Constructivist’s Kitchen

04/07/2013

Gustav Klutsis. The Right to Experiment

State Tretyakov Gallery

7 June – 22 September, 2013

Gustav Klutsis was killed in 1938. It is not clear whether he was shot at NKVD’s Butovsky firing range or he was tortured to death during interrogation. Up until the end of the 1980s were convinced that he died in 1944, from a heart attack, at a camp. In his file, there is a list of works where his entire career from 1918 to 1938 is described as follows: “political posters – 75 sq. m, drawings in the newspaper “Pravda” – 4.9 sq. m, books, postcards – 5 sq. m, city decorations, panels, work in theater – 4.6 sq. m, analytical period: Cubism, Futurism, abstraction, photo collages – 3.2 sq. m. Total area – 100 sq. m”.

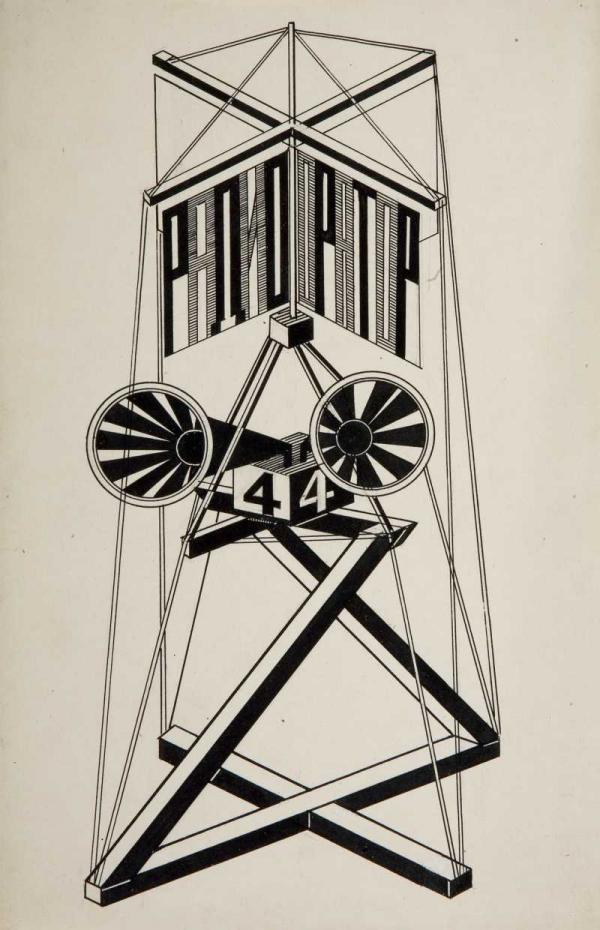

Design of installations for the 5th Anniversary of the October Revolution. 1922

At the exhibition in Moscow only a few square meters of this wealth is being shown. For the first monograph exhibit after a long hiatus, the Tretyakov Gallery has chosen the early period of the artist’s career: the late teens and early 1920s. On display, are three paintings, lithographs, sketches, projects, drafts. Klutsis at his most powerful, the famous Klutsis – author of propaganda posters, postcards and print graphics – is not present in the two small rooms hidden in the depths of the exhibition of Russian art of the 20th century.

And even in these two halls, the works of Klutsis seem not to command center place. At first one’s eye is caught by a huge metallic construction with the artist’s name, which takes center stage of the exhibition, while the small pieces of paper, filled with much more sophisticated constructs, have been scattered over the walls without much thought to their neighbors. The second hall is swathed in semi-darkness: there are rows of chairs and a large screen where the documentary by Pēteris Krilovs “Klutsis. The Incorrect Latvian” is being shown, whereas important, albeit few items from the Latvian National Art Museum, Liechtenstein’s foundation SEPHEROT and archive RGALI, all looking orphaned, have been hung around it. It is not dark enough for a quality screening of the documentary and too dark for the graphics to be viewed conveniently. The great big film by Krilovs, made using Klutsis’s collage aesthetics, seems to quarrel with the exhibition and does not help to concentrate on the works.

