The story of fragility

Mariona Baltkalne*

Ceramics intervention Foetal Attraction by Paddy Hartley at the Rīga Stradiņš University Anatomy Museum

The beginnings of science communication can be traced to Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome; however, the concept of communicating science fully matured in the 20th century as the development of specific fields of science promoted the necessity for such communication. Terry W. Burns, D.J. O’Connor, and Susan M. Stocklmayer have described science communication as “the use of appropriate skills, media, activities, and dialogue to produce one or more of the following personal responses to science: awareness, enjoyment, interest, opinion-forming, and understanding”. It is important that different groups of the public engage each other in the arena of science communication, including the scientists themselves, decision-makers, media representatives and, undeniably, also people who do not specifically work in science, politics or media yet are interested in science.[1]

How it feels to be Inside you. Photo: Mariona Baltkalne

Science centres and museums, including anatomy museums, can function as a bridge or even a starting point for developing enjoyment of, or interest in, science. At the same time, it is possible to introduce another element into the museum collection that can help evoke the above-mentioned reactions or enhance them. Forms of artistic expression, for example, dance or music, can serve as such tools and are successfully being used to communicate current issues in science. The collection of the Rīga Stradiņš University Anatomy Museum has been enhanced by visual art – the ceramics intervention Foetal Attraction by British artist Paddy Hartley. Since the official opening of the museum in summer 2021, encounters between art and science have already taken place: the exhibition Anatomy and Beyond; the heart anatomy embroidery workshops Adatomija; and organ drawing lessons. Paddy Hartley’s work creates a new interaction between science and art, and although explaining science and, more specifically, anatomy is not the goal of this exhibition, it cannot be denied that almost one hundred ceramic figurines integrated into the anatomy collection form a connection with the permanent exhibits and allow them to be seen with new eyes.

Class of the Binewski Fabulon, Foetruvian Man and Jēkabs Prīmanis’ series of photographs with facial expressions taken in the 1930s. Photo: Mariona Baltkalne

Jēkabs Prīmanis (1892-1971), the long-time head of the Anatomy Museum, has also contributed to science communication and, one might also say, the promotion of science. Photographs taken in the 1930s with the professor’s various facial expressions demonstrating facial muscles are testimonies to a creative technique that was used in teaching anatomy to students. These photos are now a somewhat humorous exhibit in the museum’s collection and allow visitors not only to wonder at the number of muscles involved in making facial expressions but also to recall their own memories of pulling funny faces, grimacing or frowning. Paddy Hartley has also recalled memories of taking photos with his classmates in his high school days when it was often impossible to avoid laughter – and composing oneself in front of the camera was rather difficult. Thus, next to Jēkabs Prīmanis’ series of photographs, the artist has placed a group of figurines from the Foetal Attraction series called Class of the Binewski Fabulon.

Class of the Binewski Fabulon. Photo: Mariona Baltkalne

The name Binewski has yet another connection, which shows an essential feature of Hartley’s intervention – references to many literary and musical works and their characters. It more specifically refers to the 1989 novel Geek Love by the American author Katherine Dunn. It is a dark tale of Al and Lil Binewski, the owners of a travelling carnival who create their own unique family using insecticides, poison and radioactive substances. And here they all are – Binewski family members represented in ceramics, lined up just like before posing for a group photo and each of them trying to pull faces as much as possible. But while the Binewskis are preparing for the photo moment, the characters of the piece called Puttin’ on the Ritz seem to be awaiting Irving Berlin’s famous song (also used in Mel Brooks’ 1974 movie Young Frankenstein) to engage in a rhythmic dance with the adjacent exhibit – a human model placed in motion to demonstrate the musculature of the body. Watching this combination brings to mind Shawn Levy’s 2006 adventure comedy Night at the Museum in which the museum exhibits come alive at night. Perhaps the ceramic intervention also behaves in a different way during the night in the Anatomy Museum. Maybe it is an entire carnival, or perhaps a circus performance is taking place, because just like the travelling circus, Hartley's characters – with their beautiful face masks, red clown noses and paper bags on their heads – seem to be just stopping by for a while in the museum before moving on to another performance. Is the artist secretly a circus director? Perhaps; however, he has delegated this duty to Al Binewski who, after all, knows how to manage his big family and would surely know how to deal with the other circus performers as well.

