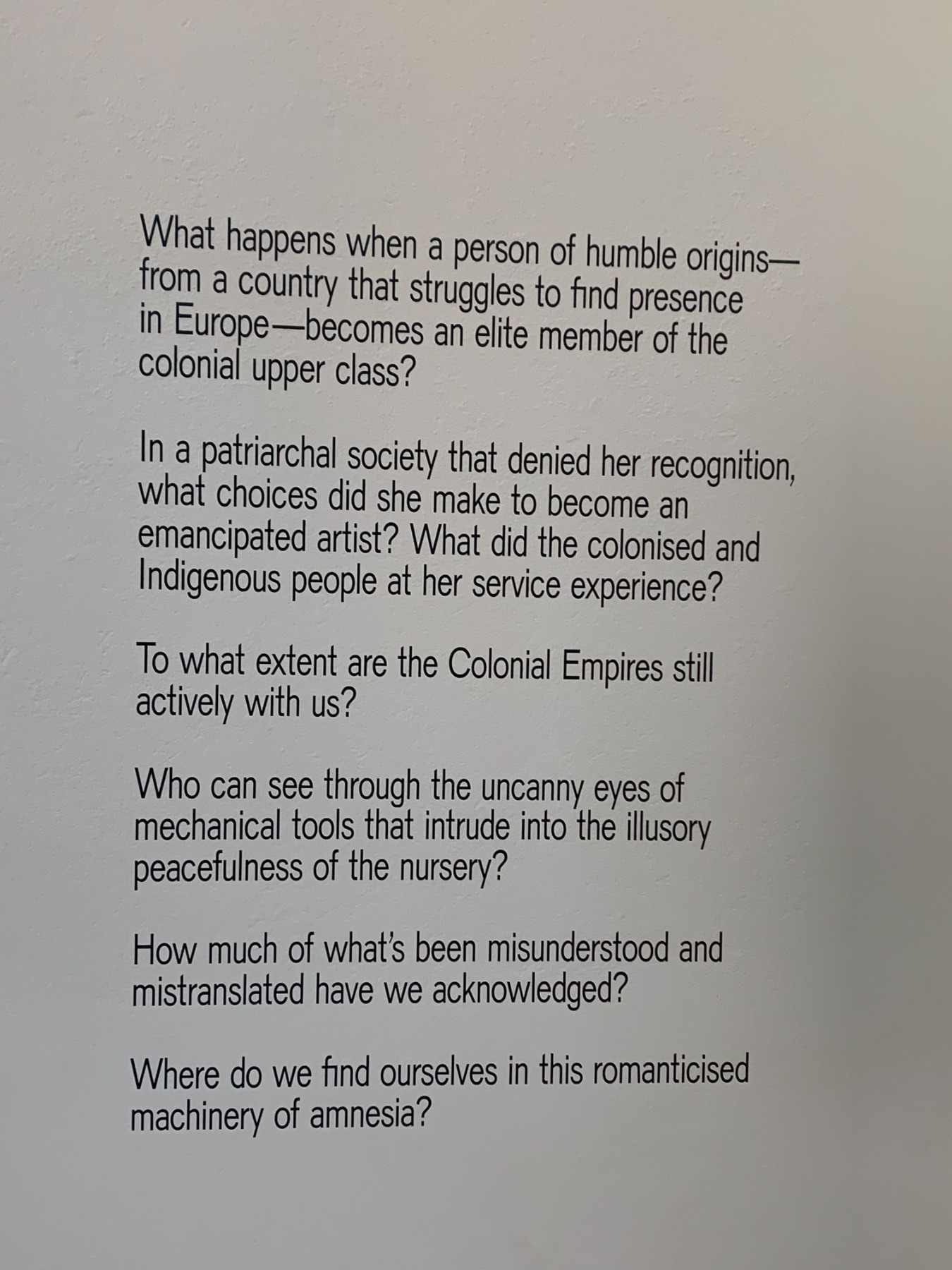

A report of change and upheaval

The 59th Venice Biennale

After a three-year break, the Venice Biennale – the oldest and still most prestigious art fair in history – is back. One of the two pillars of its structure are the national pavilions which, it stands to reason, represent national art – a categorisation that for at least a decade has sparked debate about its relevance to the times as well as the logic of attempts to draw territorial boundaries in art.

