One Must Imagine Ouroboros Feeling Good

Rosana Lukauskaitė

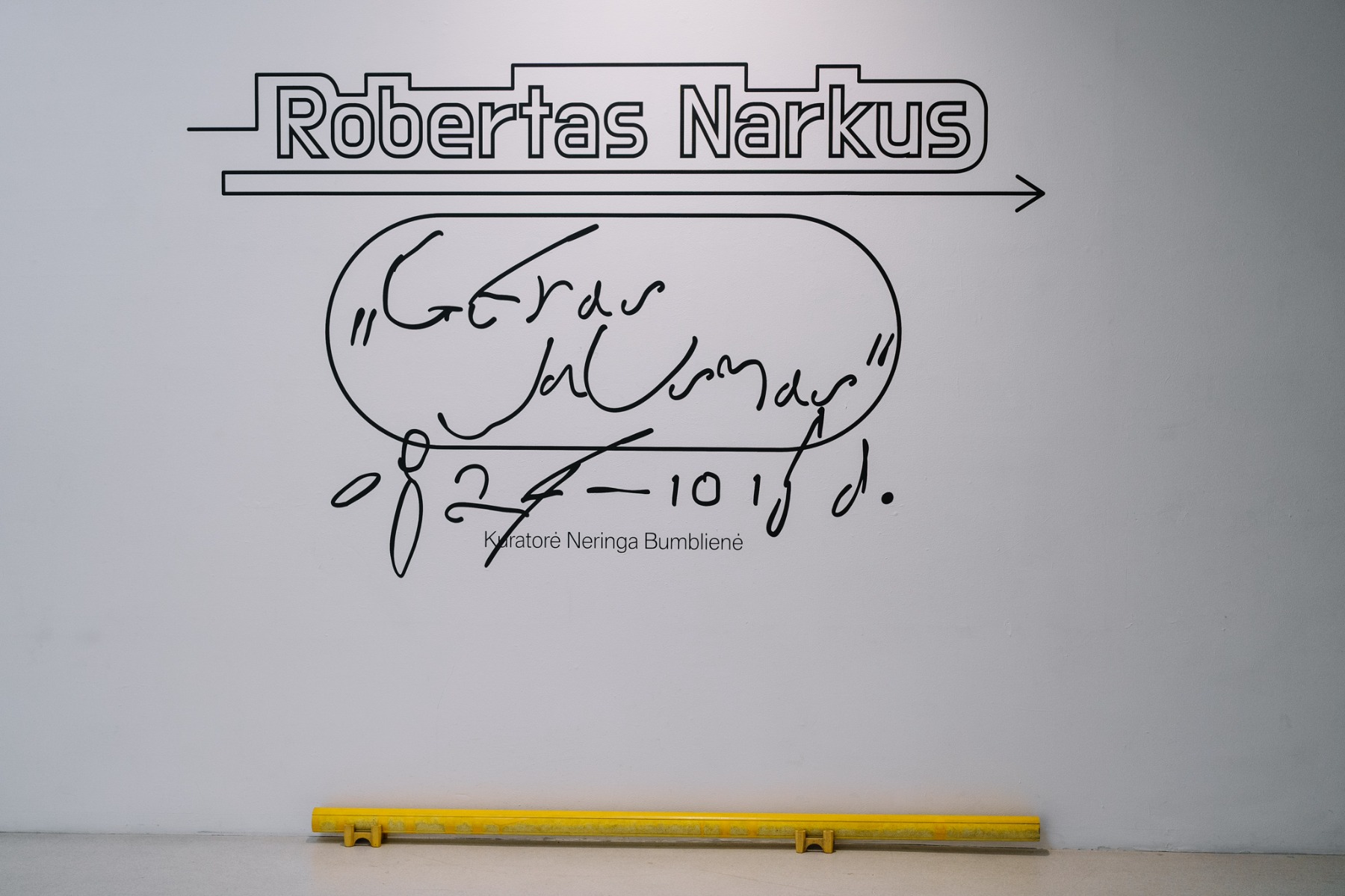

Review of Robertas Narkus exhibition at the KCCC Exhibition Hall in Klaipeda, Lithuania