Crosseyes the Clowns and their Juggling Jerkies. Photo: Mariona Baltkalne

There are two elements of the exhibition’s visual presentation that attract attention. First of them is, of course, the main character of the exhibition – a ceramic humanoid, a genderless creature called the foet. The Latin word “foetus” is also preserved in the title of the exhibition foetal, perhaps making some visitors wonder if they have read it correctly. For others, though, it might create interest – what is “foetal”? If one of the outcomes of visiting a museum is learning a new term in Latin, could it not be considered a successfully implemented science communication? But maybe foetal could also be read as fatal? Knowing Hartley’s great passion for literature and music, as well as taking into account the phrases and puns from the author’s native Yorkshire that permeate the works of the intervention, such a double meaning could also be plausible (not to mention it being reminiscent of film director Adrian Lyne’s 1987 psychological thriller Fatal Attraction). The second attractive element is the clear indication that the artist has created an intervention rather than a classic exhibition. If upon entering the museum one expects that the ambitious collection of Hartley’s ceramic works immediately await in a dedicated room, then it quickly becomes clear that it is not going to be as simple as that – a patient visitor will have to find, on their own, the many ceramic humanoids placed among the usual museum exhibits.

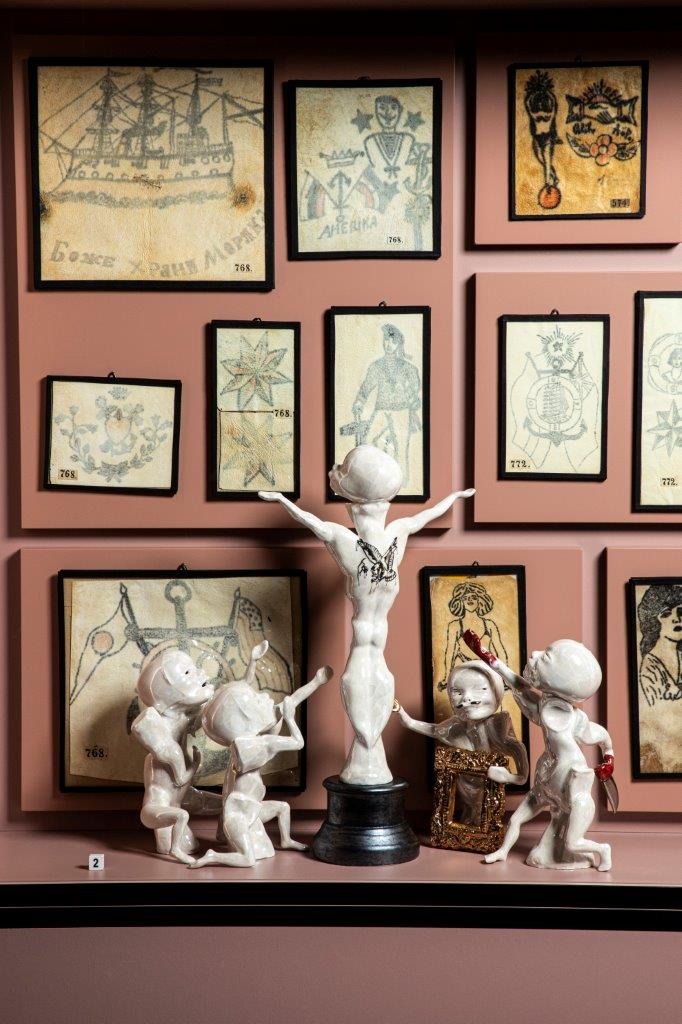

Skin. Photo: Rīga Stradiņš University

Humanoids interact with the museum’s space and the displayed collection so organically that in many cases they do not seem to appear as an attractive addition but rather as a necessity, for example, when appreciating the impressive size of a whale’s vertebra (the piece called The Nightmare Brothers) or the decorative shapes and textures of skin tattoos (Skin). Such an approach brings to mind the exhibition Art is Therapy organized in 2014 at the Rijkmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The writer and philosopher Alain de Botton attached large yellow notes throughout the museum that asked questions about art, inviting the visitor to think about why exactly this painting is considered a masterpiece and encouraging them to also pay attention to those works that probably do deserve the same recognition but are often ignored because they were not created by one of the “big” names in art history.[2]

Little Heartbreaker. Photo: Mariona Baltkalne

Hartley’s works of intervention also invite one to take pause. Both Heartbreaker and Little Heartbreaker remind the viewer that their heart and circulatory system have been traumatized by emotional experiences during their lifetime, just like with a heartbreaker’s hammer. One of the figures of the piece Can I Touch It? gently touches a corrosive specimen that belongs to the museum’s most fragile collection. The story of fragility is continued by the second character of the piece, who tries to touch the glass much more forcefully, reminding us how many of us have had the desire to do the same in museums but were never allowed to – someone would have reprimanded us. With puffed-out cheeks, The Pushovers are trying to push forward large human organs and bones with their hands and even their feet. “You are heavy!” is what one of the foets might be thinking, whereas Foamy Ass or Spongepants SquareBob and Patrick Star suggests the similarities between Spongepants’s shape and human lungs.

