Constructions inspired by change

An express conversation with artist Kristaps Ancāns

Reactions and opinions on how the past year has affected the development of the visual arts and artists' individual practices are, one might say, sharply divergent – for some it has proven to be a successful time in which to develop pet projects, while for others, work has come to a complete halt. Rare is the individual who can say that, despite the impact of global events, in 2020 it was possible to keep one’s head above water and completely compensate for all cancelled or failed plans with other projects. Latvian artist Kristaps Ancāns appears to be one of these anomalies who have managed to achieve success, and not only in terms of participating in international exhibition projects, but also by taking on a position at the Estonian Academy of Arts as one of the heads of the Contemporary Art programme. Ancāns says that the art world was shaken up last year, and it is important to take this into account when thinking about changes in the art environment and related social constructions, both in the near term and further into the future.

Kristaps Ancāns

Many artists cite 2020 as one of the most productive of their careers. How has the last year been for you?

In the art world we had known up to know, there had been no such thing as a bad or unproductive year. The impression was that everything was always ‘great’ for everyone, regardless of whether you were an emerging artist or an experienced artist, a gallery or an institution; that’s because if things were not always ‘great’, doubts would be sown about how successful – or even talented – you really were. No matter how amusing, strange, or inane it may now seem, such dogmas characterised the art world in Latvia and, at least partly, internationally as well.

The profession of being an artist does not guarantee stability, income, success, recognition or employment. 2020 certainly was a healthy year for the art community because it removed a kind of pressure; everyone had the same global reason to catch their breath – if something failed, there was something to blame. I would not say the last year was unproductive, but, just as this one is turning out to be, it was unpredictable in terms of planning. All transatlantic projects are frozen right now, which is not a good thing because every work captures a certain time, desire and idea. Thoughts and ideas follow a sequential progression, and this year broke that sequence, so next year we will have to return to the works and ideas that were born and realised in the previous year. It is currently difficult to say whether this will affect the quality of these projects and their final outcome.

I also had to make difficult decisions regarding whether to exhibit works digitally or postpone the projects indefinitely. For example, the project with the Live Art Agency and the Tate Gallery from last year is still hanging in the air and without a precise date, as London is now in its third lockdown.

As there were no serious restrictions in Latvia for most of the year, I managed to exhibit a couple of physical projects here (at RIBOCA2 and Rīgas Mazākā galerija), although I could not physically participate in the installation of the works myself. I have more projects in Latvia that are awaiting the end of the lockdown. On the other hand, the last year was conducive to many ambitious projects of mine in the UK, which were catalysed by the fact that there was finally enough time for negotiations and discussions. Many of the projects that were seeded in 2020 will continue this year, such as the Bad Ideas Collective done in partnership with Five Years and Fallow Field, along with Meadow Arts.

This year led to analysis, which is not always a pleasant process since analysis identifies both successes and failures. Of course, it also indicates where there are shortcomings, as a complete analysis should cover the full spectrum. Nevertheless, the result provides a clear understanding of the situation.

Do these global changes encourage you to explore new topics in your work? What are the issues that currently occupy and interest you as an artist?

The changes did not lead me to focus on new topics, but, independently from us, the context of the topics changed as the world changed (and it is still changing – we cannot yet see the end result and its consequences). I am increasingly interested in the relationship between the indoors and the outdoors. In a way, I consider myself a constructor – I like to create an object or a text and see what this thing can become in relation to itself and in relation to the viewer. The viewer themself becomes a medium in relation to the work.

During the first lockdown I realised that this is a time to look back on my practice. I suggested to my peers that they go back to ideas that were never realised or were left by the wayside – ideas that never materialised not because of financial reasons, but due to self-critical reasons. We came up with a project called Bad Ideas Collective. We addressed young, newly graduated artists, as well as very well-known artists, and asked them to make a short video in which they illustrate and speak about what they once thought was a ‘bad’ idea. The project really drew us in and was also supported by Arts Council England; it is still evolving, and it is also beginning to develop into a kind of research study.

The second project, which we have been planning since early 2019, is called Fallow Field, and is coming together with Mark Dunhill and Tamiko O’Brien. We’re creating scenarios for the development of public art and we will start a residency in the summer that will finalise in an exhibition at the beginning of winter.

I think that this ‘earthquake’ in the art world was healthy, and hopefully it will bear very interesting fruit. Let's hope that the stage in which everyone learns what contemporary art should look like is over.

