An armchair journey of fictional travellers

A review of ‘(Dis)covering … Mountains / (Dé)couvrir les montagnes ...’ by Flo Kasearu and Sara B. Goulet

Sandra Vlasta

This travelogue has travelled to me both in intricate and simple ways. Intricate, as the reason I was invited to write about it stemmed from a conference in the United Kingdom, several workshops in Vienna and a journal issue published in Graz. Simple, because the book was sent to me swiftly: digitally, via the Internet. Consequently, there are many different ways to travel and just as many modes of writing about travel. Flo Kasearu and Sara B. Goulet’s ‘(Dis)covering … Mountains / (Dé)couvrir les montagnes ...’ explores a great variety of them.

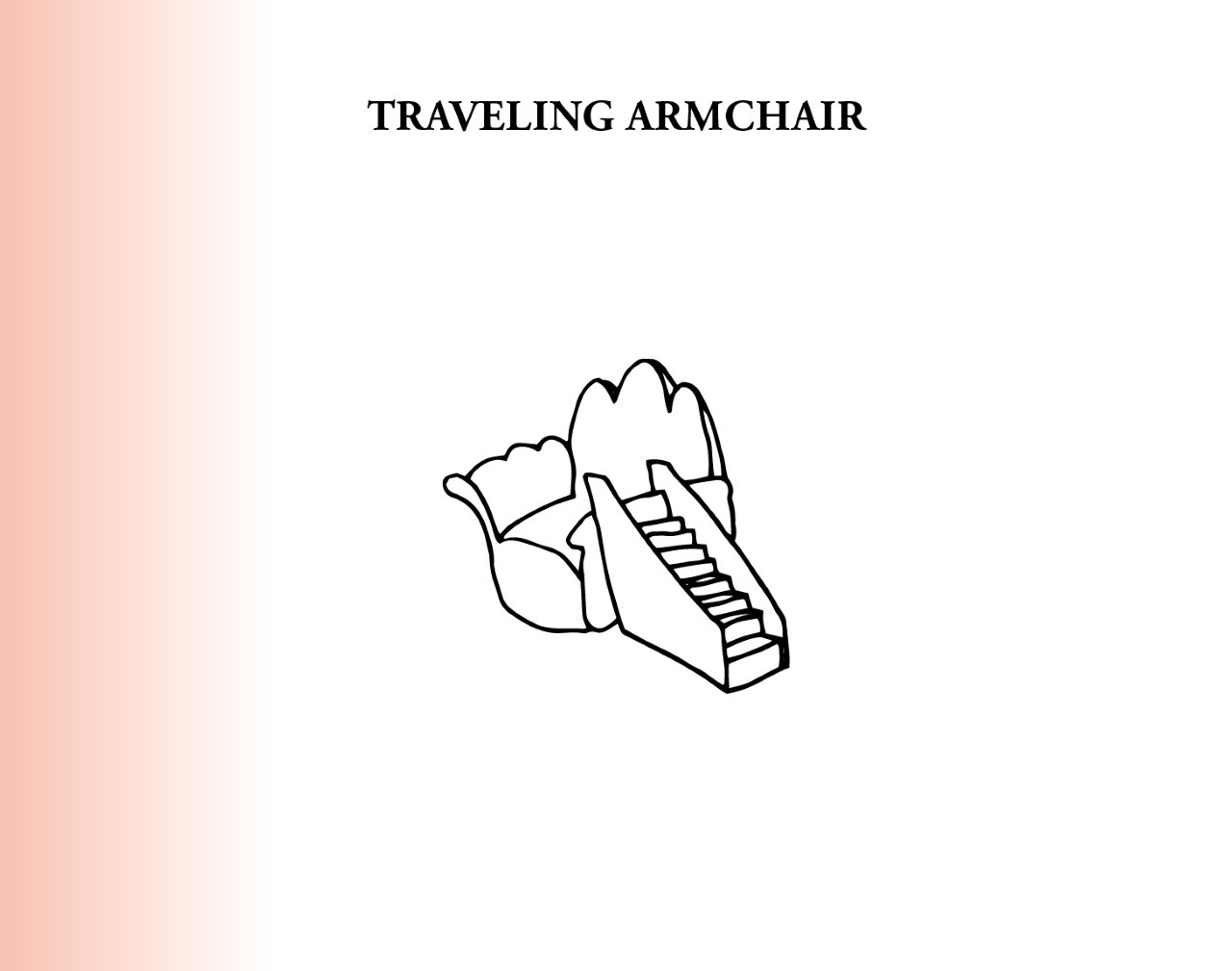

The book is a multilingual, intermedial and polyphonic travelogue that offers a timely and creative exploration of the experience of non-travel the world underwent during the coronavirus pandemic. The text, which was contemporaneously published in two editions – a French and an English one – is called a pocket book (livre de poche) and it has the typical format of travel guides. Even its colour – red – is reminiscent of the very first travel guides, Murray’s English ‘Handbooks for Travellers’ and Baedeker’s German travel guides (the first French travel guide series, the ‘Guide Bleu’, was, of course, blue). As can be seen on the publisher’s website, ‘(Dis)covering … Mountains / (Dé)couvrir les montagnes ...’ comfortably fits into the reader’s hand but just as well in their pockets. Accordingly, it might be carried anywhere the reader wants to take it – on a journey, perhaps to the very mountains of la Barasse, “a hilly area, on the outskirts of the city” (p.16) of Marseille where the travelogue is partly set, or just to the reader’s favourite reading place, maybe the “travelling armchair” that welcomes us right at the beginning of the book:

Once the reader has settled in this comfortable piece of furniture, they realise that this is going to be a peculiar journey whose path leads them through both texts and sketches, hence it has intermedial qualities. In fact, ‘(Dis)covering … Mountains / (Dé)couvrir les montagnes ...’ is the result of a collaboration between artist Flo Kasearu and writer and academic Sara B. Goulet, hence the polyphonic character that unites different voices that are expressed in individual ways, namely written and drawn. The voices of the two - as artists, narrators or travellers - complement each other in unique ways and present a dialogue about (non-)travel that becomes a travelogue in its own right.

