Life cannot thrive in a monoculture – it needs diversity

An interview with Ann Mirjam Vaikla and Saskia Lillepuu, the curators of the international group exhibition “Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention” at Narva Art Residency

Narva Art Residency's annual exhibition “Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention”, currently on view at the historical Kreenholm district in Narva, brings together artworks by 17 artists. The exhibition pays attention to the entanglements of human lives with other-than-human beings, rhythms, and worlds. At a time when cycles of production and consumption amplify the environmental trouble pulsating throughout the planet, the exhibition searches for possibilities to sense our shared vulnerability and interconnectedness, and turns to the the entanglements of life and death in times of ecological distress.

Kreenholm district, built in the 19th century on the shore of the waterfall on the Narva River, was once home to the largest textile mill in Europe. In 1913 over ten thousand people worked there, and the compact complex of industrial architecture included a factory, a hospital, workers' barracks, directors' houses, and Kreenholm Park. The factory's hospital (1913) is considered an architectural treasure and is still the city's main hospital.

The exhibition includes several commissioned artworks created by Hans Rosenström (Ghost in the Room), Marit Mihklepp (Mineral everybodies), Juss Heinsalu (standby replacement redundancy), and Sepideh Ardalani & Sandra Kosorotova (garden for death). The works have been developed during physical and virtual residencies and multiple site visits to Narva Art Residency (NART). The exhibition catalogue includes commissioned essays by curator and writer Tanel Rander (The Itch) and by the ambassador for climate and energy policy Kaja Tael (Life in a transition era), in addition to essays by the project’s curators: Saskia Lillepuu (Inheriting habits, inhabiting stories), Ann Mirjam Vaikla (Third Curator), Piibe Kolka (You’re running. Everyone’s got holes) and Kerttu Juhkam (Igniting Conversations).

Arterritory presents the following short conversation with the curators of the exhibition, Ann Mirjam Vaikla and Saskia Lillepuu.

What are the main lessons you learned about being human and our relationships with the non-human world while working on this exhibition?

Ann Mirjam Vaikla: The main lesson, struggle and understanding throughout the exhibition process has been how to not leave the human out, or behind. It is easy to imagine a world and its continuity without a human who, for some reason, tends to lean towards destruction of itself, its surroundings, as well as towards other beings. But how can we keep on going forward while returning to the indigenous way of seeing humans as part of the ecological diversity we are living in, and not at the top of the hierarchy?

