A Collection as a Library of the Human Condition

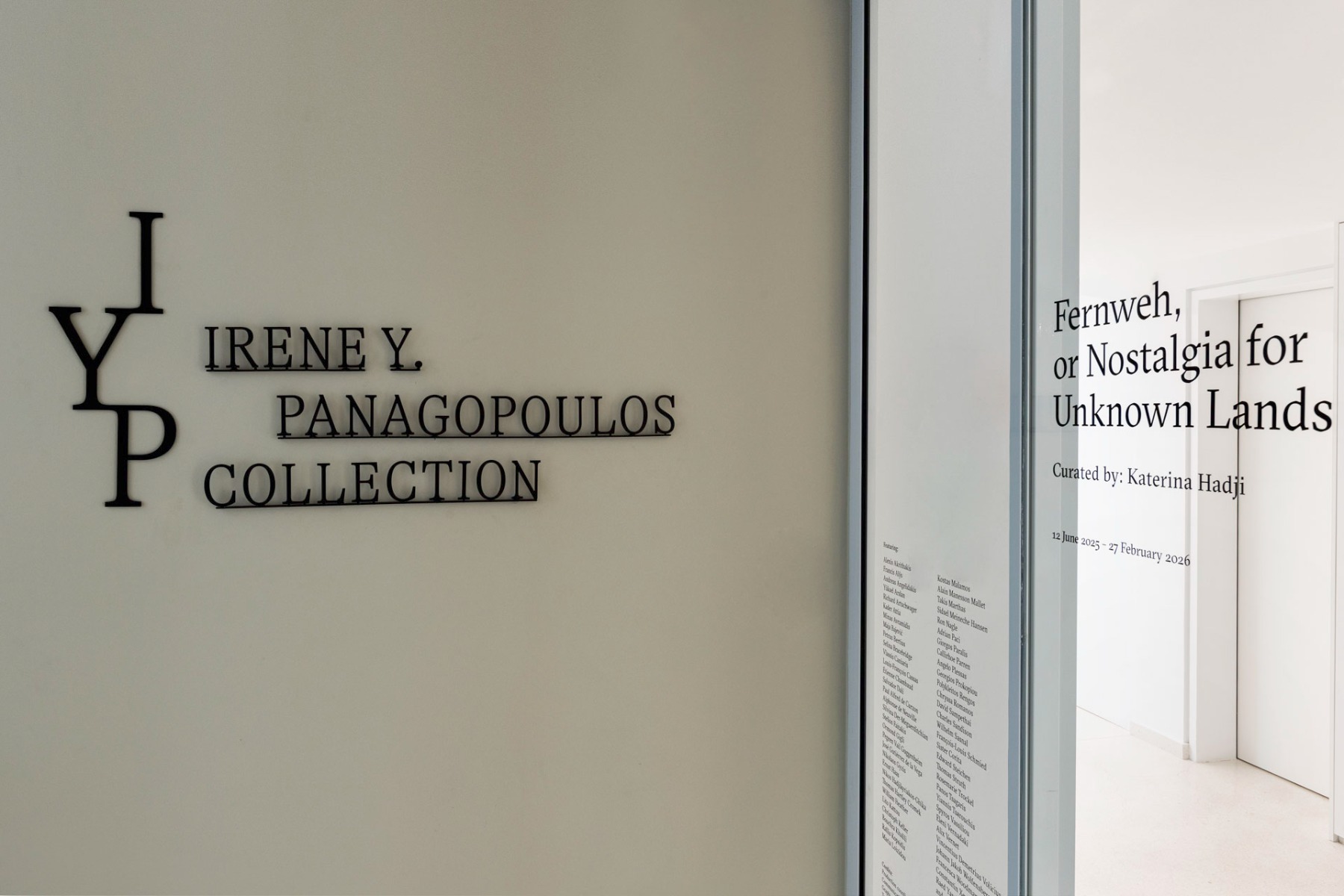

The group exhibition Fernweh, or Nostalgia for Unknown Lands marks the opening of the Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space in Athens

In mid-June, the Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space—a new initiative by the Greek collector and philanthropist—opened its doors in Athens with the exhibition Fernweh, or Nostalgia for Unknown Lands. Located on the second floor of the building that also houses her company’s offices, the space is arranged in a way that evokes a book or a symbolically open art repository—a kind of visual library.

