Pavel Otdelnov on his exhibition Acting Out

A brief interview with the Russian artist, who is exhibiting in London

The first UK solo exhibition by Russian artist Pavel Otdelnov is being held at the London cultural centre Pushkin House from 13 October 2022 until 28 January 2023. The works presented in Acting Out have been created specifically for Pushkin House’s historic premises in Bloomsbury, and present the artist’s critical commentary on the humanitarian catastrophe associated with the war in Ukraine. Otdelnov’s paintings are an attempt to reveal the mechanisms and sentiments that have led to the war and which are still ongoing today. The artist created his exhibition in the UK as a participant of the Global Talent programme, developed by Arts Council England and supported by Pushkin House.

Pavel Otdelnov. Bunker. 2022. acrylic on canvas. 67.5x67.5

We’ve written about Pavel’s projects several times, including an extensive interview last year with the artist about his exhibition Ringing Trace, dedicated to the history and consequences of the Soviet nuclear project in the Southern Urals. Now we have spoken with the artist once more, to learn about his new exhibition and where it is taking place.

What does Pushkin House mean to you, as an organisation founded in the midst of the Cold War in 1954 by a community of Russian emigres and British Russianists? What do you think about the institution and its history, and how does it feel to exhibit in this space?

Pushkin House has a long history as an independent space for intercultural dialogue. I’d say that it is a unique place which brings together people who study Russian language, are interested in Russian history and culture, and at the same time do not answer to the Russian authorities. It’s a place where independent expression and dialogue are possible. Here they have a very rich programme of events, including presentations of new books written about modern Russia and discussions and meetings with historians. The first English person I met here is writing his thesis about Serafim Sarovsky and the depiction of this figure in history and in Silver Age literature. It’s clear that many people, despite the current horrifying circumstances, continue to have an interest in Russian history and to study the Russian language.

The house itself is not exactly an exhibition space. It is an 18th-century building with columns, fireplaces, preserved features, a grand piano and a narrow staircase. It was a real challenge for me to come up with an exhibition for such a space, as it was practically impossible to change anything in the building and there was hardly any money for setting up the exhibition – this was no easy task.

Pavel Otdelnov. Grey Suits. 2022. acrylic on canvas. 110x150. Detail

Is there a general idea behind the exhibition Acting Out? How do you define the name of the exhibition itself?

We started thinking about my exhibition in June 2021. I conceived it as a continuation of Ringing Trace that approached the topic of the Cold War. Initially, it was supposed to be an exhibition about preserving the traces of the Cold War and about certain important episodes of this period. I thought out the entire exhibition and drew some sketches in the middle of February 2022 – it felt like I’d come up with a brilliant idea. But after the current war started, it no longer seemed appropriate to create an exhibition about the Cold War. So, I reconceptualised the exhibition as a reflection on how Russia ended up in this catastrophe, how what is happening right now became possible. I took the name of the exhibition from the language of psychotherapy; ‘acting out’ means a hysterical transition into a state of aggression. At the same time, it implies resentment and a desire to replay and change the past.

The exhibition starts with a pompous flying carpet that leads nowhere, and a symbolic descent into the bunker. The exhibition is made up of three parts flowing one into the other: “Ressentiment”; “Generation”; and “The Beautiful Afar” – you climb the stairs from the first to the last section.

There are two works dedicated to the putsch – an attempt at conservative counter-revolution of 1991 which is still happening in the present day. I conceived the painting “Grey Suits” even before I started working on the exhibition, when I watched the meeting of the Security Council on 21 February 2022. I thought of the work “Swan Lake” even earlier – here, instead of ballerinas, are OMON [riot police] forming a human chain. I dedicated an entire section to my compatriots – those who have left the country, and those who return as “Cargo 200” [code word for the transport of military fatalities]. There is also a compositional rondo, where the time machine from “Guest from the Future” [a Soviet TV series] and the nuclear briefcase have a keen resemblance. Here, the future turns out to be the past, and nostalgia turns out to be poisonous and extremely dangerous. I see the actions of my country’s leaders as a hysterical attempt to stop a future which they don’t understand – a future in which there is no place for them – at any cost.

