“One Plus One Equals Three”

Interview by Skuja Braden (Ingūna Skuja & Melissa Skuja Braden)

A Q&A with Roger Buttles of Outer Space

Disclosure: Outer Space Gallery in Concord, New Hampshire is currently exhibiting Elizabeth “Grandma” Layton alongside Skuja Braden, the Latvian American duo who represented Latvia at the 59th Venice Biennale (2022).

Outer Space Gallery is an artist-run venue on the second floor of a historic home in Concord, New Hampshire, founded by artist and curator Roger Buttles. Influenced by Michelle Grabner’s legendary project space The Suburban in Chicago, Buttles built Outer Space as a deliberately domestic alternative to the white cube—a place where museum-level conversations unfold on couches rather than pedestals. His program centers on pairings: two artists placed in proximity so that their work forms a dialogue rather than a hierarchy, with careful attention to parity of presence, sightlines, and voice.

For this exhibition, Buttles brings together Elizabeth “Grandma” Layton (1909–1993) and the collaborative duo Skuja Braden. Though still largely unknown in the Baltics, Layton is an important late-20th-century American draughtswoman. After a lifetime of depression and personal upheaval, she began making self-portraits at the age of sixty-eight, developing a distinctive method of continuous contour drawing. With a single, unbroken line—often in colored pencil—she charted aging, grief, racism, misogyny, state violence, and care work with unsparing clarity. Journalist Don Lambert first championed her work in 1978, yet for years institutions condescended to it as “art therapy,” misreading emotional precision as naivety.

Skuja Braden—the long-term collaboration of Ingūna Skuja and Melissa Braden, who represented Latvia at the 59th Venice Biennale—work through porcelain. Their sculptures are vessels that function as bodies: sites of memory, desire, protest, humor, and care. Drawn imagery, over- and underglaze painting, and luster fuse surface and form into dense narratives of embodiment, sexuality, politics, and compassion. In their case, technical mastery and visual richness have often been used against them: dismissed as “decorative,” “kitsch,” or “too emotional” within conservative institutional frameworks, as if skill and seriousness could not coexist.

Seen together, Layton and Skuja Braden reveal how easily women’s truth-telling is misread—whether stripped down to a single line or poured into opulent porcelain. The pairing is not a visual rhyme but an ethical one. Both practices insist that beauty is evidence, that humor sharpens clarity, and that attention is a form of responsibility. Layton steadies a life through contour; Skuja Braden ask clay to hold the full weight of lived experience—the body as archive, the vessel as witness.

In the following Q&A, Roger Buttles reflects on how this dialogue came into being, what it means to hold parity between an under-recognized American draughtswoman and a highly visible yet misread Latvian American porcelain duo, and how a small, domestic gallery can host a conversation that feels globally and politically alive.

Elizabeth "Grandma" Layton, installation, Lines that Hold Forms, Forms that Remember,

Outer Space Gallery, Concord, New Hampshire 2025

Q1. What inspired you to create Outer Space and focus specifically on pairings?

Roger Buttles: The original inspiration came when I was in graduate school at the Art Institute of Chicago. Michelle Grabner—who is a great artist, critic, and curator—ran an exhibition space called The Suburban from her home in the suburbs of Chicago. She converted her garage and tool shed into a small gallery and invited artists to exhibit there. The idea was that you could show high-quality work outside major metropolitan centers like New York, LA, London, and so on. I found that really inspiring—that you could see work you’d normally only encounter in big art cities, but in a completely different kind of venue and viewing experience. So, I can’t really take credit for the original idea; it came from one of my mentors.

Having lived in major cities my entire adult life, I never dreamed of having an exhibition space, because I consider myself an artist first, and the idea of opening a gallery in Chicago or San Francisco or New York, where I’d previously lived, just wasn’t appealing. But when I moved up to New Hampshire during the pandemic and settled here, it was the first time since childhood that I’d lived outside a city, and it felt like this could be an interesting place to put on shows.