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection. Photo: Nikos Alexopoulos

The debut exhibition quite literally invites visitors to peek into the repository—as if it had been symbolically opened—illuminating just a few pages of the collection while offering a glimpse of the library’s broader scale. At once a workspace, gallery, archive, library, repository, and site of preservation, the space encourages reflection, engagement, and discovery—intellectual, visual, and emotional.

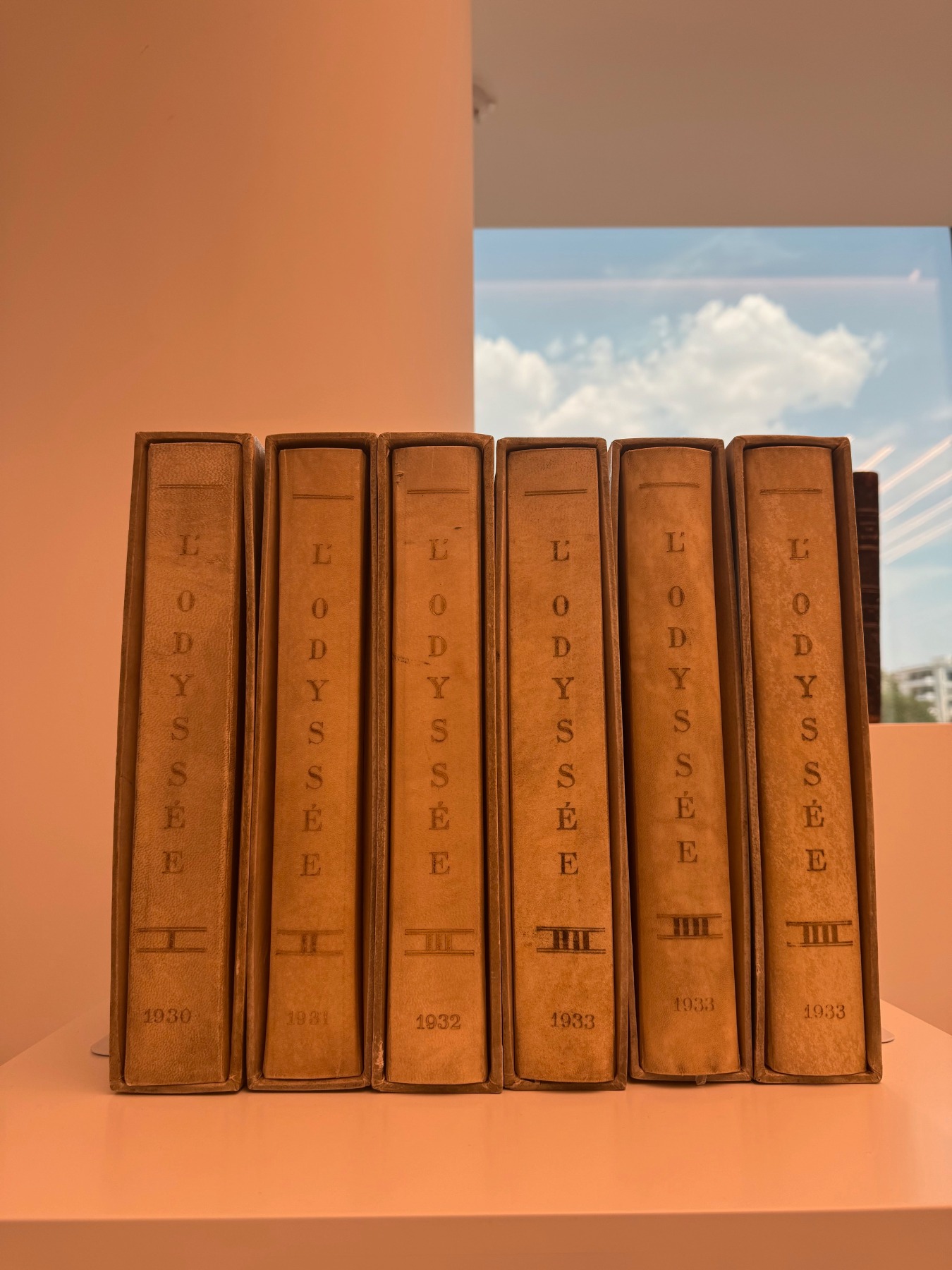

The scenography of the space also reflects the identity of the collection itself, which originally began with artists’ books. “For me, a book is multidimensional. I’ve always been fascinated by books as an art form,” Irene told me in an interview a little over a year ago. “Each page of an artist’s book reveals something new, making it a continuous work of art. There is a sense of motion and kinetic quality in a book that I find captivating.”

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Arterritory.com

Panagopoulos is the CEO of Magna Marine Inc., a dry-bulk shipping company founded by her father, Pericles Panagopoulos, who was also a collector. Collecting, therefore, is in Irene’s genes. Works from her father’s collection — which included oriental rugs, antique maps, and pieces by Greek artists from the 1970s and 1980s — formed the foundation of her own. From this seedling, Irene’s collection has continued to grow and evolve organically, gradually acquiring its own distinct identity. It takes a distinctly international approach, encompassing visual artworks, folk art objects, archival materials, books, manuscripts, maps, historical documents, and applied-artifacts — including works by established, emerging, and unknown creators.

Lito Kattou (b. 1990).Warrior III, 2017.Steel, car paint, aluminium, minerals, chains, plastic, 188 x 157 x 76 cm. Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection. Photo: Nikos Alexopoulos

“Art reminds us of our relationships, our identity, who we are, what we represent, and where we want to be. It highlights our connections and serves as a tool for communication. We need art because it reminds us of beauty and helps us see things more clearly. I believe that art is like a voice. And as a voice, it is often more powerful than words. It can also tell us who we are. It underscores that we are human above all,” says Irene.

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Arterritory.com