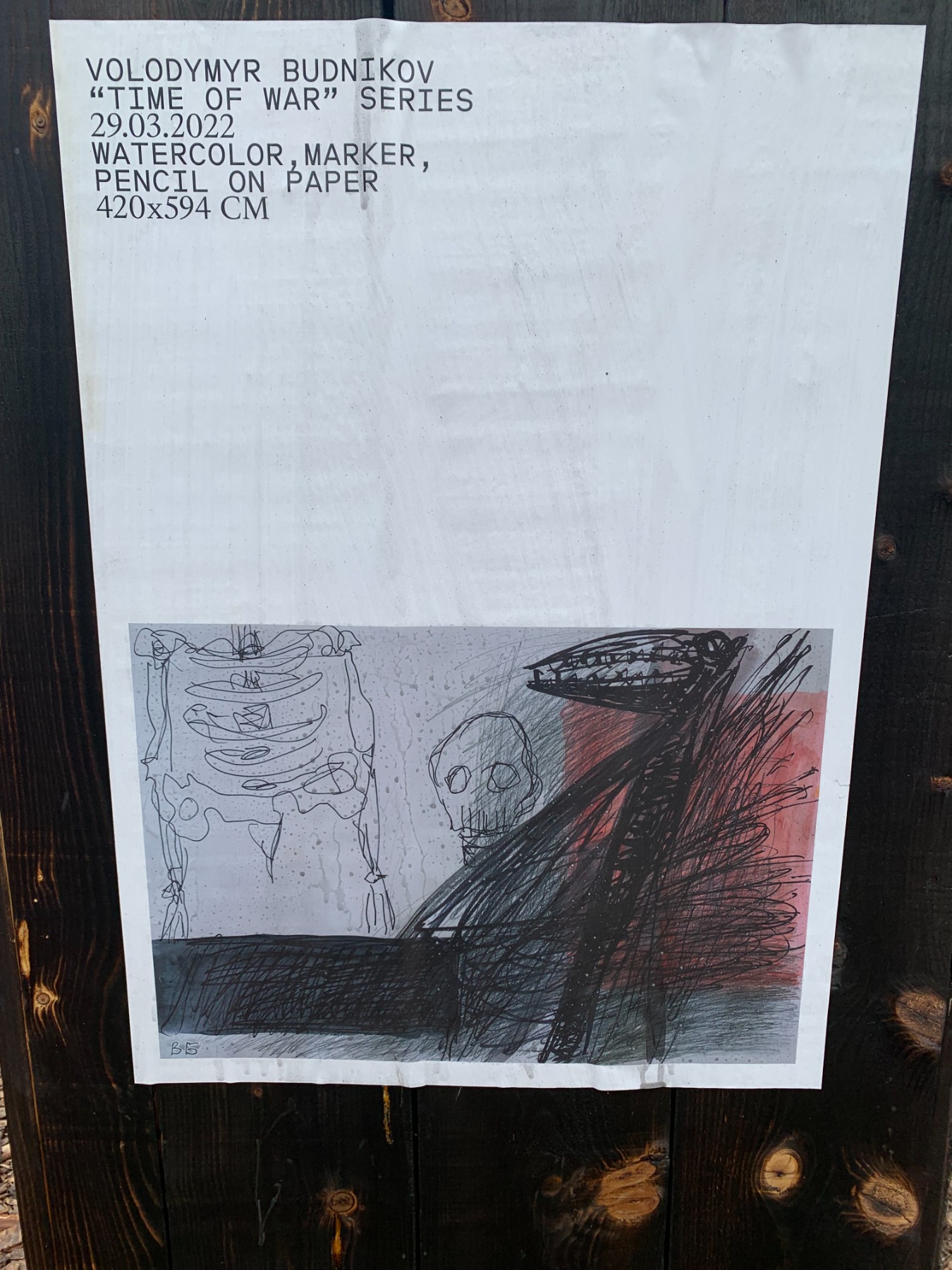

In the current geopolitical situation, this issue has only been exacerbated. The pavilion of the Russian Federation, built in the notable year of 1914 in one of the two central venues of the Biennale, the Giardini, remains empty this year after both the curator, Lithuanian Robert Malasaukas, and the two featured artists, Alexandra Sukhareva and Kirill Savchenkov, refused to participate in the Biennale in protest against the Russian invasion of Ukraine. During the opening days of the Biennale, there appears to be a more-than-usual presence of the peace-keeping Caribinieri in the vicinity of the empty Russian Pavilion (but perhaps this is just my imagination, fueled by the times we find ourselves in). And just a few hundred metres away, in the heart of the Giardini, the last-minute Piazza Ucraina has been created, an initiative of the curators of the Ukrainian Pavilion, Borys Filonenko, Lizaveta German and Maria Lanko. Densely covered with mulch (wood shavings), charred/burnt wooden constructions set up between benches display posters by various Ukrainian artists; a huge pyramid of sandbags rises in the middle. It is a clear recreation of what we’ve been seeing on the nightly news over the last two months – scenes of Ukrainians trying to protect their cultural and architectural monuments with sandbags.

Piazza Ucraina - an initiative of the curators of the Ukrainian Pavilion, Borys Filonenko, Lizaveta German and Maria Lanko