The Cooo-eeee's. Photo: Mariona Baltkalne

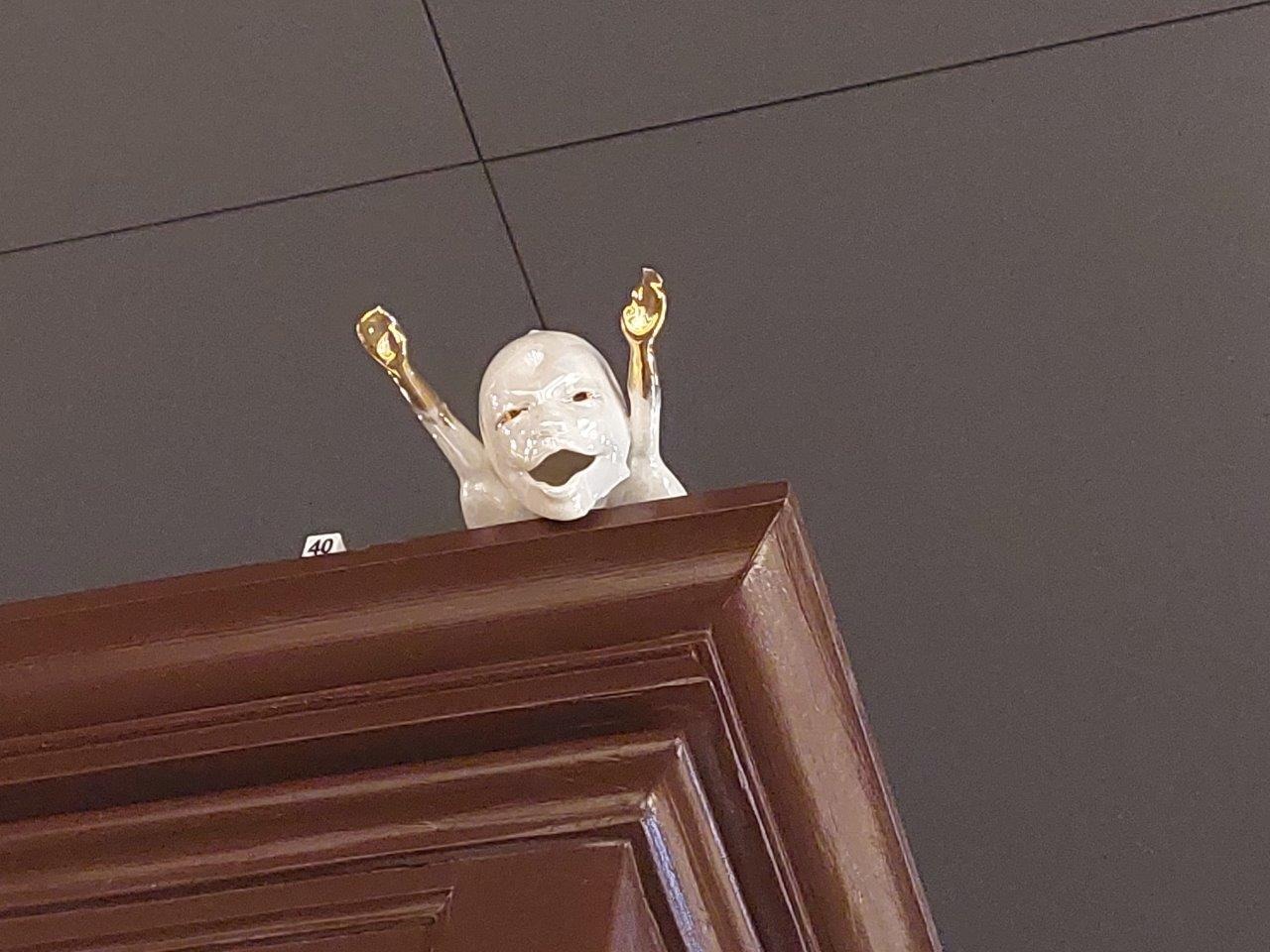

The beginnings of ceramic humanoids, or foets, in Hartley’s work date back to 1998, when he developed his master’s thesis in Cardiff, Great Britain; since then he has created several interventions. In 2022, Hartley responded to an invitation by Juris Salaks, the director of the Institute of the History of Medicine in Latvia, and created a series of works called Foetey Boys, which can be found throughout the museum’s collection. The foets can be found in very different places – some next to the anatomical specimens in easily accessible spots, while others have crawled atop a cabinet and would definitely call out “Peekaboo!” (or “Cooee”, if you’re in Yorkshire) if you only looked up. Some of them apparently want to have their own space, so they indulge in their deeds and mischief in the museum’s depository, where the visitor cannot get very close to the specimens and has to look very carefully to spot them. Another foet has crawled into a drawer next to the collection of temple bones and does not even mind that it will be noticed only if the drawer is pulled out. For ethical reasons, foets cannot be found in the teratology and embryology collections.

*Welcome! *all donations. Photo: Mariona Baltkalne