The show Fernweh, or Nostalgia for Unknown Lands, unfolds like a knot within a net of ideas, historical periods, and sociopolitical events, aspiring to illuminate some of the core themes of the Irene Panagopoulos Collection. At the same time, the exhibition offers a deeply personal interpretation of how we perceive the world and reality at a specific moment in time. It frames this perception as a continuous process of self- and world-discovery—one closely tied to the tools and knowledge available to us at any given moment. In this light, reality becomes an ever-evolving process of redefining and expanding the boundaries of what is known. It is no coincidence that the exhibition’s curator, Katerina Hadji, chose the German word Fernweh [fern (“far”) + Weh (“pain”), meaning “longing for distant places” or, loosely, “nostalgia for unknown lands”] to capture this deep and persistent yearning for exploration.

As Walter Benjamin writes in his essay “Unpacking my library”: “Property and possesion belong to the tactical sphere. Collectors are people with tactical instinct; their experience teaches them that when they capture a strange city, the smallest antique shop can be fortress, the most remote stationery store a key position. How many cities have revealed themselves to me in the marches I undertook in pusuit in books!”

Christoph Keller (b. 1967). Archaeology Plant Series (1–4), 2014,

1) Hephaestion, 2) Epidaurus Theater, 3) Olympeion, 4) Poseidon of Artemision

Pigment print on photo rag, 54 x 43 cm

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection. Photo: Nikos Alexopoulos

The exhibition, which is divided into five sections, symbolically begins with a return to the roots. Its first “chapter”, Romanticism – Greek Antiquity, centers on a myth that has remained remarkably enduring for centuries: the idea of Greece as “the cradle of Western civilization”. It presents Greece as a destination for physical or imaginary pilgrimage—a place sought out in the quest for meaning and inner fulfillment. Even when the encounter with “the beautiful and the sublime” is indirect, or ultimately revealed as a construct of the mind, the myth persists. The works assembled in this section offer a compelling perspective on how artists of various nationalities viewed Greece during that period—from the distinctly Orientalist motifs in a painting by Spanish artist José Gutiérrez de la Vega, to the emphatically Romantic landscape Landscape with a View of the Acropolis in Athens by Swiss painter Johann Jakob Wolfensberger (1797–1859).