I once had a dream in which I found myself in a hybrid city. This unique metropolis seamlessly melded Klaipėda (Lithuania) and Venice (Italy). The canals of Venice intertwined with the streets of Klaipėda, creating a mesmerizing blend of cultures and architectures. One might joke that after a heavy rainfall, the streets of Klaipėda indeed bear a resemblance to the canal system of Venice. However, I believe some of these similarities aren’t strictly tangible. Instead, it’s a more intuitive connection – perhaps a latent anxiety stemming from concerns over climate change or the effects of globalism seeping from the subconscious.

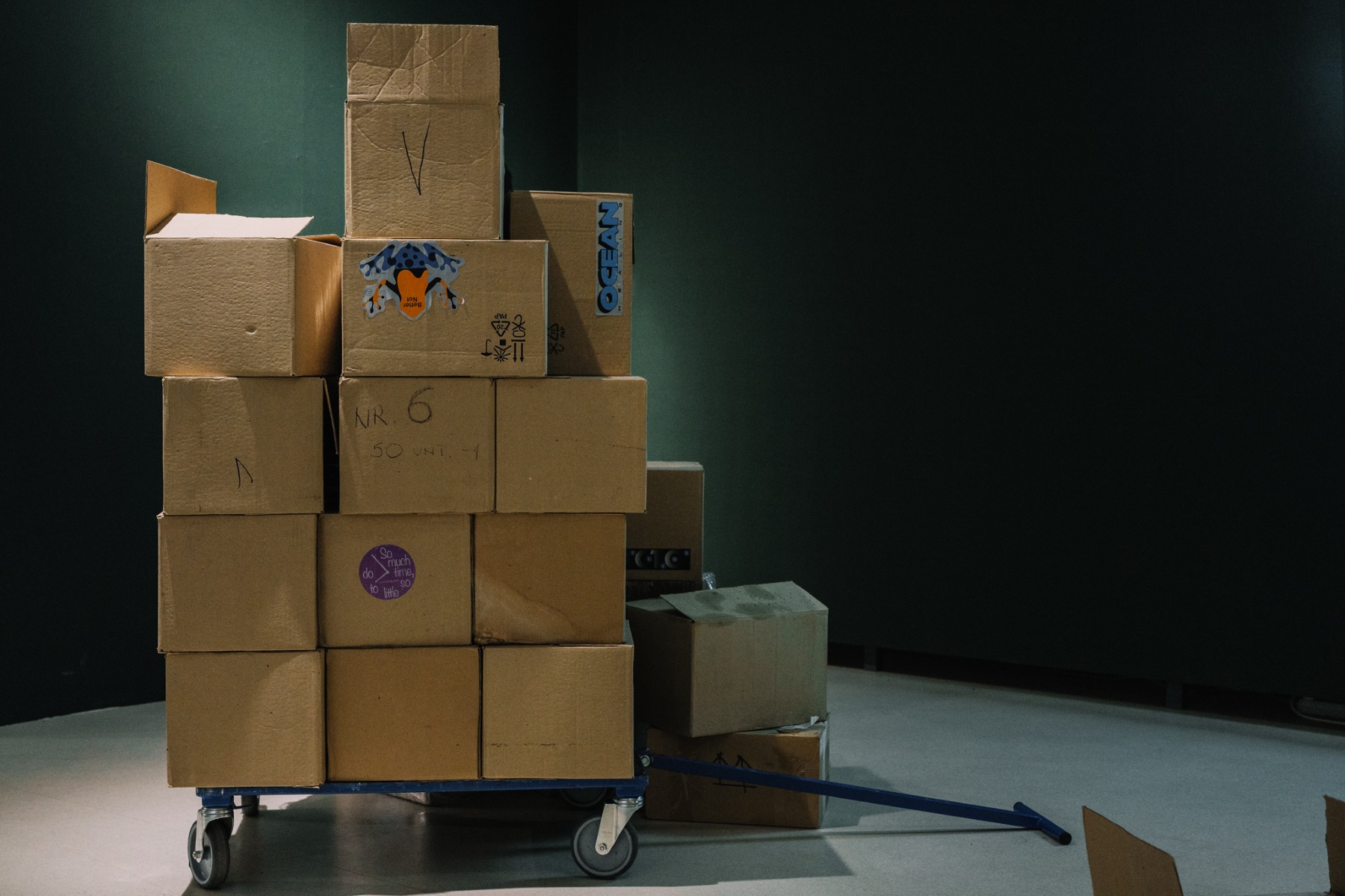

“Good Feeling” by Robertas Narkus at the KCCC Exhibition Hall in Klaipeda. Exhibition views. Photos: Domas Rimeika

I was reminded of this dream during my visit to the exhibition “Good Feeling” by Robertas Narkus at the KCCC Exhibition Hall (Klaipėda, Lithuania). Curated by Neringa Bumblienė, the exhibit will be on display until October 15. This is the first presentation of Narkus’ work on such a scale and scope in Western Lithuania featuring his latest pieces. The exhibition builds upon the concepts introduced in “Gut Feeling”, which was showcased at the 2022 Lithuanian national pavilion during the 59th Venice Art Biennale. The Klaipėda exhibition represents the third iteration of this project, with its title evolving from “Gut Feeling” to “Good Feeling”.

In his own words, while crafting his exhibition, Robertas Narkus grappled with diverse manifestations of fear. Chief among these was the trepidation of acknowledging our imperfections and our ceaseless compromise with a tainted environment. Yet, we often experience a profound sense of assurance, that comforting “good feeling”, when we make decisions that might seem counterintuitive. The exhibition unfolds like an onion, each layer meaningful and interconnected. It mirrors an obscured realm, a continuous contest for attention standing as a metaphor for our society’s ongoing struggle to define progress and where to focus our energies. The display conjures the imagery of a production line, hinting at manufactured solutions to society’s pressing concerns.

