«This is a much more positive thing»

An interview with the well-known NFT collector Edgar Aronov from Estonia

‘All millennial collectors are investors. Many baby-boomer collectors bought art as a kind of indulgence; they were involved in a kind of art-washing. Millennials do not feel this need at all; they are not interested in washing anything off themselves; they just can’t be bothered. By investing, they support the project as a whole ‒ the team, the programming, the art. But only about 20% of people involved in this area belong to this category; the rest are no more than “tourists” brought in by a wave of hype. And there is, of course, an element of the luck of the draw to all this, just like to everything else crypto-related. Because the key rule in this area is ‒ never buy more, spend more than you are prepared to lose,’ I was told by Olga Temnikova who I called prior to my conversation with Edgar Aronov, an NFT collector and the person who teamed up with Olga and the artists represented by her gallery to launch the Mutagen NFT collection in early August; it took three hours to get sold out for approximately 1.4 million USD.

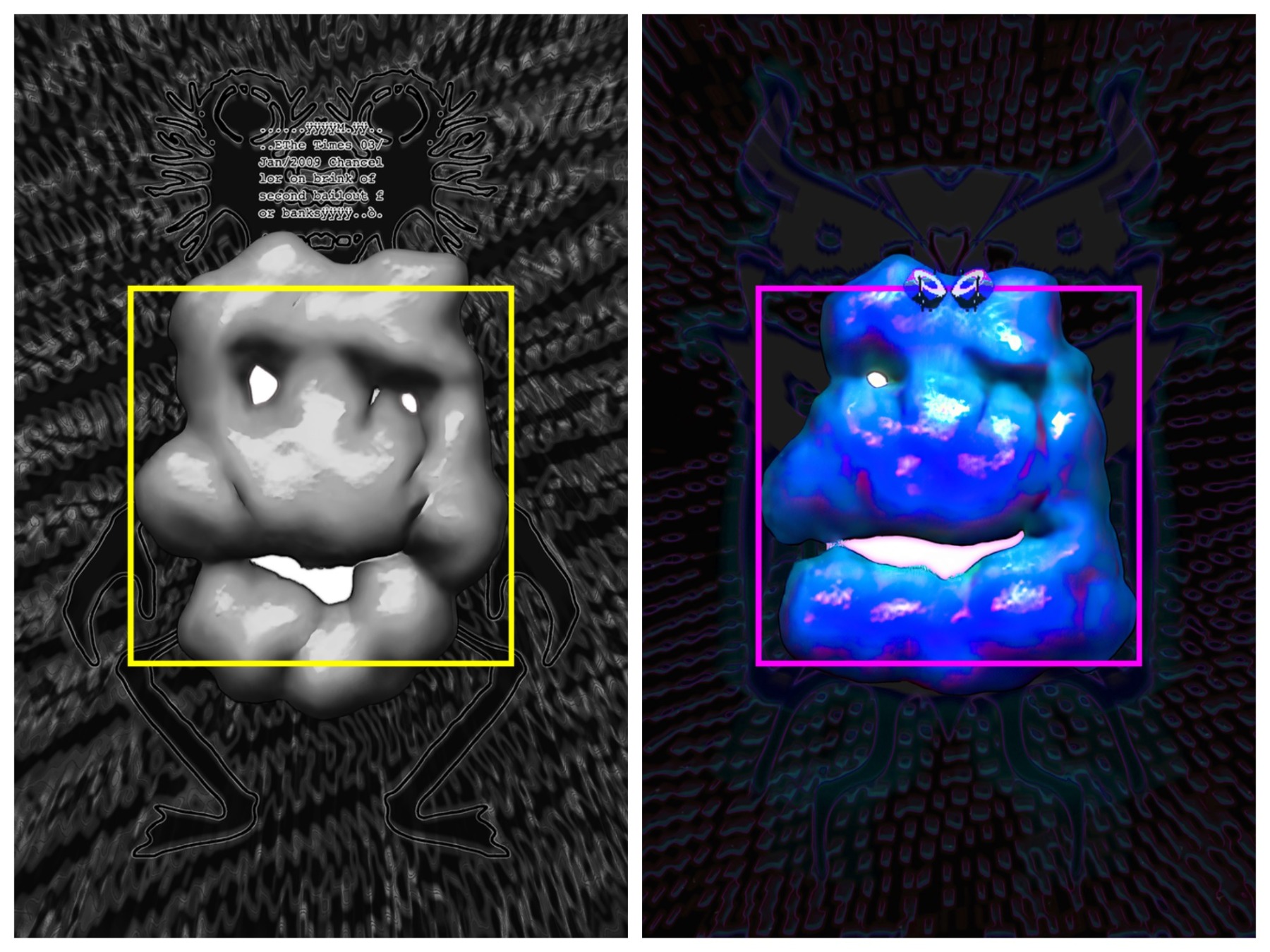

The collection was different from others constantly on offer in the NFT market in that the objects for it were created by institutionally recognised artists like Tommy Cash or Katja Novitskova, who were specially invited by the Temnikova & Kasela gallery to reflect on this trend in art and the art market.

