Mare Vint: In search of the ideal landscape

An express interview with curator Francesco Tenaglia

Mare Vint (1942-2020) was an Estonian graphic artist whose work largely focused on the depiction of “ideal landscapes” – in her attempt to capture the perfect synthesis between nature and man-made structures, she created scenes that appear familiar to the viewer but which do not exist in reality. Starting with 22 January, a solo show featuring Vint’s work, titled “Nothing but Time”, will be on view at the non-profit, artist-run space Goswell Road in Paris. Vint’s emergence in the late 1960s coincided with changes in the strict political regime of the Soviet Union, an event that also brought about a shift in the Estonian art scene. Vint was part of the local avant-garde movement, which had close connections to the Russian underground artists of the era. During the 1970s and 80s, Vint participated extensively in international biennials, despite the fact that the Soviet Union prohibited artists from sending their works abroad.

“Nothing but Time” is being produced and organised in collaboration with the Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art, and curated by Francesco Tenaglia, the artistic director of Sgomento Zurigo exhibition space (Zurich) and author of cultural articles for both Italian and international magazines. Tenaglia is on the board of the non-profit space Almanac Projects (London and Turin), and teaches Critical Writing at the Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan.

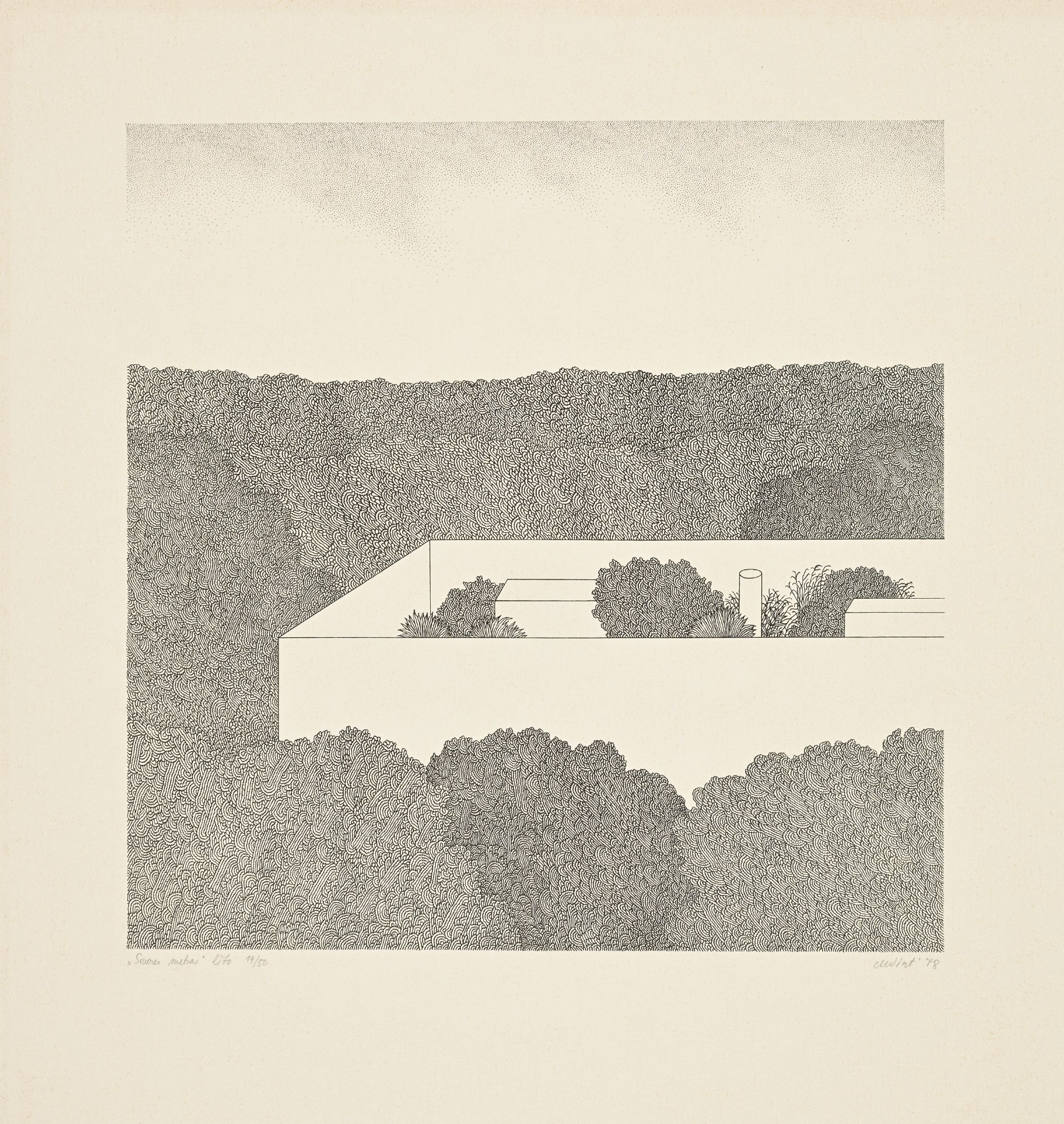

Mare Vint. In a big forest. Litography, paper. 1978. © Art Museum of Estonia

There are not many curators from abroad who research art and artists from the Baltic region during the Soviet period. How did you find out about Mare Vint?

