Mobilized Against Evil

Women At War. Curated by Monika Fabijanska. Fridman Gallery, New York

A small but powerful exhibition at New York’s Fridman Gallery seeks to give some foreground on the female perspective of a military operation that has been active since 2014. Writing as a Russian national, one has to question the motivations behind every supportive word. It is true that since 2014, Russians, even those in opposition, have been using a passive voice in relation to the conflict in eastern Ukraine, rarely standing up to the escalation of state propaganda. T. S. Eliot’s landmark poem “The Hollow Men” takes its title and inspiration from Joseph Conrad’s account of British colonial violence in the novella “Heart of Darkness”. With this war, Russians have found themselves to be hollow, too, and the ways to overcome this state is to listen to Ukraine’s reliable narrators.

Olia Fedorova, Defense, 2017, photograph, 15.7 x 19.7 in. © Olia Fedorova. Courtesy of the artist

The curator, Monika Fabijanska, is no stranger to feminist art and violence as a topic: her 2018 show “The Un-Heroic Act”, at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice of the City University of New York, had gathered together 20 representations of rape from female American artists of all generations. “Women At War” is, of course, just as timely and important. Moreover, it has been recognized as such by the mainstream American press, with glowing reviews appearing in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, and a number of specialized arts publications. This is not only a consequence of the war in Ukraine being a trending topic in the American media – the strength of the work in the show is undeniable, and one can only rejoice at the potential horizons that have opened for the artists and only hope that they are here to stay regardless of the fate of their homeland. What’s also admirable is how the curator uses historical material to contextualize many instances of Russia’s imperial choking of Ukraine, a process that has been going on for centuries. This has not been a gendered practice, and an exhibition on «men at war» is certainly possible, with work that is no worse than the selection at Fridman Gallery. But an accent on the female experience is always welcome because their suffering is often overlooked. It makes sense, as Martha Schewender writes in her review in the New York Times, to think of this era as the era of female testimonies, irreversibly turning our cultural experience of war towards first-person accounts of the weak and the dispossessed.

Alena Grom, Mother and Son. Mariinka, Donbas (Womb series), 2018, photograph, 11.8 x 17.7 in.

© Alena Grom. Courtesy of the artist

The earliest work here is by Alla Horska, a monumental painter who is believed to have been killed on orders from the KGB in 1970. Most of the pieces were made before February 2022, and that gives a sense of historical continuity to a war that has been all but ignored in the global media. Two photographic series in the exhibition – “Womb” by Alena Grom, and “Victories of the Defeated” by Evgenia Belorusets – starkly relay the inhuman conditions of the war for the east of Ukraine. In “Womb” (2018), Alena Grom photographed young mothers who had to give birth in bomb shelters, whereas over the last few years Evgenia Belorusets has explored everyday life in the Russia-backed separatist enclaves of eastern Ukraine, documenting biographies gone sideways, broken families and lost jobs, all taking place under a very real threat to life.

