Sisterhood of Monsters

Sofia Dati

Excavating the demons of Modernity

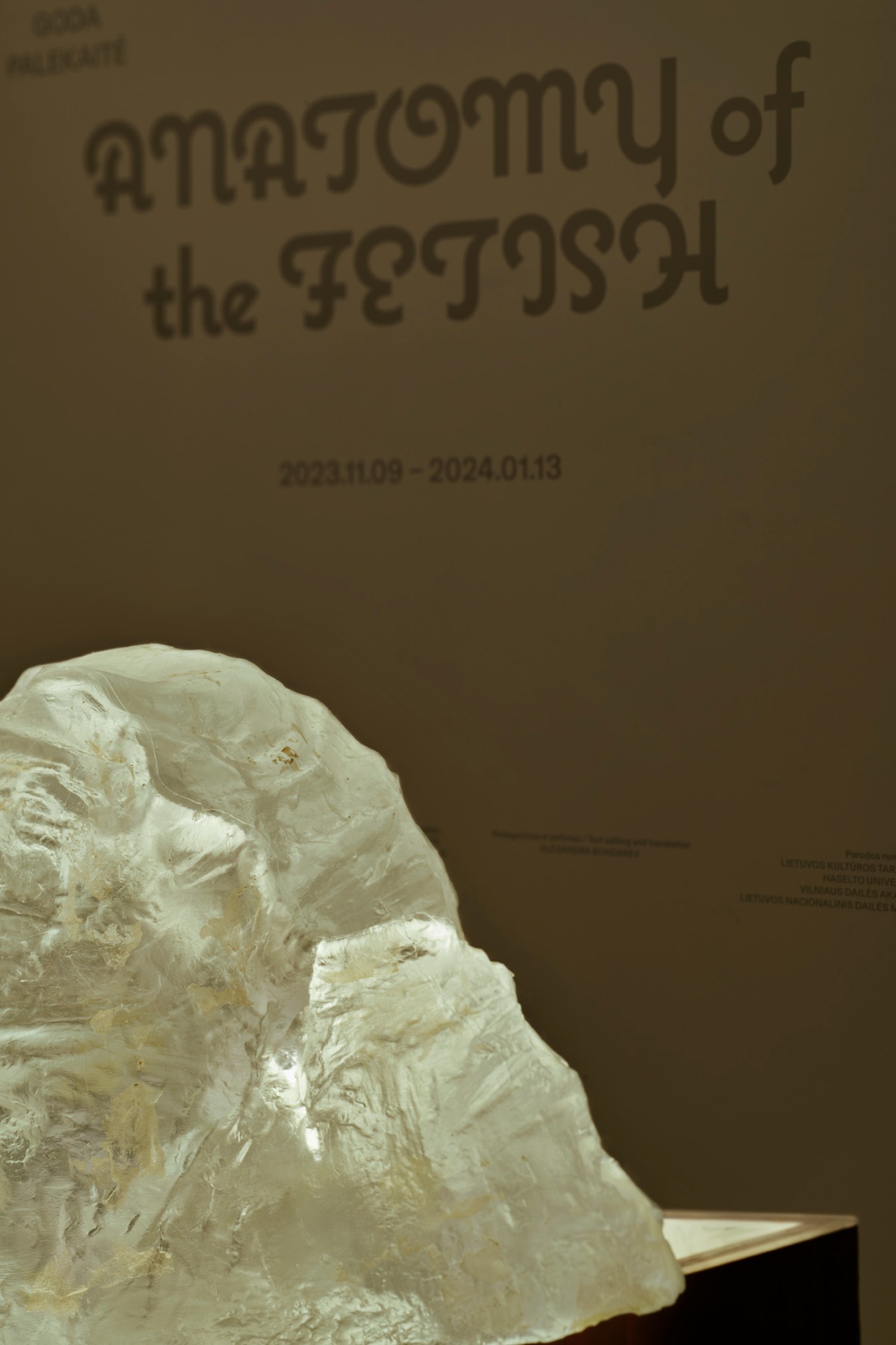

Anatomy of the Fetish invokes the entangled strands of history contained in the travels of the word fetish through time. From a latin term referring to the artificial, the factitious or the object of art, fetish landed in Portuguese language and culture in the Middle Ages. It then signified sorcery or witchcraft, as a way to describe objects of devotion encountered in the course of Portugal’s expeditions through the Western coasts of Africa. In the exhibition, Goda Palekaitė and Marija Puipatė excavate layers of flesh and cultural biases related to (mis-)conceptions of the fetish, previously known as facticius, or feitiço.

