Different approaches to Eastern European identity

Q&A with Maria Helen Känd, the curator of the ida ots(as)?/east end(s)? exhibition in Tallinn

The ida ots(as)?/east end(s)? exhibition dedicated to exploring the current situation regarding Eastern European identity, is on show until August 30 in the 5th hangar of the Põhjala Factory in Tallinn’s former industrial area of Kopli. Within the framework of the exhibition, eight Estonian artists (Alexei Gordin, Madlen Hirtentreu, Flo Kasearu, Sandra Kosorotova, Tanja Muravskaja, Marko Mäetamm, Evi Pärn, Tanel Rander) are presenting their works of art in diverse mediums, thereby creating a complex offering for an open dialogue. The exhibition re-examines and reflects on the socio-psychological experiences of Eastern Europeans and the international image of Eastern Europe.

According to the exhibition’s press release: “Estonia is in the process of finding its identity as a progressive nation with roots in folklore, whilst having to accept the disruption of the time under Soviet occupation. Yet, the process of redefining identity does not come with stability and it is not understood unanimously, because of economic inequality, and a number of historical traumas. In order to be overcome, these traumas need a collective sense of a strong social structure, which is formed by the state and its citizens. At the same time, the nation needs to open up to the global community to evolve and ensure its continuation.

Existing tensions generate both inner conflicts and creative impulses. Artists and their media present different perspectives to address the issues of identity, which is the key focus of this exhibition. The title entails socio-geographic, temporal and psychological aspects of borders. Is Estonia the final frontier of ‘the East’? How is Estonia’s identity shaped by inner and outer expectations? Do we need to pursue the set of economic, societal and developmental standards of Western Europe or do we have the backbone to define a new path? The exhibition doesn’t just invite audiences to accept their complex identity, but will also offer the possibility to find a new personal interpretation.”

Arterritory.com spoke with the exhibition’s curator, Maria Helen Känd.

How can you characterise your own identity?

I would characterise myself through my work, values and interests. I believe it is common for people to identify with their creative, intellectual or other professional work. The national aspect becomes relevant in an encounter with others; for example, in an international context I would mention that I come from Estonia. The self-image that is created in relation to people from other cultures, specifically with the “West”, is one of the key topics of this exhibition.

Regarding myself, I’ve considered the post-1991 context I grew up in and historical situatedness to be one of the defining aspects of my identity, and this includes my national identity. Having been born in the free Republic of Estonia, I was raised to be proud of what our country had achieved in this short time of independence and the of culture that we managed to keep alive during the occupation. I would say that my generation – a new generation that has been able to travel and be educated all around the world – was brought up with a certain responsibility to represent our country of only 1.3 million people. Having studied abroad myself, I have plenty of experience explaining that the Baltic states are not Balkan states and that Estonia is not a strange place without television on the periphery of Europe.

Flo Kasearu. International Fun. 2016. Photo: Felix Laasmäe

Later on, after high school, I started to deconstruct this self-image and analyse my national and historical background more critically. Through this process I could also detach myself from different roles and narratives of the Estonian national identity concept, for instance, the concept of historical trauma. However, the responsibility remains; one has to engage in societal matters and contribute to the establishment of equality and freedom. So, of course, I care about what’s going on in my country and acknowledge its problems.