Screenshot from www.badideascollective.com

If I understand correctly, you are still spending most of your time in London. How have external conditions changed the art scene there, and are any long-term adjustments already being felt in terms of the topicality of certain subjects and in the activities of galleries and curators?

The art world has shown its fragility, and London is no exception. Every institution or gallery strives to help its artists, and this situation has certainly not benefited young artists who will be graduating from institutions of higher education in art this year. Art schools will have to put in a huge amount of work to support them. Art education is a very important export commodity, and schools are very loyal and serious about this process.

For Britain as a whole, this has not been a hit below the belt – this time around, things are more difficult for large institutions than for medium-sized and small institutions. In recent years there has been a great deal of pressure to streamline and create high-quality artistic environments on a local level, and this strategy has shown its advantages during Covid. With the help of institutions, support for artists was provided fairly evenly and it covered the entire country. The new Arts Council strategy was devised before the pandemic, and it defined its objectives very precisely with a very clear plan that created support programmes for both projects and individual practices.

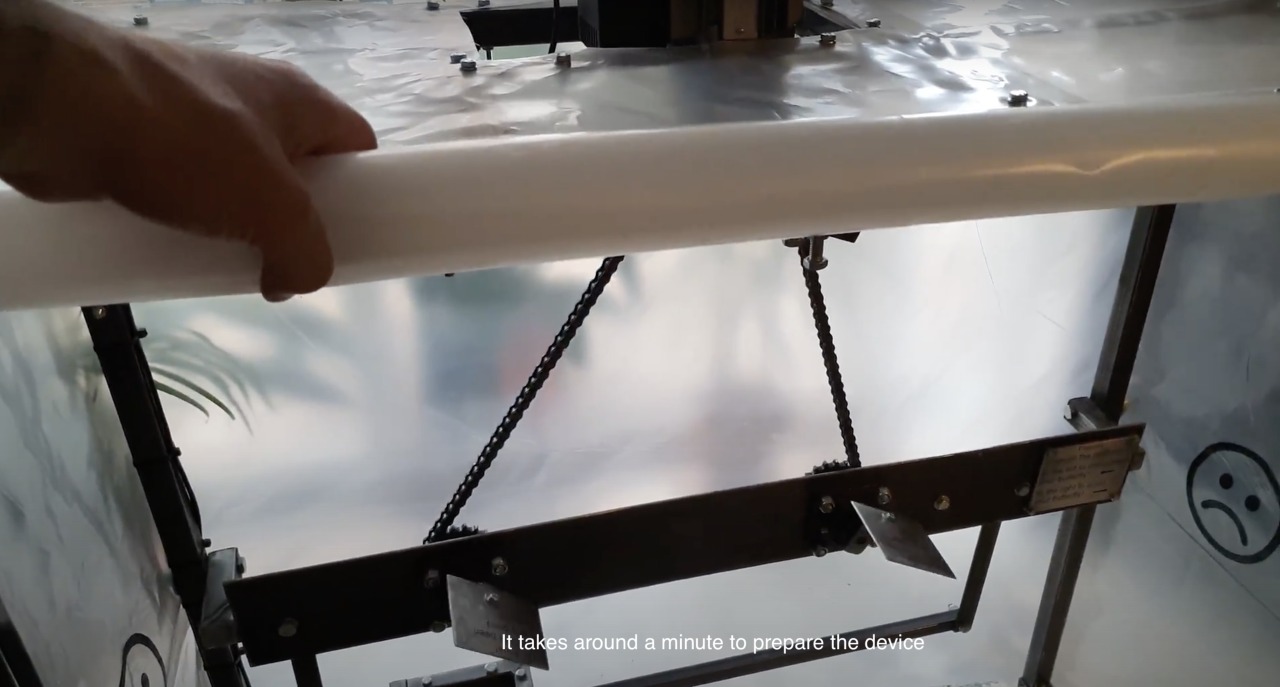

My work in London takes place in two studios – I call them the ‘clean’ one and the ‘dirty’ one. The clean studio is located in a building built especially for artists' workshops and it does not allow for any work that creates dust. The dirty studio, as its name suggests, is equipped for messy work. It’s a shared workshop space, so it's been shut down again. I had to go back to using hand tools (including non-electric ones) for cutting metal, filing it, and so on, and this made the process much more time consuming. However, this did give a kind of excitement and challenge to the whole thing – I even crafted a homemade mobile hand-powered hoist.