Pavel Otdelnov. Parade. 2022. mixed media. 210x260

Your exhibition is an attempt to examine the current state of Russian society. Some of the works are almost poster-like. How have your artistic optics changed in recent times? Has making a “direct statement” become more important for you?

Yes, making a direct statement has become more important and more urgent. The public position of an artist is now even more important than their artistic talent – in some ways, the position itself has become a mark of artistic quality. Maybe my most recent works are more poster-like, however art remains a space of reflection for me. At first glance it can be untimely and even inappropriate - but I did not choose these circumstances and I consider it my duty to speak about them. I’m also speaking as a citizen of a country which I didn’t choose. I think it is very important to recognise the catastrophe that is occurring around us, and understand what has made it possible.

People have got used to looking at tragic events of the past from the “bright side”, from the point of view of who is right. They often forget that history is written by the victors – and this is a huge mistake. Aside from the fact that the authorities appropriate and instrumentalise past victories to justify current actions, there is also another serious problem. Practically nowhere in literature nor cinema do we see a depiction of genocide or war crimes carried out in the name of people who are just following orders, in the name of normal people who are just quietly living in the aggressor country. These people tell themselves that they are “not interested in politics”, that they “don’t know the whole story”, and that those who run the country of course know better. In our school history and literature lessons we never learnt/spoke about the banality of evil – betrayal isn’t just joining the “enemy” side, but is found in everyday submission and conformism. People can find a million ways to justify themselves. Aside from Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones, I can’t think of a work that explores this idea so deeply. It is uncomfortable to look at this and unbearable to think about, and it is much easier instead to think of ourselves in the right and to dehumanise the “other”. The logic of dehumanisation only works in one direction, and propaganda is built on this. And that’s why in the cultural sphere so little has been done to vaccinate people against this way of thinking. Acceptance of personal responsibility is an agonising process that comes at an enormous cost. This is why I believe that my voice is important.

Pavel Otdelnov. Generation. 2022. mixed media. 210x260

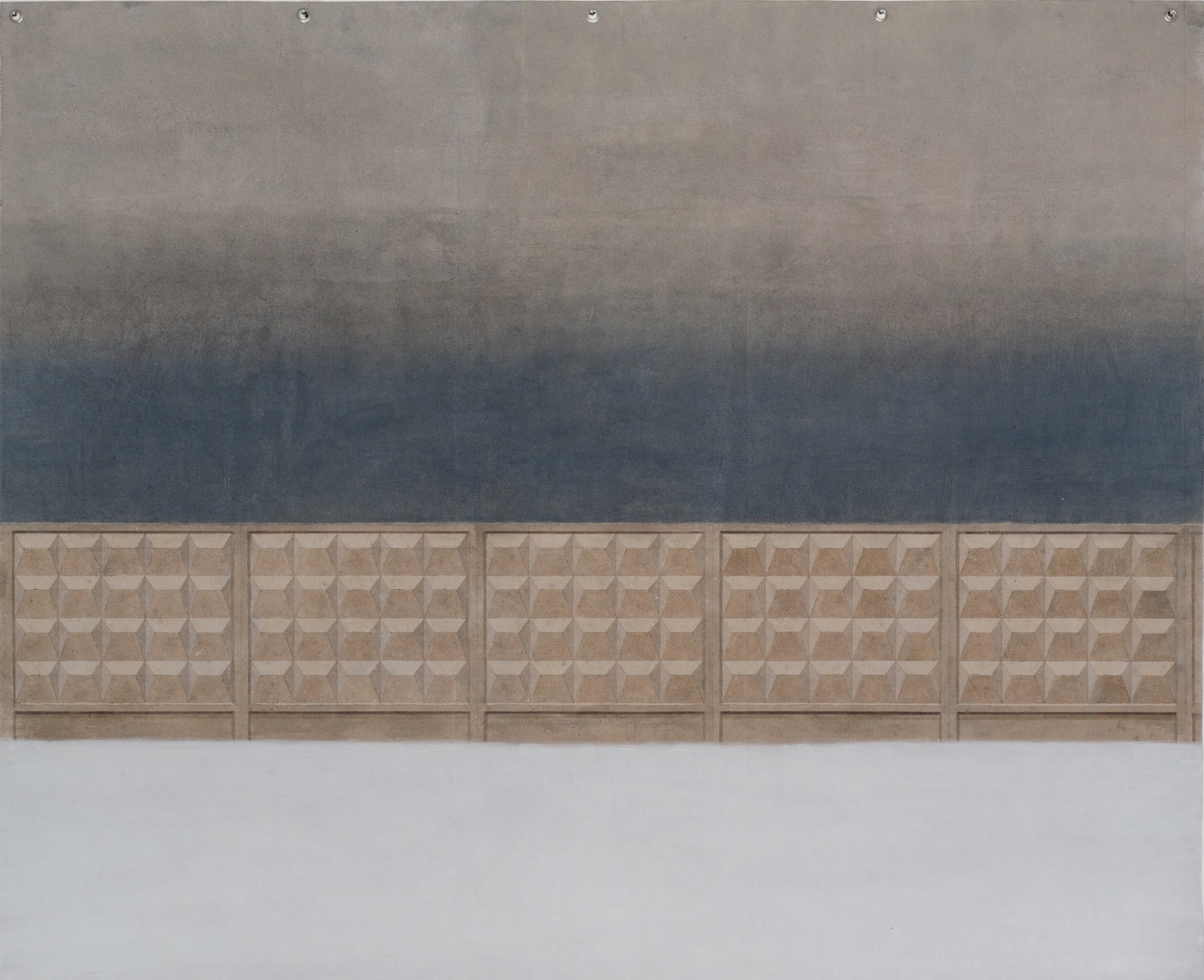

Pavel Otdelnov. The Wall. 2022. mixed media. 210x260

You are one of the artists who has openly criticised the war in/Russian aggression in Ukraine since the very beginning. But even now, it seems that people like you are the minority. There’s no open support for the war, but there’s no noticeable opposition either. Why do you think this is?

I think that opposition from inside the Russian cultural sphere is not visible for several simple reasons. I won’t mention censorship and the new laws, which can sentence dissenters to an interminable sentence in a Russian prison – this is well understood. Recently, new measures were discussed which would prohibit state-run exhibition halls from showing artists who have expressed an anti-war position. Artists who have remained in the country have almost gone underground – showing their works in apartment exhibitions or in lesser-known spaces. Such exhibitions with anti-war statements take place without wide publicity because, understandably, no-one is writing about this – if just to protect their publications as well as the artists, their families and the exhibition spaces. Making any kind of anti-war statement from inside the country is a hugely brave gesture. But even such a gesture, that requires desperate bravery from an artist living in Russia, comes across to an overseas audience as negligible and weak. What’s more, making any public statement will most likely raise a multitude of ethical questions – take, for example, the recent controversy over Andrey Andreev’s inscriptions on the walls in St Petersburg.

Obviously, even inside the country, open support for the war seems obscene – even those who do support it don’t share their views, to avoid the hatred of the people around them – the vast majority of whom are against the war.

Exhibition views / Pavel Otdelnov "Acting Out" at the London cultural centre Pushkin House

Pavel Otdelnov. Tsar Bomba. 2022. oil on canvas. 67.5x67.5

Pavel Otdelnov. Money. 2022. mixed media. 210x260

Pavel Otdelnov. Swan Lake. 2022. acrylic on mdf. 32x40

Pavel Otdelnov. Seats. 2022. oil pastel on canvas. 60x80

Pavel Otdelnov. Time machine. 2022. acrylic on canvas. 40x50

Translated from Russian to English by Rachel South

Title image: Pavel Otdelnov. Cargo 200. 2022. mixed media. 120x150