Art is always ahead

An express interview with Lithuanian curator Valentinas Klimaušauskas

At the Centre for Contemporary Art FUTURA in Prague, the exhibition The Cave & The Garden, a group show that contains mostly works created during the last two decades by artists from Central and Eastern Europe, is currently ongoing through September 27. The works reveal the multifaceted and problematic nature of our societies and the world, focusing on issues such as the current conditions of quarantine and COVID-19 wave(s), the activation of nationalist inclination and border-building, social unrest, rising commotion in response to the racist and colonialist past and present, the sixth extinction, and others.

Valentinas Klimašauskas, curator of The Cave & The Garden, answered the following questions posed by Arterritory.com

The theory behind The Cave & The Garden is based on the concepts of Plato’s ‘Cave’ and Voltaire's ‘Garden’. How did the idea for such an exhibition come about? What was the trigger that led you to these chrestomathies?

The title could also refer to, for example, Adorno, but I specifically wanted to move even further back in the past. In 1969, a Spiegel journalist started formulating a question: ‘Professor Adorno, two weeks ago, the world still seemed in order…’ but was interrupted by the professor saying: ‘Not to me.

No one needs to be reminded of the mantra that we live in a historical time of changes, turmoil and unrest, and that an older, historical non-positivist perspective might be useful to understand our situation and to question its supposed exceptionalism. I’m in quarantine now and watching online protests in Belarus (as we all are/were following and/or participating in the Black Lives Matter, Yellow Vests, and LGBT social movements, the forthcoming presidential elections in the USA, etc.) thus, I’d like to start by saying that I find the collage or hybrid of two classical allegories of the world as a cave and a garden to be very contemporary and relevant.

Jaakko Pallasvuo. “the way you almost wholly omit to flower”. 2020. Pages from the PDF book. Various locations throughout the exhibition

I will briefly explain the allegories. The idea of the world as a cave explains reality as an ideological theatre of shadows – the post-truth world that we find ourselves in – and it directly connects to us being locked into our apartments (i.e. caves) during quarantine, trying to understand which actions and sources of information are truer than others.

The allegory of the need to ‘cultivate one’s garden’ comes from Candide, as written by Voltaire in 1759. At that time the world also did not seem to be in order – the satire refers to historical happenings such as the Seven Years’ War and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, and it also ridicules colonialism, positivism, theology, governments...you name it. His idea of the world – i.e. one’s life, artistic practice or someone’s mind as a garden that needs to be cultivated to bring meaning – also connects to the new trend of gardening during the lockdown, but also to ecological thought (for example, Donna Haraway’s sympoesis, and critique of the divide between nature and culture as expounded by the likes of Theodor W. Adorno, Bruno Latour and many others) or the importance of cultivating one’s artistic practice. In the framework of the exhibition, the phrase ‘cultivation of one’s garden’ may be interpreted as cultivating one’s life, profession or the global eco-socio-political system. However, this idea reveals a paradox – when cultivating a garden, one changes the nature of the world determining the garden that one is trying to cultivate, and so on and so on...which is also a very Adornian and very contemporary theme.