The idea of pairing artists came from wanting to create a dialogue. Outer Space is not only outside a major art center, but also a much more domestic setting—the gallery is on the second floor of an old historic home, and oftentimes there’s furniture and couches in there. I thought pairing artists would take some of the pressure off them, because it isn’t a solo exhibition. It isn’t meant to be just about one person. It’s meant to be about each artist individually, and about the dialogue between their work and the space. That was the initial inspiration: to create a conversation, not only between the artists and the room, but also outside of major art centers.

Q2. What do you hope pairings achieve—for artists, audiences, and the record?

Buttles: I hope to expand the dialogue between their work, their intentions, their voices, their inspirations—and create a more nuanced conversation. In a larger sense, I want to show that artists aren’t isolated. Yes, you might work alone in your studio, but you’re operating in a much larger context among countless other artists.

In this day and age it’s almost impossible to make something that doesn’t intersect with someone else’s work, or with historical and contemporary influences. I like the idea that artists are in conversation, even if they never meet—that they don’t exist in their own bubble, even if it sometimes feels that way when you’re alone in the studio.

On a practical level, it’s also about helping each artist in their career. I might be able to expand an artist’s network by exhibiting them together, so their followings intersect. That sense of community—artists helping artists, being generous and expanding networks—is inspiring, especially when one artist is more established, and the other is more emerging. I think that can be a beautiful relationship. Someone who has had museum shows or is in major collections respects and admires the work of someone who might be twenty years younger and still building their path. There’s no hierarchy. It’s just art, regardless of where someone is in their career.

So there are two layers: the motivation behind the actual artworks and the conversations they create, and the practical side of combining networks and opportunities.

Skuja Braden, installation, Lines that Hold, Forms that Remember, Outer Space Gallery, Concord, New Hampshire 2025

Q3. How do you distinguish between a pairing that is truly necessary and one that’s just decorative?

Buttles: When I come up with pairings, it’s a very organic process. I don’t try to be too rigid in my thinking. I have many lists of artists whose work I absolutely love, and there are infinite possible conversations between them.

I start from that groundwork: I genuinely love the work of both artists I’m pairing, so I already can’t go too wrong because I’m excited about them. Then I deal with very practical decisions: which gallery I’m working with, which artists are available, whether the artists like each other’s work, whether they want to show together, scheduling conflicts, and so on. If I were very rigid, I’d probably get frustrated, because so much is out of my control—and I actually like it that way.

It’s kind of like making an artwork. If I’m too rigid, if it feels like homework or building blocks, the artwork usually doesn’t turn out as well as it did in my head. So I treat curating these shows similarly: I have visions and ideas, but I have to stay flexible and “go with it.” I don’t always get to choose exactly which works will be exhibited—there are questions of inventory, whether a piece has been shown before, what the artist is currently working on. There are a lot of intangibles I don’t control. That’s exciting, because each show becomes a unique experience shaped by my ideas, the artists, the galleries, and the realities of the situation.

In terms of decorative versus necessary: I just want to show artists who have something to say. I don’t want to show work that feels like a product or someone repeating the same thing over and over. The artist has to say something inspiring or thought-provoking on some level—emotionally, intellectually, visually—that moves me. A good measure is: would I want to collect their work and have it in my house? And I can honestly say there hasn’t been one artist I’ve shown at Outer Space whose work I wouldn’t want to own if I could.

Skuja Braden, Ball and Chain, 2007

Skuja Braden, Ball and Chain, 2007

Q4. In a pairing where one artist is better known than the other, what do each of them gain—and what are the risks?

Buttles: The benefits are expanding their networks, having them show with someone whose work they genuinely admire, and creating a new shared audience.

As for downsides or risks, there haven’t been many, or at least nothing dramatic. The main sacrifice has been personal: I’ve invested more time in Outer Space than I anticipated, so my own art practice has taken a bit of a back seat recently. I’d like to rebalance that.

There are also practical risks: the cost of shipping work from across the country if there’s a pairing I really believe in, plus the usual challenges of organizing, timing, and scheduling. But I see those as the cost of doing this, not as downsides.

The biggest stress is the art market. If work doesn’t sell—from one or both artists—that weighs on me, because I really love the work I’m showing. I want it to go out into the world, not just exist in the show. When it doesn’t, I try to support the artists in other ways: documentation, interviews, videos, social media, helping their CVs. The risks are just the normal ones anyone takes on when operating a space.