The works often seem to engage in a dialogue, complementing each other and illuminating details that might otherwise go unnoticed. Louis-François Cassas’s (1756–1827) work Imaginary View of the Ruins of the Tomb of Antioch Philopappos in Athens depicts Philopappos Hill, which still holds a very special place in the symbolic landscape of Athens—not only for visitors to the city but also for locals. It is also known as the Hill of the Muses, named after a fifth-century BC sanctuary dedicated to the poet and prophet Musaeus. The Greeks believed the hill was inhabited by the nine muses and that Musaeus, a poet and disciple of Orpheus, was buried there.

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Arterritory.com

Nearby is a watercolor by British painter Thomas Hartley Cromek (1809–1873), entitled Acropolis, which notably depicts camels among other elements. According to historical records, camels were indeed present in Athens at that time. Meanwhile, an anonymous 19th-century drawing titled Greeks Fleeing the Burning shows people escaping from a burning city. Interestingly, this is not the only anonymous work in Irene Panagopoulos’ collection, which resembles a puzzle connecting the known with the unknown, thereby continuing to weave the fabric of a multifaceted reality.

For example, the exhibition also features the work of Greek artist Alexis Akrithakis (1939–1994), No II – Le Feu – Hommage à Georges Makris (1968), dedicated to the obscure poet and intellectual of his time, George Makris. Makris published a pamphlet entitled Proclamation No. 1, calling for “the complete destruction of all classical monuments, starting with the Parthenon.” The text argued that monuments like the Parthenon—long idolized as national symbols—had become oppressive archetypes, trapping modern Greeks in inherited ideologies, tourism, and past glories. As Greek curator Marina Fokidis writes in South as a State of Mind: “Suggesting the destruction of one of Greece’s most important and treasured historic sites seemed like a completely non-patriotic, immoral and transgressive gesture; however, it captured the interest of several marginal intellectuals who most probably found in it a refuge from the tyranny of history and the absolutism of various ideologies. It was neither a manifest nor a set of guidelines for a violent act, but more of an artistic/performative text signalling a desire for the liberation of sacred archetypes that could easily be – and were – abused so as to serve conflicting purposes and propagandas.”

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Arterritory.com

Right next to it is a truly unique work by Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), Athena (1965), which depicts the birth of Athena in a surrealistic manner—the moment when Zeus gives birth to the goddess of wisdom, warfare, and crafts: her mind, brain, and head.

The first section of the exhibition concludes with four photographs from Christoph Keller’s Archaeology Plant series (2014) — Hephaestion, Epidaurus Theater, Olympeion, and Poseidon of Artemisioion. These images feature plants superimposed on iconic scenes from ancient Greece. Continuing his exploration of the history of science and how the organization, compilation, and systematization of knowledge shape our thinking, Keller examines Western anthropology, focusing particularly on Western Europe’s connection to the Amazon region. In a way, he quite literally connects the dots.

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Arterritory.com

Next to it, on a small table, are two photo albums — one from the first Acropolis Museum, dated 1880, and the other dedicated to a pilgrimage from Athens to the Balkans and Constantinople in the 18th and 19th centuries. Viewers are invited to leaf through them carefully, wearing white gloves and observing the request not to open the pages of the old books fully, thus helping to preserve these ancient testimonies.

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Alexandra Masmanidi

The exhibition continues with “The Journey of Being” — a tribute to travel, both inward and across time, as an eternal quest for knowledge. It is a journey that unfolds throughout life, shaped by the people we encounter, the often inexplicable connections linking seemingly unrelated elements, and the presence of mystical experiences that defy rational explanation.

Among other works, this section includes a 1930 edition of The Odyssey, its monumental leather spine standing out against the view of modern Athens visible through the window. Also on display are five leather-bound issues of Ladies’ Journal, published between 1897 and 1907. The journal’s founder, Callirhoe Parren, was a pioneer of the feminist movement in Greece, and the publication was entirely run by women.

