Soft Baroque. The weird things of this age

The Soft Baroque art duo makes objects we could not have imagined before that, changing our perception of the actual non-materiality of image

04/11/2019

They explain in one of their interviews: ‘We come from different backgrounds. Nicholas from traditional furniture making and [Saša] from visual art, which works really well for us. Nicholas is the hands and [Saša is] the eyes, but we share the same body that thinks alike. [They] bring different skills to the table, yet [they] are interested in the same ideas (although [Saša] often draws things that wouldn’t hold together in real life).’

Meanwhile the website of the Copenhagen Etage Projects, the art gallery representing them, says: ‘The design duo Soft Baroque blur the boundaries between acceptable furniture typologies and conceptual representative objects. Trained in furniture and graphic design respectively, they explore objecthood and the perception of materiality in the age of digital image cultures.’

What does it mean? Perhaps that Saša Štucin and Nicholas Gardner are two of the most interesting artists of today, subtly working with the ways in which our reality is changing and attempting to a certain extent to influence these changes. They are doing it with the help of completely ordinary things ‒ tables, chairs, benches. These objects are shown at galleries, museums (from V&A in London to Depot Basel) and design forums, but at the same time they can also be found at somebody’s home or in a luxury store. In most cases, they can be used to do the things they are normally intended for, and yet first and foremost they excite our imagination and question the ‘permitted boundaries’ that we attribute to objects. Can a mirror be a cloud of aromatic mist? Can a hat be a miniature fountain or a waterfall? What do we see when we look at a silk fabric on which the visual surface of marble or granite has been printed?

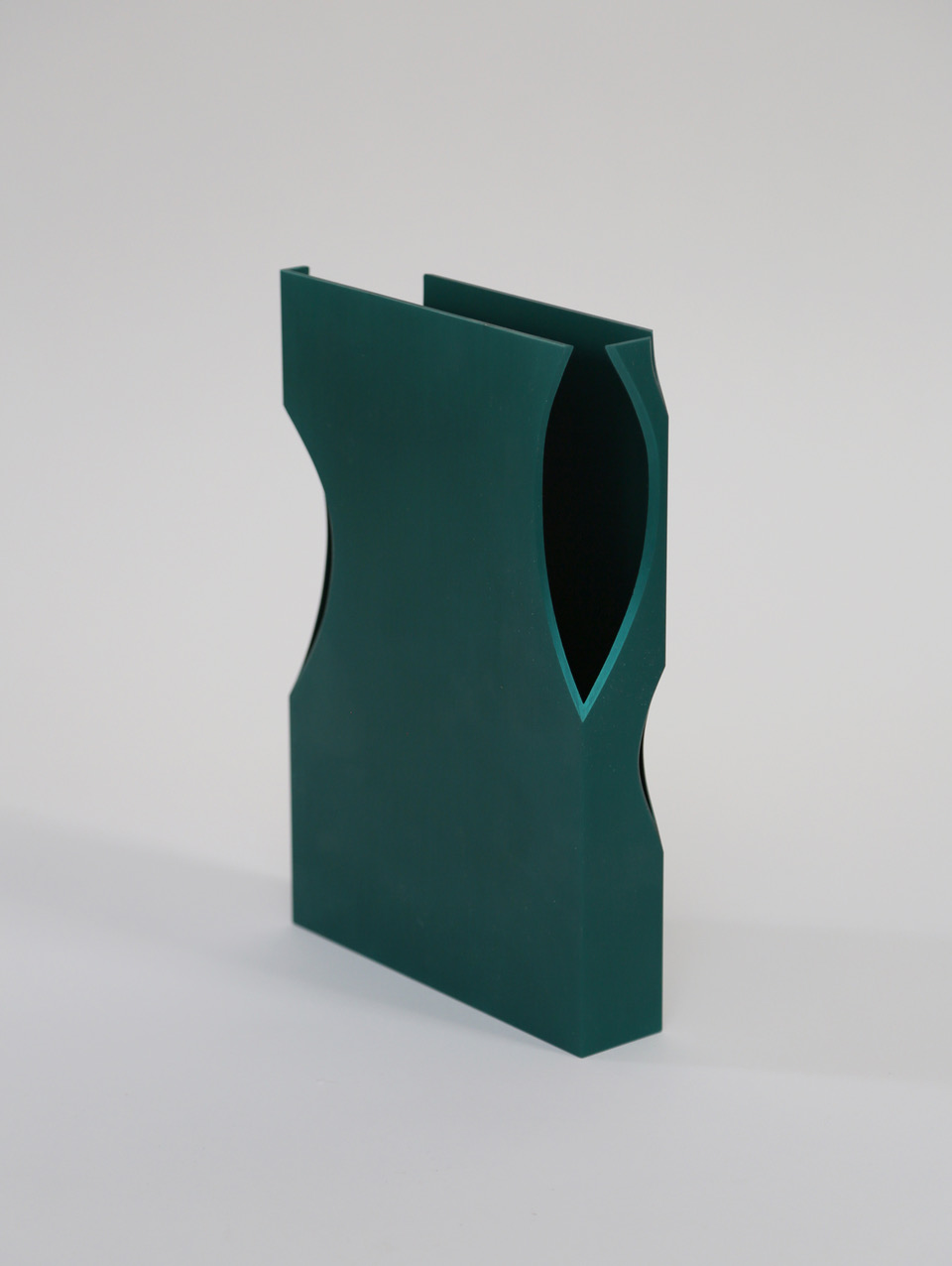

Corporate Marble Vase. 2019. From exhibition World of Ulteriors. Photo: Etage Projects

Speaking about future is becoming less and less popular in our world, because the actual reality is so fluid and mutable that it is very difficult to understand, which of the things in it are just for today and which ones will roll over to tomorrow. And it is on this thin line, this visual nerve of the contemporary age, undoubtedly, hugely influenced by digital consumption of information, that the majority of their objects, a combination of avant-garde design and conceptual art, are based. It is a certain litmus paper for the contenporary age and our visual understanding of it.

Thanks to a brilliant stroke of luck, there was an opportunity to invite Saša Štucin and Nicholas Gardner to visit Latvian in mid-August, namely, one of the country’s most beautiful locations, Sigulda, home to MAD, the annual summer school of design. Set right next door to Sigulda Castle, a huge transparent pavilion hosted an international team of students, young artists an designers, all of them busy moulding, chiselling, glueing and constructing something. Soft Baroque presented a talk and closely worked with the students on their projects. We met with Saša and Nicholas on the eve of the last day of the summer school, when projects were all nearing their completion, and there was time to sit down in an open-air café in the park, a few dozen metres from the pavilion, and talk.

Saša Štucin and Nicholas Gardner at the annual summer school of design MAD in Sigulda. Photo: Rihards Funts

Saša is from Slovenia, Nicholas ‒ from Australia… And you met in London?

Nicholas: We were fellow students at the Royal College of Arts, except we worked in different directions. Initially we started doing things together, realising all sorts of small-scale ideas, making separate projects. Saša was more interested in 3D objects and a distinctly sculptural, installation-related approach, whereas I was focusing more on the practical side of things. And in this difference of interests a very important conceptual rift was present: all our works feature a certain contradiction… or somehow oppose the mainstream. In any case, we simply started working together. And the name Soft Baroque was something like a pseudonym, something like a term for a fake style trend, which was how we imagined ourselves. As if it were a powerful artistic movement with almost religious followers; after all, modernism also used to be something like a religion. On the other hand, there is this allusion to soft power, to software as opposed to hardware, a hint of the new technologies. It sounds like a contradiction in terms, while at the same time harmoniously speaking of our time, of what it is like.

Saša: Yes, we do like this kind of contradictions and juxtapositions which may initially seem alogical. But when you think about it, some kind of different meaning seems to emerge. Many of our works are close to this in spirit. And it can sometimes be a very simple, pure and exquisite object, but there is always something more behind it.

It is more or less clear regarding the ‘soft’ part, but which elements of baroque do you find so appealing that you decided to use this word in the name of your project?

N: I think that we are interested in how decoration, ornaments, unusual surfaces or materials can give a different value to an object. Today, in this consumerist era, much closer in spirit to baroque than anything ever before, there is this stamp of artificiality on any product, granting them a higher status. In London, for instance, laminate flooring is very popular; it is, essentially, plastic, covered with a very thin layer of decorative plywood, made to look like old wood. And so this very common laminate acquires value and cultural significance. It is also a sort of cultural capital, although a very cheap and superficial association working here, of course. I think that, in our time, we invest more means into adding this decorative aspect to everything in the world than into the actual production of things.

S: I also like baroque as a metaphor. After all, if you look at the history of art, baroque is the most misunderstood and misinterpreted of its periods. Many, without giving it another thought, would define the trend of baroque a something over-the-top, something too decorative; but if you look deeper, it is almost the opposite. Baroque is very theatrical, with some dreary notes…

N: Grotesque.

S: Yes, grotesque. And I like it a lot. Even if baroque was used in the functions of the church and some sort of social framework of the time, there was still this internal creepiness present in it. Like it was with Bellini and Caravaggio ‒ in all of their works, commissioned by someone, there is some grotesque, there is a powerful expression of their own ideas. And that is my kind of art. I am saying all this to make the point that baroque is being totally misinterpreted…

Coffee table Malaparte, inspired by Casa Malaparte in Jean Luke Godard's film "Contempt" (1963). Photo: Soft Baroque

We recently published an interview with a group of artists from Russia, AES + F, and they said we were living in an era of neo-baroque. What they meant was a total general visuality and combination of styles from previous eras, which today are used only as visual decorative elements.

N: We have also thought and spoken quite a lot about ‒ in a sense ‒ the death of style trends and movements, for instance, in design. We no longer move form one idea to another; it is more like a multiplication of styles. In this sense, the world is so full, so rich in content ‒ good or bad. There is such an incredible variety of styles and tastes that, even there is some agglomeration taking place at some spots, on the whole it is very much scattered.

And there is this thirst for something that excites or attracts attention, dynamic or convincing in its own way, and, at the same time, craving our attention in its own way. We love to play with it in our works, for instance, make something very dynamic or optically strange. And at first glance we think ‒ yes, that’s classy. But for us it is also about objects needing to be more and more provocative, screaming at us, demanding our attention, securing it with increasingly devilish means. And we play with it, and, to an extent, also critique the things that are gong on. We often take some tasteless things and replay them on a more artistic level.

Lenticularis. Photo: Soft Baroque

Is something new, the very idea of something new possible in this world, where there is already so much of everything? Or can we reach it only through hybridisation of what already exists?

S: Of course, we often work with something familiar and customary, adding a completely alien element to achieve something new… But we also think a lot about our world as an opportunity for new manners of behaviour and customs to emerge; we try to imagine new types of personality or some new needs.

We have series of works where we deal with the idea of recontextualising the landscape of domestic environment. For instance, we made a mirrot with a moisturiser on the back and perforated surface, so that the result was something like a cloud of fog, and the cloud is also perfumed at that. Sp when you look in this mirror, expecting to see a clear reflection of yours, you are wrapped in fog instead. We sort of contradict the normal function of a mirror, creating a new type of personality that will go on using this object in a completely different way.

N: I think that your question could be answered by saying that we aren’t looking for anything like the perfect solution. We try to question the various functional structures that already exist. For instance, everybody has a sofa at home, everybody has a table, and if we change this familiar landscape of the domestic environment, it can, in its turn, influence the way we behave in this space. So in a sense, we act like traditional industrial designers do ‒ we think about functions, materials, about how this or that thing is perceived in human culture. But we also have another programme of action ‒ disrupt or destroy this traditional, not necessarily traditional but existing form and functionality. You cannot always hope for success here; sometimes we just throw things into it and look how they are doing. And sometimes it works.

On the other hand, in our time, we all need more understanding ‒ what is it that we let into our lives, what are we investing in, what sense does it all make? And the thing that we do ‒ we sort of try and make the muscle responsible for that work; we try to not let it become lazy by constantly exercising it. What does this object mean and what is its meaning in the existing consumerist society? And the whole thing is not about some sort of imaginary scenarios; it is about things that happen in the world around us.

S: With its Amazon Prime, Alibaba and Ebay. That’s reality, too.

Fragment of the exhibition World of Ulteriors at Etage Projects gallery in Copenhagen. Photo: Soft Baroque

Something like a muscle for responsibility for objects…

S: Yes… Nick is already tired of what I’m saying. But I often treat our objects like pets, understand, because they are silent. But they do not blend with everything, like an IKEA table. They are by their nature quite determined statements. And I see them as something like companions, like some sort of half-living creatures with quite a dominant existence. It is like that cat you have at home ‒ someone who lives by your side.

Living objects?

S: Perhaps… In any case, they do have an aura of sorts. (Laughs.)

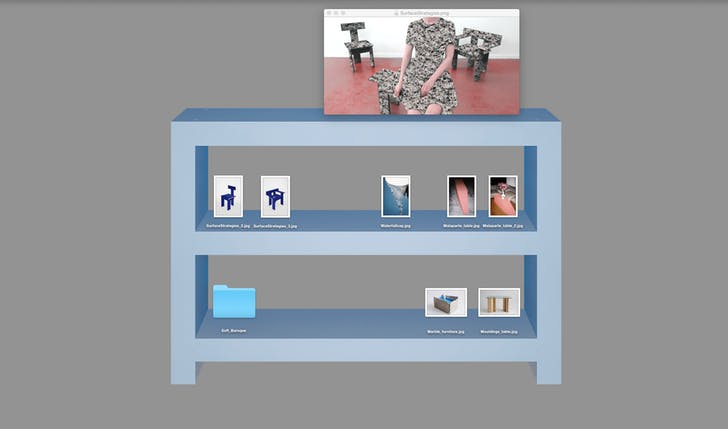

Desktop shelf. Photo: Soft Baroque

How did you manage to achieve a situation that your objects are at art museums and galleries, and at the same time ‒ at places like Balenciaga luxury stores?

S: I think that we gave to thank the few people from the previous generation who promoted this idea, and we, in our turn, also are expanding space for the next generations. When we started, the very idea of showing designer objects at a gallery was still somewhat weird and uncustomary. And many people did not take it seriously, particularly fine art people. But now it has already become more familiar; increasingly more people are taking interest in these things that are ‘between’ the usual formats. Initially I felt very uncomfortable when people asked me, for instance ‒ ‘Who are you, a designer or an artist?’ As if I really had to choose between the two. As if you could not be both at the same time. But our works do not fit within the parameters of design. It would be very problematic to mass-produce them; they are handmade, and because of the way we make them, they cannot be produced as an edition of a thousand. These things are unique.

At that, I do not see myself as a pure artist. In my practice, I don’t so much make statements about myself as comment on my environment.

N: Perhaps we could describe ourselves as artists who create works about the design industry and the consumerist culture. That is, of course, also a very cheesy description.

S: Nevertheless, it places ourselves into this position of in-between, somewhere in the middle.

N: You could say that we are artists, but our means of expression, our medium is functional objects. Instead of canvases and paint, we use furniture objects and similar things…

And the same object can be not out of place at a gallery…

S: …and at somebody’s home, and at a Balenciaga store.

From Puffy Bricks series. Photo: Soft Baroque

You work with various materials, some of them quite futuristic or recycled…

N: Yes, we sometimes also use recycled plastic, but generally what we like more is the idea that materials with some sort of established identity of their own suddenly end up used in a completely different manner. For instance, carbon fibre ‒ it has this very masculine connotation to it, it is all about the ultimate high performance. But we add a non-systemic chaotic note to it ‒ we combine it with something that would not normally be associated with it, like bamboo or pearls. Masculine carbon fibre with feminine beautiful pearls and bamboo ‒ a sort of pseudo-eco-friendly material.

These three materials can actually co-exist perfectly well in someone’s home: the pearls ‒ among jewellery, bamboo ‒ in the shape of a table, carbon fibre ‒ as a kayak or skis. But when you combine them within a single object, it speaks of a different value system that you put into it.

S: Оf symbolic value. And we often also like to emphasise this contrast, to enhance it. When there is such a diversity of materials all around you, there is always this relentless curiosity eating at you, this desire to try something else. But, like Nick says, we use these materials as our language. We live and work in London, and you can find anything you want there. At the same time, we are very far away from natural sources of material. If we lived here [in Sigulda], we would probably work with what is around. In this sense, there is not a lot to lean on in London. Everything has been in one way or another brought from somewhere.

From New Surface Strategies series. Photo: Soft Baroque

But you are both also from two very different corners of the world, both quite distant from London, and each of them has its own special background and its specific materiality. How do you combine them in your works?

S: We have been living in London for nine years. Of course, we go back home all the time; I go to Slovenia and Nick goes to Australia. But we have nevertheless already settled down in this in-between universe where we take something from one place and from another.

N: Perhaps your background was more image-related than mine.

S: But that has not that much to do with the fact that I am from Slovenia… Although it was in Slovenia that I graduated from the local Academy of Art, where I dealt with images, of course, and Nick went to furniture-making classes back in Australia. So we really are coming from different areas in a sense.

N: But that also led to us working with images as a material, using 3-D. We even made furniture from them. And I generally like this idea of image as a new material.

S: Yes, we make prints of marble surfaces and glue them on plastic, and then we build structures that look like real marble. And then the question arises of which part is image in this and which ‒ materiality?

N: It is generally a very large part of out visual landscape, all these giant banners, and it is mostly advertising, of course. But even in a small greengrocer’s, for instance, they would rather glue an image of a huge tomato or a strawberry than simply leave it clear. Or you could mention the scaffolding wraps used in London to shield buildings under construction. Developers print out these life-size images of interiors on these covers, as if on the outside of the upcoming buildings, to advertise the interior, in other words, what is going to be inside.

The visual landscape is increasingly acquiring high resolution features. Representations, photographs, images occupy an increasingly large part of the landscape surrounding us. And we wanted to use this trend as raw material. To start building something out of it.

S: The image becomes three-dimensional; you can bend it or twist it. There is certain poetry to it, and some very powerful symbolism. It is a cross between our interests and our previous life experiences ‒ mine, which is more image-related, and Nick’s, more involving material objects.

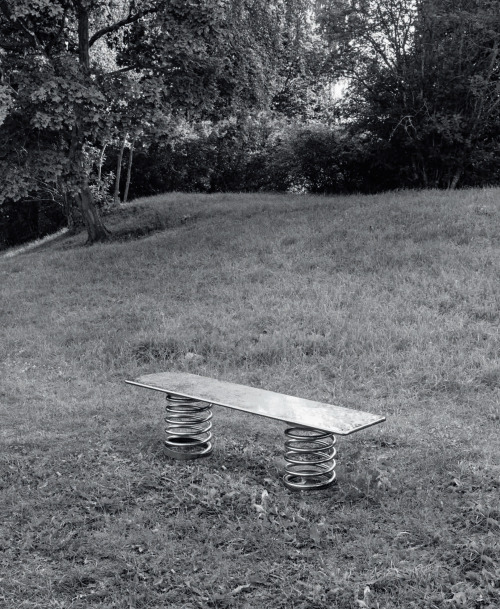

Superbench. Photo: Soft Baroque

I like that many of your works are, in some sense, futuristic and yet simultaneously also contain a sizeable dose of irony about the ‘futurisation’ of everything in the world. I totally loved your description of the Superbench, which, in keeping with the concept, does not feature either USB chargers or a WiFi hotspot: ‘Being super is being ideologically pure but somewhat irrational with an element of fantasy.’

S: I think that it is a good description of everything that we do. I do not recall the particular text anymore but the project was quite entertaining.

What do you think about elements of future in our reality? In which direction are they taking us?

N: I think that, more likely, we are reflecting in this sense about a not very distant and foreseeable future, reacting in our characteristic manner to what we see. We generally hate statements of the ‘this way is the right one, that way is the wrong one’ type. We don’t think that fake materials or plastic are necessarily wrong. The whole thing is so much more complex and complicated. Rather, we create certain areas where an observer may feel inclined to start questioning our visual culture, our object culture. At that, our objects are of limited edition; they are not mass produced, otherwise our responsibility would be completely different, we would think of them in a completely different way.

S: I agree with you. Of course, my personal view of the future is somewhat more pessimistic, but perhaps I should blame my Eastern European background for that. (Laughs.) In any case, in our joint projects we really do ask more questions than offer answers regarding the rightness or wrongness of this or that scenario.

N: It also has to do with style and aesthetics. Even at universities, they much more often talk about the functionality of objects, about the amount of time they will manage to save us, about what nature-friendly materials they are made of, than about the ways in which we view objects, in which we associate ourselves with objects in culture, why one object seems more valuable than another to us and what happens in our minds when we make this type of judgement. And it is not at all easy to make judgements about aesthetics and style, because everybody has their own opinion about that. These things are more difficult to recognise and analyse. But when people look at an art blog of some sort, that is exactly what they do pay attention to. They do not read descriptions, they decide at once that ‘this is cool and this is not’. We do live in a very visual world…

S: Our latest exhibition is, to some extent, a reaction to that sort of thing. To the fact that art projects appear in out field of vision as images, as pictures ‒ on Instagram or elsewhere. We try to move away from the flat image, to make it three-dimensional. And even after all that, most people still get their impression of what we have made via pictures, via images.

Fragment from exhibition World of Ulteriors at Etage Projects gallery in Copenhagen. Photo: Etage Projects

It is like an impenetrable wall.

S: Exactly, everything bounces back from it with the same kind of frustration. And we made an attempt to play on that in our show at the Copenhagen Etage Projects, the gallery that represents us. We thought about the fact, for instance, that when photos of whatever are published, they are placed against a grey or white background ‒ on which they have, essentially, zero context. They simply exist on this infinite background. And they are placed next to other things, which also exist on the same background, and it is, in a way, a whole universe of weightless images.

And that is why we asked an architect friend of ours to create some sort of ‘artificial environments’ for us. And we printed them in life-size. And arranged our objects on them. And it looked like rendering when you photographed them. So they did not even look like something real.

That is a sort of commentary on the whole situation. Why are we making objects if they become pictures, images anyway? We could have simply used rendering.

N: We take a white cube of an art gallery, furnish it with artificial 2-D interior on which we then exhibit our 3-D objects.

Exhibition World of Ulteriors at Etage Projects gallery in Copenhagen. Photo: Etage Projects

It looks like perceiving something as a material object is becoming a real luxury in our world. A luxury product. And so your works are a reaction not to the way we make things but to the way in which we think about them?

Probably both.

What projects are you busy with right now?

N: We are making a few things for the upcoming London Design Festival (the festival took place on September 16th and 17th – ed.), for an exhibition we are mounting with a few other people ‒ we will be showing masks. And some furniture as well. We are also showing a few of our things in Los Angeles; the opening was literally yesterday. Some other things are just in the development stage as yet…

S: There are a few more research-related projects as well. We were offered by a publisher from Milan to take part in a project on the subject of function/disfunction.

N: The publication, due for release later in the year, will be dedicated to the kind of knickknacks that are sold on the streets, sold to tourists. How these things are sold and who sells them. And which functions are more important for them ‒ do they have to appeal to children, does there necessarily be some kind of catch…

S: It also deals with the subject of forced (because of wars or politics) migration. And again an interesting link between two seemingly unrelated subjects: these weird cheesy little things made in China, and the life stories of the people who sell them.

N: And the whole thing is taking place on some sort of beach in Italy.

S: We are researching it, but we’re also thinking about creating some sort of object which we could also introduce into this ‘street market’ and then observe how this thing would survive in this world.

Could you tell about the masks you are making for the design festival? It is, after all, a very current thing: people increasingly often choose to redesign themselves not with the help of plastic surgery but with that sort of objects…

N: We are very interested in all sorts of cosmetic masks you put on your face like gel ‒ very weird objects. We would like to swap the liquid in them with some kind of more off-the-wall ingredient. That’s one idea. Another one has to do with an old sketch of ours ‒ a system that would transform a person into a fountain. It is a kind of hat with water running down the peak, and the water forms something like a veil in front of your face. Around the neck there is a receptacle that collects the water, and then a pump makes it go back again.

S: As if there were a waterfall in front of your face. We only have a sketch of this idea; we haven’t made the actual thing as yet. So that’s something we can try and do.

This presents so many opportunities and variations on the theme of recognition vs secrecy. Being open or hiding away. Being recognised not by your face but by your image.

S: These days, when the selfie culture is so ubiquitous, it is a very timely idea.

Saša Štucin and students at the summer design school MAD

In this case, my final question will be this one: if you were to make a mask for yourselves, what would it be like?

S: Yes, not an easy question; we have so many different ideas. Of course, I really like the waterfall. But when I was a student, my friends and I had this idea of a cloud-hat that would wrap you in some kind of mist when you put it on. So you’re walking, and this train of foggy cloudiness is trailing behind you. I find the idea of a human cloud very appealing; as a child, I used to draw people sitting on clouds a lot. I like it as a metaphor ‒ living on a cloud…

N: What I would make… Perhaps something like the lasers in laser pointers, for instance, and they would come out right from…

S: …the pores of the face? (Laughs.)

N: …around your face, so that no-one could see you. No-one could look at your face, or they would be blinded. (Laughs.) But that’s more like a weapon of attack, not a means of defence. Something like: ‘Don’t look at me, or I will start shining lasers at you!’

S: We will let you know what we did in the end…

It’s a deal!

P.S. As Arterritory.com found out, this Autumn was quite busy for Soft Baroque. “[For London Design Festival] we’ve made two armchairs and vase from aluminium (see below). Using a standard 40x80 mm aluminium box section we constructed a simple armchair. The anodised aluminium members, reminiscent of 2x4 timber, has sections graphically cut away revealing the hollow structure. It is a technical replica of a rustic primitive construction.

Regarding the mask. We started to work on the Waterfall cap, but we’ve ran out of time, so we will finish it for another show in January. We ended up presenting some sort of “pillow” mask. We also made some tests of trying to make glitter/shine Instagram filter in IRL mask version, but it will have to wait for another mask show:)» Stay tuned!