Q&A with the curators of the TAB Urban Installation Programme, Sille Pihlak and Siim Tuksam

12/09/2017

At the center of the 3rd international Tallinn Architecture Biennale (TAB) in 2015 was the theme of “Self-Driven City”, an idea that looked at the effects of the potential third industrial revolution, i.e., how the evolution of the newest technologies will change architectural processes, urban planning, and daily social processes.

This year the 4th Tallinn Architectural Biennale, taking place September 13 to October 27, is titled bioTallinn, and it explores cityscapes as self-organizing systems. Claudia Pasquero, the main curator of the 4th TAB, takes a non-human-centered position towards urban space, focusing on biotechnology in architecture and urban planning.

The program of the Biennale consists of three main events and satellite programs under the theme of bioTallinn: The core includes the Curatorial Exhibition, the Symposium, and the Tallinn Vision Competition. The key TAB 2017 satellite programs include the Installation Programme competition exhibition and the TAB Schools Exhibition, bio.School.

.jpg)

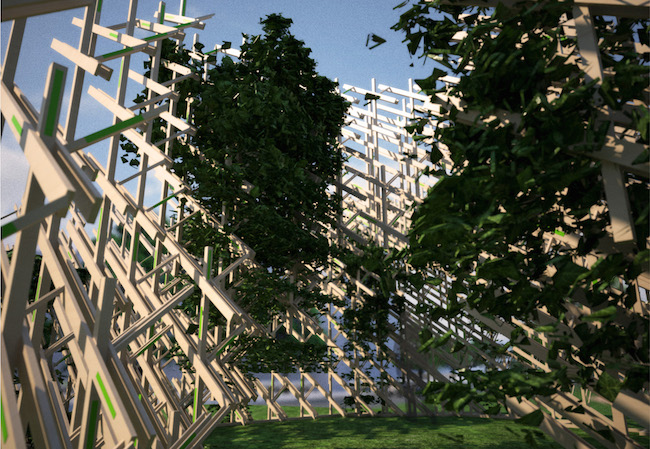

Gilles Retsin Architecture, TAB2017

The TAB 2017 Installation Programme offers emerging architectural talent the opportunity to design and build an exploratory installation in the city center of Tallinn, on the space in front of the Museum of Estonian Architecture. The winning proposal by Belgian architect Gilles Retsin is characterized by outstanding aesthetics and a novel use of plywood. The concept of prefabrication of timber elements is gaining more and more traction in the timber industry, and new products combine low-grade materials such as OSB with higher grade timbers. Timber panels are a good reference for what is possible with CNC milling and relatively cheap timber products. Gilles’ design for the TAB 2017 pavilion is based on a few simple elements – stiff, hollow timber boxes – which are easy to prefabricate and can be quickly assembled into a structure, just like LEGO.

Sille Pihlak and Siim Tuksam. Photo: Mark Raidpere

The curators of the TAB 2017 Installation Programme are the architects Sille Pihlak and Siim Tuksam (part.archi). This year the duo was awarded the Estonian Young Architect Award. In selecting them as the laureates, the jury highlighted their close cooperation with the Estonian wood industry, their widespread advocacy of wood as a building material, and their activities in the field of architectural education.

The installation in the area in front of the Museum of Estonian Architecture, made by Gilles Retsin, is taking the form of a wooden folly. Why exactly this architectural form and not something more functional? What is it about follies that inspires you?

Siim: I think function is way overrated in architecture...in capital-“A” architecture, that is. Function, as we think about it, mainly means its program, or how humans will inhabit the said architecture. But there are way more functions to it – there is the way in which it reacts to its environment, so a folly needs to function in terms of structure, in terms of environment; the only thing that is excluded is it having to have the function in which people go inside of it and do something specific in its interior space. This helps us to look at perhaps more experimental ideas about where architecture might be going – instead of solving issues of access and enclosure, and stuff like that.

How is Retsin’s work specifically linked to the Biennale’s overall theme of “bioTallinn”?