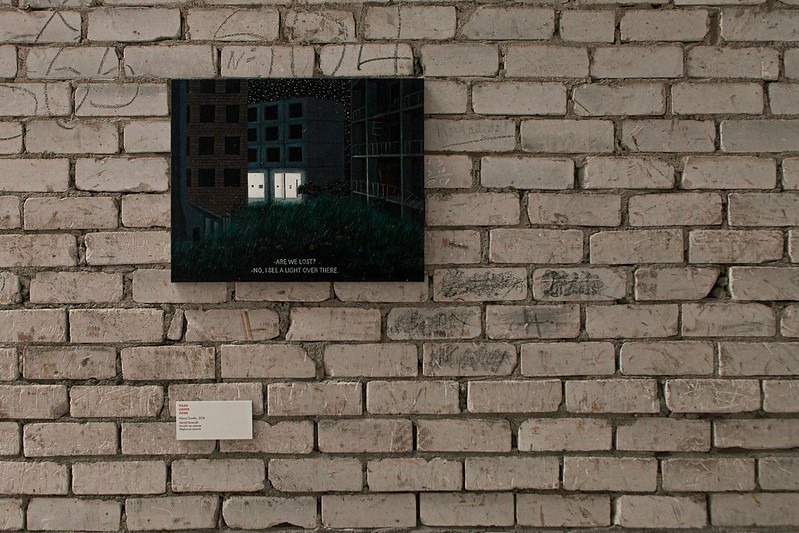

Alexei Gordin. Lights. Acrylic on canvas. 2018. Photo: Felix Laasmäe

There are many topics the people in Estonia need to be watchful of that are related to the current political trends. The profit-oriented and short-sighted forestry policy, ignorance towards climate change, attempts to diminish the legitimacy of ethnic and gender minorities as well as NGOs – these are all clear examples of that.

Alexei Gordin. Between the Past and the Cosmos I and II. Acrylic on canvas. 2013. Photo: Felix Laasmäe

What defines the nation’s identity, and why did you feel the importance to raise the question of Estonian identity via this exhibition exactly at this moment in time?

The shared ideas that constitute the narrative and image of a nation are not fixed or stable. Still, some of them tend to change more slowly than others. Benedict Anderson’s concept of “imagined communities” captures well the necessary conditions for the shared feeling of national identity to emerge and hold, which, according to him, was the invention of print media in national languages that created the understanding of a community, although the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow members or have much in common with all of them.

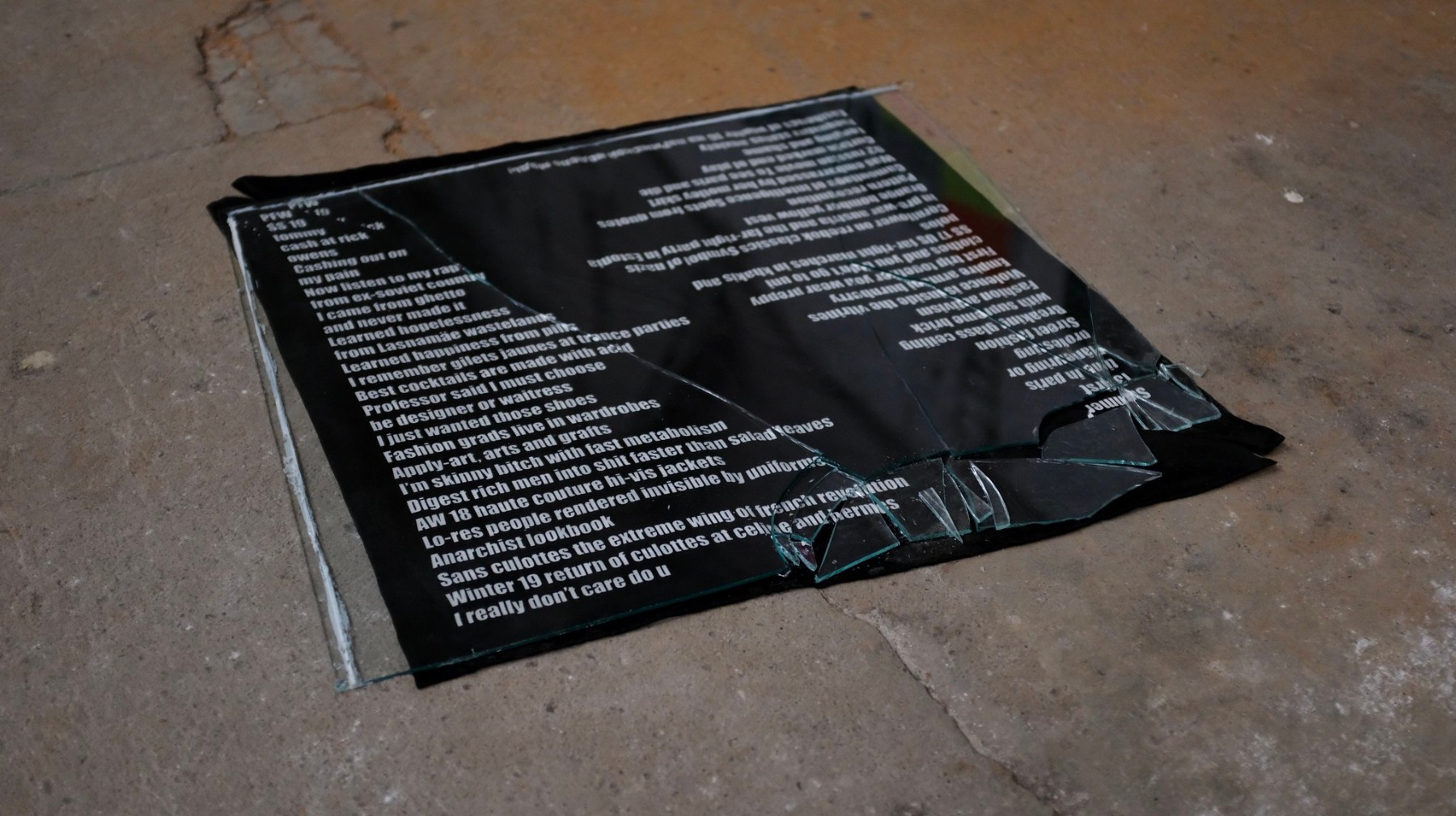

From floor:

Flo Kasearu

International Fun. 2016

Tanel Rander

Nostalgia from series "Guillotine Effect". Digitally reproduced charcoal drawing print on textile. 2016

Sandra Kosorotova

Slavinavia. Digital print. 2013.

Photo: Felix Laasmäe

Even if I refer to Anderson’s social constructivist approach, I think it’s important to acknowledge that the fact that national identity is constructed historically and politically does not make it less significant and meaningful for people. That’s why there’s a continuing need for self-determination and discussion about (national) identity in today’s global, interconnected world.

Clearly, the understanding of national identity varies within Estonian society and amongst the people living here. The aim of this exhibition is to show different approaches to the Estonian and Eastern European identity without denying the problems that still exist in a small country that has been independent and again open to the world for merely thirty years. The exhibition addresses the challenges that stem from the need to be recognised from the outside as an independent country and individual, such as in the works by Marko Mäetamm and Flo Kasearu, but also touches upon internal societal dilemmas in Alexei Gordin’s, Evi Pärn’s and Sandra Kosorotova’s approaches. Madlen Hirtentreu and Tanel Rander take an intellectual yet playful, even ironic, stance towards the past. There are also works that more generally explore the relationship between the individual and its ideological context, such as in Tanja Muravskaja’s series of photographs and installation that question the possibility of moving to the future with or without a historical background.

Works by Flo Kasearu, Tanel Rander, Tanja Muravskaja. Photo: Felix Laasmäe

One of the reasons for doing this exhibition now is that the topic of national identity and the use of national imagery has been hijacked by extreme right-wing conservatives since their emergence on the Estonian political scene in 2014–15, which as been strengthened by their current position in the government. We need a much more diverse conversation about national identity than they or their political counterparts have to offer. So, I reckon that in art (and also film, theatre, etc.) there is a possibility to hold this conversation in a more abstract and sensitive way.

Secondly, nowadays in Europe there still seem to exist normative divides between the “former West” and the “former East”, even on an actual political level. Stigmatisation is very alive and kicking, as shown also by the political slogans of nationalist conservative parties in Western Europe on the issue of internal EU migration. Of course, there are many more complex problems related to serious ongoing crises such as the war in Ukraine, the BLM movement and the situation in Belarus, but I think we should also acknowledge the complexity of Europe with its different regions. Ignoring these smaller narratives and issues that are relevant for people further away from “the centre” are some of the direct causes of disappointment and the rise of the far right.

Marko Mäetamm. Estonians. Acrylic on paper. 2017. Photo: Felix Laasmäe

That reminds me of Alina Bliumis’ work In the Centre of Europe (currently on show at Tallinn Art Hall[1]), in which she reveals the story of Europe’s former borders and new borders. The work focuses on the central points of Europe by various measurements and reveals, paradoxically, that while the centre of power lies in the West, Europe’s geographical centre is located further east than one would expect.

All in all, I felt the need to open up a dialogue on the questions relevant for our society, the external expectations set on us, and how they can be met in a post-Soviet society.

