Being at a rave is a clearly defined moment in time

An interview with Kati Ilves, curator of the “Up All Night: Looking Closely at Rave Culture” exhibition at Kumu Art Museum

Maria Helen Känd*

Curator Kati Ilves, who works at Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn, focuses on key topics in contemporary society – such as the relationship between technology and humans, popular culture, and the networked world – and the integration points of the natural sciences and art. Her major projects in recent years include curating, for example, Katja Novitskova’s solo exhibition at the 57th Venice Biennale in the Estonian Pavilion, as well as the joint exhibition by Estonian rap-performer Tommy Cash and fashion designer Rick Owens.

On May 3 her new exhibition, “Up All Night: Looking Closely at Rave Culture”, which views the rave as a political-poetical phenomenon and also looks at its intersections with social processes, opened at the Contemporary Art Gallery of Kumu Art Museum.

Why make the audience look back at the 1980s and 1990s – what can we draw today from the factory parties and open-air raves that took place back then?

For me, the rave is not an end in itself, i.e., it’s not just a party. People do go there to do things they would normally do at a party, but raves also actually reflect what is happening in society. The rave culture that began in Britain in the late 1980s has been viewed by theorists such as Simon Reynolds as a response to the Thatcher regime. The economy then suddenly became service-oriented, with industry drying up. Thatcher emphasized the credo that community does not exist – it is individualism that counts. Given the rigid nature of class society in Britain throughout the ages, the raves offered a sense of social coherence that society lacked.

It seemed to me that about five years ago, rave culture picked up again. I saw a similar phenomenon then, but I didn’t exactly know what it was. If society is well organized and cohesive, then there is less of a need for an alternative party culture. In terms of human rights and liberal values, the trends of recent years in Estonia are worrying, but the more something is suppressed, the more something different starts to balance it elsewhere.

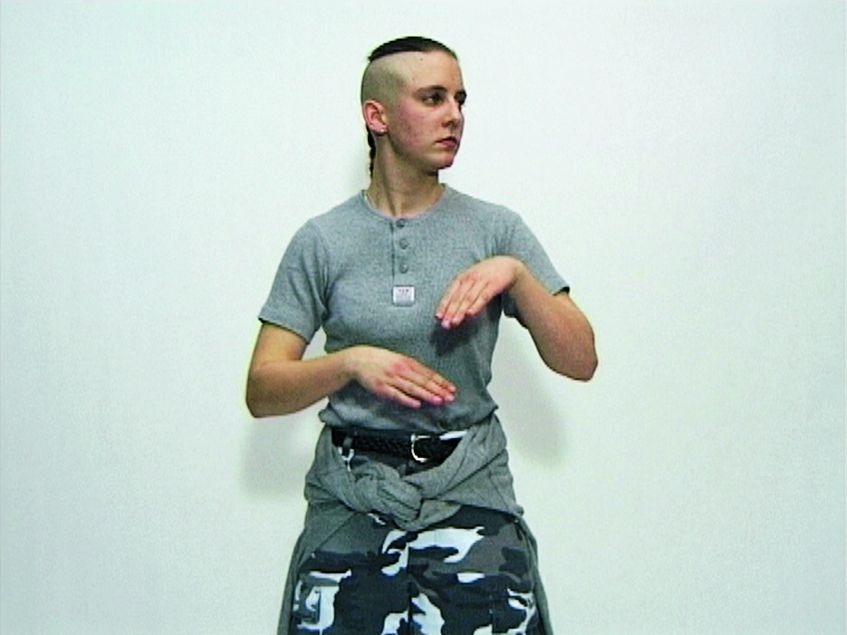

The Buzz Club, Liverpool, UK / Mystery World, Zaandam, NL. 1996–1997. Still from video

How did the idea for this exhibition come to you? Was it initiated by a specific work of art, an exhibition, or a special nightlife experience?

The rave, as a phenomenon, has always fascinated me, especially as a powerful physical-experiential phenomenon that also affects visual culture. I have been working on the topic of sound art at Kumu for a long time, looking for common ground between visual art and other disciplines. However, the signs of the reactivation of rave culture, as well as the works created on this topic, began to reveal themselves to me at one point and it became clear that this topic is in the air.

Rineke Dijkstra’s “The Buzz Club” was the first work of which I knew that the show would eventually be created. I saw it at her solo exhibition in 2017 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. A year earlier, at the Berlin Biennale, I had seen Anne de Vries’ works inspired by hardstyle, which fascinated me because Vries made the connection between raving and high technology impressively clear.