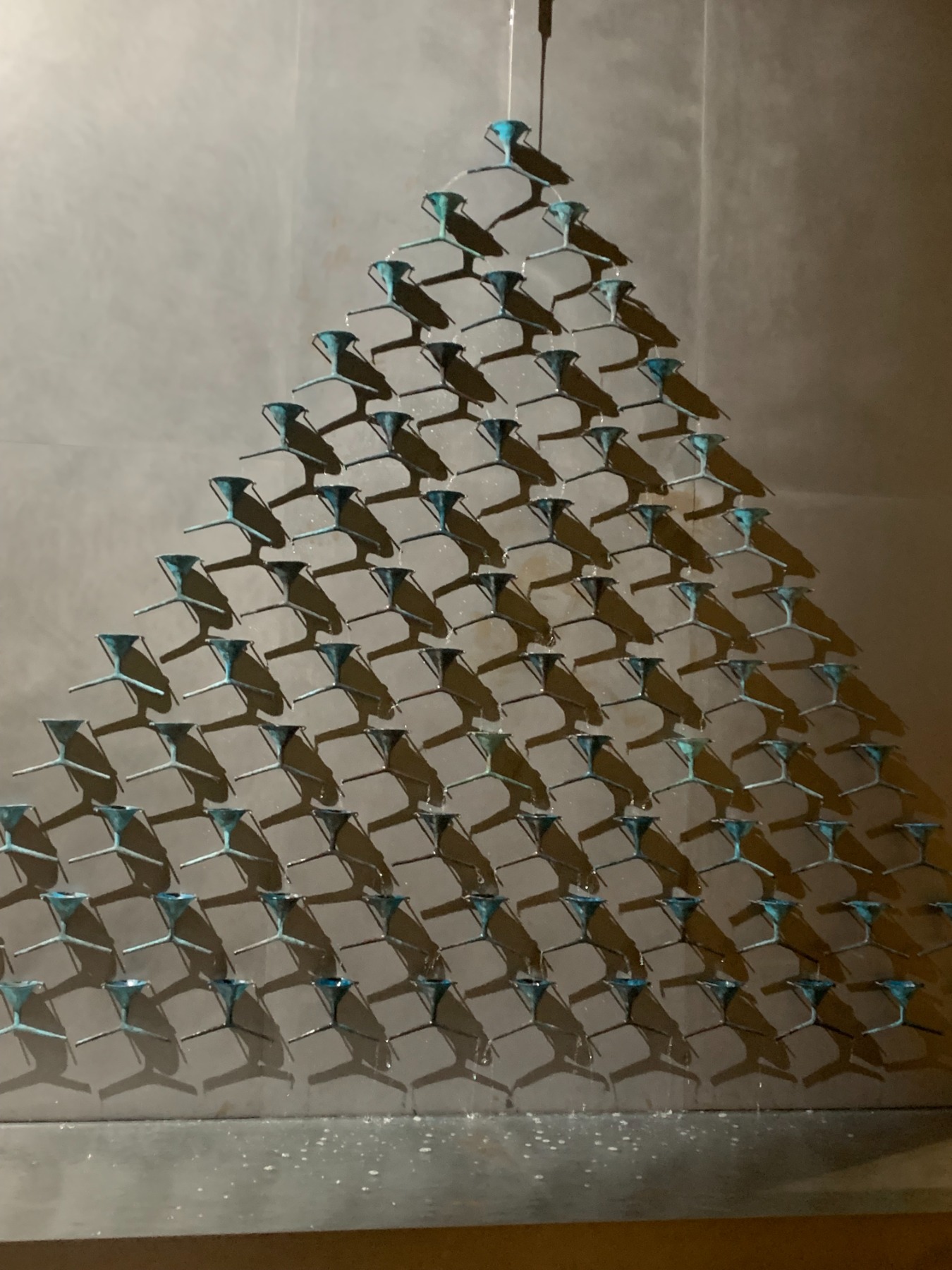

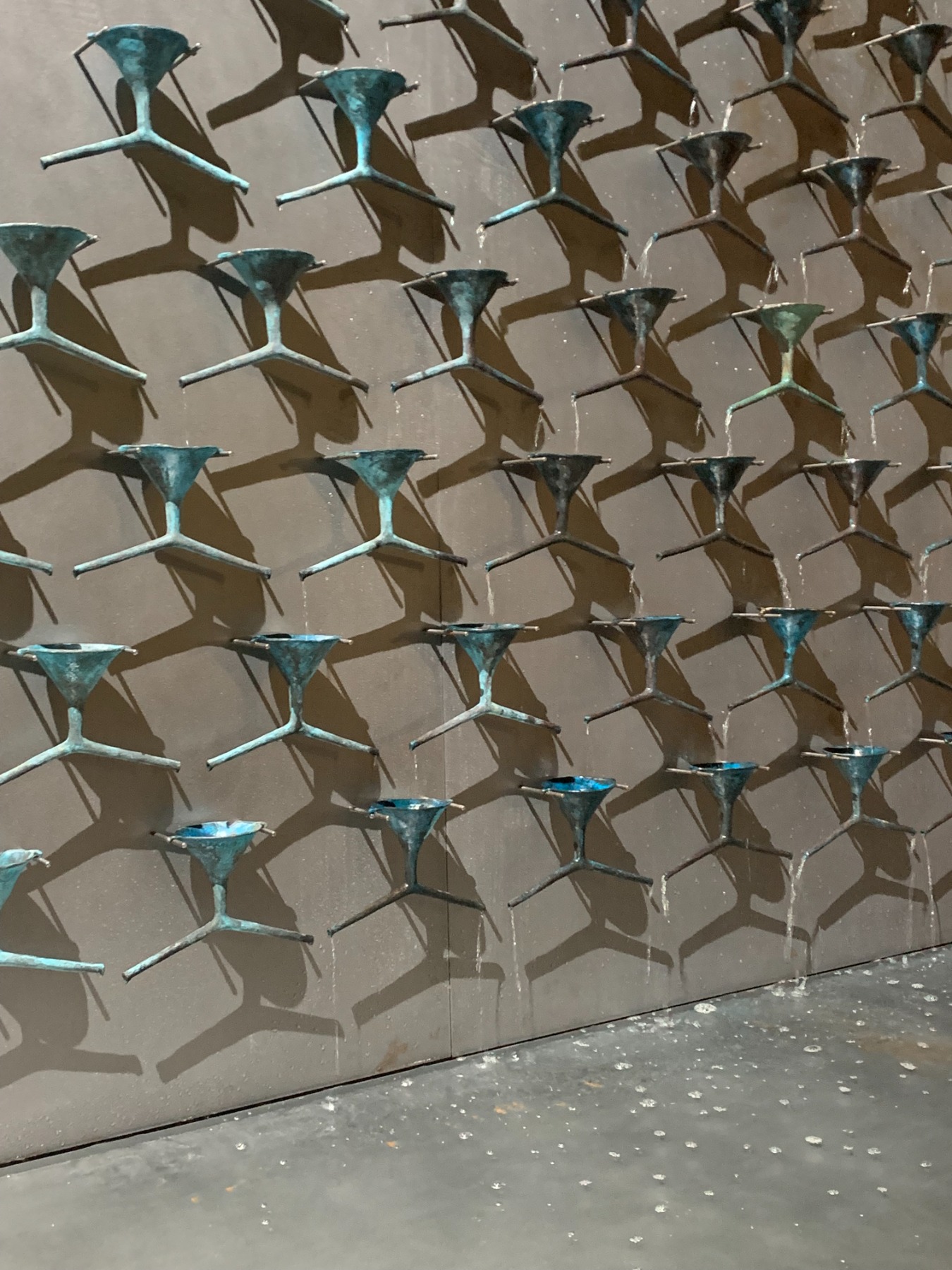

Despite the war, the Ukrainian Pavilion located in the Arsenale features the installation The Fountain of Exhaustion. Acqua Alta by Russian-Ukrainian artist Pavlo Markov. The installation’s presence here was made possible thanks to the solidarity of many art institutions and people.

"The Fountain of Exhaustion. Acqua Alta" - installation by Russian-Ukrainian artist Pavlo Markov

On the whole, however, the war in Europe is not visible in the background of Venice – only the sighting of a yellow jumper with a blue pin at the opening of the Hungarian Pavilion and the Ukrainian flag hanging next to the flag of Latvia at the Latvian Pavilion in the Arsenale serve as reminders. However, the imprint of the pandemic and the existentialism it has stirred up are still there – in the huge crowds on the opening days experiencing the joy of physical encounters (with people and with art), in the national pavilions, and in the exhibition The Milk of Dreams by Cecilia Alemani, Head Curator of the 59th Venice Art Exhibition. And more present here than ever before is the revelation of the self not being the centre of the universe but rather just a piece of cosmic dust, a concept that used to be left unspoken and was preferably swept under the bed. Also present is the physicality, the materiality of art itself – unlike many previous exhibitions, Alemani’s Milk of Dreams is very “tangible” – there is relatively little new technology here, and no video works. Sculpture, installations and tapestries dominate – things usually associated with the word “craft”.

Katharina Fritsch. Elephant.