The central motif of the exhibition is the potato. In the curatorial statement you write: “The potato is ironical, while it is connected to poorness and a certain simplicity, it never loses that earnest, emblematic characteristic of austerity and strength.” Ironically, as we know, the potato is originally from South America and was brought to Europe by Spanish conquerors in the 16th century. As historian William H. McNeill stated, the potato in some way fueled the rise of the West: “By feeding rapidly growing populations, (the potato) permitted a handful of European nations to assert domination over most of the world between 1750 and 1950.” So, the identity of the potato itself is quite complicated and closely related to colonial history. Were you aware of this aspect when you chose the potato as the symbol of the exhibition?

The potato as a symbol in the works presented in the exhibition conveys different meanings. In one of those works, The Strategic Planning of Transformation, Tanel Rander critically approaches the topic of colonisation in the Baltic states and the role of the Baltic-German noblemen introducing their culture and values to the Estonian peasants, who were serfs until 1819 and suffered under foreign domination. So, I was indeed aware of the history and of the reasons and means how the potato was brought to colonised regions all around the world, including the lands of the Estonian and Livonian people in the former Russian Empire.

Alexei Gordin. Spring. Acrylic on canvas. 2019. Photo: Felix Laasmäe

The precise reason for choosing the potato as the central motif is that in local history and in the works of art presented, it links to different historical periods that still influence the way the people here perceive the identity narrative, for example, the time of serfdom that in the collective consciousness is captured by the metaphor of “700 years of darkness”. Also the Soviet period, as in the sculpture installation Basic Pride II by Flo Kasearu, which refers to Estonia as one of the leading countries for potato production, known in the Soviet Union as the Potato Republic. More recently, there was the time of the independence revolution in the 1980s, when the yearning for freedom was so strong that this shared feeling of endurance led to the common saying of “being willing to eat potato peels”, meaning that the Estonian people were ready to endure absolute poverty in order to attain freedom.

Since Estonia became a part of the European Union, it has been promoted as a digital success story and a tech-savvy nation. Now, as mentioned in your curator statement, “Estonia is in the process of finding its identity as an open-minded progressive nation with roots in folklore, whilst having to accept the disruption of the time under Soviet occupation.” National identity is a social construct, determined by history. Do you feel the story of the Estonians as a tech-savvy nation is misinterpreted in some way? Is it more a stereotype than a part of Estonian identity?

In my curatorial statement I did not intend to minimise the effort and outcomes of digital development, but instead to highlight that there are still acute societal problems and inequalities that have not been and, of course, cannot be solved by digital solutions only. Estonia indeed went through this rapid digitisation. Even now, during the Covid-19 lockdown, our schools managed to function well due to this digitisation of education.

However, there is still a digital divide between the older and younger generations. There are also issues such as the biggest gender pay gap in the EU, the relative poverty of a quarter of Estonia’s population, and problems related to the integration of non-Estonian speaking communities. The latter was brilliantly brought up in a recent speech by the young Russian-Estonian choreographer and poet Sveta Grigorjeva at the president’s reception on Estonia’s Restoration of Independence Day (Taasiseseisvumispäev) on August 20.[2]

Madlen Hirtentreu. A trembling piece of lard. 2020. Photo: Alissa Šnaider

Instead of debating whether Estonia is or is not the most advanced digital country in the world, we should consider whether technological pragmatism can be the single, overarching enabler of a more cohesive and equal society. Here lies the effort to fill the signifier of cultural identity – something that can hardly be done by digital solutions. I’m not talking about Estonian cultural identity in a national sense, but in general; I’m talking about whether e-Estonia entails values and emotional qualities that can unite people living here, regardless of nationality.

Identity is in constant flux. It is not stable, because it is closely connected not only with one’s history and upbringing but also with the choices one’s makes in life. As any construct, it has a dose of utopia in it. What role does the notion of border play in the process of forming identity?

Borders that constitute the understanding of one’s identity are multiple: geographical, social, psychological, temporal. There’s a reason why nations or peoples claim and strive for their identity by the ideological and political reassurance of a certain territory. It provides them with safety and a geographical image. For example, indigenous people – no matter whether in Latin America or Siberia – struggle to protect their traditions, environment and community without the legal structure of a border. That’s not to say that the modern nation state with borders is the only and right way to establish a sense of identity, but in a world where markets and superpowers regulate everything, it’s difficult to survive without the recognition of territory. Amongst the Finno-Ugrian indigenous peoples, Finland, Hungary and Estonia are the only ones that have their own state. Unfortunately, the others have struggled a lot to hold their communities together and keep their traditions alive. Some have vanished altogether.