***

Anatomy of the Fetish. Exhibition at the Vartai gallery. Photos: Darius Petrulaitis

The fetish traverses histories of oppression and repression towards those who are othered because they are alien to the ruling orders of patriarchy and Empire. One such othered figure was assembled in the form of the Orient: an imagined space dreamed up by Western imperialist and colonial fantasies. The first character that we encounter in the exhibition is a man who expressed his fascination for Eastern cultures, Islamic and Sufi belief systems, as well as anarchism. In his painting The City in the Hills (Egyptian Landscape), Swedish orientalist artist and writer Ivan Aguéli (1869-1917) portrayed a fortified city departing from the shore. A minaret is pointing to the sky and soft dunes surround the city walls. Yet, it is a very different landscape that Goda Palekaitė offers in response to Aguéli’s vision. Monotheistic Light (2023) is a miniature replica of a mountain in Sweden that Aguéli might have contemplated during his lifetime, when he was not traveling through Egypt, Sri Lanka, India or France. The mountainous sculpture depicts the painter’s romanticized idea of oriental mysticism. Adorned with light and star-shaped symbols, the piece displays the othering prism through which Aguéli approached a cityscape in Egypt, which could be drawn from places such as Heliopolis, Abydos, or perhaps Luxor, home to the temple of Amon.

Echoes to orientalism appear again in the next room, with references to the Luxor obelisks and the kitsch design of the parisian Louxor cinema. A pair of obelisks from the Egyptian city of Luxor came to the attention of Napoleon Bonaparte, one of France's fiercest conquerors, during his expeditionary campaign in Egypt and Syria (1798-1801). The campaign gave birth to the discipline of Egyptology, which was one expression of the then-trending phenomenon known as Egyptomania. It is a story of origins that gained much popularity in European and American societies. They wrote bestsellers, poetry and dissertations about the delightful mysteries of the exotic cradle of Western civilization – perhaps even of humanity itself. France had desired the Luxor obelisks since the 1800s. The dream first dreamt by Napoleon was realized by Charles X in 1830. That year, France was invading Algeria, and the 23 meters high sculpture gifted to the French king by Egypt’s governor Mehmed Ali Pasha was erected on Place de la Concorde. So the obelisk made its way to Paris, like innumerable other items that populate, to this day, European museums.

The Louxor opened its doors in Paris in 1921. Inspired by the Louvre’s Antiquity collections, the architects dressed up the cinema in an “Egyptian Revival” fashion. A fashion that Goda Palekaitė and Graham Kelly connect to fetishistic drives in their film Swallower of Shades (2023). They portray different waves of egyptomaniac fantasies expressed through films, museum displays, and (post)modern thinkers. Egyptomania performs a deep-rooted desire to possess, assimilate and anatomize an object of devotion and fascination; in other words, an other. Before Napoleon’s imperialist expeditions, this drive to ‘acquire knowledge’ paved the way for exploratory missions that led to the ‘discovery’ and exploitation of The New World.

***

The image of an exotic, lost civilization to be excavated made its way to the early stages of Modernity, with its pursuit of knowledge and its extractivist tendencies. The 16th century was a time in which cartography was booming, the first wave of European colonization was ongoing, and European scientists were drawing on the findings of Ancient Egyptian scholars to revive the discipline of anatomy and take on expeditions in the meanders of the human body. The exhibition recuperates this anatomical gesture that enthralled early Modern medicine, in a move to uncover layers of stolen history.