Yes; fortunately, we have the opportunity to live in a period in which lovers and scholars of contemporary art (either academically or otherwise) can research beyond canonical or the usual national boundaries. Of course, I am not referring specifically to the artistic practices of the Baltic countries, but to the fact that in the discourse of contemporary art, discussing the ideas of “centrality” and “the peripheral” have become a priority; people are more concerned with the fact that social, political and cultural ramifications have been reflected – sometimes in problematic ways – in the visual arts more than in idealistic conceptions of art making. The growing awareness that there are no privileged “points of view”, or “objective” or “monolithic” stories, seems to me a good start. I must confess, however, that my interest in Mare Vint arose in a more simple way: I was editor-in-chief of a contemporary art magazine called Mousse, and one of our contributors – the American Andrew Berardini, whom I regard as one of the most remarkable and talented writers around today – started telling me about Mare Vint. Vint's art impressed me a lot, and I kept on going back to her work and immersed myself in her practice and, after a period of research – here we are.

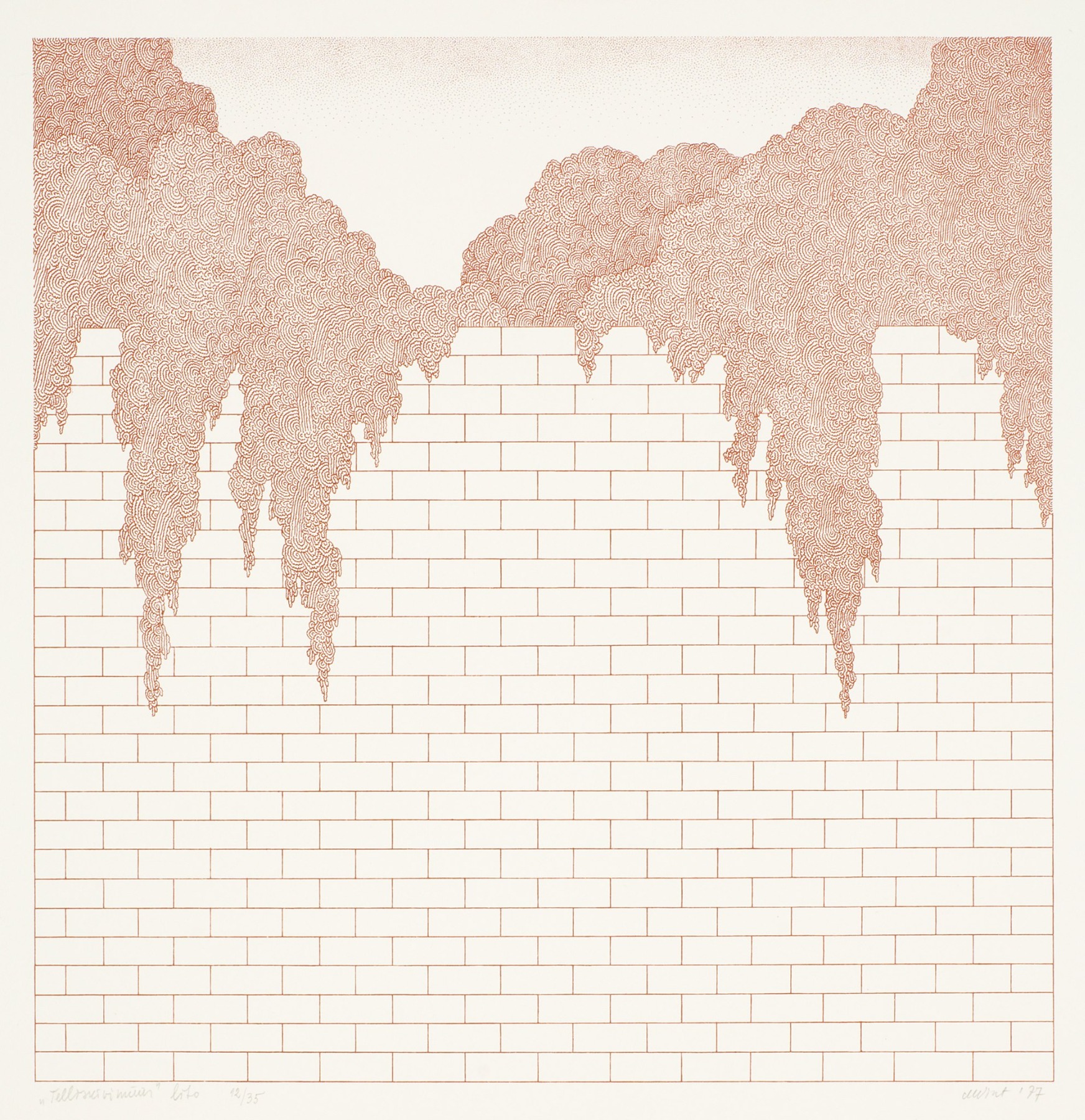

Mare Vint. Brick wall. 1977. Lithography, paperr, 62.1 x 60.2 cm © Art Museum of Estonia

How does her art fit into the framework of 20th-century art history beyond the Baltics and Eastern Europe? Have you found in her oeuvre something very specific, something that occurred and developed because of the place and region where she was born and where she spent her life?

I believe it is only natural that artistic practice is informed by the conditions in which a particular person finds herself operating – from the things she sees, the people she talks to, the information she learns in school. The idea of an autonomous talent, completely divorced from society, belongs to other periods. I realise that the idea of searching for an ideal landscape – one which harmoniously marries human presence with that of nature – can only refer to considering the realisation of a utopian society in the distant past (and using visual references from this past), while acknowledging the fallibility of the one in place during one’s lifetime. More simply, in Vint’s landscapes – in the interrupted perspectives, in the structures that often refer to the idea of a labyrinth or an apparatus for containment – many read a reference to the Soviet era. However, it must also be taken into account that the conditions that inspired many paintings of the past are often unknown to the viewer – battles, revolts, specific historical events – including the gestures and postures of figures which can be very difficult to decipher. Although it is essential to know these conditions to understand the work of an author, there is always a perspective that exceeds the "realism”, the strict actuality. By overcoming the concerns that animated the creation of a work, we can grasp an articulation, a point of view, a reading that makes an artist a great artist.

Mare Vint. Four woman. 1977. Indian ink, paper, 41.5 x 40.7 cm © Art Museum of Estonia

The focus of her art is the “ideal landscape”, the search for harmony between man-made structures and nature. How does she reach her goal? What is harmony for her? How should we look at her art so we don’t miss something?