Tanja Muravskaja

Positsioonid, Positions. Digital print. 4 photos from a series of 7 photos.

2007. Photo: Maria Helen Känd

We saw with the worldwide pandemic how borders suddenly became decisive again, and even within the EU, the borderless cooperation failed. People were suddenly reminded of borders again, and fears and stereotypes were fueled by the media. Unfortunately, the coronavirus also made it possible to use the virus to carry out political measures that allow discrimination, for instance, against foreigners.

One of my favourite Estonian novels is Tõnu Õnnepalu’s Border State (published in 1993). It’s a wonderful account of the unending renewal of the self and the search for identity after the change of political regimes. The narrator finds himself in liminality, crossing temporal and geographical borders after the collapse of the USSR, which results in a psychological crisis. Boris Buden argues that Europe is not only divided geographically but also temporally, where the “East” remains belated and is treated a-historically in the Western framework.[3] So, in Õnnepalu’s novel, similarly to the recently liberated Eastern European country, the narrator also tries to establish a new identity – an a-historical self that would have no ties to the Soviet past and would have historical relatedness to the time-space of old Europe. It’s a “return to Europe” that fails because “Europe does not recognise him as someone returning”, as the literary theorist Eneken Laanes puts it.[4] I brought up this example because the novel brilliantly demonstrates how the different aspects of borders co-formulate identity.

Sandra Kosorotova. Bananas. Digital print on silk. 2019. Photo: Maria Helen Känd

“The world will never be the same again...” We’ve heard that many times since the pandemic began. Do you think Covid-19 and how the nation deals with it could leave a mark on Estonian identity?

I hope that one realisation this pandemic brings us – aside from the uselessness of consumerism – is that great projects can be carried out locally. We don’t always have to look far away to work creatively. In European regions, such as northeastern Europe, which want to build cooperation with capitals like London, Paris and New York, there’s a sudden situation in which work has to be done with neighbouring cities. I think it would only do us good to also appreciate and get to know more about what’s happening in Kaunas, Riga and Saint Petersburg. It will surely change our perspective and view on things.

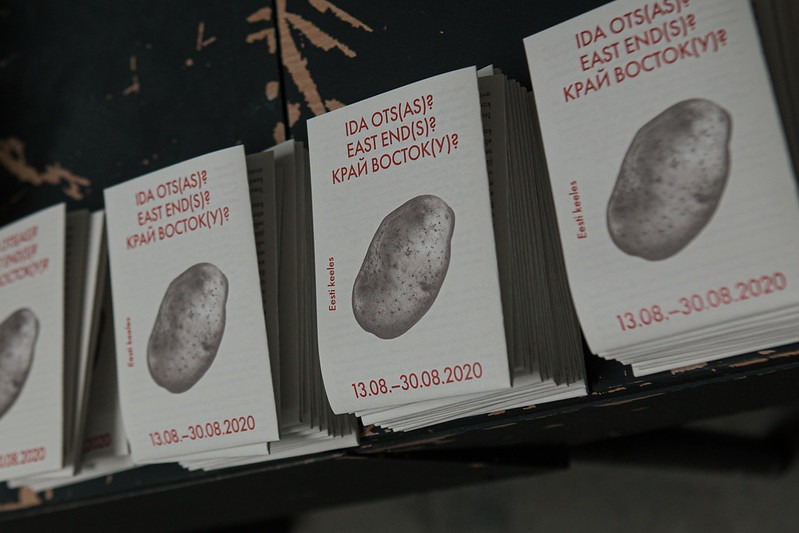

The booklet. Graphic design: Henri Kutsar. Photo: Felix Laasmäe

[1] https://digigiid.ee/en/exhibitions/alina-bliumis-and-tanja-muravskaja-narrating-against-the-grain

[2] https://news.err.ee/1126215/sveta-grigorjeva-i-dream-of-a-country-where-everyone-can-dream-big

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D88bfYfb_68

[4] Laanes, Eneken. “Confession: Performative Production of Gender and Memory in Tõnu Õnnepalu’s Border State”. In: Iterationen: Geschlecht im kulturellen Gedächtnis, edited by Anja Schwarz and Sabine Lucia Müller. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2008.