In fact, I wanted to do this exhibition back in 2019, but at that time it changed slots with another exhibition – a project by Tommy Cash and Rick Owens. The second attempt was to come in 2020, but it got cancelled due to the pandemic. This is the third time.

The Buzz Club, Liverpool, UK / Mystery World, Zaandam, NL. 1996–1997. Still from video / Courtesy of the artist

Looking back now, are you happy that the current exhibition opened now, when people are craving for contact?

Yes, I’ve been thinking about that. And also about the kind of program an institution is supposed to organise when, at the same time, people are dying in hospitals and the medical system is in crisis. As a result, we have canceled some web events because they may seem inappropriate.

Another parallel emerged: in Britain, raves were able to function well for some time before they were banned in 1994 and thus pushed underground. Last summer I started to hear from acquaintances in Berlin, foremost, that everyone is going to forest parties – the information about them is exchanged on WhatsApp, and the police have come to break up the gatherings. It seemed that due to the pandemic, the circle was complete: once again, the culture of raving had become illegal.

I have heard that this exhibition also evokes nostalgia, but that was not the goal for me. For some time there had been a feeling that maybe rave culture belongs to museums. That’s why the timing is accurate.

Hydra Decapita. 2010. Still from video / Courtesy of the artists

This is the first nightlife-themed exhibition in Estonia. Why do you think it took that long to arrive? Was the rave culture still too intense in the nineties and 2000s, and so we needed time for us to reflect on it properly?

When a lot of things happen at the same time and all your energy goes toward work and execution, you can't really think much about why something is being done. Later, an understanding arises that, “yes, this was it”. I imagine that people from these times may not see rave culture as I put it together in the exhibition. But such situations are common.

The video works in the exhibition depict underground nightlife aesthetically and poetically… although many probably don’t see the beauty in intoxicated people and moving sweaty bodies. What do raves and poetry have in common?

I think there is a huge potential for freedom in both.

Of the art forms, poetry is perhaps the most unrestricted – it allows you to be who you are. A proper rave has the same effect. This experience is completely unique – it’s individual, but its poetic nature lies in the fact that it’s a collective experience of loneliness.

This reminds me of a police spokesman’s comment about a party at Atlantis [a club in Tartu] from around 2004. I’m paraphrasing here: “On Saturday, there was a drug raid in the nightclub Atlantis, where eight drunk individuals were identified. None of them resisted the police because the stimulant ecstasy makes people friendly.”

It’s so incredibly beautiful that the question arises – then what is the problem? [Laughs]

I have had better and worse nightlife experiences. In the old days, for example, when you went to the city on the weekend in Tallinn, there were a lot of crowds and British boys, but at the good raves people would be at their best. Of course, this is largely due to the substances that evoke temporary feelings of euphoria and love, but there is something in this experience that society, in its everyday functioning, often does not offer. Being at a rave is a clearly defined moment in time, a short-lived utopia – a beautiful moment that you should not let pass by!

Hydra Decapita. 2010. Still from video / Courtesy of the artists

How are contemporary art and club culture related – apart from the facts that they have the potential for social resistance and they both bring subcultures together?

The parties nowadays have become very visual. In the late eighties this trend did not dominate, but video technology has developed enormously. Today, visuality is an elementary part of any party, and it doesn’t have to present itself electronically or digitally. Many recent electronic music festivals focus on installation, sculpture, and creating an environment.

Looking back, it seems that the nineties were a terribly exciting time in Estonia – this becomes evident even in Tarvo Hanno Varres’ photo series. A lot of new things happened at once in fashion, in art, and in nightlife. People were bold and experimental, and it was perfectly okay to do a fashion show at a nightclub during a party. Over time this playfulness has disappeared, but now it’s starting to come back, although this may just be my wishful thinking. It makes me glad to see art in the context of a party, even if it sometimes functions as decor. You can find everything in the category of “party visuality”, and the picture is pluralistic. I think it’s fruitful.

Hydra Decapita. 2010. Still from video / Courtesy of the artists

The exhibition approaches the rave as a social activity that resists authority, and is based mainly on the club culture in Great Britain as well as in Ukraine. What kind of similar connections between civil unrest and nightlife can be found in Estonia’s recent history?

