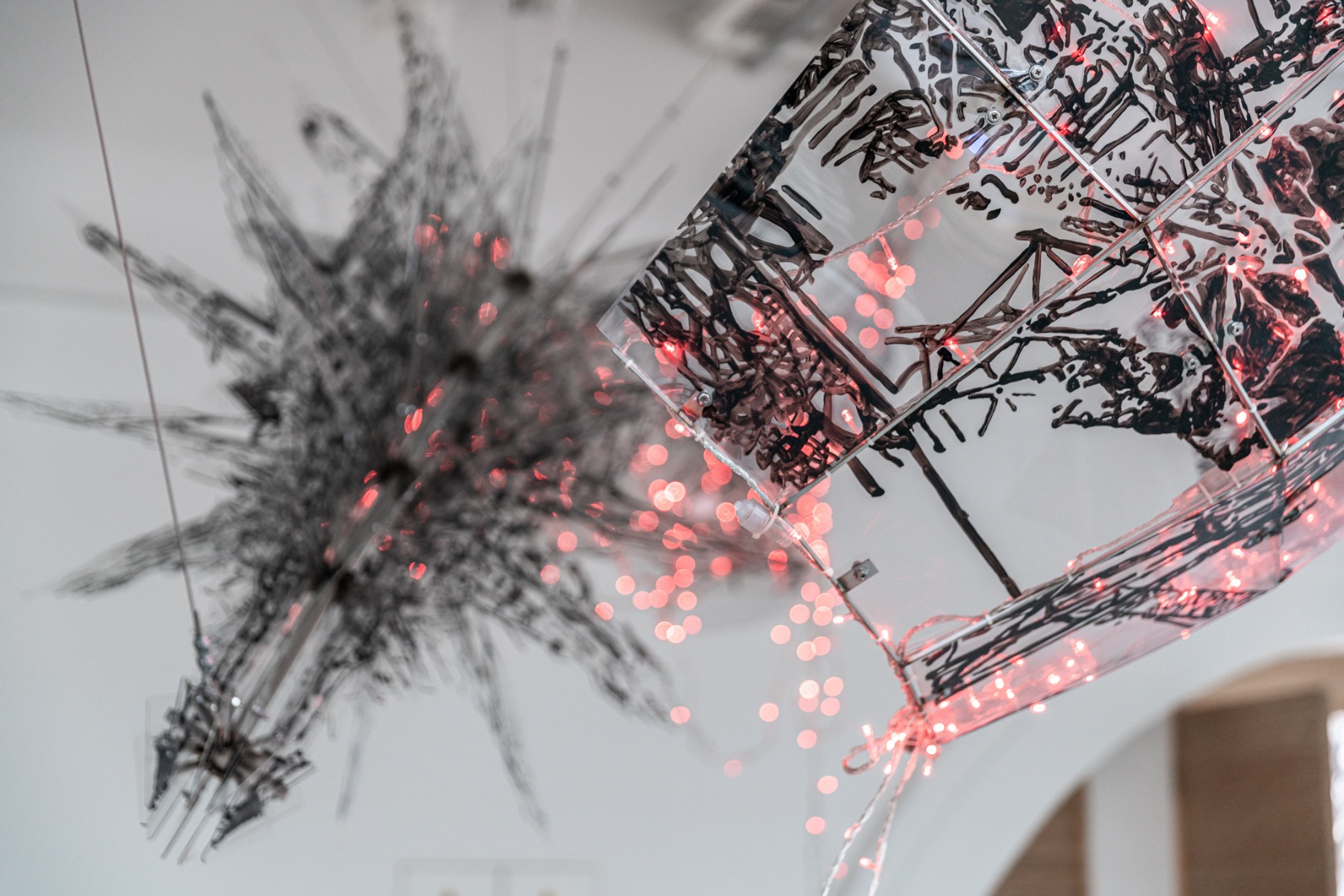

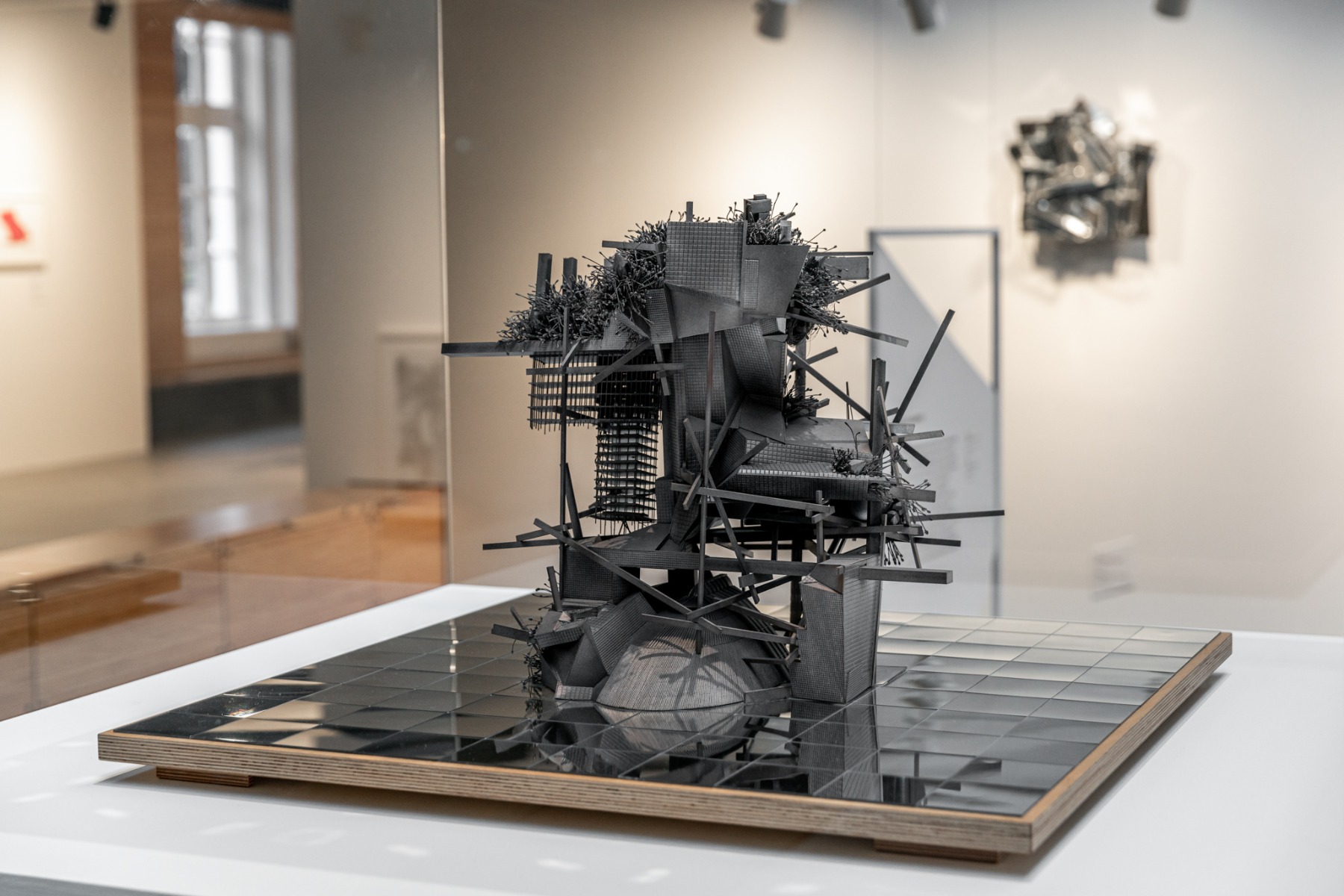

An extensive series of work under the collective title of ‘Willing to Be Vulnerable’ is scattered with references to zeppelins and circus tents. What they share is not just similarity of construction but also a spatial sense of an air mass, very successfully created inside the Central Exhibition Hall. The exhibition opens with a shiny cigar of an airship floating under the ceiling of the entrance hall and closes on the second floor with an installation representing falling debris of the burning Hindenburg, outlined with little red lights like a Christmas illumination. Air is the link that connects this with the other project, the mirror surface-filled ‘City of the Sun’. It was these famous words by Campanella that the Russian architect Ivan Leonidov borrowed to name the work of his final two decades of life ‒ the mysterious synthetic free-form project where his 1940s and 1950s watercolours, drawings and technical plans exceed any imaginable construction that could be built even today. On the other end of the Manege hall featuring the installation glistening in semi-darkness (Lee Bul has admitted to being inspired by the nocturnal Tokyo), a transparent floating sphere pays tribute to another of Leonidov’s unrealized projects, the famous Lenin Institute (presented in 1927 in Moscow), the architect’s sketches of which features a dirigible that has been moored to a mast. Of all the daring ideas, it was not at all the unworldly avant-gardists’ dreams of flying that were actually made real in practice ‒ just the option of travelling in an elegant passenger gondola of an airship that came to an end with a crash in 1937. It is hardly a secret that every utopia always ends with a crash.

