A Bit of Homegrown Metaphysics

A two-part solo exhibition by the Latvian artist Roman Korovin (‘Lives and Deaths’ and ‘My Family Photo Album’) is on view at the Helsinki Hippolyte gallery through 29 August 2021.

Roman Korovin’s exhibition at the Hippolyte gallery is comprised of two separate parts, each presented in a separate room. The ‘Lives and Deaths’ series shown in the main hall of the gallery uses a somewhat absurdist approach to the existential subject of life and death and their cyclic processes. One of the principal storylines focuses on a man named Kaspars, who, having committed a suicide, finds himself ‘on the other side’. It turns out, however, that ‘the other side’ is not so different from this one after all: a tiny bit more magical, perhaps, but otherwise, by and large, exactly the same. The rest of Korovin’s characters ‒ Zane, Zinaida, Olga and Pekka ‒ are going about their normal business, dealing with things like backache, stolen and found cars, raking dry leaves in the autumn and collecting birch sap in the spring: their lives and deaths revolve around the most ordinary things and events.

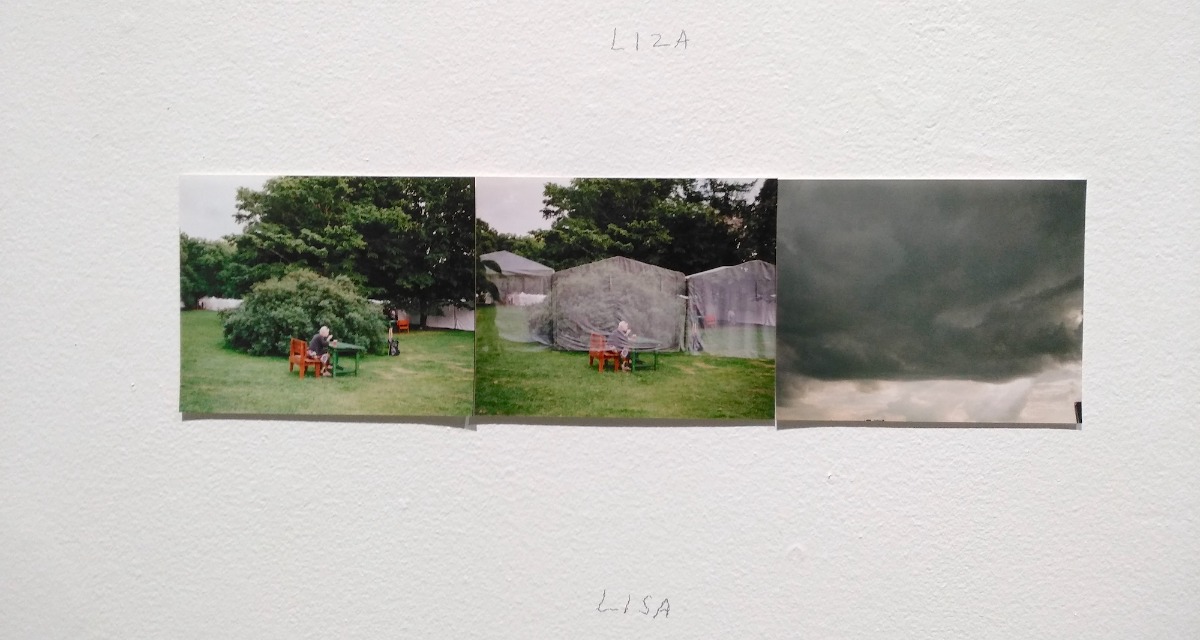

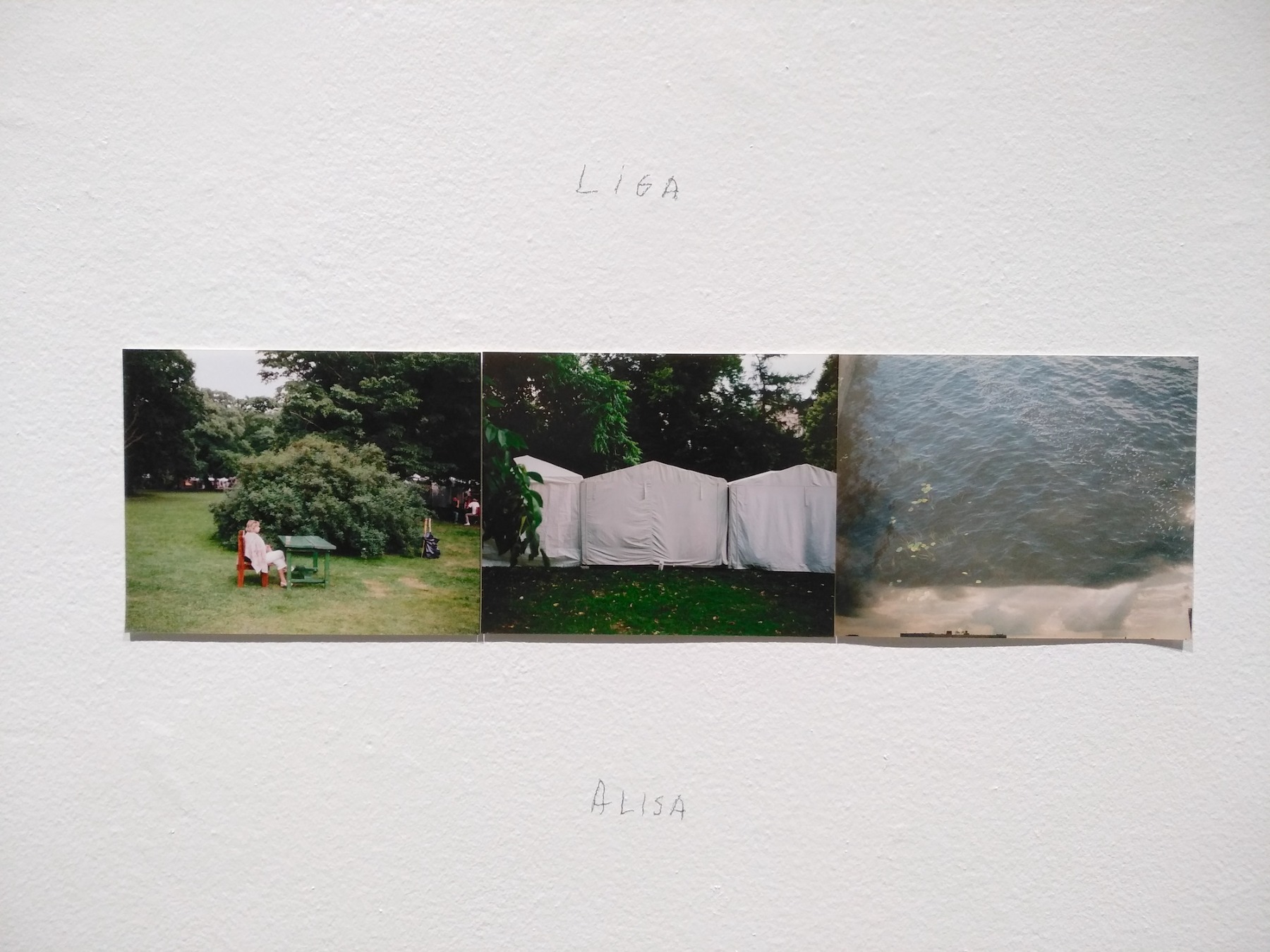

The second part, entitled ‘My Family Photo Album’, is a collection of photographs reminding us of pictures from ordinary family archives, capturing significant and precious moments over the course of a lifetime. For a child, the prenatal world, life and afterlife existence are not separate phenomena but parts of a single journey, all of them worthy of an album entry. Moreover, a pillow can be the child in this photo album, a lamp pole ‒ the father, a cardboard box can serve as a car and snow lumps amidst the shrubs ‒ visiting distant relatives.

Photos: Roman Korovin

According to the press release for the exhibition, ‘Photography as a medium plays a crucial role in Roman Korovin’s exhibition at Hippolyte. His works ask us to, for a moment, put aside the usual way of reading photography as a narrative tool. He uses the medium’s ability to shift between the real and the constructed to create fictional worlds and enables them to be perceived as real. With these works, Korovin’s exhibition suggests that the world around us is indeed magical, and the things we imagine may as well be real.’

We contacted Roman a day before the opening to learn more about the show on view in the Finnish capital through August 29.

Could you tell us about the gallery itself ‒ what kind of pace is it?

The Hippolyte art gallery was recommended to me by the Latvian artist Inga Meldere who is based in Helsinki.It is the oldest art gallery in Helsinki focusing exclusively on photography. It is located in the city centre, housed in a historical cinema building. A nice large space with two galleries: one of the rooms, the Studio, is smaller, the other one, the Main Gallery, used to be an auditorium with an actual screen ‒ and there is still a somewhat theatrical, dramatic feel to it. It has balconies and a high ceiling, and all of it prompts a sort of architectural vision.