Sille: Retsin is a kind of interesting character in the field of architecture, as well as in this specific discourse, because he is quite strong in theory and practice. He is really cultural-discourse driven and tries to find answers to certain questions. He was distinguishable from all of the other architects because he was constantly anti-biomimicry, anti-making-things-look-biological, and against copying ideas from nature. We are not nature, so why we are trying to mimic something that is not there? He looks more modernist in his approach to man-made architecture. His approach is strong and bold, and interesting in the way that it connects to this year’s Biennale. If we’re talking about “bio”, we should actually be talking about man-made nature and not about nature-made nature.

Also, there won’t be much bio-mimicry in the main exhibition of the Biennale; this time it will be more focused on wastelands – how much untouched nature do we actually have left, and how much is man-made nature...

Siim: …or can we even make this distinction? Where I wanted to go with my previous comment about nature culture, is that follies used to be in those English parks in which they imitated a natural landscape and then imported an architectural piece of a Chinese temple, for example. We want to continue this discussion between man-made and nature. That is, if we can even make a distinction, because nowadays actually everything is affected by humans. And I think that this year’s main topic also asks people to take a second look at it – from the perspective of separating real nature from the man-made. Shouldn’t we start designing by keeping that in mind, and not by saying – this is preserved from nature and we’re keeping our hands off of it, and this is what humans have made. Perhaps we can bring these things together and create a symbiosis of nature and human.

Digital Building Blocks. Gilles Retsin, TAB2017

Could you please elaborate more on the aesthetics of Retsin’s project?

Sille: He has built something bold and strong, with big elements that are assembled from smaller and thinner surface materials – boards. Instead of using raw material, he used boards of it and assembled them into seemingly bigger volumes that look as if it should be a bulky thing. It appears as if this construction would require intense technological assistance, a crane and a lift, but it doesn’t. It was built right there, on site, from small units and with minimal technical support. Timber modernism is coming back. He believes that timber will be the 21st century’s building material. He even gives lectures on this subject – that timber is the future. It is interesting to have someone who is so theoretically driven and who has come here to use our local industry, who combines it with his knowledge in order to showcase the potential of it.

Siim: In terms of aesthetics, I just want to add that it is a very fresh approach to so-called discrete architecture – using repeating elements to create complexity, or building up from smaller components, like Legos, that you can assemble in certain ways and create anything out of. In a way, it is like a toy. And it is a very topical discussion at the architecture school – how you go from digital to physical, and how we can build physical things in a digital manner when you have pieces that fit together in a certain way and that can be aggregated into bigger things.

Sille Pihlak and Siim Tuksam’s installation at the Museum of Estonian Architecture, as part of Body Building, the main exhibition of the 3rd TAB. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

It stands somewhere between sculptural work and architecture. In any case, it seems that this structure will elicit public debate...

Sille: It is already there. Everybody is trying to figure out what this thing is in front of the building [in reference to Sille Pihlak and Siim Tuksam’s installation at the Museum of Estonian Architecture, which was part of Body Building, the main exhibition of the 3rd TAB]. They call it a spider, they call it a dinosaur… they need a name for it, but we never gave it a name. It is sort of like a cloud in which everyone sees what they see and they can name it as they wish. But it is more about showcasing the method, the idea about the kinds of things that you can do with fabrication tools and the fabrication machinery currently available. We showed how this object could be made from various elements.

It was at the starting point of the Biennale – it points in the three main directions and that’s why it has three legs: it is pointing at the Viru, where the Vision Competition took place; it is pointing at the second floor of the Museum of Architecture building, where the main exhibition was; and it is pointing to the Culture Cauldron.

Siim: I think what is really great about this year’s installation is that it is completely the opposite of what we were saying. It will show how standard elements can be configured. So, it is within the same paradigm of algorithmic architecture, but it is about a completely different idea.

The aim of the project is to promote synergy between designers and industry. What is practically going on at this level in Estonia?