Q5. What safeguards do you put in place so one artist isn’t framed as the other’s echo?

Buttles: I always try to create an equal showing. That doesn’t necessarily mean an equal number of works—some artists are more prolific or work faster than others—but I want the impact to feel balanced.

I would never want a show where it’s blatantly about one artist and the other is just a footnote, or only shows a sketch or study. There must be real investment from both artists. That’s a kind of quality-control guardrail.

I also try to promote both artists equally documenting all the work, sharing a video, and hopefully, in the future, doing catalogues. I never want one “main show” with a second artist on a side stage. For me, it truly is about one plus one equals three. I don’t think imbalance has existed in any show so far, and I’m always checking myself to keep it that way.

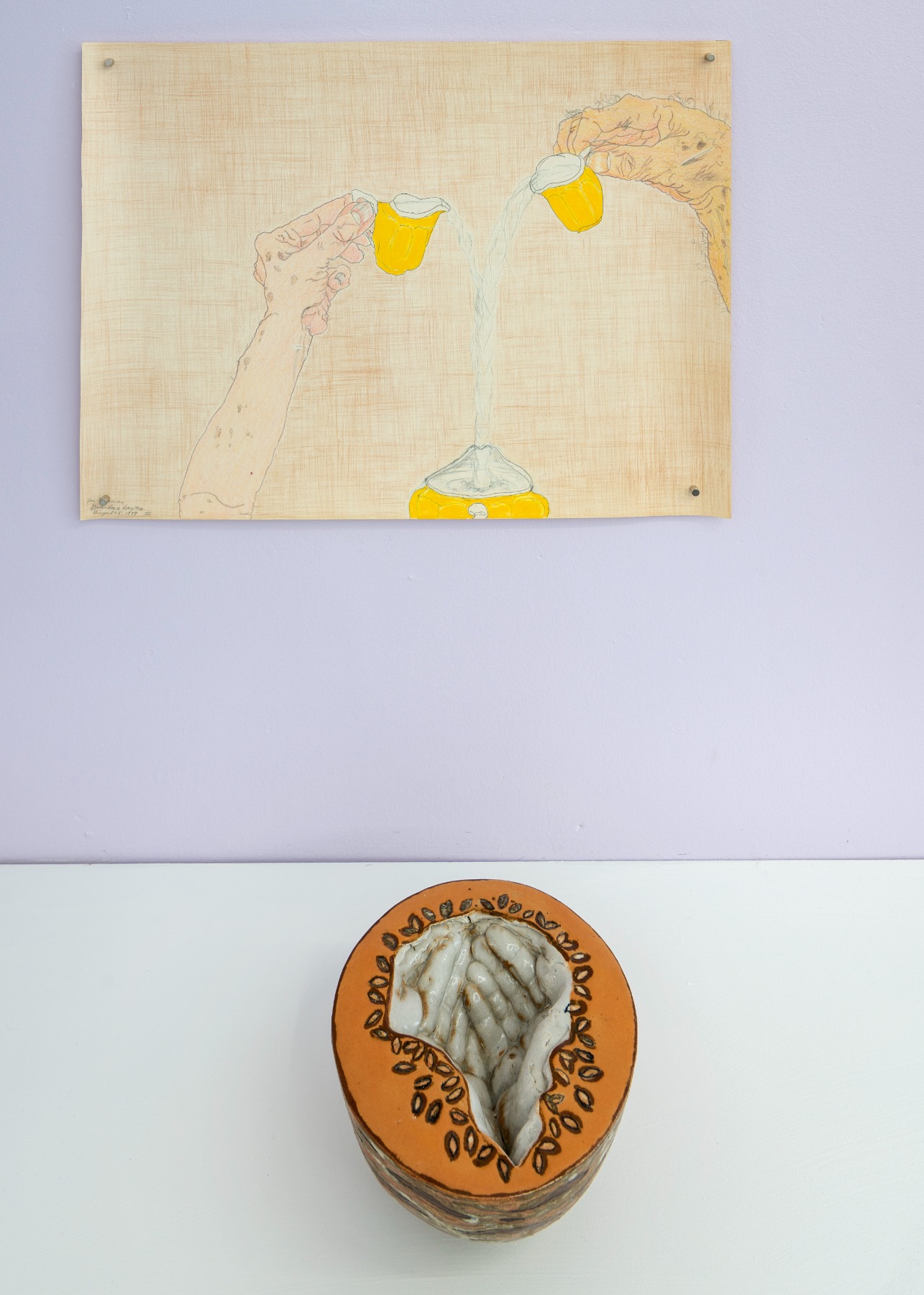

Elizabeth "Grandma" Layton, Two Hands Pouring, 1979

Skuja Braden, Begging Bowl, 2003

Q6. For this specific pairing, what shared questions or tensions made Layton × Skuja Braden feel right?

Buttles: I think the main question both practices ask is: What does it mean to be a woman in your time? For Layton, what did it mean in hers? For Skuja Braden, what does it mean now?

They address that from very different formal and historical angles. Layton’s perspective is that of a woman in the Midwest in the 20th century. Skuja Braden come from a European context and a different generation. But there’s a shared vision around strength, a feminist approach, a reckoning with how women have been treated historically and how they’re treated today.

I hope viewers feel that sense of empowerment. My mother, my wife, my sister are all strong women, and I believe in supporting that ideal. For me, that idea of liberation and empowerment is what really green-lit the show.

Q7. If you had to reduce it to one sentence: what problem does this exhibition ask viewers to face—and why do these two practices belong together?

Buttles: I think it asks: how are women being treated today—across societies and cultures—and what are we doing about it?

Their work doesn’t “need” each other, but they enhance each other. They offer two different perspectives on a similar topic, from different times and different mediums. That’s what makes the pairing fascinating, inspiring, and accumulative.

Q8. Which work, or pair of works, quietly unlocks the reading of the show?

Buttles: For me, it’s Layton’s Two Hands Pouring Water and Skuja Braden’s Begging Bowl. I placed them together very intentionally. In the installation photos, you can see it looks like the water is being poured into the bowl.