The Milk of Dreams is introduced in both venues by large-scale sculptures created by women (80% of the 213 featured artists are women or gender non-conforming) – the hyper-realistic Elephant by German artist Katharina Fritsch in the Central Pavilion at the Giardini, and the massive bronze sculpture Brick House (a female torso) by American Simone Leigh at the Arsenale.

Simone Leigh. Brick House.

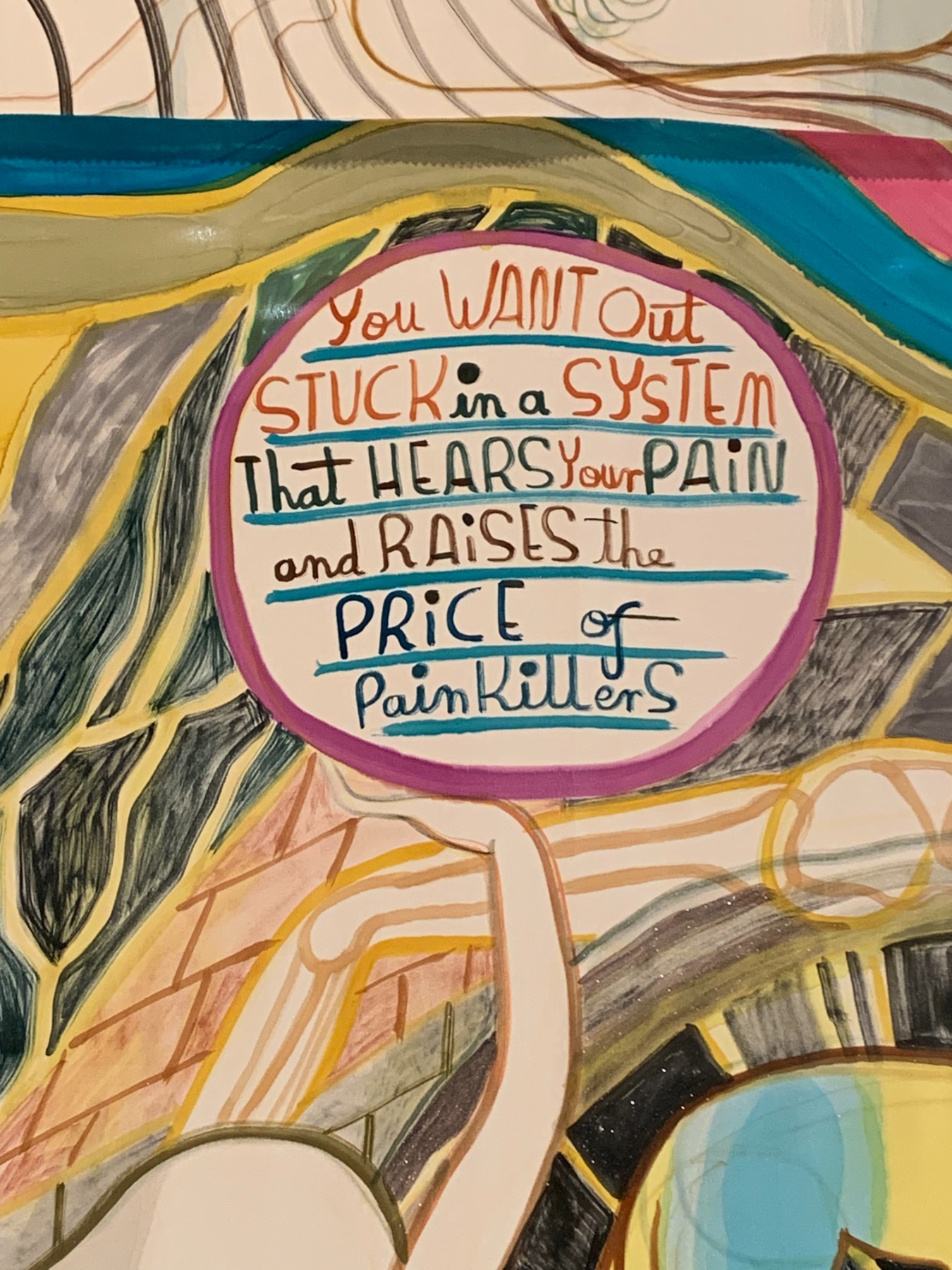

This year Fritsch is also one of the recipients of the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, which will be awarded on April 23. The other recipient is artist and poet Cecilia Vicuña, who has dedicated her life to translating the works of Chilean and Latin American poets (thus preventing them from being lost) as well as to the fight for the rights of Latin America’s indigenous peoples. This Biennial is like a seismometer graph, a record of the changes and shocks of the past years that have changed, and are still changing, the world. Both the US and the UK are represented by black artists – the aforementioned Simone Leigh (US) and Sonia Boyce (UK), respectively; France’s featured artist this year is the Paris-born, London-based Algerian photographer and videographer Zineb Sedira; the Nordic Pavilion has been temporarily renamed the Sámi Pavilion (Pauliina Feodoroff, Máret Ánne Sara, and Anders Sunna); the Polish Pavilion features an exhibition by Roma artist and activist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas; while this year the Estonian Pavilion has been placed in what is the usual spot of the Netherlands Pavilion in the Giardini while the latter country exhibits its works elsewhere in the urban environment of Venice.

Giulia Cenci. Dead dance.

This Venice Biennale is a testimony to the fact that, most likely, things will never be “the way they used to be”. As a close friend of mine said: “Everything that native peoples have been saying for centuries has been translated here into an artistic language that the West understands.” When you walk out of the Arsenale along the long walkway adjacent to the building, you have to pass under Giulia Cenci’s surreal installation dead dance. Surrealism is yet another concept that is very present at this Biennale.

Exhibition The Milk of Dreams by Cecilia Alemani, Head Curator of the 59th Venice Art Exhibition

Gabriel Chaile. Exhibition view

Kapwani Kiwanga. Sunset Horizon.

Kapwani Kiwanga. Sunset Horizon.

Emma Talbot. Where do we come from. What are we. Where are we going.