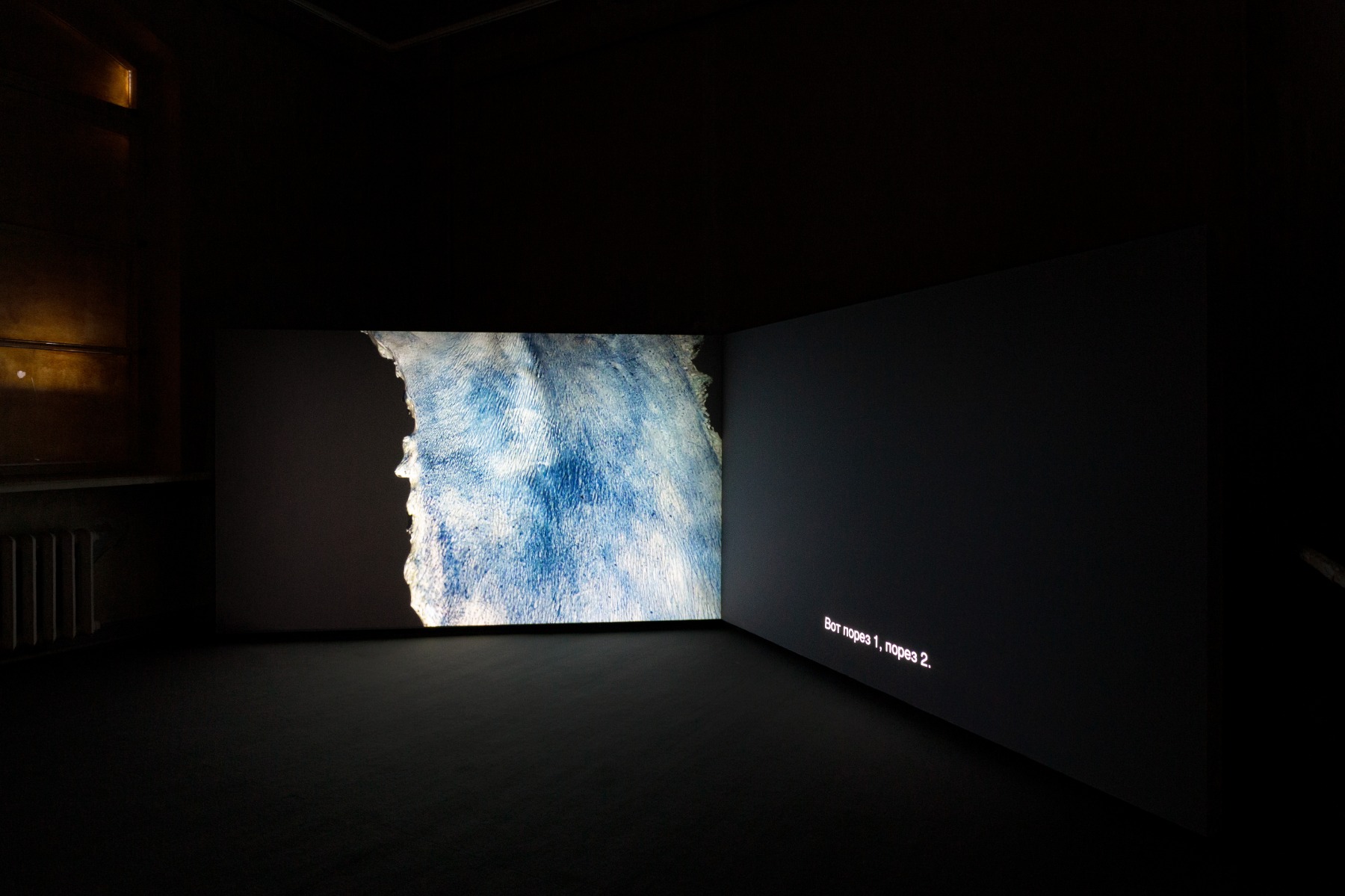

Pia Arke. Arctic Hysteria, 1996 / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

How long did you work on this exhibition, and why did you feel that you could not not make it?

Ann Mirjam Vaikla: I received the first letter from Saskia around two years ago in 2019. In spring we met in Narva to observe the space in the light of the initial exhibition proposal. Half a year later, I stepped in as a co-curator and started to engage with the process creatively by reflecting on possible artist selections and proposing new ones from my side. We aimed to have an exhibition that would open in autumn 2020, but exactly one year ago, in the middle of lockdown and all the anxiety caused by that situation, we took the bold decision to postpone the opening by half a year. This was an excellent decision – in the midst of uncertainty, we received the opportunity to slow down and engage with the complexity of the subject matter much more than we ever dreamed we could. There is a quality in artistic processes that can only be achieved by prolonging the period of creation. I feel grateful to be able to address the theme of ecological distress both before and during the coronavirus outbreak – it feels more topical than ever before.

Melanie Bonajo. Night Soil – Nocturnal Gardening, 2016 / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

The title of the exhibition is “Point of no Return. Attunement of Attention.” Do you agree that we, as a civilisation, have reached the critical point of our human evolution and are now facing the risk of extinction? Could this crisis serve as a lesson in humility, or it is just an illusion, and we as a civilisation have entered the unstoppable process of self-devastation?

Saskia Lillepuu: I don’t think the human species will face actual extinction anytime soon. The problem is that many other species and ecosystems have disappeared and are disappearing because of our ubiquitous way of life that runs on fossil fuels and is driven by profit. Certainly, we are also hurting ourselves, humans, but I think what is more problematic is the fact that we are making life on earth less diverse, and as a consequence, the planet has become less hospitable for many other creatures. Life cannot thrive in a monoculture – it needs diversity. “Point of no Return” refers to the fact that a lot of the damage done to the planet is irreversible even if we change our ways now, and that’s not because it’s too late but because nature doesn’t work like that – there is no pristine state we can restore; we don’t have that ability. Human societies will inevitably affect their environment, but we can do less harm than we are doing now if we start to take into consideration others besides just humans.