There’s a strong sense of give and take, of giving and receiving, of altruism. Within that, there’s sensitivity and empathy that I feel in both artists’ work—personally and on a broader, universal, even political level. Individually and together, those two works shines in a subtle, quiet, and sensitive way. They were a highlight of the show for me.

Elizabeth Layton, Don Quixote, 1979

Q9. When Layton’s line meets Skuja Braden’s vessel-as-body, what changes—for line and for form? What’s at risk if surface overwhelms volume, or vice versa?

Buttles: When line wraps around a vessel, it gains distortion, elongation, and warping of figures. It creates an unrealistic perception of the body and form, but in a powerful way. It also introduces time—because as the image wraps around, it eventually comes back to its starting point. You can play with this idea of infinity, or with a distinct start and stop when the imagery doesn’t run all the way around.

Placement also matters. Where you choose to put the image on the vessel changes spatial dynamics. I love how Skuja Braden play with that, especially on pieces that have strong differences between front and back—like the ballerina forms on the mantle. You can get weird juxtapositions, contradictory emotions, or sometimes symbiotic ones. It adds another dimension to their hand. I love their line on its own, but when you add the vessel, it’s even more impactful.

In terms of narrative and line, that’s true for Layton as well. They both have fantastic “hands,” by which I mean mark-making. When you combine that with narrative, it heightens the impact: you can enjoy the work formally and aesthetically, and then also read deeper into what’s being said.

As for risk, the only real one is if surface imagery becomes so overpowering that you forget the volume of the piece and start thinking it should just be a two-dimensional work. But I don’t see that happening here. Their use of volume feels very intentional and integral.

Skuja Braden, Daddy Long Legs, 2023

Q10. How did you approach installation—light, sightlines, text—so Layton’s planar works and Skuja Braden’s sculptural pieces stay in true dialogue?

Buttles: Outer Space has two rooms. Sometimes I separate the artists—one in the front, one in the back—if I feel their work is less visually connected. More often, I install both artists in both rooms, which is what I did with this show.

In this installation, the front room leans more into personal narrative, and the back room leans more political. With Layton, there’s a clearer divide between her personal works and her socio-political commentary. With Skuja Braden, those lines are more blurred; their works can often be read in multiple ways.