Emma Talbot. Where do we come from. What are we. Where are we going. Fragments

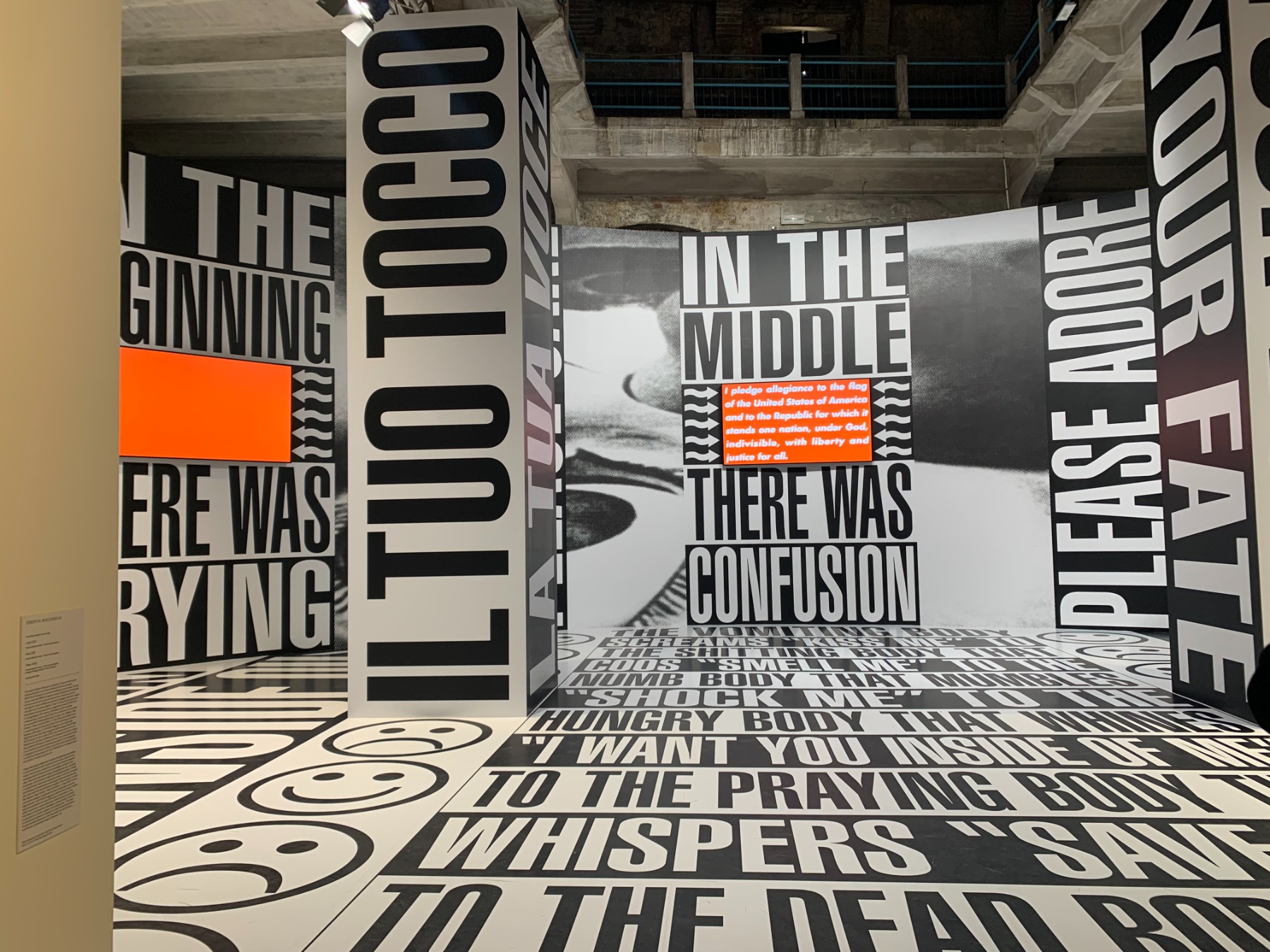

Barbara Kruger. Untitled.

Exhibition view. Seduction of the Cyborg.

Ekspozīcijas skats. Seduction of the Cyborg.

Marguerite Humeau. Migrations.

Marguerite Humeau. Migrations.

Niki de Saint Phalle. Gwendolyn.