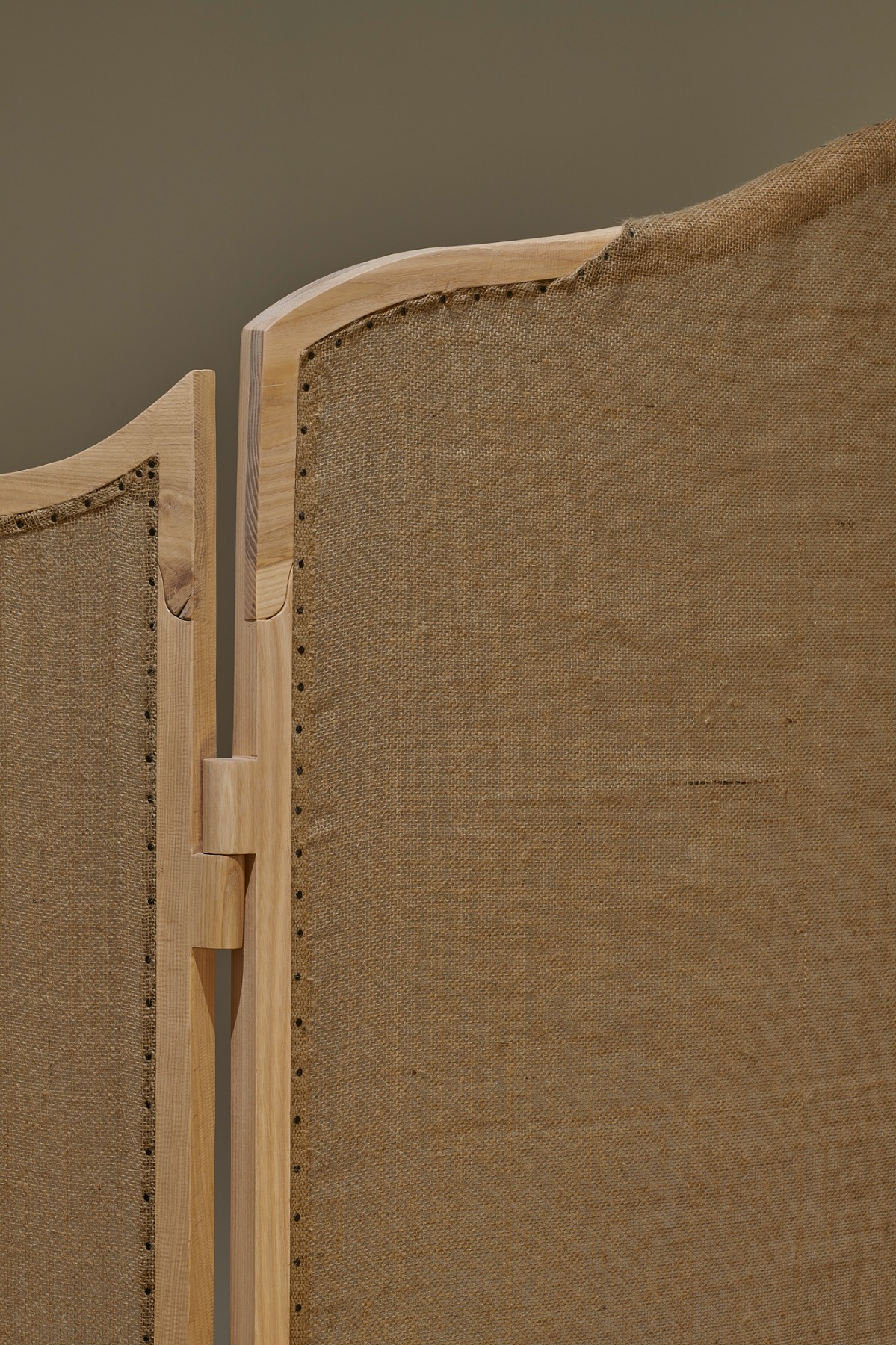

The bare, bouncy springs of Marija Puipatė’s Undressed Settee (2023) relate to the soft satin texture of Not Savonarola’s Chair (2023), in that both works explore the insides of furniture. The artist anatomically dissects the (re)forms and (mis-)uses of domestic and politically charged design objects. She turns their shapes inside out, shifts their scale and challenges their function. Not Savonarola’s Chair invites for ergonomic comfort on a seat linked to authority and aristocracy.