In this show, Layton’s works are all two-dimensional, and Skuja Braden’s are mostly three-dimensional, except for two wall pieces. I wanted to create groupings that flowed harmoniously—so in the back room I built a table grouping the cream-ground vessels with bright colors together. I also placed some of Skuja Braden’s more overtly political works, like the egg and chain pieces and figures that look like they’re screaming or crying, near Layton’s King Lear drawing. Those works connect really strongly.

This is one of the parts I enjoy most: each show is different, and there are countless decisions to make in order to make the works sing and connect. It takes days of thinking, looking, placing things temporarily, changing my mind. It’s never the same twice.

Q11. Can you name one work from each artist where volume and silhouette feel especially alive?

Buttles: For Skuja Braden, Mother and Child (2008) stands out. It’s a porcelain piece about eight and a half inches tall. There’s an image of a mother with a kind of cat-woman mask over her eyes, enclosed within what looks like a plastic bag. The bag mirrors the shape of the vessel itself, and there’s a beautiful interplay between the painted image and the actual form—you almost feel like you could reach into the vessel to grab the bag painted on its surface. The craftsmanship—the lips, the body, the bag—is just gorgeous. I was really excited when I first saw it.

For Layton, I’d mention Bubbles. It’s such an uplifting work. The way she renders the bubbles gives them real volume and airiness; you sense them floating. There’s also a strange distortion of depth—her hand reaches forward into the viewer’s space, while in the background there’s a fairy-tale-like castle. It’s strange and beautiful and volumetric all at once.

Elizabeth Layton, Birthday Flowers

Q12. What did you deliberately hold back from saying in order to avoid sentimentality (with Layton) or over-explanation (with Skuja Braden)?

Buttles: Generally, I feel the works should speak for themselves. I err on the side of withholding interpretation when I talk to people about art. I believe each viewer has a unique encounter with a work, the same way each listener has a unique encounter with a song. I wouldn’t want someone to explain the “meaning” of a song I love; I feel the same about art.

It can be interesting to have conversations about specific pieces, and that can add something, but I never want to be didactic or to say, “This is what this is about, and this is what you’re supposed to get.” I believe people can interpret and understand art in their own way, and there’s no right or wrong. If I can add a bit of context, I will, but I mostly keep my own interpretations to myself.

Q13. What should a first-time visitor understand only because Layton and Skuja Braden are being shown together?

Buttles: I hope they see that the works in this show were made by women with strong visions and deep commitment—artists who are passionate and intensely invested in what they’re doing. I hope that energy and strength of character comes across to viewers as it did for me.

That’s the connective tissue for me: a strong, passionate, feminist perspective and the gift of turning that energy into beauty.

Q14. How will this dialogue live on beyond the exhibition—and what might a museum do differently if it takes the show on?

Buttles: There are a few ways it will live on. The installation is documented, and each artwork is documented and presented on the Outer Space website and social media. There’s also a short video of the show. We recorded a conversation with Don Lambert, the journalist who first discovered Layton’s work in 1978. Any written publications will also be part of that afterlife.

And then there’s the less tangible part: the people who saw the show in person. For me, that’s what art is really about—how it lives on in those who experienced it.

If a museum were to take this show, or parts of it, I would hope they’d find new ways to install it that deepen the dialogue between these two artists—maybe in ways I didn’t think of or have the space to explore. That’s the beauty of it: each iteration would be unique, depending on the curator’s vision, the architecture, and the context. There are many decisions that could be made differently, and each would produce a new conversation.

Q15. Is there anything we didn’t ask that you’d like to have on the record?

Buttles: Honestly, I’m just grateful. It’s been a real pleasure to work with these artists, and with all the artists I’ve shown. I’m a big fan of their work, and it’s rewarding to bring them together and see people respond in the gallery.

You never really know where art will lead. For me, it’s led down a path I want to stay on for the rest of my life. And I value all the people I meet along the way—especially the artists whose work I get to share.

Title image: Curator Roger Buttles, installation, Lines that Hold, Forms that Remember, Outer Space Gallery, Concord, New Hampshire 2025