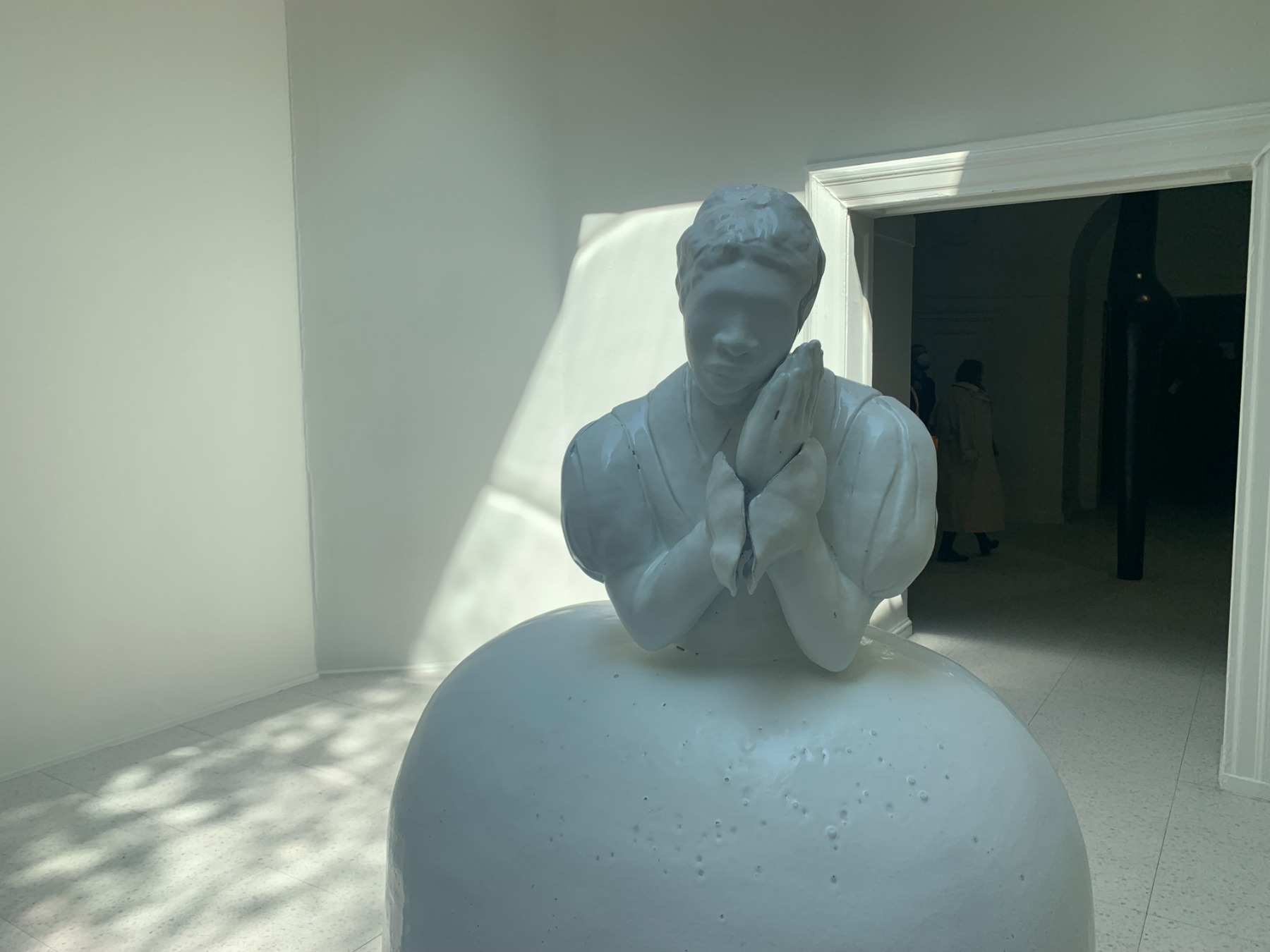

Pinaree Sanpitak. Painting series.

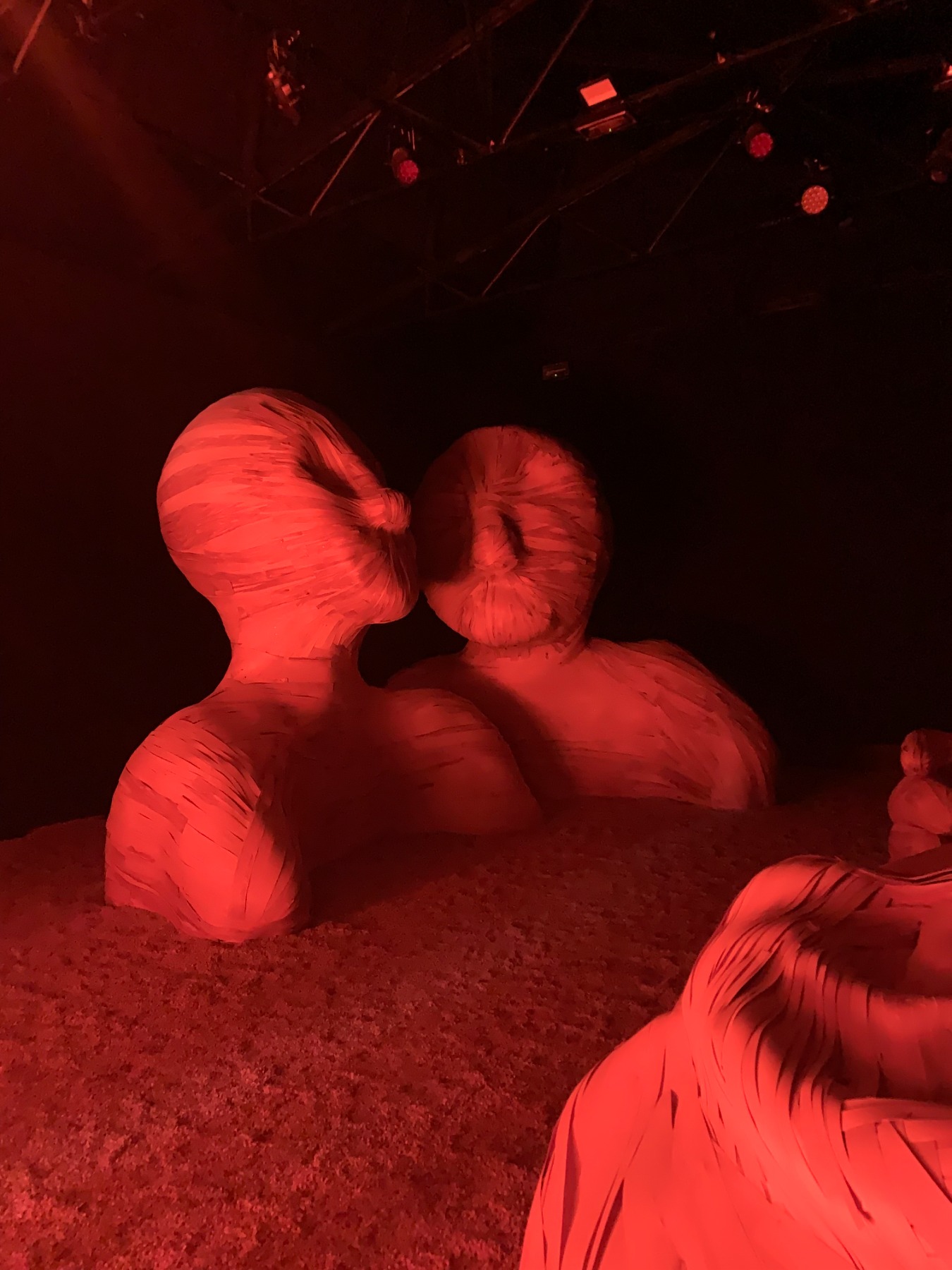

Precious Okoyomon. To See the Earth Before the End of the World.

Precious Okoyomon. To See the Earth Before the End of the World.

