«HUMANITET». The Power of Art in Troubled Times

The exhibition is on display in Stockholm until September 11

On April 8, 2022, “Humanitet. The Power of Art in Troubled Times” exhibition opened to reveal and revisit the work of Vera Nilsson, Sven Xet Erixson, Bror Hjorth, and Albin Amelin – the most popular Swedish modernist artists of the first half of the 20th century. Works created in the mid-1920s to the mid-1940s are on display. The exhibition’s curator Paulina Sokolow interprets the two decades as a single period, a kind of long 1930s. She sees the 1930s as a turning point for Swedish art and society – a time of international turbulence and breakthrough reforms.

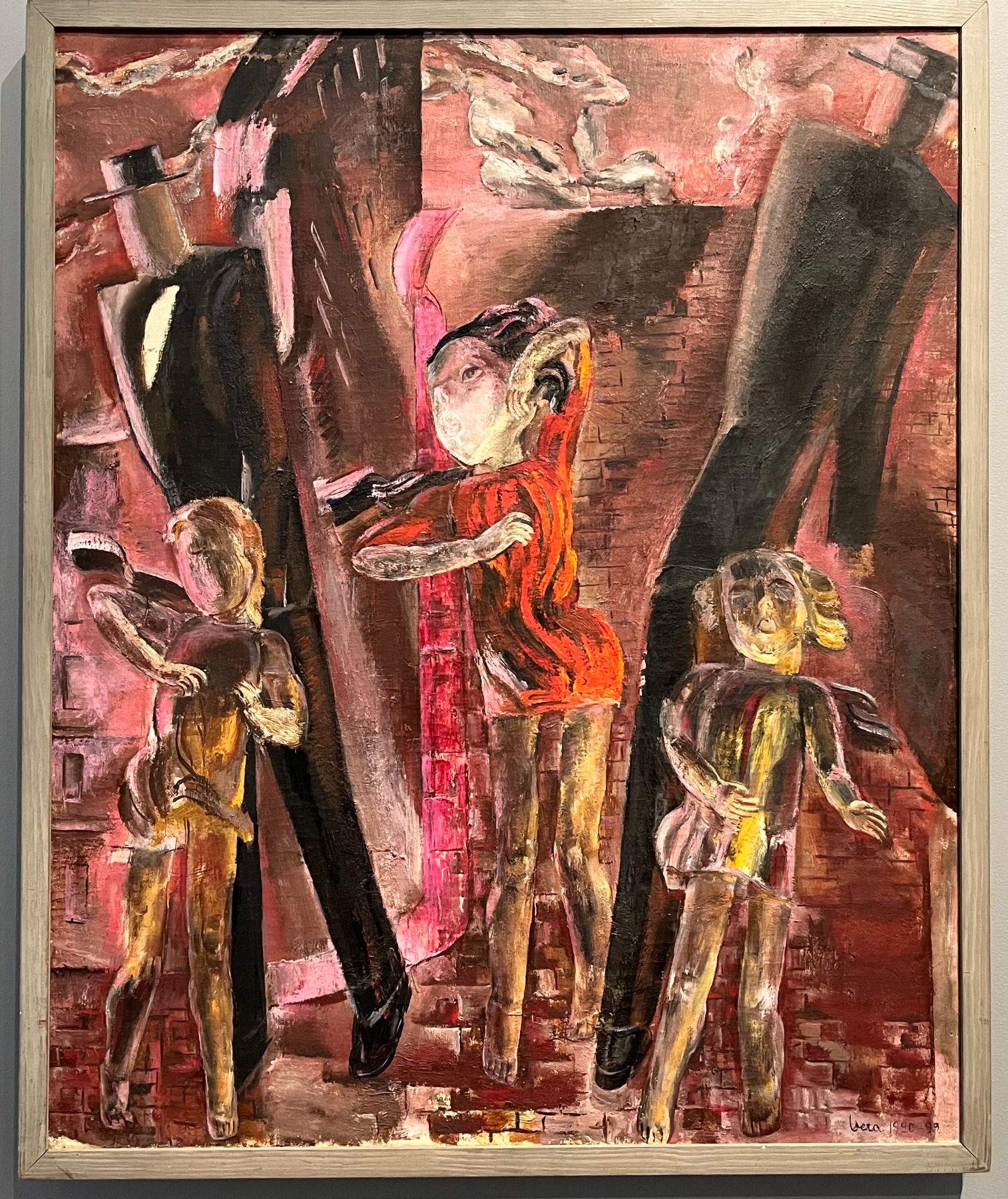

Money Versus Life by Vera Nilsson, 1938

Of all the Swedish modernists these four were chosen as “the greatest chroniclers of their time”, who witnessed and depicted Sweden entering the new era: the era of industrialization, development of hydropower, electrification of streets, growth of cities as a result of massive urbanisation of rural populations.

River of Time by Sven Erixson, 1937

These artists’ lives are intertwined with the history of Europe, and the images of the war are exhibited next to the portraits of children and paintings inspired by foreign trips. The curator emphasises that it was important for the artists to be part of the events. Art was a way for them to talk about their time, to participate in historical events and even influence them.

On the Terrace, Rome by Vera Nilsson, 1926

The four artists have similar life stories: all of them came from middle class backgrounds, entered the art scene in the 1920s, studied abroad and became part of the international art exchange. In Sweden, they were active in establishing the institutions that support arts. In 1932, during the economic crisis, they founded their own Colour and Form gallery in order to sell their work bypassing commercial galleries and to reduce their dependance on art museums. Many of their initiatives of the 1930s still exist in today’s Sweden. For example, thanks to the efforts of Sven Eriхson and Albin Amelin, the Public Art Agency of Sweden was founded in 1937, and a bill directing one percent of any building project funds to finance public art was passed by the parliament