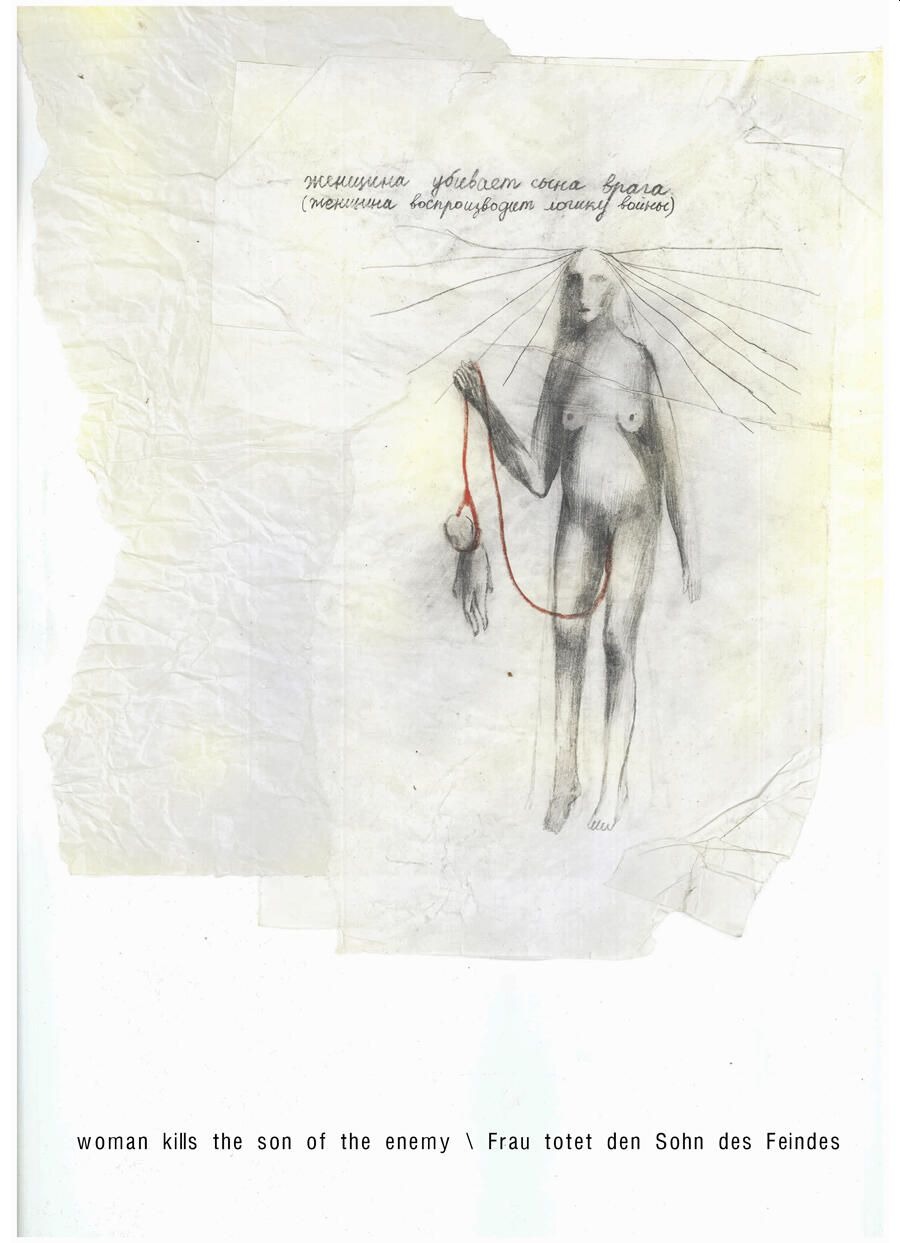

Dana Kavelina, woman kills the son of the enemy (Communications. Exit to the Blind Spot series), 2019, graphite and colored pencil on paper, 32 × 30 cm. Courtesy: the artist

The Empire’s debilitating presence knives through all the works in the show in various forms, and is even more profound because of the feminist focus of the exhibition. “Every war is a war against women,” writes Dana Kavelina in a 2020 text quoted in the curator’s essay. And while the media’s perception of the war focuses on territories, destruction of infrastructure, and positions of armed forces, all these schematic projections of lived experience cover up one of Russia’s main objectives: artificially inflating the number of Russian citizens through the illegal annexation of Ukrainian territory; these forced “citizens”, especially women, are needed in order to boost the population of a country with a drastically decreasing birthrate.

Dana Kavelina, a still from Letter to a Turtledove, 2020, film, 20:55 min.

© Dana Kavelina. Courtesy of the artist

Kavelina’s video “Letter to a Turtledove” (2020) links the earth, the female, and the destructiveness of war in a shockingly effective way. It is a poetic essay on the fate of the Donbass region in the 20th century told through a series of archive footage reels, private videos from the war zone, and collage animation in the style of Hannah Hoch or John Heartfield. It is arguably the definitive work on the storied history of Donbass, a place that has seen itself lionized in Soviet propaganda, abandoned economically since late socialism, and often seen as a cultural and political problem in the years of Ukrainian independence. Kavelina’s metaphors conflate the earth’s bountiful presence with war’s destruction and women’s fates, situating every aspect of Donbass’ history against the horror of forceful invasion: by industry, by the military, by men. Kavelina’s drawings from the series “Mother Srebrenica Mother Donbass” directly address the physical and mental trauma of wartime rape.