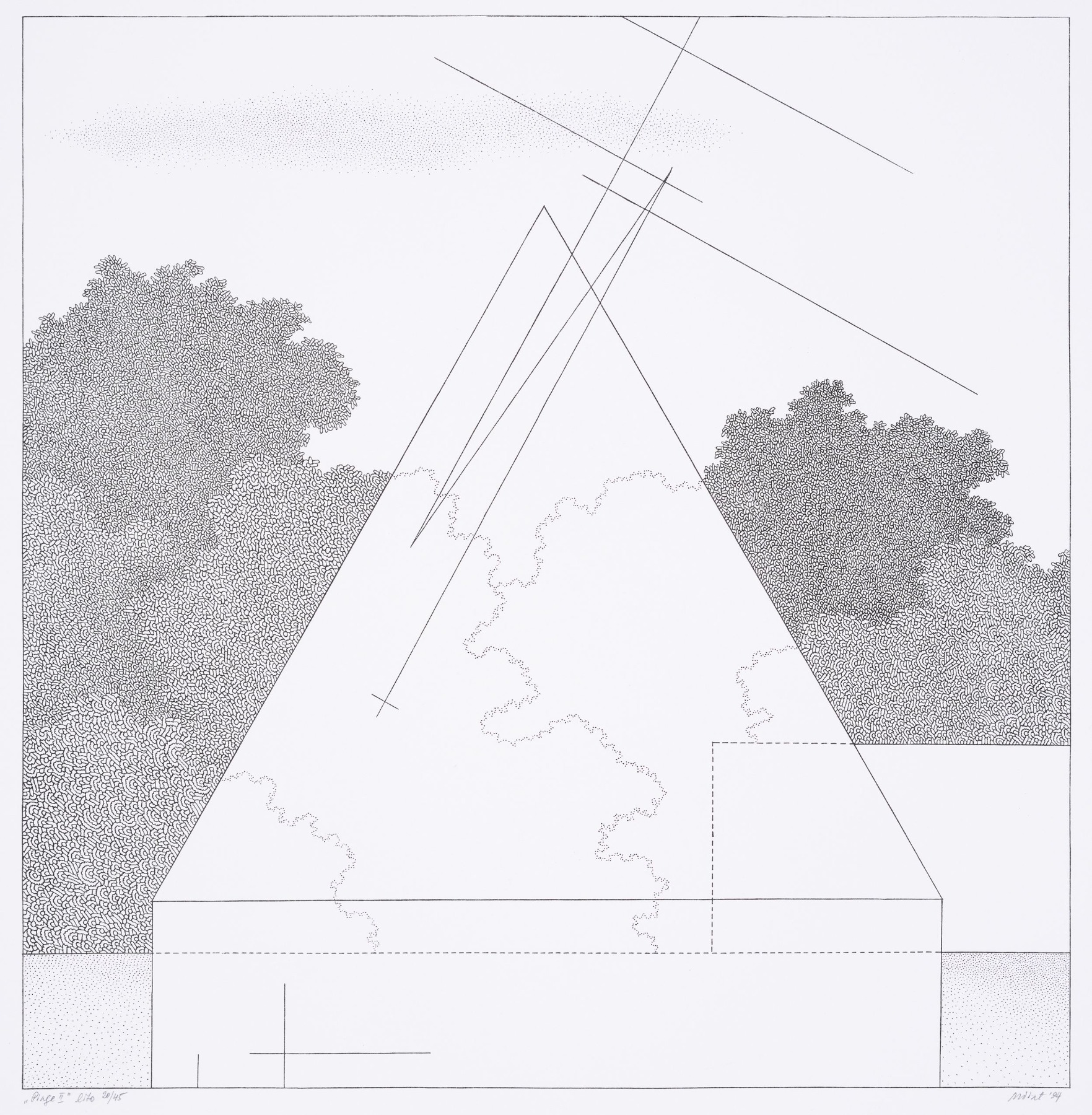

It is very interesting: although these are "ideal” scenarios, it is clear that Mare Vint included elements linked to very personal interests, so the emotional value of the recurring elements in the works, in a certain sense, creates a rather unusual combination with these ideal landscapes that one would imagine “universal” or “objective”. Furthermore, it seems to me that one of the phases in her career is that in which she represents reality by superimposing the realist sign with analytical, almost technically geometric lines. As if the abstract plane of the figuration overlapped with the figurative one in a touching of parallel universes. Another absolutely charismatic element is the presence of architectural elements which, at times, seem not to respond to the criteria of human habitability, like puzzling mazes – as if the implied gaze of the observer of the oeuvres came from a remote time or from a world that does not necessarily correspond to ours.

Mare Vint. Tension II. 1995. Lithography, paper, 42 x 41 cm © Art Museum of Estonia

Mare Vint used to mainly work on paper; only when nearing the end of her life did she begin to work on canvas. How did this change her ideal landscape?

The later works are, at times, very touching to me. They look like glimpses of places seen in the distant past. The very refined use of colour gives them an atmosphere that is difficult to describe for those who have not had the opportunity to see them in real life. In other cases, the geometric dimension of the architectural and landscape structures becomes almost sibylline. I believe that the artist's research has moved towards a simplification of forms which, however, corresponds to a rarefaction of ideas and a look that become almost inscrutable.

What is your curatorial leitmotif for the Mare Vint exhibition at the Goswell Road space? How did you build the show?