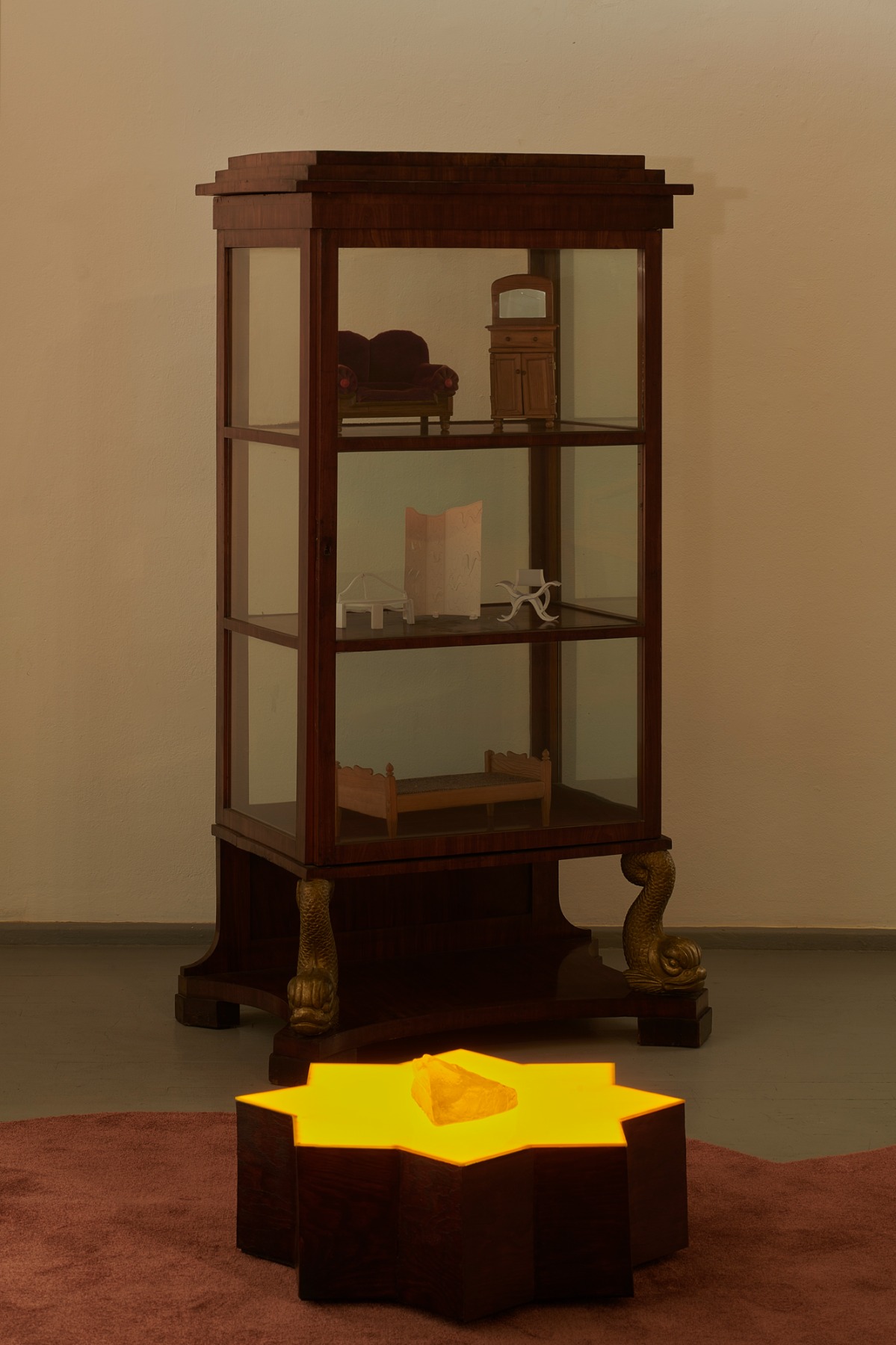

This type of chair came into circulation in Italy in the 15th century, although its criss-cross motif had been used before in thrones and other chairs designed to symbolize power. The chair’s name pays tribute to the Florentine theocrat Girolamo Savonarola, whose preaching for a simpler life supposedly inspired the design of a light and elegant chair. In Miniatures (2023), a tiny version of Not Savonarola’s Chair is neatly placed in an antique Empire-style vitrine (19th-20th century), next to miniature replicas of a bed and other furniture from the artist’s childhood home.

Memories of a Medieval noble interior cohabit with items from a post-soviet Lithuanian bedroom. This assemblage of disparate items and contradicting timelines challenges the nostalgic aspect connected to the fetish as a devotional object standing in for a lack. Instead, the artist seems to invoke the fetish as a space of memory that feeds into an unexpected transhistorical dialogue. The replica is Not the original: it refuses and exceeds the notion of lack. What is left is an uncanny translation of an absent past that keeps lingering like a ghostly apparition in the immanence of the present.

In the scenography, Barbora Šulniūtė also adopts a posture of unruly mimicry. Her spatial design summons up a dreamy image of Renaissance Venice, then nicknamed La Serenissima. The scenography simulates the feel of a lavish bedroom where a floor pattern interpreting a typical Renaissance Venetian ceiling mingles with the vanished history of an anonymous antique trumeau mirror (18th-19th century). An open window lets in a soft ray of light; and a bit further, on a star-shaped plinth, another mountain dedicated to Ivan Aguéli stands in as a bedside lamp (My Personal Sun, Goda Palekaitė, 2023). And another source of light emanates from Palekaitė’s