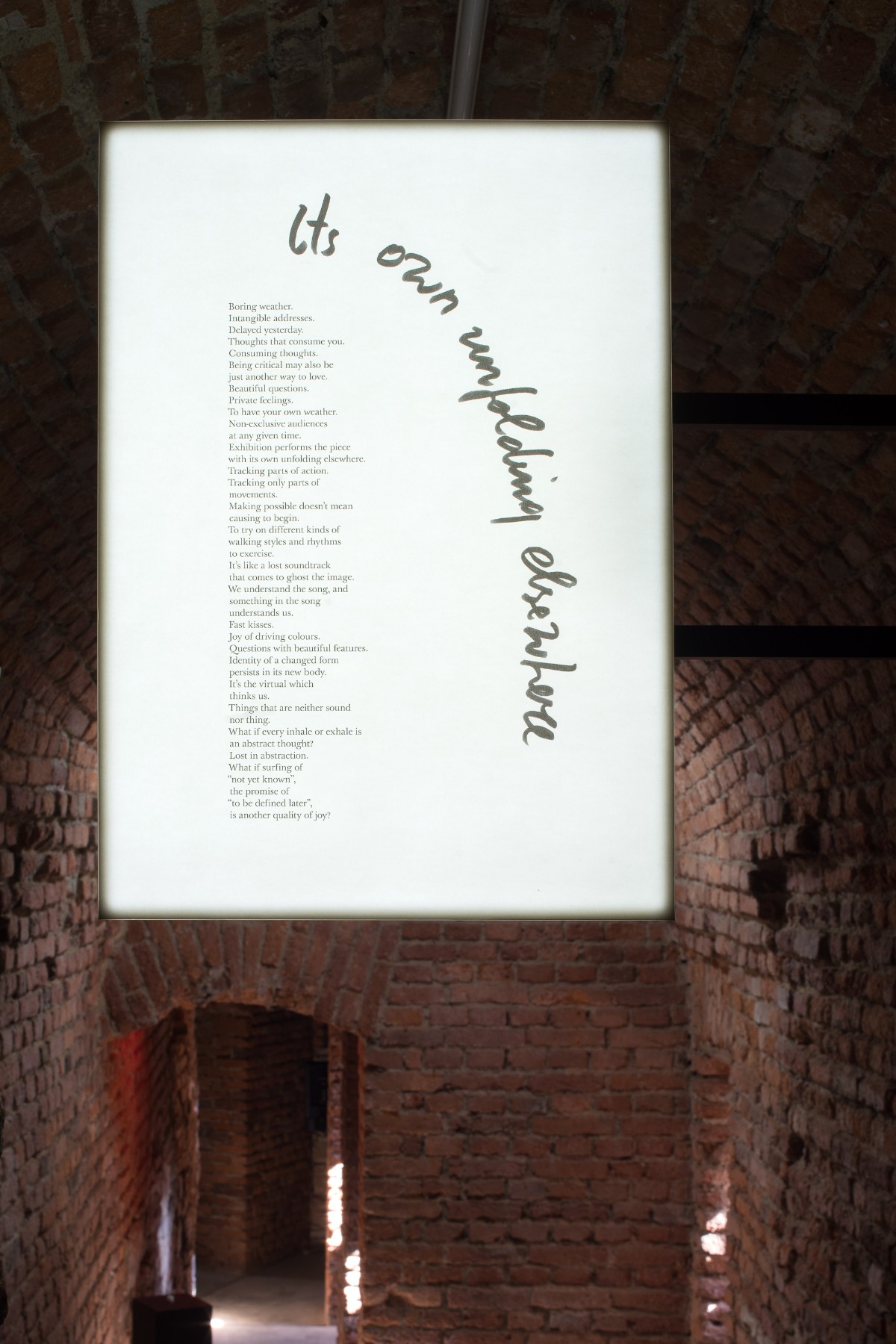

Laura Kaminskaitė. “Its Own Unfolding Elsewhere”. 2019. Text, light box (42 cm x 60 cm)

However, I’m more interested in the hybrid of the two allegories than the allegories themselves. For so-called cavemen, an act of seeing and understanding may be interpreted as a rather passive and solipsistic act, while gardening is seen as more active and, possibly, as a world-changing practise. However, to act, one has to have a clear understanding, hence, once again the gardener’s dilemma is also a caveman’s dilemma. In this context, both the artists and spectators may be seen as drifters between the two allegories: as cavemen who need to differentiate between projections and ideologies; and as gardeners who cultivate certain ideas and practices in various artistic formats, poetic gestures, research, or socio-political manifestations that may have an impact on so-called nature and vice versa.