Hartley’s works are filled with playfulness and humour, but another inspiration for his works after an earlier visit to Riga is the statement “differences are normal”. Hartley keeps coming back to this statement, saying that we should be delighted about differences being normal because we are all so different. When it comes to people with functional disabilities, he points out that our world is simply not set up in a way for us to see these “disabilities” as a completely mundane difference. Therefore, we should not talk about people with any “special” needs. Hartley achieves variation in his foets by using the casting technique, but then deliberately influencing the process so that the foets’ faces, heads and body parts change their shape and become twisted.[3] Another mention of Katherine Dunn’s novel Geek Love is justified here as it speaks very directly about the variations and differences of the human body that are transformed from seeming defects into effects. The children brought up by the Binewskis are specially created to be different so that they can participate in entertainment shows, while the so-called “normal people” – those with a head, a body, two arms and two legs – are considered inferior in the novel because they are not so special or different.

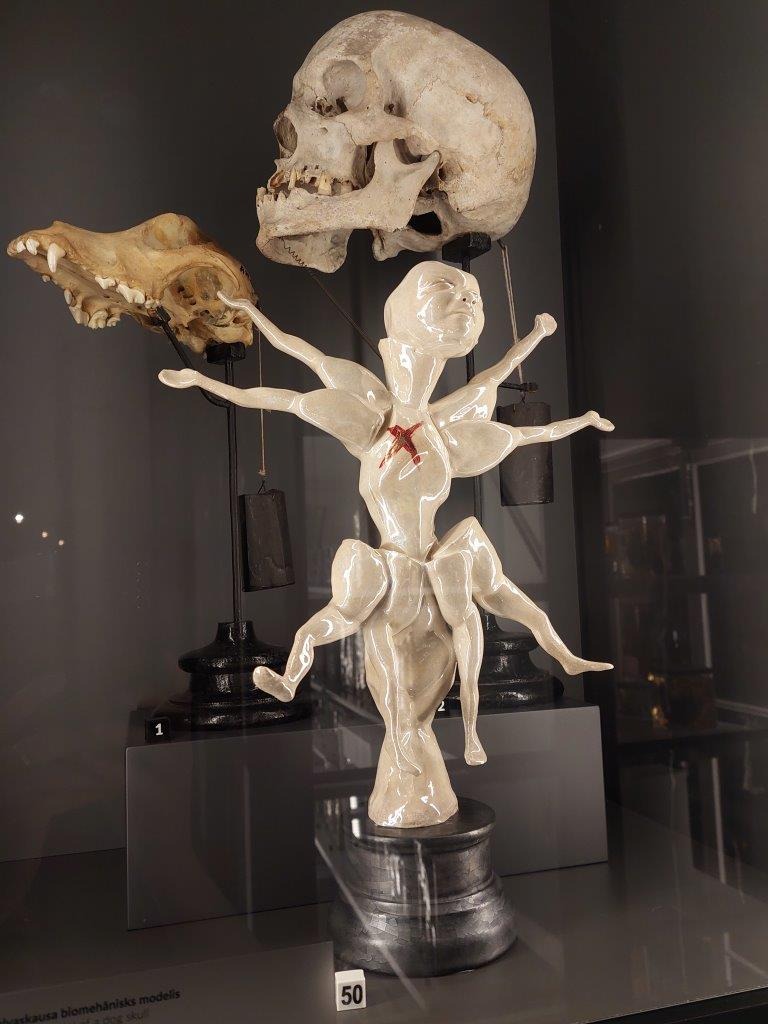

Foetruvian Man: Homage to Leonardo da Vinci's 'Proportions of a Man according to Vitruvius'. Photo: Mariona Baltkalne