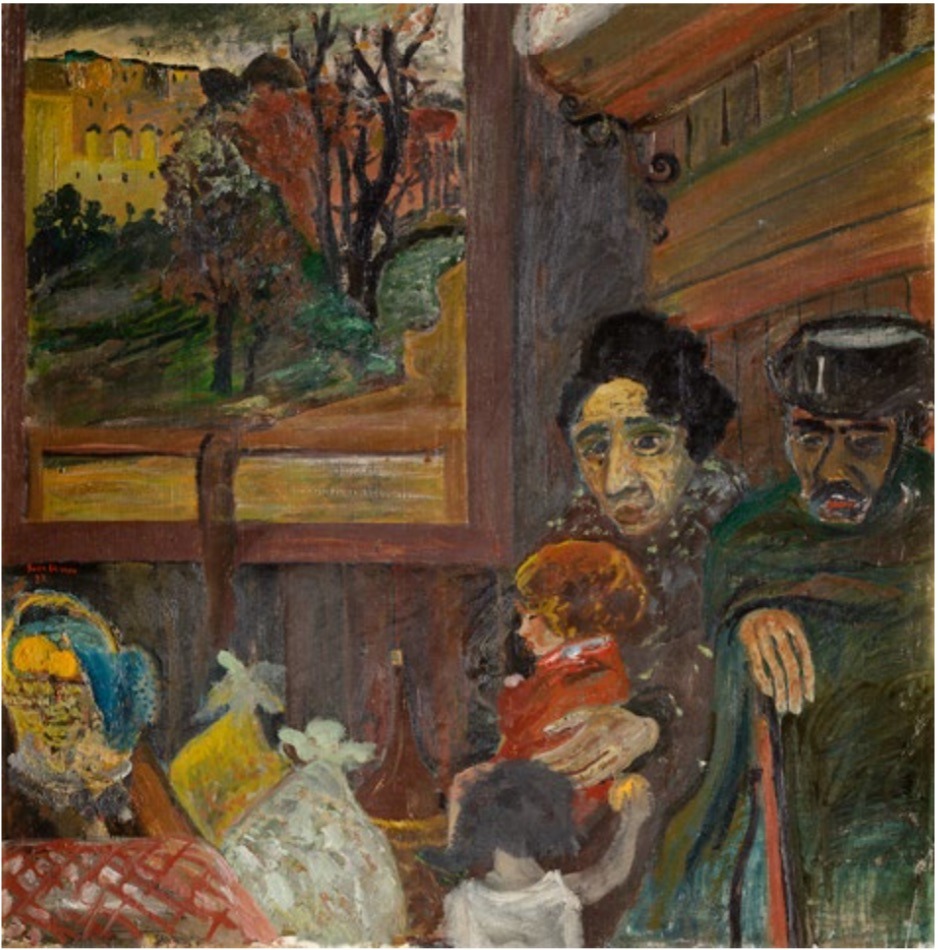

Family by Bror Hjorth, 1932

“Humanitet” occupies three floors of Sven-Harrys konstmuseum. Clusters of travel, family, and modern city images make up a loose structure of the exhibition and introduce viewers to the context the artists worked in and responded to. The most expressive and unexpected features of the exhibition are colour and form, those very notions the artists used to name their gallery and as a tool to express themselves and to communicate with others. “Everything began in a tube of paint or some glorious piece of wood or clay, – the curator writes, – and without these materials, nothing could ever be born, or lead on to anything new.” Indeed, what captures you from the first sight at “Humanitet” is the quality of art.

Melody of the River by Sven Erixson, 1935

The exhibits at the ground floor make a particularly strong impression: the two halls house expositions opposed to each other artistically and emotionally. The first makes viewers immerse into the world of art and artistic problems of the 1920s and 1930s, into international modernist space between the two wars. The pieces here remind us of the works by their contemporaries in Germany, France, Italy, the Soviet Union. Though some remarks on the museum labels bring us back to the conservative context of Northern Europe: “Love” by sculptor Bror Hjort, who came from France as a student of Bourdelle caused a real scandal and was deemed totally obscene.

Gandhi by Bror Hjort, 1936

The wood carved portrait of Mahatma Gandhi by Bror Hjort is the first thing you see when you come to the exhibition of Swedish modernists. This figure, not quite expected here, indicates the international scale the artists thought themselves in. In addition, Gandhi, who launched his peaceful resistance in India in the 1920s and became a symbol of anti-imperialism, is placed here as an antipode to Hitler.