As I said before, decisions had to be made about exhibitions regarding whether they would take place on a digital platform or be postponed. Since both my two- and three-dimensional works are fairly large in size, I chose to wait because my work did not seem to fit well within a digital space. I believe that a work must be specially designed for this format in order to be successful. I remember a conversation I had with Mark Halson – his studio is on the other side of the park, and so we met and discussed digital galleries as a solution. He noted that it is quite an unusual feeling – the exhibition is going on, but your work is still in the studio.

Digital platforms offered a solution, but they came with their own rules. The digital format makes two-dimensional works even flatter, and it restricts them to a certain size – which means that you can't fully experience larger-format works unless you have a cinema-sized screen at home. Secondly, the relief of the image, its texture, our scale against the work – it all disappears, and content starts to dominate over form. We lose materiality, and content becomes number one. This will certainly have an impact on painting and graphic works if this situation continues much longer. The young artist Konstance Zariņa, who is currently studying at the Art Academy of Latvia, has conducted an interesting study on these topics, and she is preparing to give a public lecture on it in the near future. I recommend people go hear it.

There is also futuristic speculation that art could become a subscription service – not only at the institutional level, but in a much more accessible form. Such hypotheses are being put forward by large corporations not linked to art, but at present they are only thoughts and concepts for the future.

Different reasons why your snowman looks dirty, Rīgas Mazākā galerija. Photo from artist's archive

You’ve begun to actively participate in the academic field – you’re a lecturer at the Art Academy of Latvia and one of the heads of the Contemporary Art programme at the Estonian Academy of Arts. What is it about teaching that attracts and fascinates you the most?

I am fascinated by the potential, the constructs of thinking, the ideas, and what this potential – with certain support – can accomplish.

I believe that the Baltic art space has huge potential, and we are intensively building this infrastructure in both Estonia and Latvia. I believe that art academies have become the main starting point for the development of art. The region has existentionally important and strong art schools. Compared to the west, the Baltics carry a different type of cultural and historical baggage, one that gives us greater maneuverability.

It is very interesting to work with Mark Dunhill in Estonia because he was a dean at Central Saint Martins when I was a student there. It's a great experience to work on the programme together with him. In the last couple of years the programme has been able to attract strong students from all over the world – students who see the region as a great place to develop their practice – and which benefits more than just the academy. It is very important that new ideas and initiatives gain support, so I am pleased with the results we’ve achieved together with Kristaps Zariņš, Rector of the Art Academy of Latvia (AAL), and Antra Priede, Dean of the Master's Programme, as we’ve worked on several new structural units.

We have created a joint Master's study programme project together with Central Saint Martins College, which this year is focusing on art in the public space. On 28 January a series of public conversations began, which is the first stage of the project; it will continue with exhibition projects in London, as well as in Jūrmala, where we are cooperating with Art Station Dubulti.

Cooperation with London is also continuing in the new support programme for artists, curators and art historians who have graduated with a master's degree – it provides them with a two-year residency and support programme in London and Latvia. We’re building a bridge between higher art education and an international professional career. This programme has been created in cooperation with Latvian State Forests, the State Culture Capital Foundation of Latvia, and our partners in London.

The AAL is also developing an interdisciplinary international art department, which we are creating together with Gļebs Panteļejevs and Amanda Ziemele. The department will offer a new master's programe that is focused on artistic practice.

The Latvian and Estonian academies have set a strong course for development. In both Estonia and Latvia we have also come to the conclusion that art education cannot be the same as it was before the pandemic. We need to prepare students for real and current conditions – the art world took a shaking, and we are taking this into account. Academies not only provide an education, but have also taken on the role of building relationships between young artists and international and regional institutions.

How do you manage to balance your academic responsibilities with your creative work?

I perceive academic work as the research side of my practice, which then allows me to develop a more in-depth understanding of the creative process and its structure. Every conversation with a creative mind, be it mature or still developing, is an analysis of that person. You have the opportunity to constantly meet people who are trying to understand their construct of thinking, and, you are given free access to their minds – because you have to both give them the tools with which to find this understanding and be a part of that process yourself.

Even during the pandemic I have to travel a lot between countries, which, of course, does not allow me to spend as much time in the studio as I would like to. I write a lot because that’s what I do when I can't be in the studio – all my works, both the two- and three-dimensional ones, arise through writing. When I return to London, sometimes I don't leave my studio for days. That, most likely, can't be called a balance – it's more like one big conglomeration.