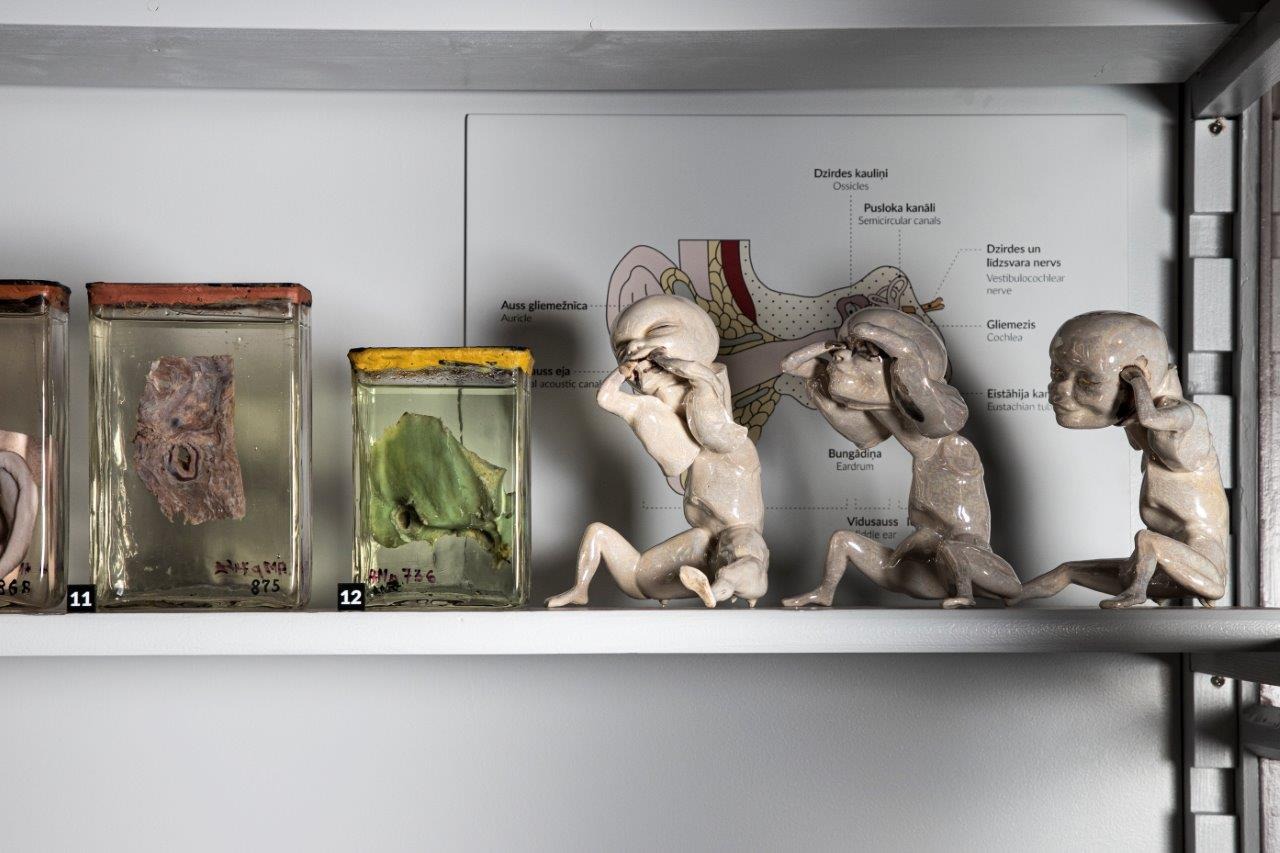

Hartley has also created several variations of Leonardo da Vinci’s well-known drawing The Vitruvian Man, this way again linking art with science and medicine and emphasizing the magic of difference. Da Vinci – a Renaissance man – highlighted the proportions of the human body in this work. Hartley has continued this idea by giving foets’ bodies more arms and legs and consequently naming them The Foetruvian Man. It might be difficult to figure out the progression of the number of legs and arms in the different versions of Foetruvian Man, but the correlation between the increase in its number of legs and arms and the variations of the titles of these “foetruvian men” is clearly noticeable. There is Foetruvian Man with four arms, four legs and one head, and there is also Ffooeettrruuvviiaann Mmaann – with eight arms, eight legs and two heads. But there are even greater variations on the theme: a foet with four arms, six legs and two fused heads. This seeming harmony of even numbers is suddenly disrupted by Binewskian Man or Al Binewski’s Rose Garden, which has seven legs and five arms. Because the differences are normal and beautiful, you can already imagine a smile on the artist’s face when trying to tell someone diligently counting the arms and legs that there is no need to stick with mathematical regularities here. But if the sheer number of arms, legs and faces start to feel like too much of a game at some point, Hartley’s commitment to his convictions, and simultaneously, his respect for distinct characters, is reflected in the piece that is a tribute to the artist Minnie Woolsey or Koo-Koo, who had Virchow-Seckel syndrome – a rare hereditary disease characterized by, among other features, a narrow bird-like face with a beak-like nose. This is represented through the foets’ clownery with bird beaks, but it is also a celebration of Minnie’s life. After all, while the Binewskis were still creating their own children who would later take part in circus performances, Minnie had already done many performances in her lifetime. The group of foets in the piece Hear No, See No, Speak No makes one think about how different people (in the official terminology – people with functional disabilities) reflect both Hartley’s concept of art and anatomy. Does anyone help conjure up a picture of the fragile corrosive specimens? Who hums the tune of Puttin’ on the Ritz, and how?

Hear no, See no, Speak no. Photo: Rīga Stradiņš University