Referring to the exhibition, the poetical drawings and writings by Laura Kaminskaitė and Jaakko Pallasvuo may not look obviously political at first glance, but they become political if one thinks that cultivating your own garden – meaning persistently cultivating, developing one’s artistic path – makes it radical and ethical, and thus, also a political gesture. The theme of cultivating one’s mind as a garden or a sanatorium is very present in the video Blue by Jaakko Pallasvuo, as well as in the VR work by Gailė Cijūnaitytė titled FEELS SO REAL! Binaural ASMR personal attention while WHISPERING and in other works. I’ll also discuss them in other answers.

Laura Kaminskaitė. “Sugar Entertainment”. 2011– (ongoing). Sugar (1.5 cm3)

And last but not least, I chose the allegories because they fit well into the architectural framework of this exhibition, which spatially looks like a labyrinthine system of caves with an exit into a garden. Selected works are very much about projections, ideology, and cultivation, be it inside or outside of your head.

The exhibition is focused on art created in Central and Eastern Europe within the last two decades. What is specific about the art from this region? How does it distinguish itself from the art created in Western Europe?

A few things. First, it is obvious that our so-called former Eastern European societies demonstrate a lack of conceptualising a future that would be radically different from our present. And we can’t waste time on holding on to the status quo. Think of the crisis of democracy, human rights, and xenophobic governments in Poland or Hungary, the demonstrations in Belarus, Ukraine, Russia, etc. Since our societies became part of NATO and the EU after fulfilling the formal requirements to enter these institutions, there has been a rather dominant nationalistic vision of increasing GDP and enforcing values that are anti-immigrant, anti-LGBT, and that extol ‘family values’ and so on. Thus, for this exhibition I wanted to present some retrospective works that portray our societies and their members since the 2000s and that reveal them in a not altogether progressive light, i.e. they are diverse, controversial (to say the least), sometimes dark, depressive, changing, evolving, and have problems with the past and with the contemporary world at large. For example, I noticed that even regional thinkers have difficulties addressing or talking about the BLM movement, the School Strike for Climate, etc.

Darius Žiūra. “Gustoniai”. 2001-ongoing. 6-channel video installation

Darius Žiūra. “Gustoniai”. 2001-ongoing. 6-channel video installation

However, in the age of global communication and travelling, even during our periods of quarantine it is problematic to divide art according to geographies, although some artworks do contain exclusively local topics and portraits that are unique and therefore may be characterised as belonging to a certain region. For example, the longest time-spanning project in the exhibition is a six-channel video by Lithuanian artist Darius Žiūra titled Gustoniai (2001-ongoing). Since 2001, every three years he goes back to the small village of Gustoniai, where he grew up, and makes one-minute silent video portraits of all its inhabitants. Black screens stand for the dead, the not-yet-born, or the absent. The video project is about the last 20 years in the life and development of a small community – how its members are growing up and growing old, leaving and returning, thriving and declining. At the same time, it’s a work about the video medium itself.

Artūras Raila. “Under the Flag”. 1999-2015. Video, 00:20:00. 2 channel digital video, color, sound

The video of another Lithuanian artist, Artūras Raila, titled Under the Flag (1999-2015), shows that fascism is still present in the post-soviet mentality as it reveals this far-right thinking and how it is structured. The story of the filming and the video itself is frighteningly arresting – in the video, leaders of some unofficial Lithuanian neo-Nazi party express their fascination with the Austrian politician Jörg Haider. In doing so, they expose themselves – on a platform provided by the artist – to the public. Although the artist did not organise the scene at the party headquarters, and the participants had agreed to be filmed and were even given some control over how they appeared, they did not like the final result. The leader of the party stated that he would not allow the film to be shown in Lithuania.

Eastern European societies quite frequently refuse to acknowledge that they are an active part of the larger world (for example, for xenophobic or racist reasons), and are introverted and closed in their own nationalistic state policies, so I also felt the urge to include artists and works stemming from outside of the region who talk about the interconnectivity of this world. For example, Jumana Manna’s (who was born in Palestine) video Wild relatives is about the links between ecology (global warming and seed banks, for example) and socioeconomic systems (the war in Syria and its causes and effects, as just another example).

Artur Żmijewski. “Glimpse”. 2017. Single channel video transferred from 16 mm, b/w, no sound, 14 min.