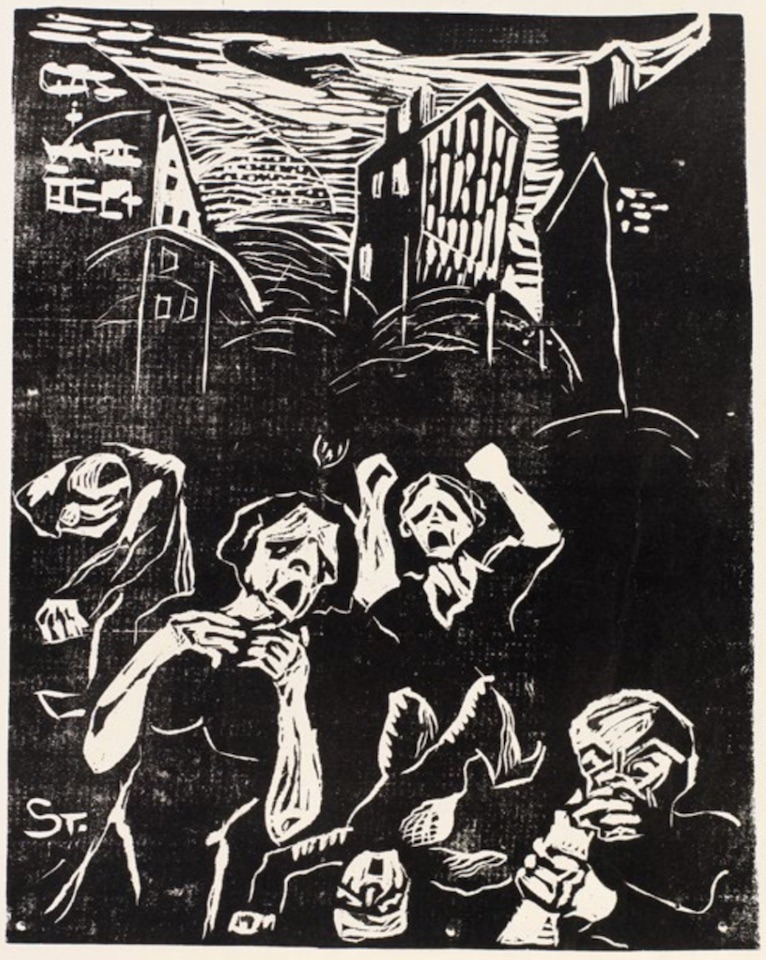

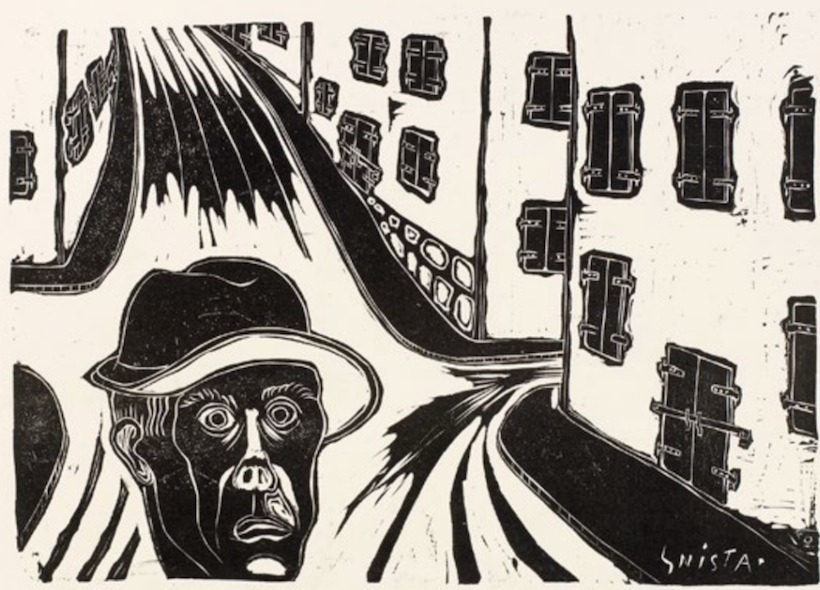

Picture from Humanitet publication

If the first hall is about diversity of art and life, then the second is overwhelmed with images of horror and violence. The anti-war graphic of “Humanitet” one-off publication shown here gave title to the exhibition. “Humanitet” was published in October 1933 as the artists’ immediate response to Hitler’s rise to power in Germany. It’s a collection of 17 anti-war black and white linocuts, expressive, concise and creepy, screaming of the threats of fascism and the inadmissibility of war. The cover linocut shows a military man’s face with a huge ragged hole instead of nose and mouth. A scream is almost audibly breaking from this frightening blood-red wound.

Picture from Humanitet publication

Sven Erixson and Albin Amelin who initiated this publication chose the cheapest paper and printing technique to increase the circulation and make “Humanitet” available to the wider audiences possible. They didn’t put any text intentionally, being confident that visual language would be more eloquent and comprehensive. Not only the publication became a fact of resistance, it also proved that art was a means of communication. The authors believed that people, blinded by fear and uncertainty, adapted themselves to violence and atrocities, and that the art could be used as a tool to address viewers directly, it was the way for the artists to face their viewers and tear them out of shackling indifference.

Street in Malaga by Vera Nilsson, 1920

During the Second World War, Sweden remained neutral, and retrospectively it looks like the most advantageous position for an artist to express. But in the 1930s, when “Humanitet” was published, Swedish society was highly divided and polarised. From the mid-1920s, such fascist organisations as the Swedish National Socialist Farmers’ and Workers' Party or the Swedish Fascist Combat Organisation were present. Many people who did not share the fascist ideology still considered it important to avoid irritating Germany, whose’ influence was quite visible. That is why, despite the original idea, “Humanitet” came out with a circulation of only 100 copies. Publishers were reluctant to sell and advertise it. Another anti-war magazine, “Mansklighet” (Humanity), first published in 1934, brought together the work of artists and anti-fascist writers, but was soon closed under the formal pretext of allegedly insufficient quality of the material. Under these conditions, anti-war graphics and the appeal of artists to the divided and frightened society was in fact an act of courage.