The book originates from ‘Roots to Routes’, a collaborative project between artists, curators and non-profit organisations from Marseille and the Baltic countries. ‘Roots to Routes’ asked strangers to encounter the unknown and unfamiliar within the urban environment – in the case of Sara B. Goulet and Flo Kasearu’s travelogue it was Marseille – and to explore and challenge the concepts of home, belonging and identity, at the same time. ‘Roots to Routes’ became based on Georg Simmel’s definition of the ‘stranger’, attributing them the role of importing qualities into a community which cannot come from the group itself. Flo Kasearu and Sara B. Goulet became such strangers, although originally it seemed as though only Flo was supposed to have left Tallinn for Marseille in the middle of March 2020. Flo had planned “to discover and understand La Barasse, its underground culture and landscape about which she had only heard through her narrator” (p.16). Indeed, the very title of this travelogue is a reference to Flo’s search for the famous red mud mountains of this region. What gets clearer towards the end of the travelogue is that the project was already in danger and even if Covid-19 had not fully hit Europe yet, neither the artist, nor “the traveller of 2020” – to whom the authors dedicate special thanks to – were ever in a position to be able to depart or embark on such a journey. “If the key to travel and its writing is distance, then being away from one’s destination could provide an optimal point of view.” (p.39) It is at this point that the two rethink the whole idea of distance in relation to travel and form a new perspective for the book.

In fact, it is not only the actual distance, but literature, and in particular travel writing, that allows them to look at their destination from afar, helping them reframe their journey. Eventually, Flo and “her narrator” decide to depart together after all, on an ‘armchair journey’, so to speak. As readers, we are invited to join them and become Flo’s ‘Sancho Panza’ and her ‘Passepartout’, Phileas Fogg’s companion on his journey around the world in 80 days. The two artists (and we as readers) become fictional travellers, just like Odysseus, who also gets a mention. This inter-textual quality underscores the text’s connection to a whole universe of fictional travellers, which further emphasises the general make-believe of travelling during times of coronavirus. Ultimately, haven’t we all had to become fictional travellers to some extent? At the same time, Flo and the narrator are both protagonists and writers of a travelogue, similar to the ones inspiring their writing, who are cited at the end of the book, including: travel writing by Bougainville, Chateaubriand, Marco Polo and Stendhal, amongst others. Thus, ‘(Dis)covering ... Mountains / (Dé)couvrir les montagnes ...’ opens up a complex network of travel literature.