Did you come up with the subject of Lives and Deaths, quite dramatic and theatrical in its own way, before you had heard about the gallery?

All of my recent works and exhibitions dealt with the subject of people and their respective contrast or blending with the world around them as manifested in objects, geometric shapes or signs. They were all a kind of montage. As for ‘Lives and Deaths’, it is a title that sets the bar really high ‒ and is totally abstract at that. I have always found it a very beneficial thing for your art ‒ thinking about matters that are unattainable and not completely comprehensible.

The Main Gallery imposes an architectural-temple aesthetics; it actually really presents itself as a kind of shrine ‒ with columns in the shape of large photographs, with depictions of life stories, with objects as relics. A non-confessional shrine. Except the life stories here are not the deeds of saints but of ordinary people who live around us.

Indeed, your works have actual protagonists who even have names.

Over the past five years, names have featured increasingly often in my pieces. At the previous Survival Kit, I simply showed people’s names and some signs. And yet I do not talk about these people through their portraits. The narrative here is driven by the landscape: the human being is merely a small dot on it. That’s a bit of homegrown metaphysics made up of everything that surrounds me.

The second part of the show is a more chamber-style one. Entitled ‘My Family Photo Album’, it is a series of pictures of a boy who is telling his story from the moment of birth until the death of his dad. Family photos. Except the boy is actually represented here by a kind of white bag, a little roll-like pillow. People make these kinds of pillows out of fabric in winter and tuck them in the gap between the windowpanes ‒ to stop the cold air coming in. So that’s what my character and his family are like: the bigger roll is Mum and the smaller one is the actual boy. His dad at some point dies in a car crash and flies off to Heaven.

So there is this subject of life after death?

It’s all very simple indeed ‒ everything is in the form of a family album. This is where I am born, this is me at the age of one, this is me under the Christmas tree. And since Dad is killed in a car crash, this is a photo of his soul among other souls up there in Heaven. It is a cosmically unreal thing presented in the format of ‘happy families’.

There is also a film and various objects like honey jars, candles, some kind of paintings.

Do you generally find it important to speak about not just about life in this world but also some kind of afterlife?

The main subject of both projects is the idea that we do not simply exist in an ordinary space but that we are subject to a great variety of forces and things. There are millions of different levels of existence all around us. And I find it interesting to explore it this way, in a detached and quite abstract manner. Phantasmagoria, I believe that’s the word. Yes, there is some kind of cosmic-phantasmagorical element to the whole thing.