In Donna Kukama’s video Not Yet (And Nobody Knows Why Not) (2008), we see the artist standing in an open field in Nairobi as participants leave a meeting celebrating Kenya’s Mau Mau uprising against the British colonists in the 1950s. She starts putting on lipstick and paints her whole face in blood red. The question the film raises is why has Kenyan society not yet become secure and equal? This is the same question quite a few Eastern European countries also raise, especially when talking about minorities. Glimpses by Artur Žmijevski’s is about just that – our relationship with immigrants, our relationship with the so-called ‘other’.

In his interview with Arterritory, the German American anthropologist Tobias Rees said that ‘the political certainties that organised the Western world since the end of the Second World War have dramatically fallen apart over the past few years. Brexit and the election of Trump are powerful but are in no way the only indicators.’ What do you think? Is there a possibility that the geographical zoning of the global art world – in which the centre of gravity/power was located in the West – is falling apart? Especially within the current crisis raised by Covid-19.

The whole world changed without looking back during the last three decades, not just the so-called western world. The world became global, although this does not mean that it is equally distributed as the centres of power/gravity of the art world are (what a pity) closely related to capital and its movement.

The contemporary art world, at least globally, is closely related to its commercial side, whereas in so-called former Eastern Europe the commercial side isn’t all that evolved. We have very few successful commercial galleries, very few collectors, and our funding bodies are not that rich, all of which, on one hand, makes the artists’ lives more difficult. However, on the other hand, it allows artists to create without the pressure of being financially successful. Thus, talking speculatively, there is more art created that is sincere rather than produced just to fulfill the needs of the art market.

Gailė Cijūnaitytė. “FEELS SO REAL! Binaural ASMR personal attention while WHISPERING”. 2020. VR installation. Tomas Daukša. “No Limit”. 2019. Various sizes, plastic, rubber, foam, hot glue, artificial fur, aerosol paint, metal, LED lights, sound. Various locations throughout the exhibition

Do you have a vision of what the future/post-pandemic art scene will look like? What will be the main shifts be and to which direction will they shift?

For the sake of clarity, let’s stay regional in this discussion. If we are talking about creating/giving power in/to the regional art world, then we need to talk not just about contacts and representation of how the region is seen abroad, but more about empowering grass-rooted critical thinking, the production of knowledge, addressing the general lack of regional supranational publishing, reforms in educational system, superficial art criticism, the supporting of artists, etc. The power we may create should be about respect and understanding local artists and audiences in ways that transcend national boundaries; it should be about being united and progressive – advocating socio-political reforms, reconnecting to our societies, and reestablishing relations with general audiences. Generally, I’d like to see growth in the whole ecological system of contemporary art – it is important to have larger public and private museums, galleries, and smaller artistic and curatorial initiatives, but there is also a need for supranational publishing enterprises and art criticism.

And yes, Covid-19 may help us to achieve it now as there is an objective reason to invest more into local projects, into new online services and products.