Flora Reznik. Change in Y, Change in X, 2019 / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

The concept of the exhibition states: “Narva Art Residency’s annual exhibition for 2021, Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention, turns to the entanglements of life and death in times of ecological distress.” If we look back at art history, death is consciously or unconsciously always present in art. Could we say that artists are kind of like mediators who, through their work, remind us about death and provoke us to think about it from different and essential perspectives?

Ann Mirjam Vaikla: The possibility to engage with death has been taken away from most societies in the West. It is institutionalised, sterilised and turned into a taboo we tend to be afraid of. The artwork garden for death by Sepideh Ardalani and Sandra Kosorotova, situated at the vacant Kreenholm textile manufacturing territory, has its starting point in the dead, the rotten, the “ugly”… A ton of food scraps, soil and horse manure have been distributed at one of the historical entrances of the former manufacturing site. “Only death can create space for something new to flourish”, Ardalani said during one of the discussions. “This work has been brought into being to support the contingent flow of life, to exist on the terms of its inhabitants and not of those of its gardener nor to satisfy a human desire.” (Ann Mirjam Vaikla, Third Curator. Exhibition catalogue of Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention, 2021, p. 4).

Juss Heinsalu. standby replacement redundancy, 2021 / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

In some way, the Kreenholm district embodies our obsession with the idea of progress and it's consequences. How do you imagine the future of the Kreenholm district, and what role art could play in shaping it?

Ann Mirjam Vaikla: I think the new life at Kreenholm can flourish the fullest through its inhabitants. Who are the new users of the space? How to support these new inhabitants who have ideas, plans and contacts, but are often lacking (financial) support? We have quite a number of examples, both in Estonia and all over the world, of renovated, slick spaces that stand empty due to top-down planning – it produces an incapability to sync with the visions and rhythms of artists and creative minds. One of the main thoughts I propose in my essay in the exhibition catalogue has been borrowed from Gaston Bachelard’s description of the motto of the mollusc: “One must live to build one´s house, and not build one´s house to live in.”* I have found this quote relevant when leading and building up the Narva Art Residency over the past years.

Saara-Maria Kariranta. For the Memory of Upcoming Generations II, 2017/2021 / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

How do you view the role of the artist in times like these? What can an artist do that no one else does? Why is it important to take an active position?

Saskia Lillepuu: In the context of the man-made ecological crisis that we are living in, I think we need to reevaluate our attitudes and relationships to nature. That might sound “soft”, but I mean in it in a very real and practical way – relationships are formed in actions. The question is how we actually treat and impact nature by living in certain kinds of societies as individuals, species, communities, cities, businesses, nations, and so on. It’s a large-scale, complicated shift in habits and principles that I hope for.

Alma Heikkilä (left), Felipe de Ávila Franco (right) / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

When we think of art and social change, I’m very sceptical of claims that artists possess some sort of special insight into society or that art can change the world. I prefer to think of art like music or literature – making and listening to music, as well as reading and writing literature, can generate very personal yet collective changes and motions in us as thinking and feeling beings. They affect us and bring our attention and our presence into something deeply. This exhibition, for example, hopes to bring the visitor’s attention to the interconnectedness of life that our human lives depend on.

Hannah Mevis. welcome in the bubble _ enter at own risk, 2019, visitor: Piibe Kolka / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

How strong nowadays do you feel is the voice of art and the power of art?

Saskia Lillepuu: I think there is still a lot of mysticism around art that the art world maintains by retelling certain grand narratives, like the artist as genius. I truly think it does a disservice to art and artists. It alienates the public from art and creates the sense that in order to understand it, you need a degree. And I think that’s why the voice and power of art nowadays is not very strong – we are not encouraged to engage with art as a creative tool with which we can sense and make sense of the world around us. Artists train their senses and artistic skills and fine-tune creative thinking and ways of expressing. That’s their expertise, but anyone can train those skills. I think we would benefit if we had more creative sensorial training in schools because we are emotional, feeling creatures, but we often grow up without knowing how to live with our emotions and desires. It would also make professional art more accessible to more people.