It is difficult to discern specific thematic threads in Hartley’s intervention. One impulse leads to another, and so on. It is the artist’s creative journey from personal memories to a circus festival, with a medical history stop along the way while listening to the song What’s in My Head by the band Fuzz. Then one of the passengers on this journey makes amusing Yorkshire puns to pass the time, while another one responds by sharing a few Latvian idioms, such as someone having a “sharp tongue”, that is, someone who doesn’t hold back harsh words and can hurt others with them. The traveller Hartley imagines that the tongue literally penetrates someone’s brain. Suddenly, he has a flash of thought about “mentats” – creatures that do not need to penetrate somebody’s brain because with their superior brains they can already read the thoughts of others. Such mentats are described by Frank Herbert is his novel Dune. The traveller has also brought Roald Dahl’s story Skin with him, in which the original value of a tattoo on the main character’s back becomes much higher once a proposal is made to place the tattooed skin in a museum. (The same is happening with works by the street artist Banksy – his works are regularly cut out of the buildings on which they were created, leaving symbolic scars but also gaining more value in a gallery or auction house.) While reading the book, the traveller falls asleep; in his dream, apparently under the influence of Dahl’s story, a father figure appears – with a tattoo on his back. When the dream ends, so does the journey, and at the last stop, Hartley himself becomes the head of the circus festival. He selects the Anatomy Museum in Riga as the arena for the performances, and while the memories of what happened on the way are still fresh in his mind, he tells the story to the museum’s visitors. “Welcome!” says one of the foets to those who have entered the exhibition, urging us to look into this kaleidoscope and see reflections of cinema, paintings, songs, history, and even everyday life… Foetal Attraction undoubtedly captivates and invites one to explore more – to read, listen, watch, and learn. And that’s plenty for one exhibition.

Artist Paddy Hartley. Photo: Rīga Stradiņš University

Foetal Attraction by Paddy Hartley at the Rīga Stradiņš University Anatomy Museum, from August 18 to January 26

***

*Mg. Art. Journalist of the Public Broadcasting Company Latvijas Radio

[1] Burns, Terry W., O’Connor, D. John & Stocklmayer, Susan M. (2003). Science Communication: A Contemporary Definition. Public Understanding of Science. Vol. 2, Issue 2, pp. 183 – 202. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625030122004 [accessed 30.10.2022].

[2] Silverstone, Tom (2014). Alain de Botton guides you round his Art is Therapy show – video. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/video/2014/apr/25/alain-de-botton-art-is-therapy-rijksmuseum-amsterdam-video-guide [accessed 30.10.2022].

[3] Hārtlijs, Padijs (2022). Anatomijai un cilvēka ķermenim veltīta izstāde Anatomijas muzejā un Mākslas akadēmijā. Intervē Mariona Baltkalne. Zināmais Nezināmajā. Latvijas Radio 1. 26.09.2022. Available at: https://lr1.lsm.lv/lv/raksts/zinamais-nezinamaja/psiholingvistika-ko-krasa-dzimte-un-laika-lietojums-valoda-stast.a166201/ [accessed 30.10.2022].