Ando Keskkula, technological determinist

A retrospective exhibition of the works of Ando Keskküla (1950–2008) in the great hall of the Kumu Art Museum

From 22 May through 13 September 2020, a retrospective of Ando Keskküla (1950‒2008) is on view in the Great Hall of the KUMU Art Museum in Tallinn, spanning the artist’s career from the late 1960s to the mid-2000s. The Reality and Technodelics exhibition is curated by art historian Andres Härm. The exhibition is also accompanied by a book that provides an in-depth overview of the artist’s body of work and biography.

Over several decades, Ando Keskküla dealt with the relations between art and reality, and with the impact of technology on culture, people and their senses. Keskküla’s happenings, drawings, paintings, animated films and interactive (video) installations are characterised by contrary sets of concepts, such as natural/technological, utopian/dystopian, and psychedelic/real. Until the 1980s, Keskküla dealt with the relationship between reality and its depiction and the impact of technology on the senses, primarily using the tools of painting and animation. In the 1990s, new interactive (video) technologies began to predominate in his work, which led to the involvement of viewers and the manipulation of their frames of mind in a totally different way. Unlike many of the members of his generation, Keskküla survived the upheavals that occurred in society and the art scene during the 1990s quite successfully. The issues related to subjectivity, society and technology became especially topical then, at the start of the digital revolution and internet age. But these topics had already appeared in Keskküla’s work in the 1960s and 1970s.

Ando Keskküla. Milieu with Packages. 1973. Oil on canvas. Merle Keskküla’s collection

“Keskküla understood that the social and technological processes that had been triggered would fundamentally change both global relations and people themselves. Nature and the artificial environment, the level of digitalisation in everyday life, altered human relations and communication, the trustworthiness of the media created images and the manipulation of reality are all themes that are more relevant today than ever before,” is how Härm describes the artist’s work in the contemporary context.

Ando Keskküla. Evening. 1975. Oil on canvas. Art Museum of Estonia

We got in touch with the curator of the project, Andres Härm, whom we know as the long-time head of the independently-founded institution that is EKKM (Contemporary Art Museum of Estonia), to ask him a few questions regarding the exhibition and the idea behind it.

How did you personally develop an interest in the work and ideas of Ando Keskküla? Was this show an initiative of yours or a proposal by the museum? Did you know Ando personally during his lifetime?

The initiative came from the museums side, it is part of their contemporary classics series and I was honored to be invited by Sirje Helme herself who is not only the director of Estonian Art Museum but also was the spouse of Ando for almost 20 years. I became the student of Estonian Academy of Art in 1995 when Keskküla became rector. At that time of course our paths barely crossed due to the “class difference” but in the early noughties we happened to travel on some occasions together like with the all-Baltic touring exhibition “Baltic Times”. In 2005 when I was the curator at the Kunstihoone in Tallinn he agreed to design my exhibition “No Painting” – I won even the Kultuurkapital award for that show and I think it has something to do also with his skills and eye as an exhibition designer. He was a well known exhibition designer not only in Estonia – in the mid and late eighties he designed several international and all-Soviet-Union exhibitions in Pushkin Museum and Manege in Moscow. There is also very interesting interview with the Moscow architect Yevgeny Asse, his main collaborator at these projects, in the book accompanying the show. They were invited to be part of a team to design the project USSR- USA: The 20th Century, a huge exhibition to take place at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington and in several places in Moscow, but the Soviet Union collapsed in the meanwhile.

But Keskküla was, of course, an artist very hard to avoid when you got interested in art in Estonia. I think I probably first got to know his works from the catalogue “Estonian Painting” published perhaps in 1984 and was as an adolescent, of course, blown away by his works from the hyperrealist period that is perhaps his most celebrated one. When I entered the Art Academy by the mid nineties Ando and his generation were already classics but he was also one of the leading figures in the 1990s new media and interactive art and although I perhaps value even more his activities as a curator of exhibitions and initiator of events like Interstanding at that time, he made at least two unavoidable classic pieces also in that period. I remember I was astonished by his Crazy Office installation from 1997 at the Interstanding II exhibition that he also curated as well as by his Breath from 1999 that was first exhibited at the Estonian Pavilion in Venice Biennale. So in a way I have been always keen on his work.