A striking aspect about this travelogue is the combination of text and sketches. On the one hand, this is not a new combination. Visual elements have been included in travel writing for a long time, be it maps, pictures, drawings or photographs. On the other hand, there are very few travelogues where we find such a balanced relation between text and image as we do in ‘(Dis)covering ... Mountains / (Dé)couvrir les montagnes ...’. Whereas in most other travel accounts, text predominates and illustrations add authenticity to the narrative to help render it more credible, in this pocketbook, text and sketches equally share the space. Moreover, not only do they share the space, they also intermingle: at times, text is surrounded by drawings and the sketches move closer to the text, sometimes becoming representational, at other times in a more ornamental manner, such as the use of small symbols to mark new paragraphs.

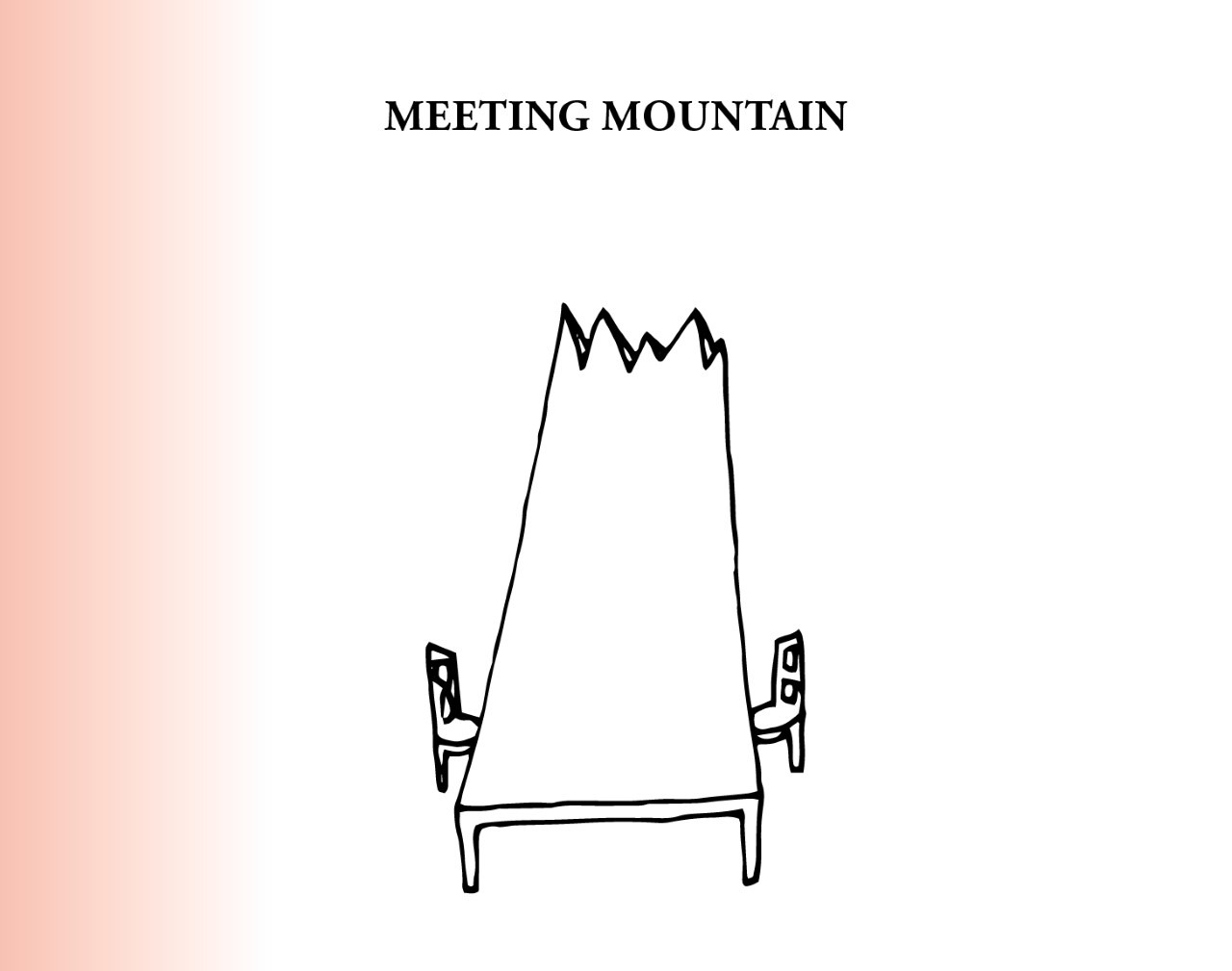

Drawn with clean, simple, black lines, the sketches might be read as maps that accompany the written account, though contemporaneously they create their own narrative, travelling along mountains and other sceneries as well as the domestic landscapes we have all become too familiar with during months of confinement: sofas, tables and chairs etc. These diverse landscapes intertwine, such that one can even see the mountains - perhaps representations of the area of ‘la Barasse’ - simultaneously transformed into furniture:

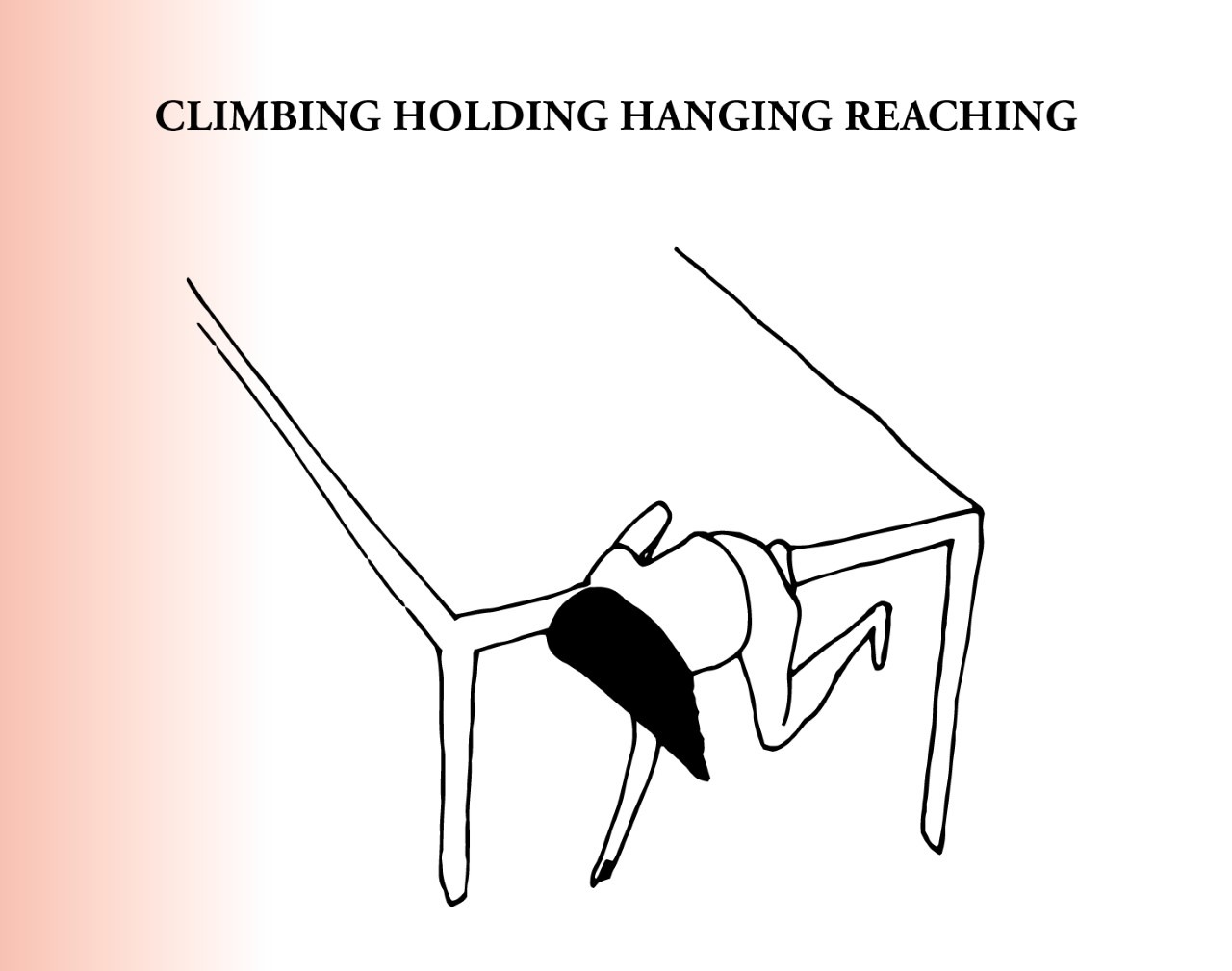

In fact, even Marseille is, at times, depicted as a table. In times of non-travel, though far-away places are physically inaccessible, we might still be able to experience them through fictional travelogues, through inventive, make-believe writing or sketched journeys and, at the very least, through our imagination that can transform a kitchen table into a mountain to be climbed or held on to (just like we hold on to the idea of travel):

‘(Dis)covering ... Mountains / (Dé)couvrir les montagnes …’ introduces an innovative relationship between text and image in travel writing, a genre in which the text firmly positions itself. This positioning becomes evident through the allusions to several typical tropes of the genre, such as references to means of transport, to the itinerary, to earlier travellers and to other travelogues. Furthermore, the diary-like structure of the text, complete with some exact dates, as well as its dialogical character (mostly communicated between Flo and the narrator) seem reminiscent of other epistolary travelogues, for instance epistolary ones. The blending of fact and fiction is also a typical feature of travel writing, undertaken very explicitly in this travelogue by intermingling Flo, Sara and the readers with the fictional travellers mentioned above.

Besides, other inter-textual references that are not explicitly expressed in this pocket book invite one to read it as a travelogue: the journey via cities and chairs, mountains and mantelpieces, rocks and racks reminds readers of travelogues that describe similar non-travels, such as Xavier de Maistré’s ‘Voyage autour de ma chambre’ (1794). Apart from the scenery created by pieces of furniture, there are more parallels between Kasearu and Goulet’s book and Maistre’s: because of a legal house detention, Maistre was confined to being indoors for a period of 42 days. In his autobiographical text, Maistre describes his various steps and routes through his room during that time. He used furniture and objects as starting points for various narrations and reflections. In ‘(Dis)covering ... Mountains / (Dé)couvrir les montagnes ...’ it seems to be the other way around: the places that were not visited stimulate the drawings of the pieces of furniture and other objects. These are, in turn, affected by the narrative and transform into mountains, cliffs and other geomorphic forms.