From left to right:

Panos Tsagaris (b. 1979). The Union, 2011, Gold leaf on newspaper, triptych, 56 x 30 cm each

Francis Alÿs (b. 1959). Camgun #67, 2008, Wood, metal, plastic, film reel, film, 48 x 62.5 x 42 cm

&

Francis Alÿs (b. 1959). Camgun #76, 2008, Wood, metal, plastic, film reel, film, 36 x 74 x 36 cm

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection. Photo: Nikos Alexopoulos

Opposite stands a painting by Pegeen Guggenheim titled Honeymoon, which obviously holds a special place within this unique tapestry of artistic experiences and discoveries. Pegeen was the daughter of renowned collector and philanthropist Peggy Guggenheim, from her first marriage to Laurence Vail. Raised within the vibrant art world, Pegeen nonetheless remained largely misunderstood. Although Peggy promoted her daughter’s artistic work, their relationship lacked emotional closeness. Pegeen longed for attention and a semblance of a normal childhood, which she never truly experienced — resulting in early-onset depression. Though her sometimes naive and slightly surrealist paintings are full of vivid colors and appear cheerful at first glance, they are imbued with deep melancholy and sadness. Peggy attempted to compensate for the emotional gaps in her daughter’s life through professional support, but ultimately to no avail. In 1967, Pegeen was found dead in her apartment from a drug overdose. Peggy never came to terms with her daughter’s suicide.

The existential search — and the inescapable link between life and death — is also central to the work of Greek artist Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika. His piece The First Morning of the World (Stage Set of Persephone), 1960, pays tribute to the Persephone. It depicts the moment she descends into the underworld — a symbolic confrontation with death, a universal and inevitable passage.

The third section of the exhibition symbolically moves outward from inner exploration. Explorations and Expeditions is dedicated to the relentless human curiosity to discover and conquer the unknown—one of the driving forces behind the development of civilization, continuously pushing the boundaries of knowledge.

This spirit of exploration reached its height during the Age of Discovery, when the desire to uncover distant, unfamiliar lands became a dominant force behind European expansionism. Driven by the need to establish new trade routes and exploit economic opportunities, European explorers embarked on ambitious voyages that reshaped the global geopolitical landscape. These expeditions facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures between the Old and New Worlds. However, they also came at a tremendous human cost, often resulting in the exploitation and subjugation of local populations.

From left to right:

Costantin Xenakis (1931-2020). Communauté européenne, 1982, Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 100 cm

Chryssa Romanos (1931-2004). Map – Labyrinth, 1997, Decollage on Plexiglas, 100 x 70 x 6 cm

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection. Photo: Nikos Alexopoulos

Cartography played a crucial role during this period. Initially rooted in oral tradition, it evolved through the shared knowledge of fishermen and sea captains who discussed routes and attempted to chart the world. As a result, early maps were often inaccurate and filled with speculative features. Among the historical examples on display is a map reflecting Magellan’s era and the widespread belief in Terra Incognita—a supposed landmass thought to exist south of South America. As we know, Magellan’s fleet passed through the Strait of Magellan at the continent’s southern tip, entering the vast Pacific Ocean. The lands south of the strait remained largely unmapped and mysterious, reinforcing the idea of a massive southern continent. Maps depicting Terra Incognita were frequently embellished with illustrations of mountains, fantastical creatures, and indigenous peoples—details often based more on imagination than observation.

Another special item is an engraving by British artist, medical reformer, writer, and traveler Selina Bracebridge, titled Athens, 1836. It is particularly noteworthy because, according to historical records, very few female “Grand Tourists” visited Athens in the mid-19th century. Bracebridge’s presence in Greece was exceptional, and she created this panoramic view of Athens, which – according to historical records, she later sold to raise funds for the Protestant Chapel in Athens.

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Arterritory.com

There are many works by women in Irene Y. Panagopoulos’ collection, and what connects them all is a shared mindset. These are women who explore themes that have always been important to Panagopoulos herself: women’s rights, human relationships, equality, and broader social issues.