Tau Lewis. Sol Niger (With my fire, I may destroy everything, by my breath, sould are lifted from putrified earth)

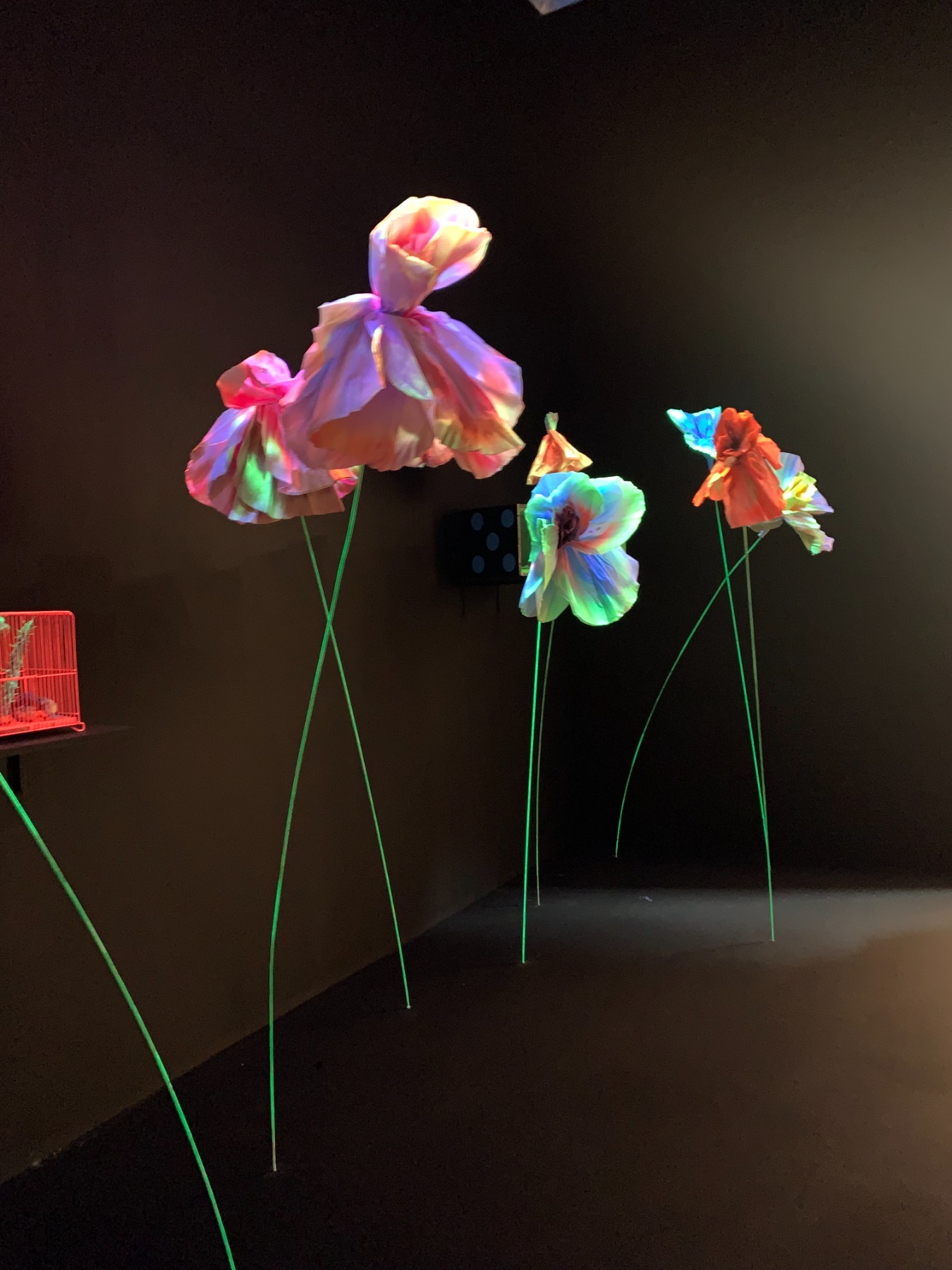

Tetsumi Kudo. Flowers.

The National Pavilions

French Pavilion: artist Zineb Sedira,

curators: Yasmina Reggad and artReoriented (Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath)

Sámi Pavilion (Nordic Pavilion): artists: Pauliina Feodoroff, Máret Ánne Sara, and Anders Sunna,

co-curator: Katya García-Antón

Spain Pavilion: artist Ignasi Aballí,

curator: Ignasi Aballí

Swiss Pavilion: artist Latifa Echakhch,

curator: Francesco Stocchi

United States of America Pavilion: artist Simone Leigh,

curators: Jill Medvedow and Eva Respini

Estonian Pavilion (placed in the usual spot of the Netherlands Pavilion): artists Kristina Norman un Bita Razavi,