It must be difficult for the unprepared viewer to realize that the exhibition is a presentation of one of the most striking constructivists, a globally famous star of graphic design, an artist who in many ways set the language of propaganda of the victorious socialist revolution and at the same time a man of a tragic destiny who was sincerely devoted to the regime, which disposed of him in such a cruel way. Gustav Klutsis, a subject of the Russian Empire, was born in a working class family in a small Latvian village. He managed to attend good art schools in Valmiera and Riga and when, before the First World War, the factory where his father worked was evacuated inland from the border, found himself, along with his family, in St Petersburg. In 1915, he was drafted and, parallel to his army duties, he attended the School of the Imperial Society for Popularizing the Arts. He greeted the revolution with enthusiasm and did not return to Latvia; his dreams of a just social order were reinforced by his personal hatred of the tsarist regime: as the uprising of 1905 was suppressed, his older brother was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor. In 1917, Klutsis entered the 9th regiment of Latvian riflemen, taking part in the October coup d’état. According to legend, he was among those who guarded Lenin and the Soviet government, which moved from Petrograd to Moscow. In 1919, he joined the communist party. Among the Latvian riflemen, there were many artists, and after an exhibition at the Kremlin, some of them received instructions to continue their education. Klutsis was lucky: he ended up at the Free Workshops, which soon enough were transformed into VHUTEMAS, an innovative educational establishment.

Radio Orator № 4. 1922

That is where the transformation of an academic painter into an avant-garde artist began. Klutsis found himself at the heart of revolutionary artistic life. He strove to “exhaust, in strenuous work, all trends and ‘isms’ and thereby free himself of the burden of the past, of the old school, an to find new forms for the present”. “The Red Man” of 1918 from the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery is a good example of Klutsis’s familiarity with European modernist painting. A sketch for a panel for the Bolshoi Theater, “Storm”, also of that year, from the Riga museum, is the first example of collage, the technique for which he is mostly remembered. In 1919, he studied at Malevich’s studio and participated in the exhibitions of Malevich’s UNOVIS. The lessons of suprematism have been wonderfully mastered in a suprematist collage from the private collection of Guntis Belēvičs from Riga as well as in the lithograph “Dynamic City” and in the “Axonometric Painting” of 1920 from Tretyakov. This classic canvas, accompanied by a sketch, should not be hidden in a corner. There, important paths of Klutsis’s development are already evident; albeit construction still evaporates in a white suprematist void, it already possesses three points of axonometric construction and a vividly expressed materiality. For added effect, the artist adds metal shavings, sand and glass to the paint. This is almost counter-relief and an exit from suprematism into constructivism. Together with El Lissitsky, Rodchenko, brothers Stenberg and others Klutsis insisted on the right to experiment – these are the words, borrowed from his manuscript, that have been chosen for the title of this exhibition.

Photo: Press Service of the State Tretyakov Gallery

Having finished his studies, Klutsis taught at his alma mater, VHUTEMAS, which was later renamed VHUTEIN. Until 1930, when the institute was dissolved in the course of the “battle with formalism”, Klutsis carried out a program developed for the “revolution workshop” and published in the first issue of the magazine LEF (Left Front of the Arts). Students were raised into “socially mature artists”, “artists-practitioners who have set themselves the aim of impacting the mass viewer”, armed “to their teeth with all the contemporary achievements of science and technology “. Behind this revolutionary rhetoric, there was the experience of avant-garde art and lessons of another famous school, the German Bauhaus. Chromatic and spectral tables presented at the exhibition come from the famous collection of G. D. Kostaki who was forced to share it with the Tretyakov Gallery in order to be allowed to take the rest with him to Greece in 1977. These tables vividly call to mind not only similar works by A. Rodchenko but also the materials of the Bauhaus masters, Johannes Itten and Paul Klee.