Siile: We understood that the architectural sector focused on timber structures was very small. We usually cut down the trees and sell them abroad; we mill them a bit, but then we export them as a raw material. That timber has no architectural design value. And now, when we were creating this installation and making use of all of the industry connections we had, no one was really willing to come and say – “Yes, you can use our machine” – because these machines are very expensive. I think that the collaboration stage is not yet there, but I think that what we are trying to push with this installation, is that instead of timber being one of the biggest export goods for Estonia, we could get the timber industry involved in architecture or design ideas. Then we could create new and different economies – a design and culture part, and an industry part – and they would work together and both would gain from this previously export-only good. Perhaps we could start building in a more urban context and have more timber in the cityscape. We have a high potential to do that.

Siim: It is a very exciting time in this field because industries have the new technology, the machinery, and we have the tools that connect well to this machinery and which have been created to work together with it… What is still lacking is a willingness and a public demand for these kinds of projects. We are working on this now, through these projects. There have been collaborations between the wood industry and the Estonian Academy of Arts for eleven years – first-year students build shelter structures every summer, but until now, there hasn’t really been a discussion about building, for example, civic buildings out of wood in the cityscape. Actually, this subject has also come up at the government level over the last few years.

Sille: We are working together with the Ministry of Finance to push the idea that, in the next ten years, 50 percent of the buildings that will go up through public competitions have to be constructed out of wood.

Recently we discussed what the maximum age of a building should be – how long should it stay there. If we pour it out of concrete, it will be there practically forever, and its eventual tearing down will be an enormous amount of work. There are changes in terms of needs. We don’t need any more post offices or libraries, but we do need different kinds of places that are adjustable and flexible. Therefore, we should take advantage of timber’s characteristic of being easily readjustable or changeable, and the relative ease of taking it down to make something else from it. We should take advantage of its light weight and material durability.

Siim: And even if you burn it, to get energy out of it, more wood will grow back.

Sille: There is that funny statistic that all of the timber necessary to build one family house, 80 m2 in size, can grow back in an Estonian forest within one minute.

.jpg)

Returning to the Installation Programme, how many proposals did you receive for this competition?

Siim: The competition was organized in two stages – in the first stage we only asked for a portfolio, so that we could select the participants. We had 200 portfolios come in, and we chose 16 in the first round.

Sille: This competition was for young emerging architects. We saw how dramatically these sorts of competitions were being organized for, say, the Guggenheim Museum in Helsinki. The huge amount of work that was invested by the numerous numbers of applicants – that was absolutely unnecessary! That’s why we chose this method. Let’s see what the architect has done so far, and we’ll be able to tell if their work is suitable for this competition. And only these 16 were then asked to submit a project for the competition. We used architectural talent resources in a more efficient way, and the results were super-interesting. Knowing that they have to compete with 15 other architects, and not 116, they created their projects with much more care. The theoretical part, in which they had to give a statement in terms of bioTallinn and their thoughts on working with the timber industry, was also done much more thoroughly. We were happy with the results!

Second place in the competition was awarded to Tom Svilans and Paul Poinet (Denmark)

The third place in the competition was awarded to FLOW Architecture (UK)

Honorable mention of the competition: APPAREIL (Spain)

Honorable mention of the competition: LINKSCALE (UK)

Such a large number of applications also gives insight about the kinds of ideas that are in the air at the moment. What are your conclusions from this competition?

Sille: For me, it seem that some of them, one half, was trying to deal with some kind of bio-mimicry. Because when you hear the term “bio” – you visualize that. You see some kind of complex structure that is somehow driven by certain kinds of biological systems – in terms of materials and resulting volumes.

Siim: I think it is really hard to come to any conclusions about the current environment based on just those 15 because we also selected people who were different. The selection was already curated to bring a different kind of result.

I think there were some approaches that were really heavy on the competition side – the designs were generative and based on algorithms, and some were so complex that they could hardly be constructed with today’s means. Others looked more at fabrication technology. There was one project that looked at free-form glulam, which is something that is not really produced at the moment, but they are figuring out ways in which to double bent pieces of wood. It was a really appealing entry, but the industry just isn’t there yet. But it was a very strong contestant.

Museum of Estonian Architecture

Ahtri 2, Tallinn

2017.tab.ee