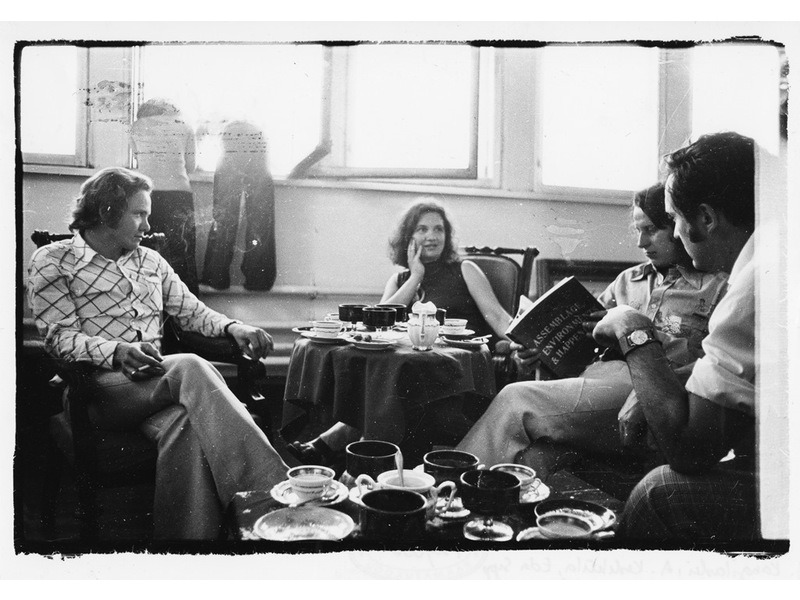

Ando Keskküla, Eda Sepp, Andres Tolts and Jaak Kangilaski. 1975. Photo: Eesti Kunstimuuseum SA

What is your take on the role of Ando Keskküla in the Estonian art of the 1970s-1980s? How was he viewed both by ‘mouthpieces of officialdom’ and by the underground? Did he pursue his subject as a loner or was he part of a movement?

Well, we can speak even from the sixties. He was the central figure in Estonian pop art movement and the SOUP ’69 group with Leonhard Lapin, Andres Tolts, Ülevi Eljand, Vilen Künnapu et al. Ando mostly working together with Andres Tolts made assamblages and collages, built environments and made some installations. They also organized POP-evenings at his parents house in Nõmme district in Tallinn on Raja street 6a (he has also two paintings from the late seventies depicting that address) were concerts and poetry readings took place and where the underground youth met. With the SOUP group they organized happenings that got them in trouble and they came close to be expelled from the Estonian State Art Institute (ERKI). One happening Papers in the Air in 1969 at the Pirita beach got them arrested and thrown to the Patarei prison. They received ten days imprisonment for hooliganism and were saved from expelling from the ERKI only due to the intervention of Künnapu’s aunt Olga Lauristin who was a legendary communist revolutionary. Their heads were shaved but Ando managed somehow to keep his hair and used it later in the assemblage Head in a Bowl that was exhibited in the Progressive art of Estonia show in 1970 at Pegasus café, trendy meeting place of cultural avant-garde at the time. In the seventies Ando became the leading force of the Estonian version of hyperrealism. Hyperrealism got sort of accepted and was celebrated all over the Soviet Union because it was modern and realist at the same time – thus adobtable into the official realism doctrine still dominating in the Soviet Union, although its aesthetics were cold, alienated, urban and technodelic. In 1976 Keskküla became the member of the Artist Union and the Head Artist of Art Foundation. In Estonia the limits between the official/ unofficial art scenes were also not that strict as for example in Moscow, so he could easily operate in-between them. Due to his position at the Art Foundation he could organize that the Foundation bought the works of the young and more radical artists and due to that this collection was much stronger than the Art Museums entering the nineties. In 1985 he became the associate professor at the painting Department and from 1989-1992 he was the President of the Artist Union, so he held solid institutional positions already in the Soviet time.