Like so many journeys, this travelogue also comes full circle. It supposedly ends, where it started, namely in March 2020 with the statement: “Flo would have left Tallinn on March 18,” (p.44). This end is only a suggestion made in a dialogue between Flo and the narrator, pondering the question of how to go on with such a project despite the constraints coronavirus had imposed on them. We learn from the very beginning of the text, which starts with the same phrase, “Flo would have left Tallinn on March 18” (p.7), that the two had decided to proceed with their project and developed a form of a travelogue about a journey that could never have been executed. The result, after all, is a travelogue that undertakes a number of tours: to Marseille, to la Barasse, but also to the visual performance of a journey and to those moments of uncertainty we all experienced at the beginning of the first lockdown in spring 2020. In this manner, coming full circle does not mean ending where one started: on the contrary, the journey in between has an effect on all the travellers involved, be it the sketcher, the narrator or us, the readers. We follow the itinerary along a mountain range and witness the changes along the way: La Barasse’s red mud mountains slowly leaking into the sea, the sketched furniture morphing into the landscape, the traveller that traverses fiction as they are not on any physical journey, after all. Fittingly, the travelogue is concluded with Jean de la Fontaine’s interpretation of ‘The Mountain in Labour’, an appropriate choice considering the transformative aspect of the mountains described and sketched in the book. This travelogue’s result, however, is much more significant than the mouse (or dearth) mentioned in the original fable.

***

(Dis)covering ... Mountains / (Dé)couvrir les montagnes…

Flo Kasearu & Sara Bédard-Goulet

Graphic design by Viktor Gurov

Proofreading by Ryan Galer and Adrian de Banville

Published in English and French

Roots to Routes, 2020