based on the life and works of Emilie Rosalie Saal

British Pavilion: artist Sonia Boyce

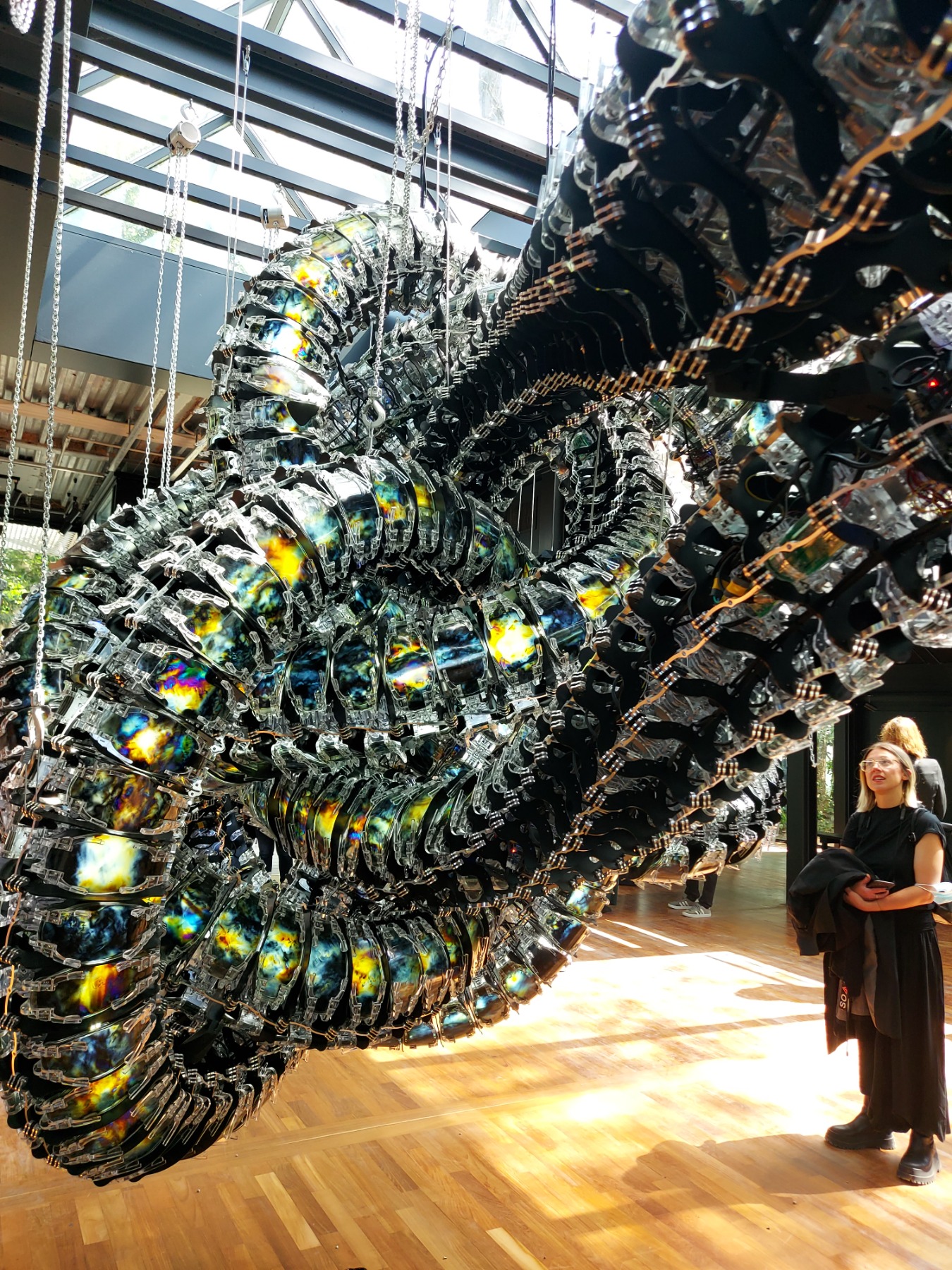

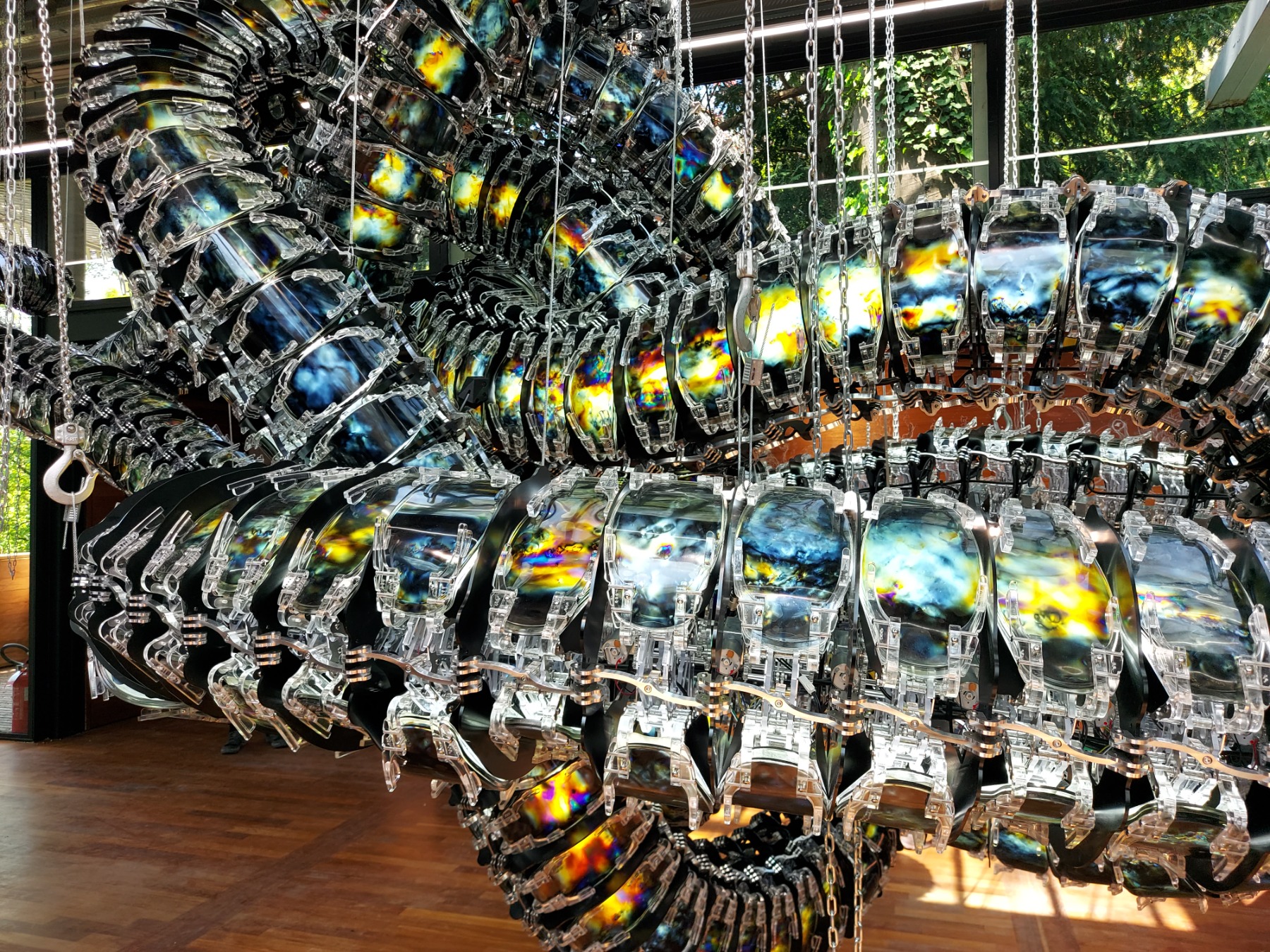

Korean Pavilion: artist Yunchul Kim,

curator Youngchul Lee

Austrian Pavilion: artists Jakob Lena Knebl and Ashley Hans Scheirl,

curator Karola Krau

Lithuanian Pavilion: artist Roberts Narkuss,

curator: Neringa Bumblienė

Latvian Pavilion: artist duo Skuja Braden

curators: Solvita Krese, Andra Silapētere

Polish Pavilion: artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas,

curators Wojciech Szymański and Joanna Warsza