Spanish Refugees by Sven Erixson, 1927

The second hall is full of accounts of disasters brought by war, poverty and disease. Next to the anti-war graphics of “Humanitet” and “Mansklighet” there is Vera Nilsson’s Street in Malaga, depicting children dancing on the street for money. The dance takes place in Spain, which has recently experienced a flu pandemic. With characters’ proportions distorted, poses unnatural, they resemble mannequins rather than people, and the landscape is blocked by a blank brick wall illuminated by pink flashes of light. The language of surrealism is the best to show how fragile the border between life and death can be.

Several works by Erixson here are dedicated to refugees, those who were thrown into the unknown by the war, that took away their homes, their relatives, their entire past. They fled the Spanish Civil War and the spread of fascism across Europe. In 1942, Erixson created a sketch for the Moonlight Massacre tapestry in response to Sweden’s refusal to accept German anti-fascists and Jews during the early years of the war. The Moonlight Massacre depicts one of the bloodiest battles in Scandinavian history. In 1361, the Danish army attacked the island of Gotland. Local farmers sought refuge inside the city walls of Visby, but the townspeople did not open the gates. Centuries after the event archaeologists discovered multiple burials of defenceless people who were not granted a shelter within the walls of Visby.

Moonlight Massacre by Sven Erixson,1963, tapestry based on a 1943 sketch

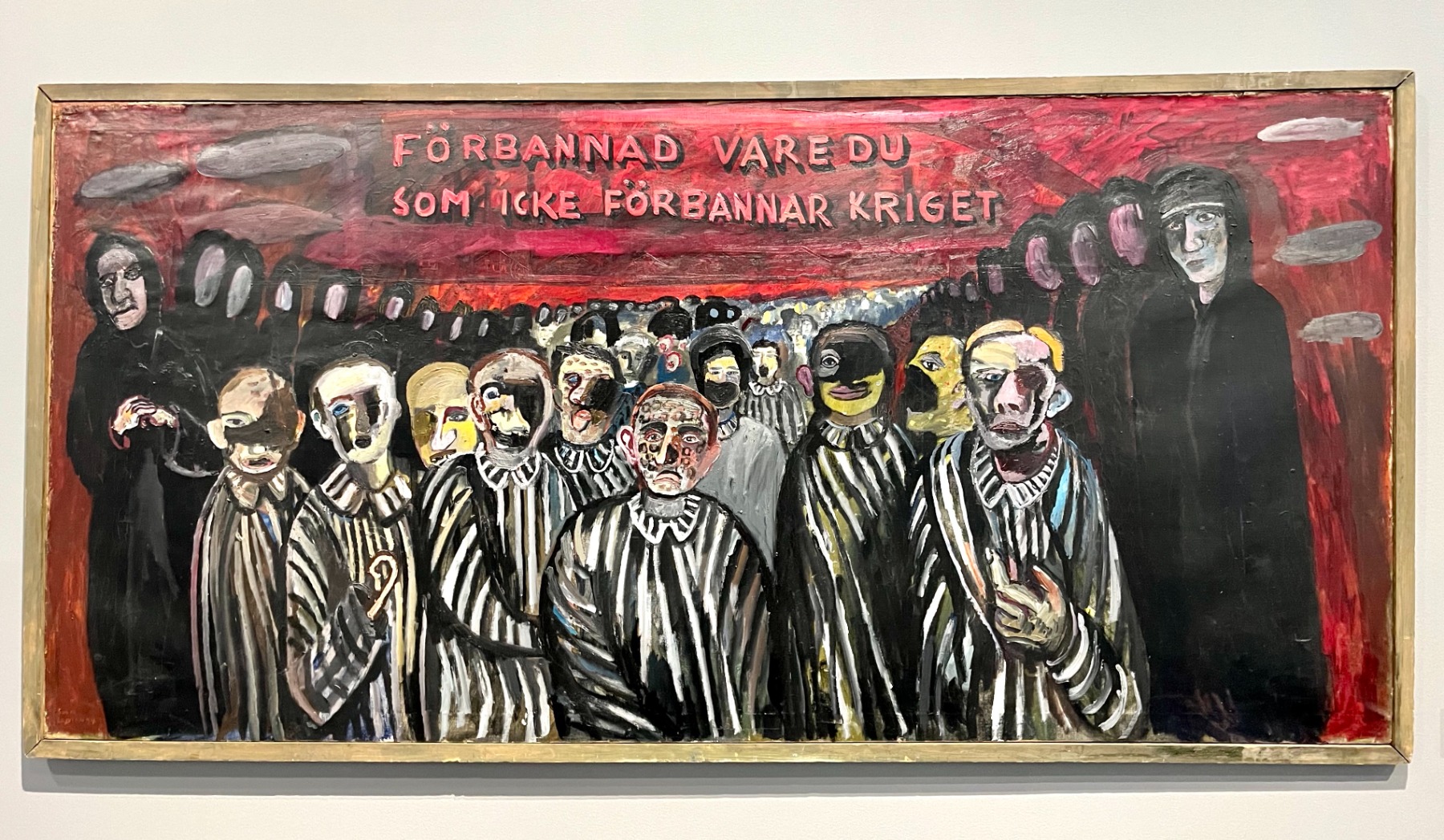

Right in the centre the most disturbing image of the war is placed, created by Sven Erixson in 1944. Mutilated concentration camp prisoners stand in front of the viewers and look straight in their face. They are infinitely numerous, the edge of the crowd dissolves into the depths of the picture. Placed under a blood-red vault of either sky or dungeons, framed by silent and lifeless rows of widowed women, with insane expressions on their faces, leaky eyes, severed noses, torn mouths and scabbed skin, they reveal the very essence of war. An inscription on the canvas turns it into a large pictorial poster. In 1944 an image seemed not enough anymore, and the artist literally shouted the words out: “Cursed are you who do not curse war!”

Cursed Be Those Who Do Not Curse the War by Sven Erixson, 1944