The basic idea of the Goswell Road exhibition is to present a dialogue between a selection of works from different periods of production for a new audience. It is an intimate exhibition, one which does not have the ambition to historically represent Mare Vint's work, but undoubtedly does contribute to presenting her work in the context of an independent space that attracts a young audience that is attentive to international trends and subcultures, as well as French curators and media. I hope it can be an exhibition that, within its scope, can be made functional to a necessary retrospective in the future. The criteria used for selecting the works were very personal: during a research trip that I was lucky enough to take in Tallinn during the summer (with the support of CCA Estonia), these works are the ones that I responded to the most and that I felt went well together with one another.

Mare Vint. Balcony. 1973. Lithography, paper. 60.3 x 56 cm © Art Museum of Estonia

What is an ideal landscape for you? Is it possible to find harmony in today's world – a world that was very hectic before the pandemic and that is very tense at the moment? Do you think that art could help people live through all of this?

Unfortunately, I was born in a time when urbanisation was considered the highest level that one should aspire to, so subconsciously, my ideal landscape is an urban landscape. I must say that, being Italian, I grew up in cities designed around places of civic use – the town hall, the church, the square, the market – and that I gave great importance to perspective and how the city was presented. So certainly, my ideal landscape is a city, and wandering around a city. Probably the current health alert will transform cities in the medium term, but at the moment, for me the ideal landscape is made of buildings and streets.

Mare Vint's solo exhibition “Nothing but Time” at Goswell Road, Paris