The exhibition highlights seaweeds, specifically the canned Undaria pinnatifida, originating from Asia. However, with globalization, these seaweeds have found their way into Venice’s canals. Packed within the cans of the installation “Gut Feeling Can Conveyor” lies the promise of a universal remedy – a solution to issues ranging from aging to nutrition. But there’s a twist: while Undaria pinnatifida might be hailed as nutritious, it has burgeoned as an invasive species in Venice. Moreover, the pervading toxins in the environment, which are readily absorbed by the seaweed, deem it unfit for consumption. This begs the question: How often do we ingest harmful substances while rationalizing them as necessary? It has become commonplace to take supplements before consuming fish in anticipation of the toxins they contain. Reports of microplastics in placentas no longer shock us, which in itself is a testament to our desensitized response to alarming realities. This raises the question: At what point does the filter intended to shield us from toxins become indigestible itself? We’ve heard about larvae that consume plastic, but as we move towards incorporating worm protein into our diets, how will these phenomena overlap? This potentially leads us into a complex terrain where the lines between the consumer and the consumed blur, inviting us to ponder deeper on the cyclical nature of life and our sustainability choices in a rapidly changing ecosystem.

This conveyor can also be seen as a manifestation of the Ouroboros – the ancient symbol of a serpent consuming its own tail – which represents an eternal cycle of creation and destruction. Such a loop in which rebirth arises from demise raises contemplative questions about its possible manifestation in human society: Could we, at some juncture, turn inwards and begin committing acts of auto-cannibalism? Minor acts of self-harm often seen as innocuous or nervous habits – like picking at a scab or chewing one’s inner lip or nails – hint at this inward focus. On a more controversial front, some celebrities promote the benefits of creams derived from the foreskin of newborn male infants, thereby tapping into what could be considered a cannibalistic inclination. While such practices may seem modern or avant-garde, their roots might trace back to ceremonial funeral rites of ancient cultures in which consuming the deceased was both an honour and a way to absorb their essence. Even in religious contexts, there are echoes of this sentiment: “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life”. It’s an intricate dance of beliefs, ancient rites and modern practices that challenges our perceptions of consumption and reverence.