and Puipate’s collaborative work Four Humours (2023), hanging like an ensemble of coloured street lights on the opposite wall. Palekaitė’s four organ-looking light sculptures are upheld by chair legs designed by Puipatė in a re-imagined Renaissance style. Each organ is associated with a different humour, which Medieval medicine believed to contain the vital bodily fluids whose balance determined one’s behaviour and health. Writers Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English describe this period of European medical history as a time in which “regular” medicine was grounded in religious belief and superstition; a time in which doctors spoke of temperament, good and evil humours. Yet, the establishment fought a ruthless battle against the knowledge and practice of those women who acted as the healers and obstetricians of the lower classes. Those women were called witches and were persecuted for their sorcery, magic and fetishistic practices.

***

Veronica Franco too, was tried for witchcraft. Palekaitė and Puipatė spent time with the archives of Veronica Franco, a renowned courtesan hailing from 16th century Venice. At the height of a four century-long witch-craze that traversed the whole of Feudal Europe, Franco was accused of chanting magic spells and engaging in heretic rituals. In Venice, the artists read correspondences and documents narrating Franco’s social ascension and downfall, her trial and her struggle against the demonization of female sexuality and self-determination. “Witches represented a political, religious and sexual threat to the Protestant and Catholic churches alike, as well as to the state.” As they represented a threat to the ruling class’ hegemony on healthcare and science, they were made into monsters – a most common practice that continues to be widely used for the sake of preserving dominant positions.