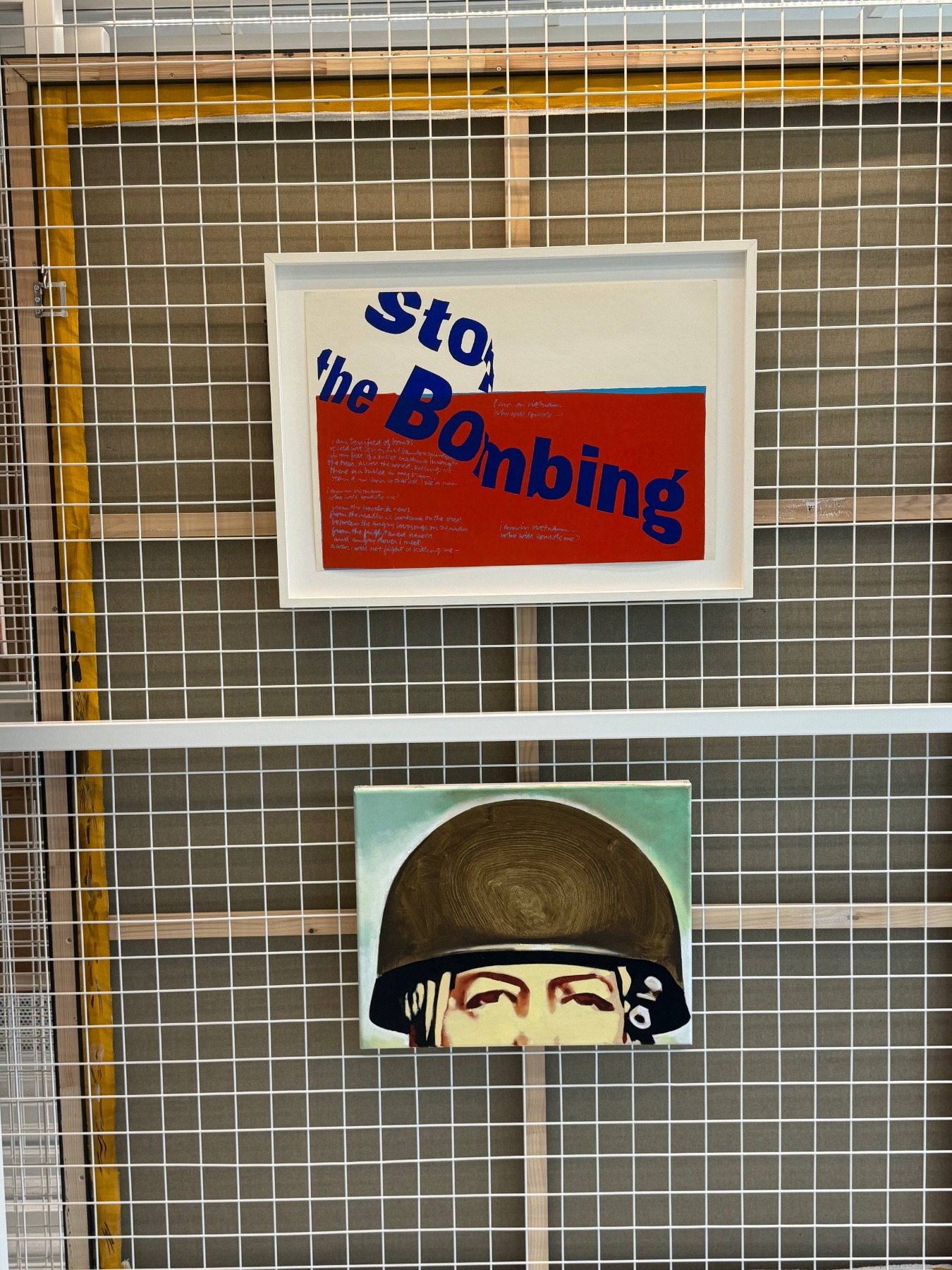

As part of the fourth chapter — Conflicts and Displacements — the exhibition includes a deeply personal work by Armenian-born artist Silvina Der-Meguerditchian, Vienna Carpet (2021). She grew up in Argentina, where her grandparents fled to escape the Armenian genocide—the massacres carried out by the Ottoman Turks against the Armenian minority in 1914–15. In her work, the artist reflects on her family history and the trauma endured by her grandparents, telling their story through functional objects they brought with them—preserving their history, culture, and personal identity.