Exhibition view. Photo: © Vasily Bulanov

It has long become something more than merely ‘the thing to do’ for contemporary artists to declare their love for the Russian avant-garde. Some of the recent blockbusters at the Hermitage immediately come to mind, including Anselm Kiefer’s exhibition dedicated to Velimir Khlebnikov, as well as Zaha Hadid’s, where the ‘Black Square’ from the museum’s holdings served as some kind of visual epigraph to the show. A relatively new thing in historical terms, the infatuation started soon after the publication of ‘The Great Experiment’ by Camilla Gray in 1962. Before that, Europe and America knew El Lissitzky and Wassily Kandinsky and were somewhat familiar with Kazimir Malevich, thanks to the works preserved by the Berlin architect Hugo Häring and later ended up at the Stedelijk Museum. Meanwhile, others remained practically unknown: of the artists who emigrated, only Ilia Zdanevich had some luck as a co-author of Coco Chanel and Marcel Duchamp, but not so much Pavel Mansurov or even Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, who both died in semi-obscurity. It was only in the 1980s that the situation started to change, culminating in 2014 with the Sochi Olympic Games, the opening ceremony being presented on a Suprematist-style set ‒ although this kind of official recognition was lightyears from the historical fate of the real works of art. And now the Russian avant-garde keeps serving as an endless source of design potential ‒ a field where the significance of Soviet Constructivism equals that of the German Bauhaus. Intellectual and artistic fashion moves in waves: the year is 2020, and a Korean artist in St Petersburg is examining her relationship with figures and ideas that have already become a common domain over the last half-century or so. ‘I want to create a sense of travelling in time through various historical periods. My works are something like a trip to another place and another time,’ the artist says.

Exhibition view. Photo: © Vasily Bulanov

The title of Lee Bul’s project is ‘Utopia Saved’ ‒ but who or what exactly is it that utopia needs saving from? Until recently, the answer was obvious: from Boris Groys and his book ‘The Total Art of Stalinism’, the content of which can easily be summed up in a single Nietzschean phrase: ‘birth of totalitarian art from the spirit of avant-garde’. Since then, the history of Russian culture of the first third of the 20th century has been explored well enough to be viewed in a not-so-straightforward ideological light. For any researcher of utopian ideas, architecture is the most valuable material of all: long before Lee Bul’s works, the subject was examined, among others, by Yuri Avvakumov in his ‘Russian Utopia: A Depository’ installation, a physical expression of his online Museum of Paper Architecture.

Exhibition view. Photo: © Vasily Bulanov

The genre of large-scale installation, the historical heir of the inevitable flamboyance and drama of ‘the big painting’, has long been suffering a crisis: it is other, more observant and detailed levels of communication that are becoming increasingly important today. And yet Lee Bul’s works appear somewhat like a scale-like row of hi-tech articles to the viewer’s eye; it is not a coincidence that the same device keeps reappearing in all of them ‒ a mirror-like surface and smooth, polished shapes, impenetrable and returning your gaze, which was never the case with ‘old art’.

Exhibition view. Photo: © Vasily Bulanov

Alongside these giant iridescent objects, a selection of works by 1920s and early 1930s artists, multiple times smaller in size, are shown. They hail from small, usually little-known museum collections, like the Labas from the Pskov Museum Complex or the Ekaterinburg Lissitzky. These are works that are by no means textbook examples, works that are giving the right hints to art obsessed with sheer grandiosity of forms and ideas.

Exhibition view. Photo: © Vasily Bulanov

Lee Bul’s exhibition was supposed to become part of the annual St Petersburg International Cultural Forum, proving the global significance of Russian culture to officials and bureaucrats. However, the forum events were cancelled due to the pandemic, and the propaganda potential was completely wasted ‒ a fact that did not influence the general tone of the exhibition. Bringing together revolutionary art and the circus, the artist is not that far from the truth. The famous cinematographic flight by the actress Lyubov Orlova as Mary [in the 1936 film Circus], who believes in miracles as she takes to the ‘skies’ of the circus tent dome, could well be considered to mark the end of development of avant-garde. And yet ‒ even at that point there is so much common ground shared by the acrobats on the trapeze and the geometric shapes in the pictures, just like by anybody who has ever managed to break loose from the Earth’s gravity.