After the Second World War, a new generation of artists emerging on the Swedish art scene, chose a more detached and abstract version of modernism. All the four artists presented at the “Humanitet” are well known in Sweden, their works are on display in Swedish museums, nonetheless curator Paulina Sokolow stresses the point that this is the first exhibition to highlight specifically their work in the 1930s. For quite a while, this period, and especially their anti-war images, remained virtually unknown and forgotten. But it’s the artists’ involvement in the political environment of the time, their desire to participate in events instead of observing them from the outside, seems to be especially important to the curator. Quite unexpectedly the forgotten 1930s become a reason to believe that art can participate in ordering the world.

Much is said about this in the articles of the exhibition catalogue. “The 1930s remain provocative to this day,” – Cecilia Wiedenheim, an art critic, writes. She tells the story of Picasso’s Guernica, another piercing voice from the 1930s. In 1938, Guernica was shown in Stockholm at the Liljevalhs hall, then it travelled around world for many years before ending up in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. During the Vietnam War, Guernica became the target of anti-war demonstrations: in 1974, the words “Kill Lies All” were written on it in red paint to protest against President Nixon’s policy. A few years later, Guernica was transferred to the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid and a tapestry copy was made to be placed at the entrance to the United Nations Security Council Chamber in New York. When US Secretary of State Colin Powell argued in favour of the Iraq War in February 2003, the tapestry was covered with a blue drapery. “Apparently, a call to peace from the 1930s was too much for the United Nations to stomach in the early 2000s,” – Wiedenheim concludes.

The exhibition of Swedish modernists who opposed violence, war and totalitarianism in 1933 was being prepared for two years and opened in the spring of 2022, when the whole world stood in a daze, watching the bombing of Kyiv, Kharkov, Mariupol, Odessa; seeing millions of people lose their homes and fleing into the unknown for their lives. Art seemed to lose all its meaning juxtaposed to the horrific reality. Contrary to this feeling, the “Humanitet” and its artists testify that the role of art in troubled times is greater than ever.

Title image:Refugees at the Malmö Museum by Sven Erixson, 1945