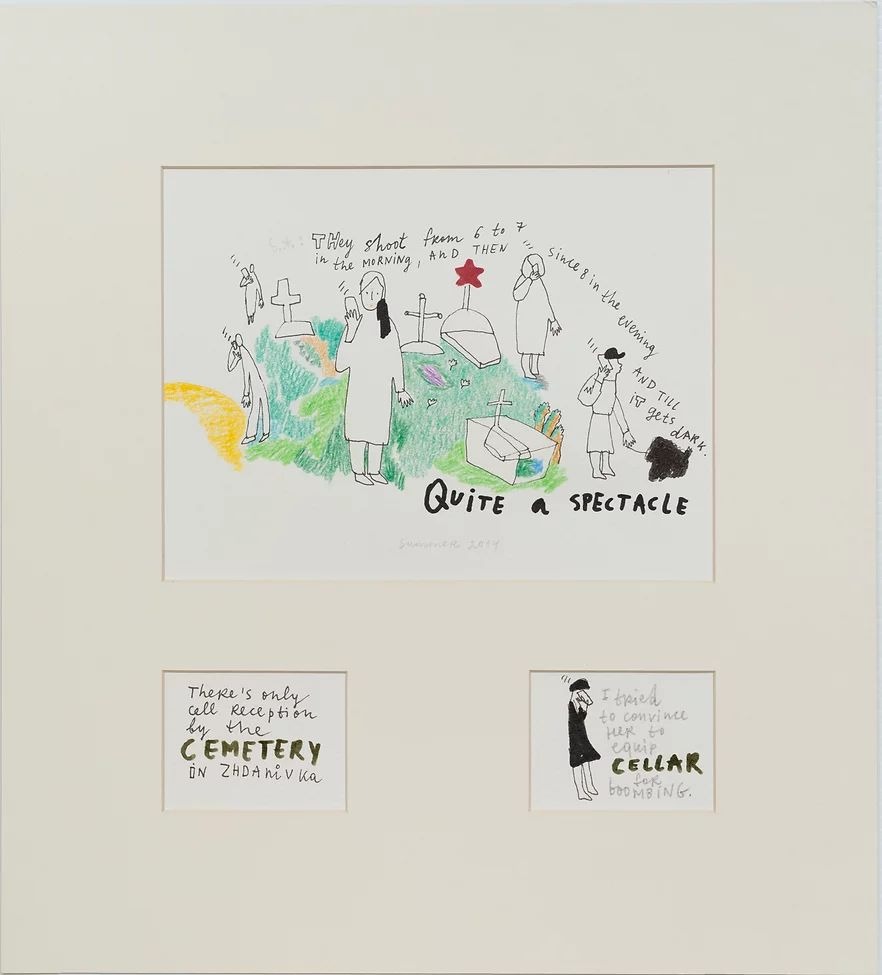

Alevtina Kakhidze, Strawberry Andreevna #3, 2014, ink drawing, 16.5 x 15 in.

© Alevtina Kakhidze. Courtesy of the artist

Two of the works in the show are diaristic, a form that often provides existential structure to periods of precarious existence. Alevtina Kakhidze has been commenting on war and its implications for the world since the very start of the invasion. Her political cartoons harshly debunk each and every attempt at doublespeak from both the Russians keen on protecting the sanctity of “Russian culture” and, by extension, their position, and the European politicians that cannot instigate large-scale boycotts of Russia’s energy imports. Hers is a position of a voice crying in the wilderness of self-interest that surrounds the war. Vlada Ralko, probably the most accomplished artist in the show with many exhibitions to her name, presents a graphic, in every sense of the word, diary of wartime, with bodies distorted by missiles, tanks, and the two-headed eagle. First-person accounts are a powerful cultural weapon for the marginalized and the weak, and they have been used many times during this war, most recently in “Herstory of the war”, an online exhibition of Kharkiv’s Gender Museum.

Women At War. Exhibition view at New York’s Fridman Gallery

When not diaristic or documentary, the works in the show deal with figurative narration. Lesya Khomenko’s monumental full-body portraits of soldiers serving in Ukraine’s territorial defense were the monumental core of “This is Ukraine: Defending Freedom”, a pavilion produced by the Pinchuk Art Centre at the latest Venice Biennial. In “Women At War”, she shows a portrait of her husband painted in March 2022 – an image of mobilization against evil that effectively imparts the immediacy of his new vocation. Anna Scherbyna’s suite of miniature paintings shows the recent ruins of buildings in Donbass and has been made during her travels with the human rights organization Vostok SOS through the regions of Luhansk and Donetsk.

Women At War. Exhibition view at New York’s Fridman Gallery

For a long time now, all these testimonies from the war zone have been emerging only from the Ukrainian side of the divide. It would take one hand to count the number of Russian artists going across the border, and no work on the topic has been produced as far as this author knows. The situation there was not taken seriously enough and certainly did not seem to have the potential for escalation. But maybe the difference is cultural as well. Russian art has long been plagued by a sense of imperial fatalism, so to speak. It was rare for the culture to address pointed political critique to the powers that be. Underground artists in the 1960s–1980s were either pursuing goals that connected them to the European mainstream (or their version of it as glimpsed through rare encounters with magazines and collectors from the West) or mocking the Soviet Empire by deconstructing its visual language. That hasn’t changed in recent years, and since 2014 the Ukrainian art scene has evolved in a markedly different direction, with most practitioners tackling the question of hybrid war tactics of Russian ressentiment. Now the ressentiment, or postcolonial melancholy, as Paul Gilroy has called it in relation to modern Britain, has to be acknowledged in full among Russians, too. The testimonies in “Women At War”, and many other artworks that have been created by Ukrainian artists and filmmakers in the last eight years, must serve as the base of this recognition that is coming so very, very late.

Title image: Yevgenia Belorusets, Victories of the Defeated, 2014-2018, photographs and texts. © Yevgenia Belorusets. Courtesy of the artist