I guess there are no such concrete examples from here. The Ukrainian revolution, the so-called Euromaidan, took place relatively recently, in 2014. In 1991 there were not many photo and video recording possibilities in Estonia, and thus not much was documented as compared to 2014, when pictures and videos were taken by smartphones.

Now, on the other hand, we are much closer to social unrest: fortunately, the marriage referendum and the abortion debate have receded, but we were quite close to a crisis of democracy.

The curatorial text promises that the exhibition introduces the arrival of rave culture in Estonia and the subculture that emerged from it. In the exhibition, however, we see works by only three local artists – Kiwa, Tarvo Hanno Varres, and Sandra Kosorotova. How are these rather complex processes presented in the exhibition?

There will be more elaboration on the formation of rave culture in Estonia in the booklet accompanying the exhibition. There are basically no works from that time from local artists that deal specifically with this topic. We had a series of portraits by Tarvo Hanno Varres in the museum collection, and it seemed logical that it should be part of the exhibition because the photographs portray the era. It’s significant because he photographed, for example, the DJ and stylist Heivi Saaremets, as well as Elena Natale, the current director of the [techno] club HALL, who back then probably no one imagined would now be managing this Berghain-like club in Tallinn.

Kiwa started playing records and making art at the same time. We considered several variants, but finally decided that he should make a new work that expresses the nature of a rave, one in which sound is translated into light. It functions as a comment on being alone in a certain spatial constellation.

I invited Sandra Kosorotova because it seemed that one of the niches that should be touched upon is Lasnamäe’s[1] trance scene, which is perhaps even more political and attitudinal. We had different ideas on the table, and finally she came up with a mind map made on textile that explores the connections between Lasnamäe’s nightlife and spiritualism. We were fascinated to find out that many of the party animals of that time had become Hare Krishnas.

Mark Leckey. Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999 / Video still from DVD / Copyright Mark Leckey / Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

To what extent do these spiritual searches exist in modern rave culture? Is entertainment what is actually pursued, and the pursuit then euphemistically expressed with new age spirituality concepts?

I would like this concept of spirituality to be really just a decoration in rave culture. What makes it strange in the context of partying is that the people with whom I myself have attended the same events are now, for example, against vaccinations or masks. Perhaps some also believe that the Earth is flat. In the past, these were not topics to be discussed at all.

When it comes to the entertainment aspect, I would have focused on it more in the pre-corona times. The pandemic has created a very strange backdrop to everything. The accusation of the entertainment industry has, of course, been made to rave culture, and it’s broadly competent because large party venues and festivals have become well-earning enterprises. At the same time, artists and DJs today have high expectations for technical solutions, and this also sets expectations for the organizers. In addition to a refined party experience, this do-it-yourself-for-your-friends format certainly lives on.

Mark Leckey. Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999 / Video still from DVD / Copyright Mark Leckey / Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

During the period of lockdown, club culture in Tallinn has largely been left out of the support schemes – as if nightlife is not a necessary cultural phenomenon. In this context, it is interesting that Kumu – an important state institution – will have a rave exhibition. Do you feel that rave culture can and should be rehabilitated, so that it is not viewed as a matter of concern only for the peripheries of society?

I personally believe in rave culture and the power of this movement. It would be wonderful if the exhibition rehabilitated it. Kumu is a large institution; it represents values that the Estonian state has also promised to stand up for. If rave culture had no value, I would not be showing it.

The exhibition is, of course, a separate medium; it has its own agency and inner life that cannot compete with the party itself. Perhaps this is precisely why the exhibition could have a rehabilitative force, so that we can make a strong statement that confirms the necessity of this phenomenon.

Mark Leckey. Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999 / Video still from DVD / Copyright Mark Leckey / Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

From 2006 to 2010, Kumu ÖÖ (Kumu NIGHT) parties were held in the museum. The exhibition by Tommy Cash and Rick Owens was also accompanied by a one-time night event – Kumu RAVE. Are there any events planned in the current exhibitions program?

There is hope that a rave will take place at the end of the exhibition period. We have it scheduled, but do not dare to announce it until the situation allows!

*Maria Helen Känd is a freelance curator and cultural critic, and a master's student at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

[1] Lasnamäe is the most populous administrative district of Tallinn, the capital of Estonia. The district’s population is about 119,000, the majority of which is Russian-speaking. Local housing is mostly represented by 5- to 16-story-high panel blocks of flats built in the 1970–1990s. Lasnamäe is usually referred to as a Russian ghetto.