‘Not being an art object but inspiring them’

A conversation with philosopher, critic and lecturer Eik Hermann about the new building of the Estonian Academy of Arts

15/02/2019

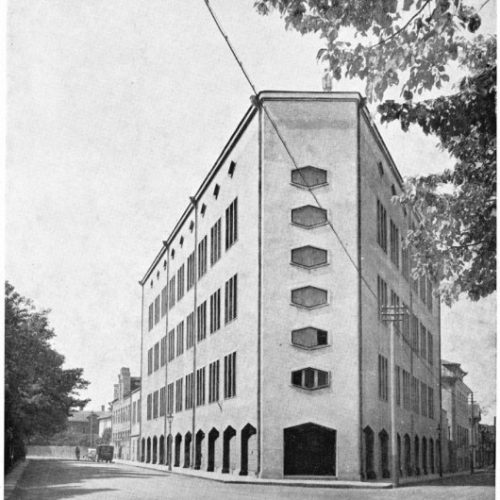

The Academy and its 1300-strong student body started this academic year in a new building in Kalamaja, a district currently experiencing a boom of development and located comparatively close to the Old Town and the city centre of Tallinn. Actually, it would not be quite right to describe the structure as completely new; rather, it is a conceptually reconstructed and ‘reformatted’ complex of old factory buildings, formerly housing production shops of the Suva sock factory constructed at various times. Following a lengthy stage of discussions and shortlisting of various solutions to the problem of finding a home for the Academy, the decision was made to reconstruct these assorted buildings, joining them to form a single educational complex. The history leading to this decision is quite a long one; there were proposals to move the Academy to the former sea fortress, a former mental and neurological hospital, the former public broadcasting centre; there was also the very colourful and dynamic project of Art Plaza. However, 2013 finally saw the decision made to choose this particular complex of buildings, the oldest one designed back in 1926 by the famous architect Eugen Habermann.

Factory building designed by Eugen Habermann, completed in 1932. Archive photo

The project was then taken on by the winners of the 2014 competition, the young and ambitious KUU Arhitektid office; they invited philosopher and lecturer (teaching philosophy to students of the Academy, among others) Eik Hermann to join the team working on the development of the concept. This was not the first time that architects were working with a philosopher, but this time the collaboration was particularly important. The conceptual intensity of the building, a clear understanding of its mission and multi-functionality of the solutions were highly significant here. The new Academy has six above-the-ground stories and an underground one; the net floor area exceeds 12 000 square metres; the construction costs totalled over 16 million euros.

Visualization of the project by KUU Arhitektid

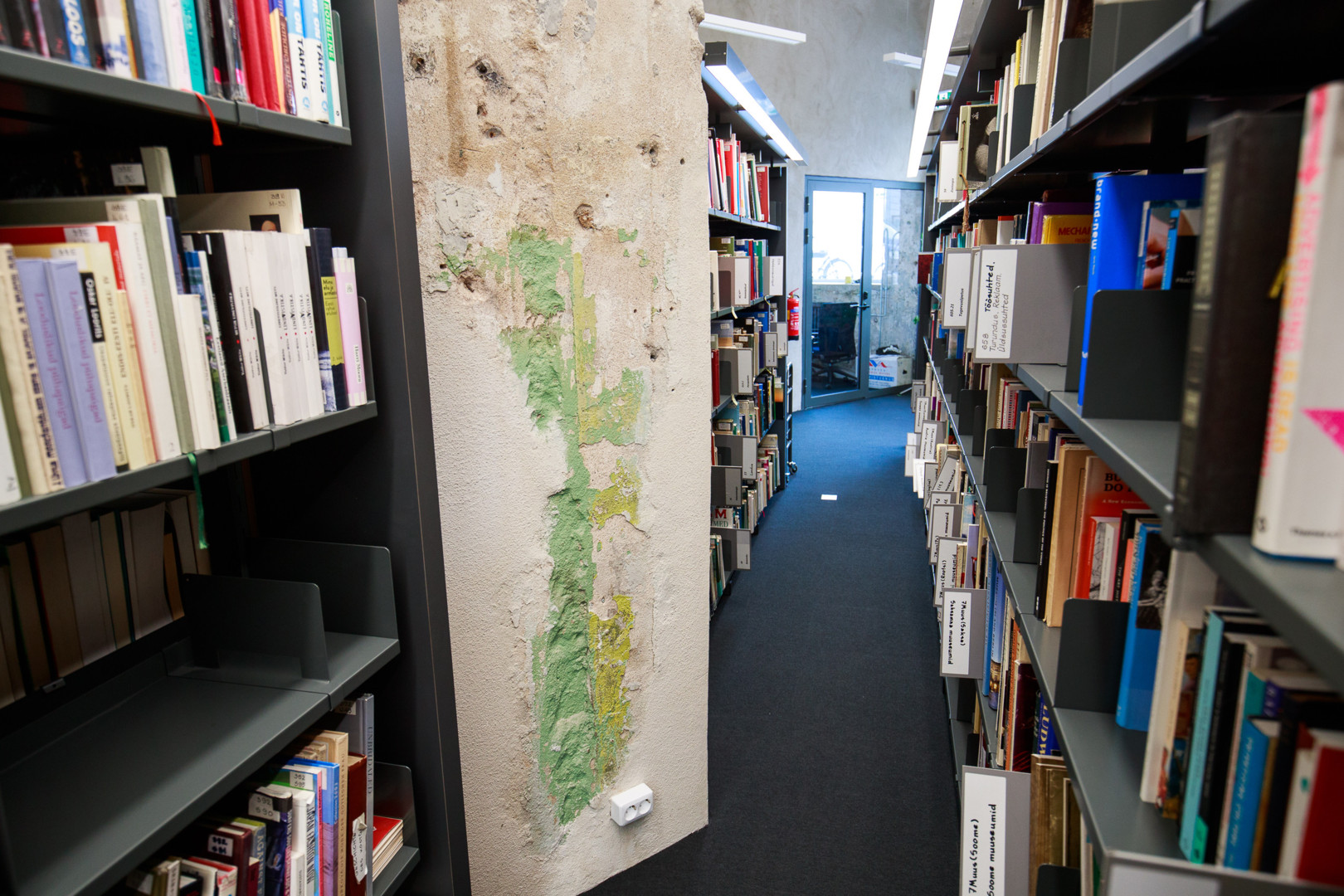

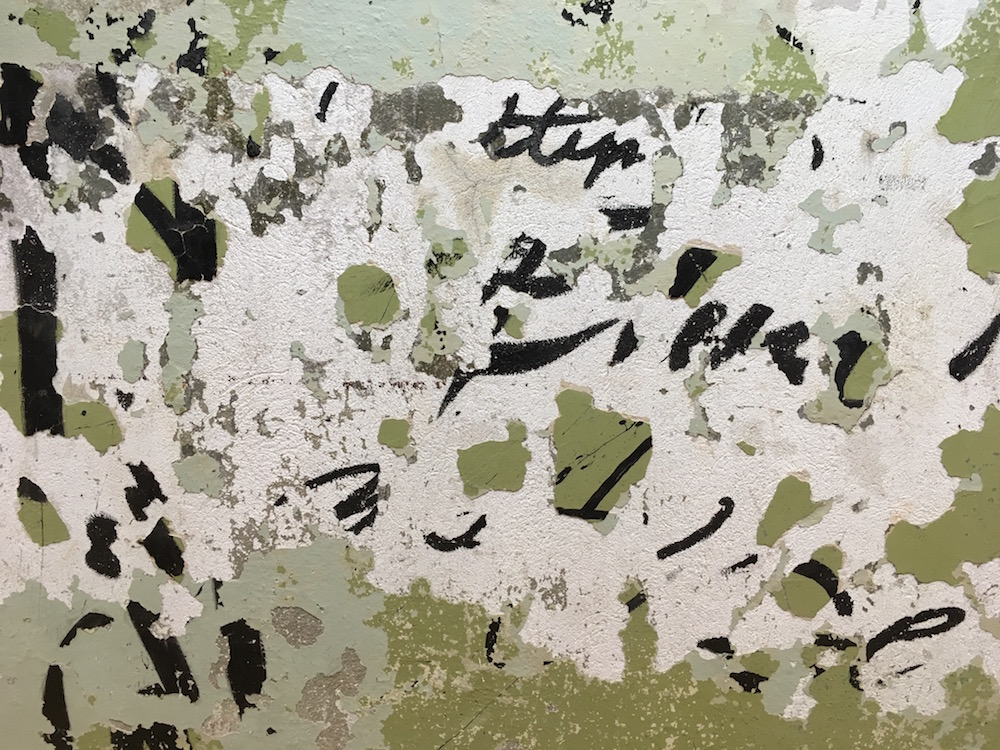

We were lucky to get Eik Hermann to take us on a one-and-a-half hour tour of the new Academy. It is a comfortable and very human-driven complex that has brought together a number of individual buildings and their respective stories, which is a fact that the authors of the project have made a point of emphasizing: several walls featuring half-faded signage and decor from the 1930s and factory-related inscriptions dating from the later Soviet period. ‘We wanted to keep as many of these layers exposed as it was possible,’ says Eik.

Visualization of the project by KUU Arhitektid

The post-industrial element is a constant presence here, helping create a feeling of a sort of ‘factory of art’, despite the fact that there is absolutely no sign of a concept like ‘production line’. The ambience is further enhanced by the wood and metal workshops, also the areas where architects build or glue together their models. The passage walls next to painters’ studios are lined with rows of fresh sketches; they can be viewed and discussed right here, on the spot. This is also one of the main ideas of the project ‒ the interpermeability of different faculties, the mutual fuelling, the synergetic coexistence. It is particularly important today when artists are constantly changing their media, switching from sculpture to video and back again, and the very spirit of contemporariness can be expressed as a complex multifactorial and multi-textured picture.

The logotype of the Academy (Eesti Kunstiakadeemia) on the reconstructed building. Photo: news.err.ee

Noticing new objects on the walls of the studios and passages, Eik is happy to see that the new residents of the building are contributing various things and ideas of their own. ‘It is quite a new building; we are only just starting to notice the new layers becoming obvious as a result of the students inhabiting the environment.’ As we walk out on the terrace with an impressive view of the Old Town rising above the city on top of a rocky hill, rosy in the sunlight of a frosty winter day, Eik tells me that one of the professors, a beekeeper in his free time, is considering placing a number of bee-hives there. We laugh at the thought that the bees would produce academic honey.

Moving across various spaces, studios, auditoriums for lectures and debates and different laboratories (there was even a TasteLab complete with some fairly good kitchen equipment), we talk about the new building, still to be made their own by the students, and the role played by Eik in the process of ‘inventing’ it. The following are some of the key moments of the conversation.

Eik Hermann. Photo: Artishoki Biennaal

What is your vision of the new Academy? What is the most important thing here?

Over the last 10‒15 years, all the faculties were housed in different buildings, in different parts of the city. They were disconnected; there was practically no communication between them. The decision was made to bring them all together under the same roof to make this communication possible and useful ‒ like a synergy. We never wanted to make this building as a sort of art piece; no, we saw it as a framework for art objects that were going to be created inside these walls. Not being an art object but inspiring them ‒ in this case, that is the mission of this building.

The budget of the project was very limited. The Ministry of Education said that it could provide 10 square metres per student. That is not much at all. For this reason, everything is quite functional here, and there is not a lot of communal space for contemplation and meetings. And yet we tried our best and we fought to have at least some space for things like that.

The main idea is also about the fact that people who study here are not that keen on absolutely finished we-know-better-what-your-space-should-be-like kind of places. They are free to introduce their own details gradually and change things. Although for me personally the end result still looks a bit too ‘finished’; perhaps we should have held back even more.

Photo: news.err.ee

How did your collaboration with the architects from KUU Arhitektid pan out?

The group of people working there are quite young; they are mostly thirty-somethings. I am forty myself. This was their first project of this scale, and many things had to be learned as we went. Although for me this was not the first time working with them on projects for competitions. The whole thing started as an experiment. My background is philosophy, but I have taught architects write their theses, undergraduate and graduate. And I started to learn more about architecture from working with them. I taught them to write, to structure their descriptions, their ideas for projects, and they told me things about architecture. The idea was born as a joke: perhaps I should write something about the way architects think. I was invited to get involved in two competition projects at two different architect offices. I did not find much common ground with one of the teams, a very experienced one, very sure about its decisions. With people from KUU, who were very young and open, we somehow instantly found the right balance. Our first collaboration was successful: we won the competition, and then we followed it with a string of other projects, including this one.

Photo: news.err.ee

How do you work with them?

I probably offer them a sort of different angle on things. But we are all equal in the process of discussion. There are four of us; we sit around a table, we debate, we sketch, while others simultaneously are working on models. Conceptual ideas and spatial solutions were really one and the same in this project. And in this case I was able to contribute more than usually because I had been teaching at the Academy for about seven years, and I had a good idea of what sort of space was better for lectures and what ‒ for making art or designing. And how to make the various forms of creating art influence and enrich each other, so that any student of, say, the Faculty of Architecture feeling stuck in his thoughts about a project could take a stroll around the building and look at what the sculptors of visual designers were doing, and it might just inspire him or her and help a bit.

When I was working with the KUU team, there were quite heated discussions, but we were of the same mind regarding the fundamental questions, for instance: is there a need to build a new structure or is better to reconstruct an old one? Another factor was the budget. It also prompted us to create spatial interactions that would have been impossible if we had simply offered a fresh building made from scratch.

Photo: news.err.ee

Were there any ideas that proved impossible to realize in the actual building?

I mentioned the budget and the spatial limitations. At the end of the day, there is still not enough room for quiet contemplation or simply spending some time alone. Everything is very open here. I think that the ideal version would be a combination of open, half-open and closed spaces. We were not able to create something like that here.

And there were also serious debates with several individual faculties. Some of the faculties were very unsatisfied with having to move to a space with a smaller area than their previous homes. And the only thing that we could propose was to view the situation as an opportunity instead of a problem. An opportunity of collaboration and cooperation.

Photo: news.err.ee

When you exist separately as an institution, inevitably certain parts of the structure emerge that could actually easily be shared with someone else... But there is another thing I wanted to ask you about. There was recently quite a stir in Latvia when it was announced that the building of the Latvian Academy of Art could now be accessed only with magnetic cards. The decision was explained with impossibility to track down and prevent theft in the building. Whereas here in Tallinn I entered your Academy freely and could spend some time at the café or visit the library on Floor Zero.

Yes, we had a similar discussion. And it is true that the building can be freely accessed via one of the two entrances, but there is another one that can only be used if you have a card. And we as the authors of the architectural solution cannot feel happy about it. Without a card, you can access the central part of the building where all sorts of performances, talks and concerts are frequently held; however, the rest of the building ‒ the studios and other facilities ‒ can only be accessed with a card. Another thing ‒ we wanted the part of the building housing studios open for the students 24/7. So you could come and work here at any time. The rector’s office decided that the building should be closed at 23:00. The students are currently voicing their opinion, and 320 of the 1300 have already voted against the decision; that is almost a third of the students. The rector’s office intends to keep the building open 24 hours a day at the end of the term, before the exams and tests; we will see what happens afterwards.

Photo: news.err.ee

Are there any plans of extending the building? Perhaps creating some adjacent ‘warehouses’ for storing, let’s say, the architectural models?

There are plans, and negotiation about acquiring some adjacent buildings are underway.

What else should we pay attention to in the new building?

Its acoustics, for instance. These are mostly concrete structures with a serious echo problem typical for this material. A huge effort was made to ensure that the sounds and noises of the various activities would not disturb the work of other people and overwhelm with their intensity.

Photo: news.err.ee

Did you travel to other countries while you were working on the project of the new Estonian Academy of Arts to familiarize yourself with the experience accumulated building similar structures?

We did make a Scandinavian ‘tour’ ‒ that is what we could afford. We visited Stockholm, Malmö, Gothenburg, Oslo, Copenhagen. It was at the time when we were pondering the question of ‘openness’ and ‘privacy’ of an educational establishment. We were trying to find the best balance between the two. And some of the schools were very open, like AHO, the Oslo School of Architecture and Design, where all the studios are housed on the same floor; it is basically a large communal space. On the other hand, in Malmö, where the building is a relatively old one, each artist was working in his or her separate little room. Which is a completely different approach. Oslo and Malmö are the two opposite poles of the situation. Somewhere in the middle between the two was the Academy of Art and Design in Copenhagen which was a combination of the two approaches. And in all these places we spoke with the students to understand the advantages and disadvantages of the existing solutions. In our case, though, the spatial limitations made it impossible to implement our ideas and accumulated experience to the full. For instance, on the fourth floor, housing the students of the Faculty of Architecture, we were forced to make a huge open-plan space; there were no other options. If we had more space, we would have definitely created more space for contemplation and solitude...

Is there currently a new movement in philosophy that could, in your opinion, influence architecture?

Perhaps object-oriented ontology. I cannot say that it is very popular among our students, though. I would rather say they are reading a lot about ecology and ecological thought. Personally, I like Deleuze, Guattari, Foucault, the old French thinkers better. And I must say that Deleuze was not very successfully and accurately interpreted by architects.

Photo: news.err.ee

I recently met Daniel Libeskind in Vilnius. There was a time when he was very much associated with the deconstructivist movement in architecture, the point of departure for which was Deleuze. It seemed to me that Libeskind is now distancing himself from all that.

When I mentioned an inaccurate interpretation of Deleuze, I was referring to marked formalism while disregarding the social aspect of his ideas. It has very much to do with the phenomenon of ‘starchitects’.

Libeskind was talking a lot about the human meaning of his projects... Of course, the question remains ‒ is it actually always present in the buildings that he has designed?

The same question occurred to me. Yes, you can say all these wonderful things, but I do not see them in real life. In this sense, there is a gap between the theory and practice; they seem to lead separate lives.

Fragment of a wall preserved in its original state after the reconstruction. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Are you working on new concepts withKUU Arhitektid?

We worked so long and hard on realization of this project that there has not actually been any mention of future collaboration, but we have already discussed some ideas... We will see what happens next.