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Arterritory.com

Symbolically, the final section of this journey-like exhibition is titled “Ideal Worlds”. Quoting the exhibition catalogue: “The elusive thread of the desire for the ideal often extends beyond the confines of present reality, weaving utopian or dystopian conditions where imaginary perfect worlds reside. On a collective level, the relentless pursuit of the ideal –frequently linked to the quest for social, economic, political, and environmental justice– gives rise to socio-political movements that resist oppressive structures of control, surveillance, and manipulation. However, the challenge to established authorities and the confrontation between opposing ideological systems often lead to conflicts that shatter initial expectations, revealing the inherent complexity of human nature.

Consequently, the critical stance toward reality or the longing for the unattainable frequently manifest as an escape into the realm of imagination. This escape may take the form of an idealized nostalgia for the past –whether referring to a glorified historical era, or one’s lost youth– or find expression in the creation of fictional worlds. Within these worlds, mythical creatures and transcendent realities serve as symbolic or satirical reflections of contemporary society, illuminating both its contradictions and its aspirations.”

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Arterritory.com

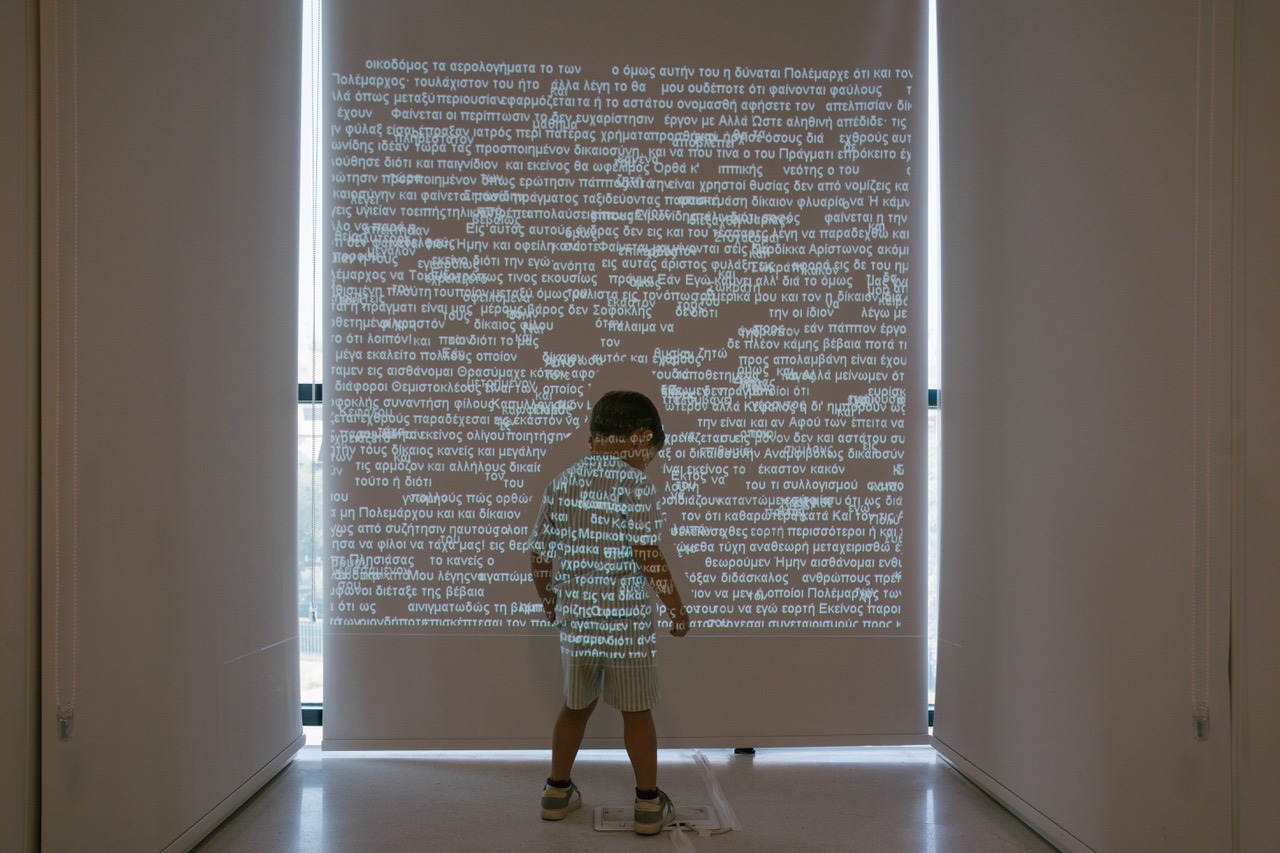

The exhibition concludes with Charles Sandison’s work The Republic (2013), a single-channel data projection—an algorithmic code that continuously synthesizes Plato’s legendary text. Through technology, Sandison immerses the viewer in the labyrinthine complexity of language, evoking a utopian ideal—one we may dream of but can never fully attain. And so the search continues: through exploration, encounters, discoveries, conflicts, chaos, and an unrelenting quest for harmony amid constant instability.

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection Space. Photo: Alexandra Masmanidi

Irene Panagopoulos’ collection space is accessible by appointment only and through guided tours. In many ways, it resembles reading a book that invites endless interpretation—an individual journey where dominant historical narratives intertwine with personal stories. It also represents a thoughtful, elegant, and sustainable approach to presenting a collection. In a world saturated with glamorous private museums, sometimes all it takes to make a powerful and meaningful statement is to simply open a repository – a library of human condition.