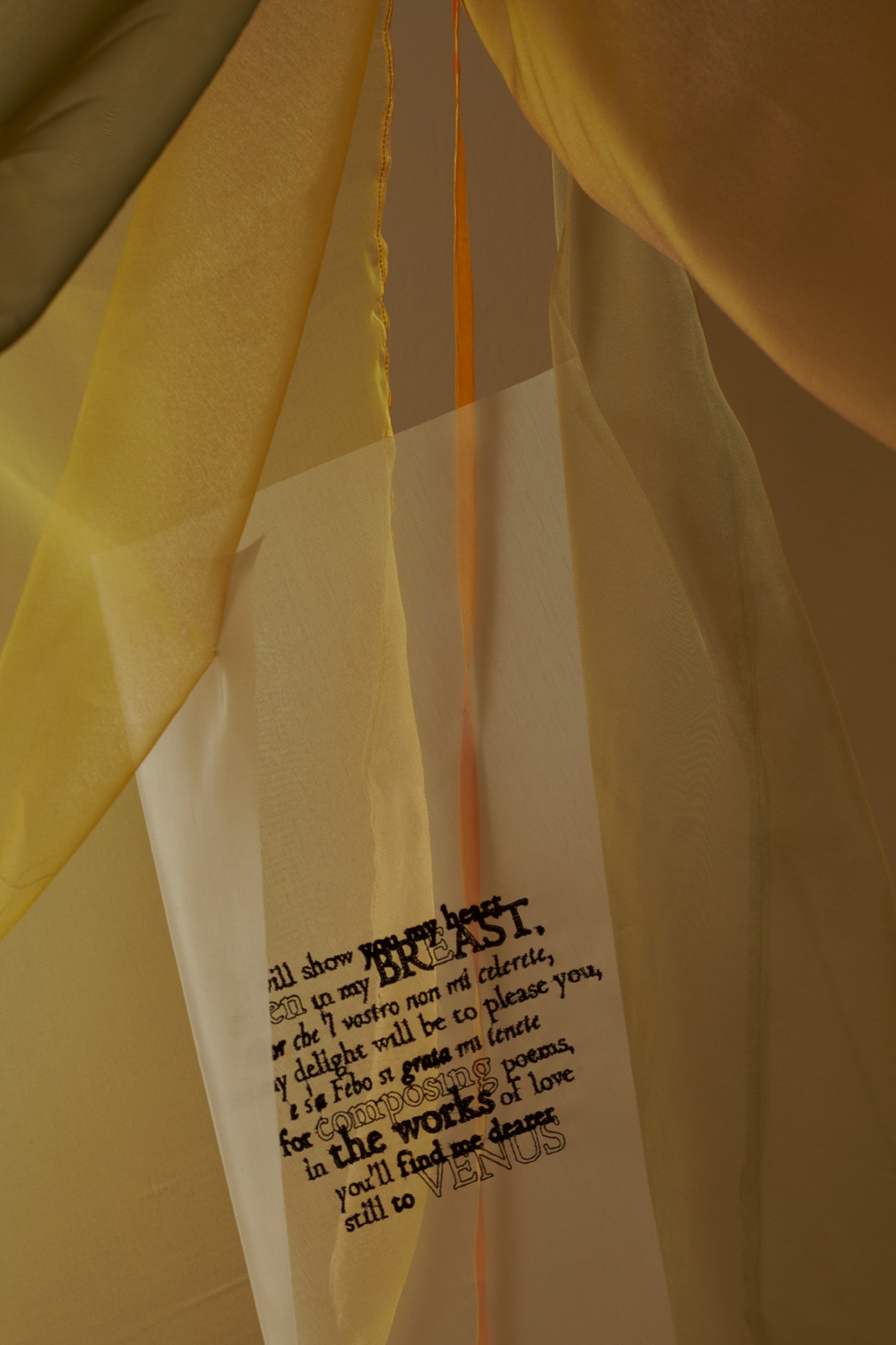

Floating at the center of the exhibition space, a baldaquin poses as Medusa, a mythological woman-monster who came to symbolize rape and danger (Medusa’s Baldaquin, 2023). Whispers emerge from inside her folds. The poems embroidered on the drapes of the baldaquin are premonitions of two soul sisters who lived a few centuries apart. Grisélidis Réal, like her far-away ally Veronica Franco, practiced sex work, painting, activism and writing.

“I was myself all the bodies of the other people who’d come here, I wasn’t only their body, but their penis, their soul, their race, I became totally multiple. You’re like a piece of algae tangled up in other algae. It’s an ocean”.

Réal’s ocean connects the shores of Luxor to Italy’s most touristic lagoon and Switzerland’s urban spaces in the 1970’s. It connects the struggles back then to the demonstrations today. From a historical leap to another, a new plot of alliances takes shape. The room’s decor unpacks the strangeness of a dream in which disjointed timelines intersect.