The exhibition also delves into the realm of contemporary “mythology”. The artist introduces painted stainless steel objects that echo visual elements from the Google Docs application – icons and tools typically employed for designing diagrams, charts, and spreadsheets that project profits or losses. In a subtle act of subversion, these ordinarily sterile and transactional icons become humanized: they’re artfully arranged to evoke the semblance of a smile, reminiscent of the face pareidolia phenomenon. This reimagining hints at a world where even the coldest digital tools, when reframed, can mirror our innate human need to find familiarity and warmth, suggesting that our emotions often intersect with technology in unexpected ways. However, an underlying tension pervades this apparent whimsy. Can a smiley face mask more sinister intentions? Perhaps beneath those spreadsheets lie calculated conscious wrongdoings, environmental harm, or other transgressions that we may struggle to confront. The juxtaposition of innocuous symbols with potential malevolence challenges viewers to question the deeper narratives that lurk behind the mundane.

Displayed in the exhibition are also photo collages depicting life-size objects from the artist’s studio – tools and materials that are commonly associated with construction and production. This representation mirrors a broader societal observation: the way we interact with resources, both tangible and intangible. Most contemporary video games centre on the theme of gathering resources and personally utilizing them. This gameplay mechanic is not merely an entertaining diversion; it signifies a deeper societal sentiment. The idea of directly benefiting from one’s own labor has become so alien to many in modern society that it has transformed into a form of escapism through these virtual worlds. Engaging in such activities within a game offers a dual experience – it’s not only a nostalgic nod to a perhaps simpler, self-sustaining past but also a cathartic regulation that allows players to find balance and satisfaction in an environment they can control, and it draws a stark contrast to the complex, often impersonal realities of the modern world.

In expanding upon this theme of resource interaction and personal utilization, the exhibition further pushes the boundaries of representation and reflection. Screens showcase a video piece titled “Directed Evolution” in which viewers witness a man immersed in a bathtub brimming with kelp. This man is none other than the globally renowned chef and food scientist David Zilber, who brought fermentation to the forefront in the West. He delves into a monologue, occasionally veering into intricately complex terminologies, articulating how everything in existence is interconnected. He speaks of minuscule bacteria that, when translocated to a distant part of the earth, can profoundly alter the lives of not just humans, but myriad forms of life. He says, “Lest we forget, however, that the chief mechanism of evolution is extinction”. David occasionally repeats his lines and this provides a raw, unedited glimpse into the “kitchen” of this artistic creation. Shot in an apartment in Venice, the video also captivates with its recurring motif of an inflating and subsequently bursting bubble – a symbol that resonates repeatedly throughout the exhibition.

The bubble emerges as a potent symbol, representing structures and entities to which we, perhaps mistakenly, grant overwhelming power. It serves as a poignant reminder that we often neglect our own voices, our own agency, hesitating to believe that we, too, can enact change. Bubbles are ubiquitous in nature and manifest in myriad forms. They appear when ocean waves crash or when raindrops splatter. They can be found in volcanic rocks, evidence of the molten fury from below, or trapped in layers of ancient ice. In a broader sense, Earth’s protective atmosphere could be likened to a grand bubble, enveloping us in its life-sustaining embrace. Yet the inherent fragility of bubbles serves as a poignant reminder. They remind us of the delicate balance in which our environment teeters, and how easily disturbed equilibria can result in profound changes. Sadly, as with all bubbles, there’s an inevitability to their rupture. In pondering the universe’s beginnings, one can’t help but wonder: Was it the Big Bang, a moment of explosive creation, or perhaps a “Big Bubble” – a vast expanse that reached its limits and burst forth into existence?

At the end of the day, “Good Feeling” is something we brew and ferment within ourselves, a concoction of our experiences, hopes, and uncertainties. While the transition from a gut feeling to a settled good feeling is nebulous, it’s deeply intertwined with our psyche’s ability to process, accept, and transform. Perhaps one must imagine Ouroboros feeling good.