***

Curated by: Katerina Hadji

Featuring: Alexis Akrithakis, Francis Alÿs, Andreas Angelidakis, Yüksel Arslan, Richard Artschwager, Kader Attia, Minas Avramidis, Maja Bajević, Petrus Bertius, Selina Bracebridge, Vlassis Caniaris, Louis-François Cassas, Étienne Chambaud, Salvador Dalí, Paul Alfred de Curzon, Alphonse de Neuville, Silvina Der-Meguerditchian, Stelios Faitakis, Ormond Gigli, Pegeen Vail Guggenheim, José Gutiérrez de la Vega, Nikolaos Gyzis, Ernst Haas, Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, Thomas Hartley Cromek, William Heather, Lito Kattou, Christoph Keller, Bouchra Khalili, Rallis Kopsidis, Maria Loizidou, Kostas Malamos, Alain Manesson Mallet, Takis Marthas, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Ron Nagle, Adrian Paci, Giorgos Paralis, Callirhoe Parren, Angelo Plessas, Georgios Prokopiou, Polykleitos Rengos, Chryssa Romanos, David Sampethai, Charles Sandison, Wilhelm Sasnal, François-Louis Schmied, Sister Corita, Edward Steichen, Thomas Struth, Rosemarie Trockel, Panos Tsagaris, Yiannis Tsarouchis, Spyros Vassiliou, Eleni Vernadaki, Alix Vernet, Vincentius Demetrius Volicius, Johann Jakob Wolfensberger, Francesca Woodman, Constantin Xenakis, Raed Yassin and anonymous artists.

***

Exhibition Duration: 12 June 2025 - 27 February 2026

Opening Hours: Wednesday - Friday, 11:00 - 17:00

Address: 157, Konstantinou Karamanli Avenue, Voula 166 73 (entrance via 146, Vasileos Pavlou Avenue)

Admission only with reservation at: www.iypcollection.com

Title image: From left to right:

Rallis Kopsidis (1929-2010). Robinson Crusoe on His Island, 1958. Tempera on carton paper, 18.2 x 12.7 cm

David Sampethai (b. 1989). Don Quixote Staring at Imaginary Enemies / The Knight’s Return, 2017, Ink on paper, 46 x 31 cm

Sidsel Meineche Hansen (b. 1981). Gallery Pinocchio, 2020, Crayon on wood, 56 x 33 cm

Ron Nagle (b. 1939). Paper Βysmal, 2012, Ceramic, catalyzed polyurethane, epoxy resin, 18.5 x 16 x 7.5 cm

Alix Vernet (b. 1991). Inspection Νotice, 2019, Textile, plastic supports, 130 x 80 x 80 cm

Irene Y. Panagopoulos Collection. Photo: Nikos Alexopoulos