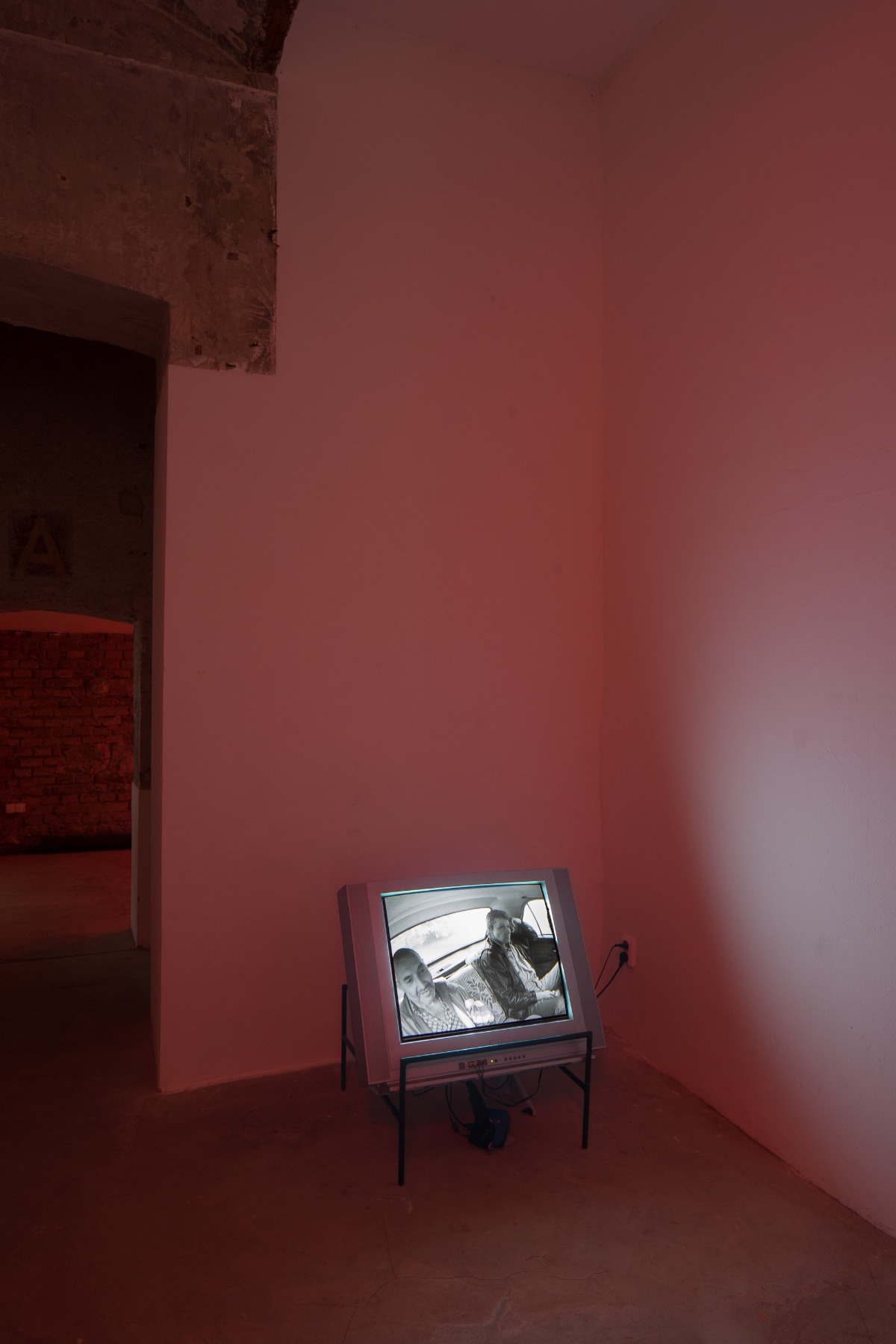

Katrīna Neiburga. “Traffic”. 2003. 18 mins., video installation

What is the task of art in today’s world?

The answer depends on what one calls ‘today’, and what one calls ‘reality’, which, at least to me, is far from being clear. According to forecasts, almost 40% of the world’s countries will witness civil unrest in 2020. There are more questions than answers. When will the world be free from quarantine, and what will it look like after it? What will happen in 2021? Climate change may bring about the end of civilization as we know it – according to calculations, within three decades. Thus, we and the whole world are seemingly running out of time. Change – in our society, economy, politics, you name it, and, of course, the art system – is inevitable. However, we all lack vision; we lack the new vocabulary and new political structures to talk about the future for all of us, even about the near future. This is what the art world may help with – artists, critics, historians and curators might help societies create new meaningful visions of the worlds to come.

Uli Golub. “Babushka in space”. 2017, video 00:23:46; HD 1920:1080, 24 fps; color, stereo sound, English subtitles

However, first we need to restructure the art world, to reinvent its new ecosystem, and I believe this is already happening. Art is always ahead, sometimes even too far ahead to compare to the rest of society. Thus, in the next few years, I wish for us all to catch up and move forward together (smiling).