Hannah Mevis. welcome in the bubble _ enter at own risk, 2019 / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

Is there any possibility to build a new human, a new thinking, a new philosophy on top of this on-going gigantic wastebasket which is the world we’re inhabiting right now?

Saskia Lillepuu: There’s always the possibility to learn and the potential for change. But I think we are a bit obsessed with novelty and ‘the new’. Very little that we come up with is radically new, even if it so packaged. I hope we don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater, but also that we start paying attention to what the bathwater does to the environment where we dump it.

Anne Noble. The Bee Wing Photograms / Bruissement 1–8, 2017 / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

What the pandemic has brought home to people is that we can’t go back to the way things were. In the meantime, we don’t have very clear alternative solutions about how to move on. The key word of our time is “uncertainty”. What kind of culture could stem out of this notion of uncertainty?

Saskia Lillepuu: Living in the world has always been uncertain, but we don’t like to think about it too much because it’s scary. We strive for safety – it’s how we are wired as biological creatures. If there is a lack of safety, we become anxious and we develop psychological and health problems. If you consider how many people are living with anxiety nowadays, then it becomes quite obvious that the uncertainty was not created by the pandemic; the pandemic simply made it more palpable to those who didn’t feel it before. But safety and uncertainty are not opposites, luckily. Some developmental psychologists I have read argue that kids that grow up to be wholesome people don’t grow up in an illusion that the world is safe, but they do have a steady support structure – they know they are not alone. And that’s what is lacking in our societies – steady support structures. So, acknowledging uncertainty could help us create more supportive, attentive and caring communities and cultures. But that kind of change takes time, dedication, patience, and the willingness to make mistakes and learn.

Alma Heikkilä. Found living in total darkness, 2020 - on the left / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

Could you mention three works of art included in the exhibition that have the potential to change the perspective of a viewer or otherwise leave a strong and memorable mark? Ones that really embody the power of art in it's essence.

Ann Mirjam Vaikla: This is a very difficult question, as each of the 17 artists offers a voice on its own and in relation with the others in a complex dramaturgy that unfolds at the former residence building of Kreenholm’s director. I would probably say something different tomorrow, but today I see myself entering the most southern exhibition hall containing the large-scale, double-sided work found living in total darkness (2020) by Alma Heikkilä, which becomes a screen absorbing the sunlight from the window behind it. The light captured in-between the two canvases exposes a universe of other-than-human organisms making the visitor aware of the multiple scales and their entanglements with each other – both in- and outside of our own bodies. Behind it there is an old TV on the floor showing the video Arctic Hysteria by the artist Pia Arke (1958-2007). Arke, known for her criticism of the projected exoticism, eroticism and savageness that white culture projected on Greenland’s people and landscapes, exposes her nude body while tearing apart an image from her childhood home in Greenland that she is crawling over. I turn my head and look at the north end of the exhibition hall. I see the painting Wanderer by Estonian artist Manfred Dubov. This work brings to the surface our inner world’s connectedness with the environment. Once we demolish our surroundings, we tear up our psyche.

*G. Bachelard, The Poetics of Space. New York: Penguin, 2014, p. 126

Nina Schuiki. brace brace brace, 2018 / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Narva Art Residency (Joala 18), Narva, Estonia. Through June 20

Participating artists: Saara-Maria Kariranta, Hans Rosenström, Marit Mihklepp, Felipe de Ávila Franco, Alma Heikkilä, Hannah Mevis, Pia Arke, Juss Heinsalu, Manfred Dubov, Flora Reznik, Sissel Marie Tonn, Melanie Bonajo, Anne Noble, Nina Schuiki, Vera Anttila, Sepideh Ardalani, Sandra Kosorotova

Title image: Marit Mihklepp. Mineral Everybodies, 2021 / Point of No Return. Attunement of Attention. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo