The Hidden Side of Ülo Sooster

Freudian couch conversation between exhibition Sooster 100: View from Private Collections curators Liisa Kaljula and Elnara Taidre

There are artists who just don’t fit into the terms of one movement or “-ism”, one medium or one national art history. All that refers to Ülo Sooster (1924–1970), one of the key figures in Estonian art of the second half of the 20th century, but also in the Moscow underground of the 1950s and 1960s. With his unique creative fecundity and imagination, Sooster can be named a pioneer of surrealism, abstractionism as well as some other lines of the post-II World War modernism – and, moreover, a precursor of conceptual and postmodernist thinking, whose innovative searches and discoveries can be traced in painting and graphic art, book illustration and animation. Until the 4th of May, in the Mikkel Museum in Tallinn an exhibition Sooster 100: View from Private Collections is on display, where one can get acquainted with the main topics in Sooster’s painting and drawing via selection of artworks mostly from non-museum collections – part of which are renown classics of his heritage, while another part are new findings being introduced to professional circulation. As mapping out the exhibition materials as well as their research was quite a challenge, curators of the exhibition Liisa Kaljula and Elnara Taidre decided to open the project via format of mutual interview, where reference to Freudian-like therapy session – a couch conversation – suits well with one of significant sources of Sooster’s surrealism.

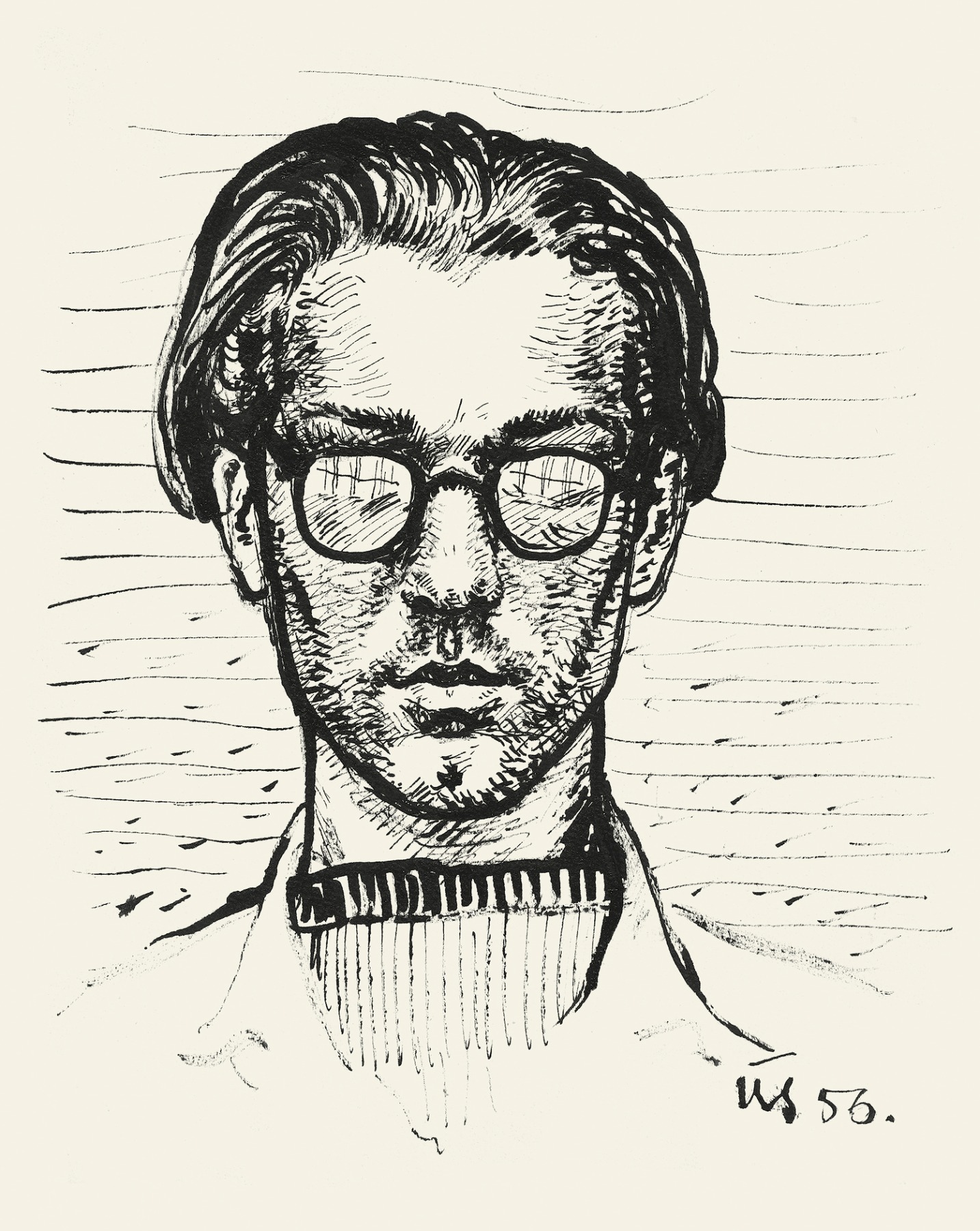

Ülo Sooster (1924–1970). Self-Portrait with Glasses (1924–1970). 1956. Indian ink. Sooster family collection

Elnara Taidre: If you had to open the phenomenon of Ülo Sooster with a couple of sentences to a person, who knows nothing about his biography as well as the context of Estonian history and art life of his time, what would you bring out?

Liisa Kaljula: I would say Ülo Sooster is an Estonian artist of the 20th century with a movie-like biography. A man who was born in the democratic Republic of Estonia, which was soon occupied by the Soviet Union that sent liberally minded art students to labour camps. But who, despite of spending his youth doing hard labour in the Gulag, still became one of the most important artists of the Estonian 20th century art history that not only created a unique artistic world but built cultural bridges between the underground circles of Moscow and Tallinn-Tartu that lasted until the fall of the Soviet Union. But what about you?

ET: I absolutely agree! In addition, I would say that Sooster is an ideal case study for the building more horizontal art history, which tries to expand canonical art history with its certain narratives, heroes and etalons, showing that very interesting and original processes have taken place outside the “art centres”. It is true that Sooster was very well informed about the artists and movements of Western Modernism, but the core of his artwork was not in playing through the experience he learned from the literature or saw at the exhibitions in the Thaw era Moscow like works of Picasso, Mexico Muralists or Abstract Expressionists: he was able to create a visual language and artistic philosophy of his own. Being created in Moscow, Sooster’s artistic legacy is also very closely bound to Estonian art traditions and developments, showing ingenuity of the local art scene and developments of its modernisms.

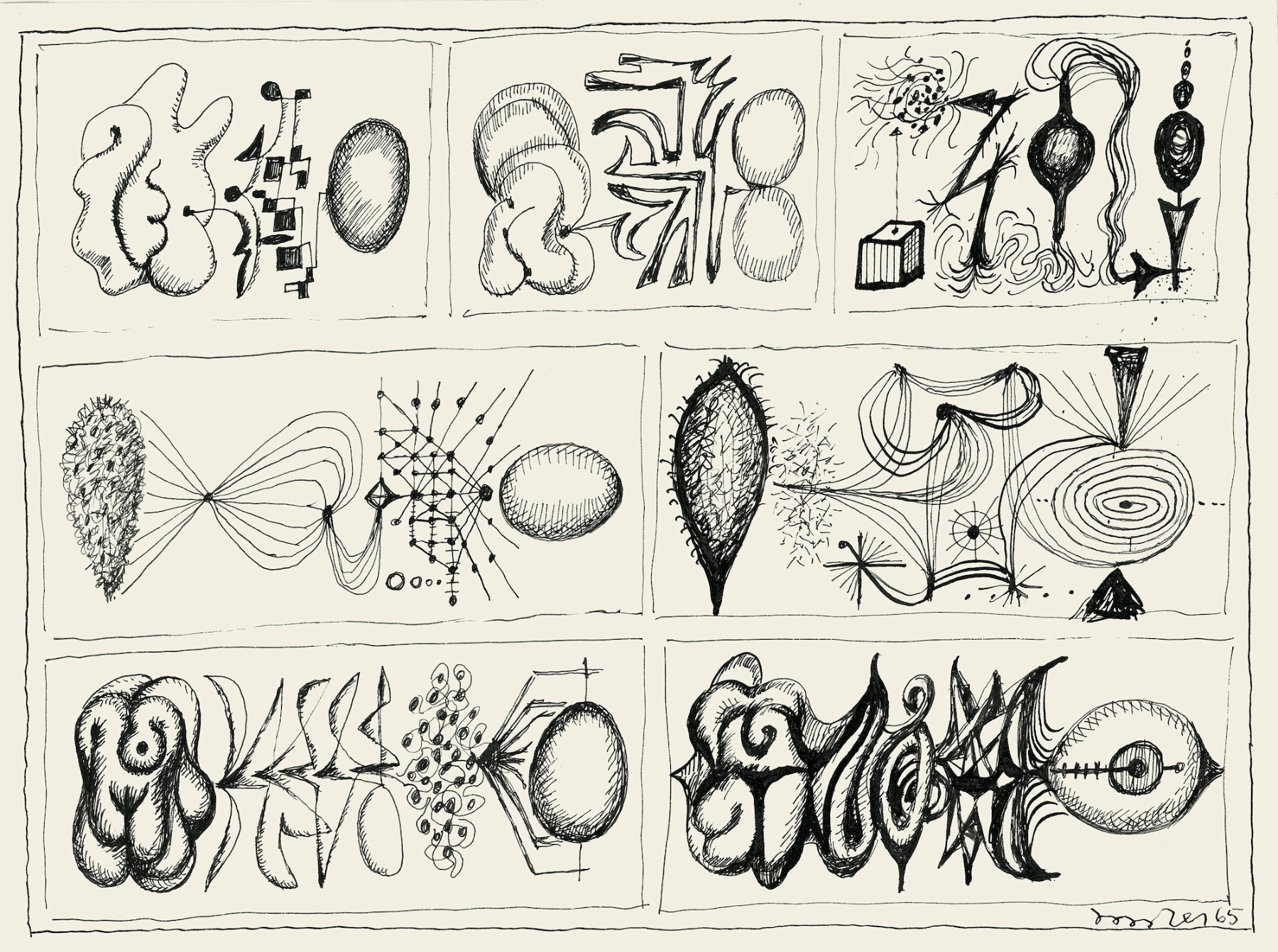

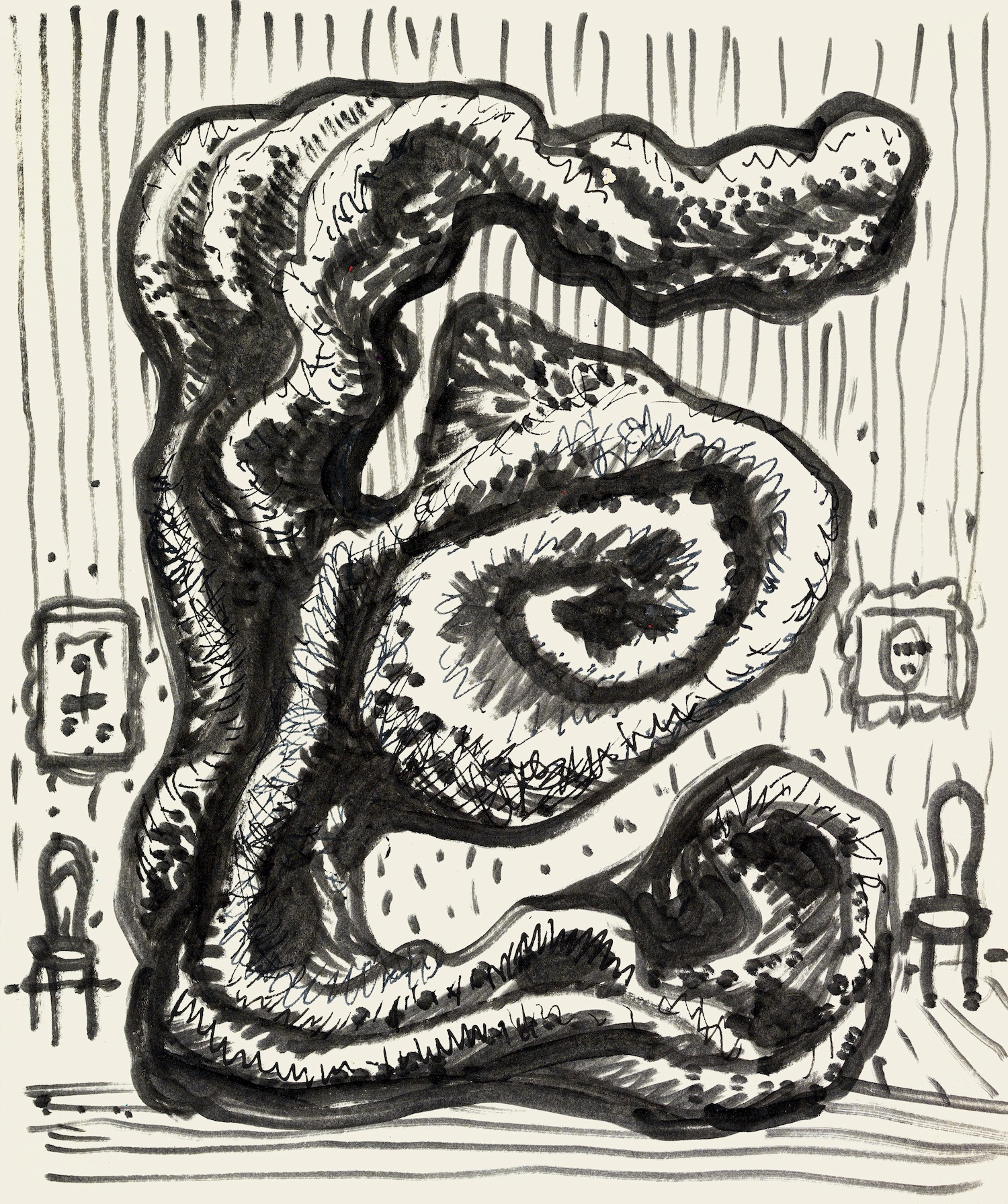

Ülo Sooster (1924–1970). Forms. 1965. Indian ink. Sooster family collection

LK: We tend to overestimate the meaning of our national cultures outside of our own countries, their export potential so to say. And not all the Estonian artists have what it takes to be an international artist. Do you think Sooster has got it?

ET: I think that he has both vectors in him. He took very Estonian archetypes from his childhood memories on the island of Hiiumaa – fish, egg and juniper –, but didn’t just treat them in some ethnographic manner. Sooster moved further, creating universal symbols, which can be recognised and interpreted in very all-embracing way. His mythological triad fascinates with their enigma, but at the same time they act as open signifiers, to which very different meanings can be ascribed – religious/mystical, philosophical, psychoanalytical etc. What would you say yourself about Sooster’s qualities of international artist? Can his unique painting technique be as enigmatic and hypnotising for a foreign viewer, who most probably doesn’t know the context that well?

LK: First, I see Sooster’s story as a great export article, especially now when our Eastern neighbour is again showing aggressive colonial ambitions in the region. His enigmatic author’s technique is also easily translatable for the European and American audience because it is very modernist in its essence: it wants to be absolutely unique, it wants to surprise, and it wants to enchant. And as its three leitmotifs come from Hiiumaa, which is one of the places in Estonia with the most beautiful untouched nature, it could introduce the country quite well internationally. However, the biggest challenge I see in introducing Sooster internationally, is how to explain to the Western viewers why modernism was still so important in Estonian art during the 1960s whereas in the West it’s the time when modernism falls under great scrutiny and criticism. But I am absolutely sure that Sooster’s humorous approach to Surrealism would melt hearts everywhere his art would go. It has that cuteness factor, don’t you agree?

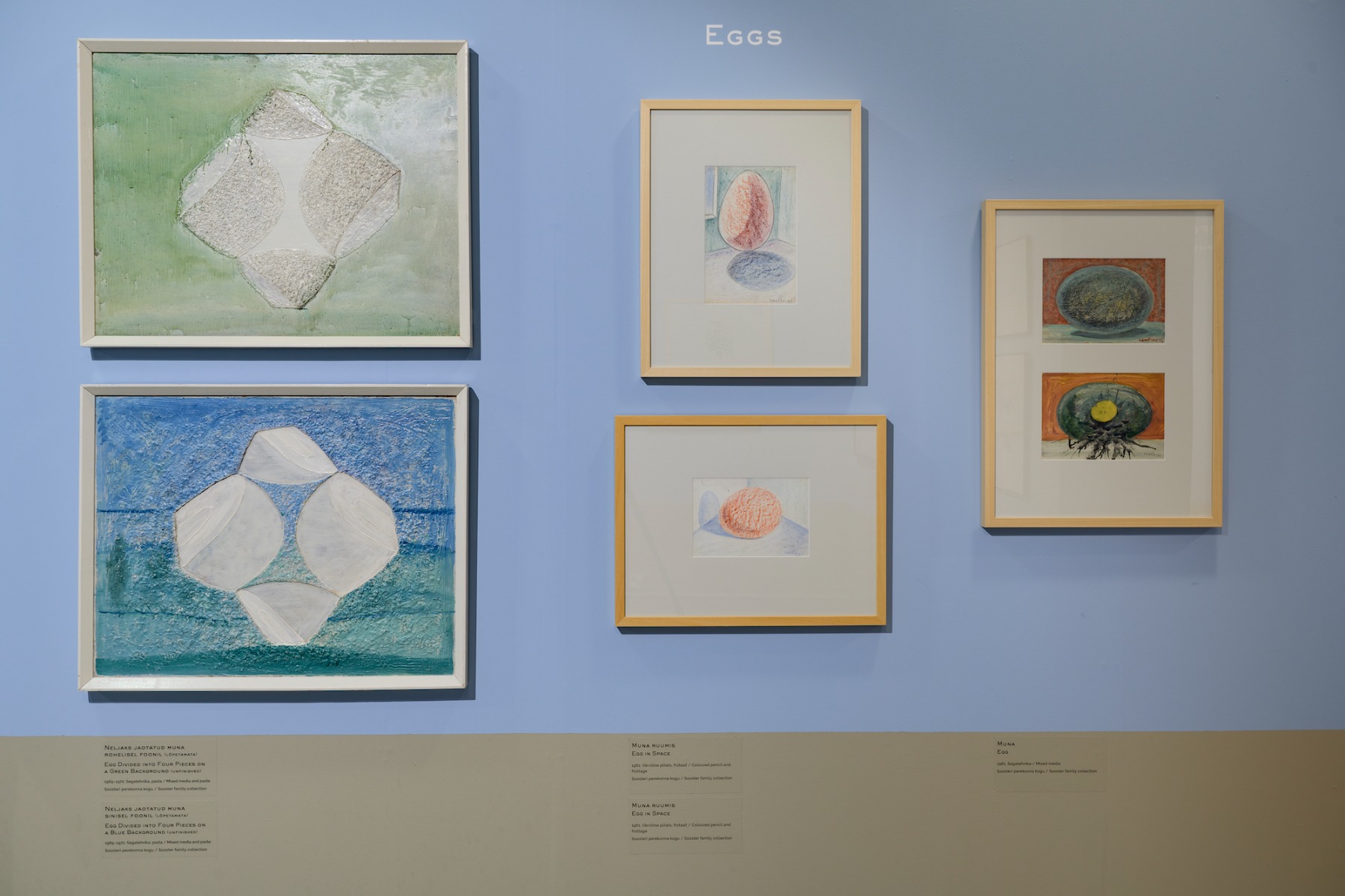

Exhibition view. Photo: Stanislav Stepashko

ET: Yes, absolutely! He has this very healthy, very benevolent sense of humour in his work, which is in good balance with serious philosophic, almost cosmological topics. Talking about his story, you have once brought out that Sooster dramatic fate reflects the fate of Estonia in the 20th century. Also, it reflects the history of Estonian art, where early modernism, represented by Pallas Higher Art School in the 1940s was forced to adjust to the dogmas of the Socialist Realism. Those who did it too formally or dared to hesitate, as Sooster and his student friends from Pallas period, were demonstratively punished – convicted in of treason of homeland in 1950 and sent to labour camps, mostly in Karlag in former Kazakhstan SSR.

By the time Nikita Khrushchev rehabilitated political prisoners, Sooster has already spend in the camp seven long years that could be his blossoming in creative and personal life. However, he managed to secretly continue his artistic practices and met his big love, Lidia Serkh (later Sooster) in the same Karlag camp system! After returning to Estonia in 1956, the former prisoner wasn’t accepted into the local art life, so the young couple moved to Moscow, where Sooster earned for living with illustrations. But it was impossible to show his creative works in official exhibitions (with an exception of the notorious Manege exhibition in 1962, in which Khrushchev berated a group of most experimental artists), which, in a paradoxical way, stimulated his experiments and freedom as an artist. Sooster became the artist we know and admire already in Moscow, being important figure in its underground art.

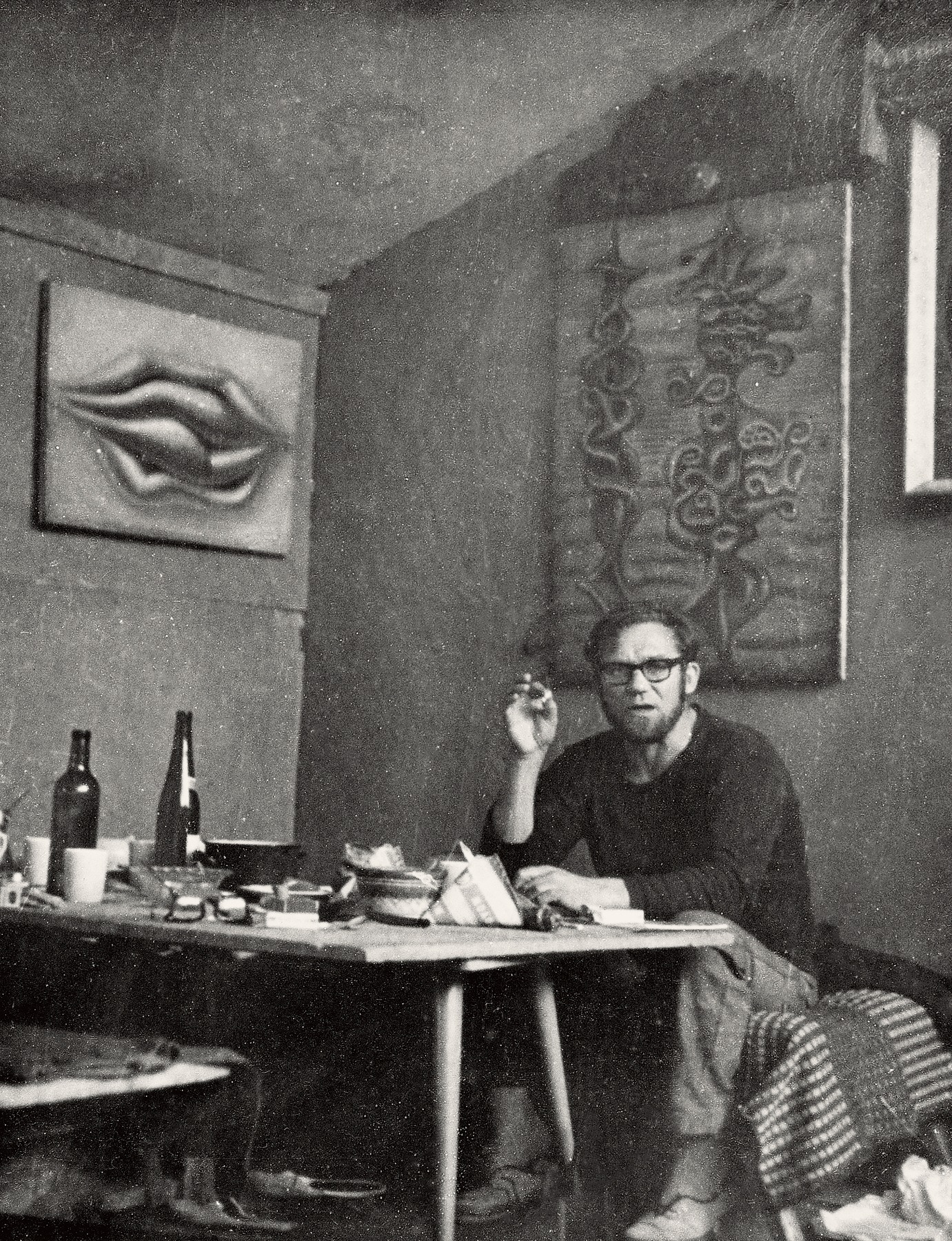

Ülo Sooster (1924–1970) in his Sretensky Boulevard studio. Moscow, 1970. Photographer: Jaan Klõšeiko. Art Museum of Estonia

LK: I am often thinking about how nobody knew anything about Sooster in Estonia in the 1960s, besides a small circle of artists and art historians in Tartu and Tallinn. Was there a moment where Sooster could have become a Russian artist? Like it happened to so many talented artists who ended up living in Moscow after World War II. Sooster’s close friend and studio neighbour Ilya Kabakov is a good example! Born to a Jewish family in what was then Ukrainian SSR, Kabakov together with his family moved in the 1940s to Moscow, studied art there and is known today as one of the most internationally acknowledged Russian artists.

ET: I think this possibility was quite real, as Sooster lived and worked in Moscow, so his main legacy was located there. Also, if I think about his legacy of a book illustrator, he was working mainly on publications in Russian and is quite well-known to Russian-speaking reader thanks to the huge print runs, but for Estonian broader reader he became known only after death and only from a couple of books that adopted his illustrations from Russian versions (like the classics of Estonian literature – Spring by Oskar Luts). Talking about his creative work, it was known mainly to his Tartu and Tallinn contacts as much as he brought himself to Estonia to show (and later often shared as gifts) or in his Moscow studio. What impression do you have yourself?

Exhibition view. Photo: Stanislav Stepashko

LK: I actually see it as a miracle that we can talk about Sooster today as an Estonian artist. When Sooster died in his Moscow studio in the fall of 1970, his family and closest artist friends were standing in front of huge dilemma: what to do with the enormous legacy that had accumulated in his studio? Lidia Sooster, being advised by Ilya Kabakov, Yuri Sobolev and a other closest friends of Ülo, decided that Sooster’s legacy needs to be tied with Estonia. And already in 1971, the first retrospective exhibition of Sooster’s work took place in Tartu Art Museum, after which the family collection was, piece by piece, brought to Estonia. But it could have ended up differently and considering that the big Russian art museums have not made much effort to collect Sooster’s work, it is clear that bringing his legacy to Estonia was the right decision. Here in Estonia, Sooster has become the key figure of the 20th century art, whereas in Russia he would have simply been one of the many artists of the multicultural Moscow underground. But it also leaves us with an enormous responsibility of course – to really work with Sooster and to also introduce him internationally as his work deserves and as he would have wanted himself.

Ülo Sooster (1924–1970). Interior. 1946. Oil. Collection of Mart Lepp

ET: I hope that our exhibition is a start in this process, as the core of it is namely the Sooster family collection. The display has so many different thematic sections – 15!, trying to show all the multifaceted experiments and searches of Sooster. What are the themes that are most important for you?

LK: For me, the series of self-portraits are important as a document of the complex history of Estonia in the 20th century: the early ones that are made in Hiiumaa during the Estonian Republic, then the realist ones that are made in Karaganda labour camp and carry the Stalinist imprint, and then the Moscow period where Sooster goes through a process of learning European modernism and as an outcome, becomes free from it to build up his own creative universe. But I also value highly the erotic works of Sooster’s legacy as these, I believe, are the most radical works that Sooster produced in the context of Moscow unofficial art of the 1960s. The art historian Inessa Levkova-Lamm, who was Sooster’s contemporary in Moscow in the 1960s, has said his cosmo-eroticism was his most important contribution to Soviet art and I have to agree with her in a way. Even though for Estonia, the junipers, the fish and the eggs are probably more important as this is what makes Sooster an Estonian artist who could represent and introduce the country also outside of Estonia. What are the themes that are especially important for you?

Ülo Sooster (1924–1970). Egg Divided into Four Pieces on a Green Background (unfinished). 1969–1970. Mixed media and paste. Sooster family collection

ET: I would bring out his abstractions, which is a very rich section – Sooster had so many methods for creating abstract imagery: biomorphic or geometric, playing with lines or ink spots, combining abstract and figurative regimes. Looking at those works, sometimes it’s even difficult to imagine that all of them were created by one artist. Sooster was constantly experimenting and looking for new ways of depiction, while for some artist would be enough to work with just one of those findings for the rest of his life. Another section, important for me, is related to dialogue of artistic and non-artistic imagery in Sooster creative work, which he enriched with experience borrowed from the books he illustrated – scientific publications or books of science-fiction. Here, we can see images reminiscent of anatomical, space or substance models, computing machines and graphs produced by them, views from microscope or telescope, while dialogue with fantastic literature was fruitful for depicting unearthly creatures and bizarre atmospheres. In the situation of visual deficit – like it was almost with everything in the USSR – Sooster managed to find an alternative source for visual inspiration. Also, I would like to stress sections which reveal proto-conceptual and proto-postmodernist thinking of Sooster – while thinking mainly within categories of modernism, he already anticipated some important elements of the new cultural paradigm.

Exhibition view. Photo: Stanislav Stepashko

LK: The exhibition in Mikkel Museum is dedicated to Ülo Sooster’s works in private collections, which inevitably contain lesser-known material. Some of the works in this exhibition are never shown before, so they really reveal the hidden side of Sooster. What was the main surprise that private collections offered to you as a Sooster curator and researcher?

ET: I think it was understanding how fruitful, versatile and diverse Sooster as an artist was – according to the opinion of his son, Tenno Pent Sooster, the legacy of Sooster consists of ca 200 paintings and 10 000 drawings. And this is only his independent work, as he created also hundreds of illustration designs – and died just at the age of 46! But what was surprising for you? You have worked much longer than me with the theme of Sooster and his Tartu circle, both with museum and private collections.

LK: To me, the richness of the Sooster family collection was a shock. To be brutally honest, it was quite exhausting to go through it all during the exhibition preparations, and it simply proves how big Sooster is as an artist. To spend time with his works from early morning to late in the evening and continue the same for several days in a row was hard because his legacy is very diverse and highly energetic. But I was also surprised, for example, by the quality and quantity of his juniper paintings in Estonian private collections, which simply proves that Estonians are a nation of nature and that landscape painting is still the most widely beloved genre among Estonian people. Besides, I didn’t think of Sooster as an artist who would interest women collectors, simply because I didn’t see the feminist side of his work before starting to write about it in the jubilee book. Sooster adored women and I dare to say that not only in an objectifying way! For example, he was very opened to the ideas coming from his female friends in the Tartu circle, who were remarkably talented and experimental, but for example, a lot of the male artists working in Tallinn would have never seen women artists as their equals, as their dialogue partners. I also strongly believe that the future of art collecting belongs to women, because women start to emancipate financially and are looking for ways to invest in art. We will soon talk about the female gaze!

Ülo Sooster (1924–1970). Arabesque at an Exhibition. End of the 1950s – beginning of the 1960s. Felt-tip pen. Sooster family collection

ET: Coming back to the idea of this interview to play with the Freudian couch conversation – what was the most frustrating experience while working on this project? In my case, I think, it was the urgent need to exclude so many great works, just because there wasn’t enough space for them in the exhibition hall!

LK: I also felt the contradiction between the small exhibition space and the enormous creative legacy of Sooster. And Sooster himself, I am pretty sure, was suffering from the same frustration: a kind of claustrophobia of the Moscow underground where artists were working feverishly to produce new body of work but could only show it in their ever-smaller homes and studios to the tiny circle of family members and friends. As the philologist Victoria Mochalova says in the documentary The Man Who Dried Towel in the Wind (2020, director Liliya Vyugina), the biggest tragedy of Sooster was that normal blood circulation of an artist who needs his audience was blocked for him in the Moscow underground.

Ülo Sooster (1924–1970). Three Green Junipers. 1966–1968. Oil and paste. Collection of Heiki Mölder

LK: We have talked quite a bit about the exhibition now. But what do think the jubilee book, published by the Art Museum of Estonia on the occasion of Sooster’s 100th anniversary, does to the Sooster reception? We are not the first art historians who work with Sooster, far from that – Sooster myth and Sooster canon existed long before we started our professional careers. And was it frightening to work with Sooster because of his position in Estonian and Russian art history?

ET: I must say that for me this research was preparing in some sense in an imaginary discussion with Russian art historians: thinking about importance of Moscow period, with its rich cultural life of the Thaw era, but also understanding Sooster’s Estonian background – all the education in art history and languages, as well as broad outlook in modernist art he got while studying in Tartu in the 1940s – university city with its French-like cafes, traditions of public discussions and mutual studio visits among the artists. That’s why for me were so important the works that he made during his study years and in labour camp – practicing elegant ink drawing and different methods in creating of facture, arriving to surrealist and abstract imagery already before Moscow. A great lesson for me from my previous project, coordinating exhibition Futuromarennia. Ukraine and Avant-Garde in Kumu Art Museum, was methodology of Ukrainian colleagues in decolonising their art legacy: not to saying that an artist, who was previously known as Russian is actually Ukrainian, but stressing the multiple national and cultural identities. I think it’s just the same we need to do with Sooster, because while already living and working in Moscow he continued to keep very strong connections with Estonia. Another important moment: materials from our exhibition and book suggest a good argument in breaking myth of Sooster as surrealist only, because he worked in so many different manners and methods! What was your experience in this question?

Ülo Sooster (1924–1970). Mona Lisa. 1960. Pencil. Sooster family collection

LK: I was of course in awe of both Sooster and the art historians who had worked with him before: Mari Pill, Reet Varblane, Eha Komissarov, Reet Mark, Tiiu Talvistu, Anna Romanova. Because in the end, we are talking about one of the heroes of the 20th century Estonian art history who survived the Soviet prison camp, introduced surrealism in Estonia, built cultural bridge between Moscow and Tallinn etc., etc. But the more I studied his work, the more I understood that Sooster’s reception needs renewal because art history writing has changed a lot since his last exhibition and catalogue was published by the Art Museum of Estonia in 2001. It has moved on from perpetuating the style histories of Western art centers and peripheral art historians need to be very inventive these days to create new discourses that could offer alternatives to the style histories written in the 1990s. Back then, writing Baltic art histories into Western art histories was of course existential as it really was important geopolitically to show that we are part of Western culture. Unfortunately, it is again important now, but writing Western style art histories is not enough anymore for joining global art histories, a lot of new intellectual work needs to be done on the local level, and it’s a hard and time-consuming work. I do not know if we managed to do all of that with our Sooster book, but I hope we succeeded at least to open up a greater variety of interpretive approaches and what you already mentioned – to decolonize his reception on different levels, to free him not only from Moscow centered art histories, but also from Paris centered art histories, using the knowledge and theories available to us now, in the 2020s.

Upper image: Ülo Sooster (1924–1970). Forms. 1965. Indian ink. Sooster family collection