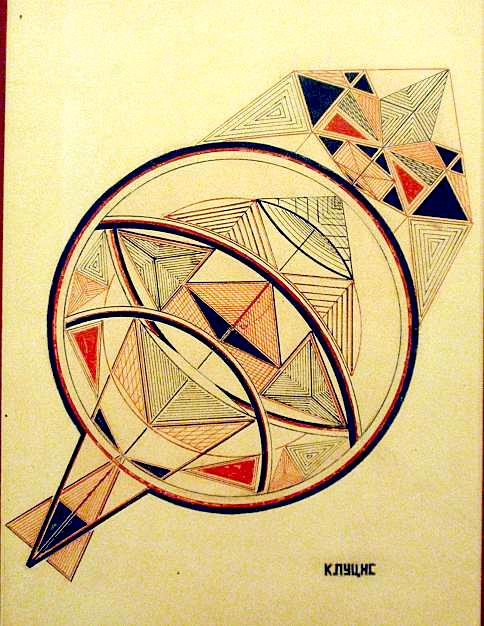

Construction (Fantasy). 1920

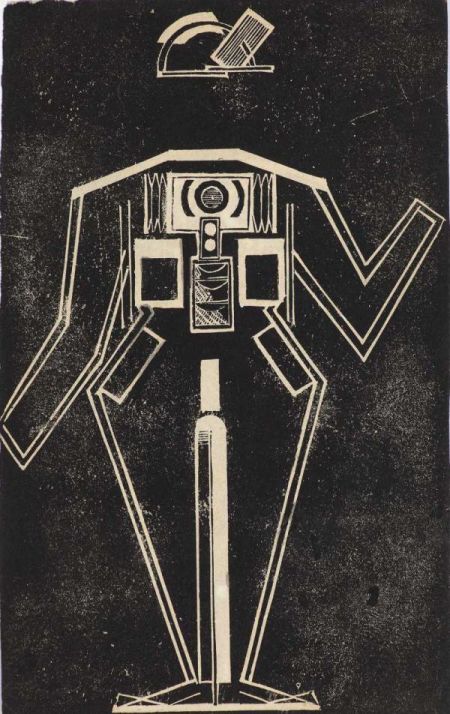

Klutsis’s personal art at that time develops from non-objective compositions of complex, dynamic geometrical forms, as in “Construction (Fantasy)” from the Belēvičs collection, “Spatial Organization” from Tretyakov and the many “Constructions” given as gifts to Kostaki to graphic projects of spatial-environmental objects. And here Klutsis is a genuine pioneer of constructivist design. In 1922, for the fifth anniversary of the revolution and the fourth congress of the Comintern, he designed propaganda installations for the streets and squares: radio rostrums, booths-screens, spatial slogans. In the sketches for these fantastic yet at the same time rationally thought out installations that could undergo different transformations if necessary, Klutsis comes across as a worthy member of the group of artists of the Institute of Artistic Culture represented by Rodchenko. Stepanova, Popuva, Vesniny et al. His engraved sketches of workers’ and sports clothing stand side by side with the workers’ clothing by Tatlin, Rodchenko and others.

A set of worker’s clothing. 1922

The famous collage graphics were born out of his non-objective compositions. He managed to successfully combine the page organized according to the rules of suprematism and constructivism with almost Dadaist-like use of photographic image. The present exhibition, however, merely hints at this period. A tiny photo-collage for the famous poster “Let us carry out the plan for great works” where the artist immortalized his own hand in a surrealist manner, an illustration “For Struggle” based on a story by Y. Libedinsky, another couple of sketches – and all the rest can be viewed only on screen, in Krilovs’s documentary.

The monumental art by Klutsis also remains outside the limits of the exhibition. A universal master, like many of his contemporaries, he designed for workers’ clubs and installed Russian and international exhibitions. An exhibition in Paris meant his only trip abroad. In 1937, he went to France to work on a panel «8th Extraordinary All-Union Congress of Soviets and Constitution of the USSR” for the Soviet pavilion. In Paris, he painted beautiful cityscapes – rumor has it that there are close to 150 in Riga. Upon his return, he continued to prepare for an anniversary exhibition and international exhibition in New York but fell victim to the mass campaign of liquidating “nationals” being arrested as a member of a counter-revolutionary fascist terrorist organization under the auspices of the Latvian association “Prometheus”. His rehabilitation came only in 1956.

Photo: Press Service of the State Tretyakov Gallery

The fate of Gustav Klutsis, against the background of the events in today’s Russia seems especially poignant. It is possible to be devoted to a regime, to be in demand by it, to brilliantly perform your professional tasks, to faithfully follow the bends in the party path – there are sketches for photo posters of Klutsis from which the images of repressed people disappeared after the fact – and still end up in the same slaughter house. It is a pity that the Tretyakov Gallery decided to take such a chamber-style, academic, know-it-all approach for the first encounter for the wider public with this great master. It is strange to start an official acquaintance from the kitchen.