Ando Keskküla. Industrial Interior. 1977. Oil on canvas. Art Museum of Estonia

Could you tell a bit more about the ‘interactive (video)technologies that allow captivating the viewer and manipulate with his feelings in a completely different way’ that caught the interest of Ando Keskküla in the 1990s? How are they represented at the exhibition?

Unfortunately most of his interactive video works are now lost -- computers crashed etc. They could be restored if the source videos would be found since the technicians he worked with could easily restore the technological solutions behind them. Despite our efforts we could not find the source videos. Only one them, Breath is preserved because it was bought by the Tartu Art Museum and was fully restored few years ago. The other interactive work on this show is the second version of Crazy Office installation that he made in 2004 at the Retretti Art Centre in Finland. It was restored for this show by Keskkülas main collaborators Kalle Tiisma and Toomas Vinter based on photos and their recollections.

Ando Keskküla. Evening News. 1982. Oil on canvas. Tartu Art Museum

Why does the title of the exhibition feature the term ‘technodelics’? To what extent can technologies be psychedelic (if that is the context it refers to)?

Technodelics is a term that Keskküla himself did not use. It was formulated by the next generation artists Raoul Kurvitz and Urmas Muru for their Manifesto of Technodelic Expressionism in 1988. However, I understood that this term combining technology and psychedelics (altering one’s senses) is something that could be used to characterize also Ando’s works. He was convinced that technologies as the extensions of man alter not only society but also the subjects. They alter not only their senses but they produce new kind of subjectivity. Being a industrial designer by education this somewhat mcluhanian conviction (whom he quoted directly) was already expressed in his diploma thesis 1973. As Mari Laanemets points out in her essay for the book, for example, all items depicted in Keskkülas painting Northern-Estonian Landscape from 1974 – the light bulb, book, tube of paint, razor and envelope are not random objects, but consciously chosen “means of communication” that have changed people’s relationship with reality. This makes his turn towards new technologies in the nineties – dawn of internet era, new means of interaction etc – utmost understandable. I presume that for him the changes in the information technologies in the nineties were much more radical and revolutionary than the change of the political regime at turn of the decade. This truly altered peoples lives, their reality, their way of life and understanding of the world. So he was, in a way, a kind of technological determinist. But the technodelics term also coins a possibility of the bad trip i.e. he was not always optimistic about these shifts and changes. There is also this strong dystopian motive in his ouvre that one could also trace back to his diploma thesis. He made for his thesis a script draft and sketches for the animated film Bluff, where the main character is a kind of tv-salesman that offers stuff – all kind of objects, produced goods etc – to viewers through the screen but suddenly the things start to get stuck to him and he ends up being fully covered with them – only one blinking eye visible underneath. So it is a kind of prediction of the Japanese cult film Tetsuo from the eighties. But this motive of things “getting out of hands”, becoming animated and taking control against the peoples will, can be seen in several of his works like the animated film The Hare, where accidentally produced mechanical hare comes to life or his Crazy Office installation in which, a typical, indifferently furnished business office goes crazy. The chairs jump around and throw themselves onto the floor, fall over and stand up, and a jacket sleeve on the back of a chair moves up and down. It is an ironic metaphor for the new business culture that started to proliferate in post-socialist Estonia during the 1990s. In its destructive manner it erects a kind of “anti-monument” to the hyper-neurotic cult of success typical of the new yuppie culture and a work ethic that ends with burnout. Crazy Office II is even more brutal and very laconic: all spatial simulation has been abandoned and only a purely destructive form is preserved, the crazed, aggressive and rowdy chairs. In its minimalism, this is technodelic dystopia in one powerful image, and summarises Keskküla’s aspirations as an artist quite well.