Ilja Karilampi. ANTI-BURN MUTAGEN GOPNIK. From Mutagen collection

The general trend seems quite clear: first, NFT art transformed from fun for computer freaks into a genuine epicentre of hype involving huge sums of money; now this steadfastly and incredibly fast-evolving area has attracted the attention of traditional art institutions. To name but one example, an NFT art exhibition entitled ‘Etherial Aether’ is in the works at the St. Petersburg Hermitage Museum where it is being mounted by the prominent curator and contemporary art expert Dmitry Ozerkov.

Introducing the upcoming project, Ozerkov writes: ‘NFT positions itself both as a new type of existence for art and a new form of collecting. A non-fungible token (NFT) is not a work of art in the old analogue sense of the word but rather a digital copy of a file (in formats like photography, video, audio, etc.) which is stored as a digital accounting unit in a distributed blockchain ledger. The main idea of a token lies in the uniqueness of the code and the quality of non-fungibility, non-replaceability: proprietary information is its intrinsic value and can be transferred within the system by means of a smart contract, i.e., a computer control protocol. A token cannot be no one’s property: owning this art has become the essence of the art... Collecting has been undergoing change all the time. With the emergence of avant-garde and conceptualism, ownership of easel painting ‒ testimony to the artist’s mastery ‒ was replaced by owning an object, a conceptual symbol of the original idea behind it. And now, or so it seems, we are on the edge of a new stage: departure from the idea and focusing on the fact of ownership. The subjective ownership of a digital asset is more important than any objective qualities of said asset.’

At that, Dmitry Ozerkov (like many other experts from acclaimed art institutions) is of the opinion that the artistic quality of the main wave in the NFT art world is currently quite low and will inevitably grow ‘both on the level of external appeal and on the level of quest for philosophical profoundness in technology’.

Nik Kosmas. UNIVERSAL LESSON. From Mutagen collection

This is where it gets interesting. According to Olga Temnikova, those who actually really live in the NFT world are not particularly interested in the opinion of experts from the ‘big world’, the world of institutions and all sorts of top lists. And it is this approach that is the source of the appeal and freshness of this new ‘Wild West’. They judge success according to their own criteria. ‘What constitutes a successful NFT project? There are three aspects to it. Recognisability. Rarity. And community. They rely on constant communication at online forums and on Discord ‒ about what this or that is, what it actually means, who has been quick enough to buy what and who sold what for how much,’ says Olga. To make it in the NFT world, a mere formal involvement is basically not enough. And this is where the role of a ‘guide’ who can present a new collection – in a sense, serve as its warrantor – becomes crucially important.

For the Mutagen project, the role of this crypto-insider was taken on by Edgar Aronov. ‘He is an NFT collector himself, and that is exactly why we joined forces with him for this project,’ Olga explains. ‘He has the mentality of a collector – that kind of congenital trauma (laughs).’ Edgar has long been involved in digital business; his portfolio contains a number of large start-up projects, and he is by far not a newbie in the crypto-world. We contacted him on Google Meet, and Edgar occasionally shared with me the screen of his notebook and whatever it displayed at the moment to clarify or illustrate a certain point he was making.

Edgar Aronov

How long have you been actively involved in the start-up and digital business scene?

For about ten to twelve years now. The companies that I created were quite specific ones. The first one worked with the community of scientific research. We had this group of different researchers whom we hooked up with structures of various governments that were interested in supporting their work. The second one, which I am currently still involved with, was launched a year ago; it is called Eventornado and aimed at organizers of hackathons [from hacker + marathon, a forum for developers where specialists in various areas cooperate to solve a specific problem over a certain period of time ‒ Ed.]. We built this platform for them, which considerably simplifies the whole process.

I am also quite actively involved in the crypto scene as well and am gradually transitioning to full-time activity in this area. And that includes my interest in NFTs.

What are you focusing on in this area?

My focus is actually quite an extensive one. It covers financial apps and NFT, which has, of course, evolved into a very interesting phenomenon. Before the emergence of NFT, the majority of people in the crypto-world were geeks of a certain type; it was a very niche subject for people interested specifically in financial stuff, in cryptocurrency. Whereas these days, culture has also been added to this crypto-world and, thanks to NFT, people who previously didn’t know a thing about bitcoins and that kind of stuff have also been joining it in growing numbers. And there are lots of these newbies.

What is your own take on NFT? Is there an emotional engagement for you with this area?

Definitely. Initially, I never suspected I would get so carried away with the whole thing. I have bought quite a lot of NFTs and I don’t feel like selling; I do have a kind of emotional attachment to them. Besides, the actual NFT community is also very appealing; it is a completely different scene than the cryptocurrency circles where people with different ideas are constantly fighting each other. This is a much more positive thing.

What kind of NFTs do you personally collect?

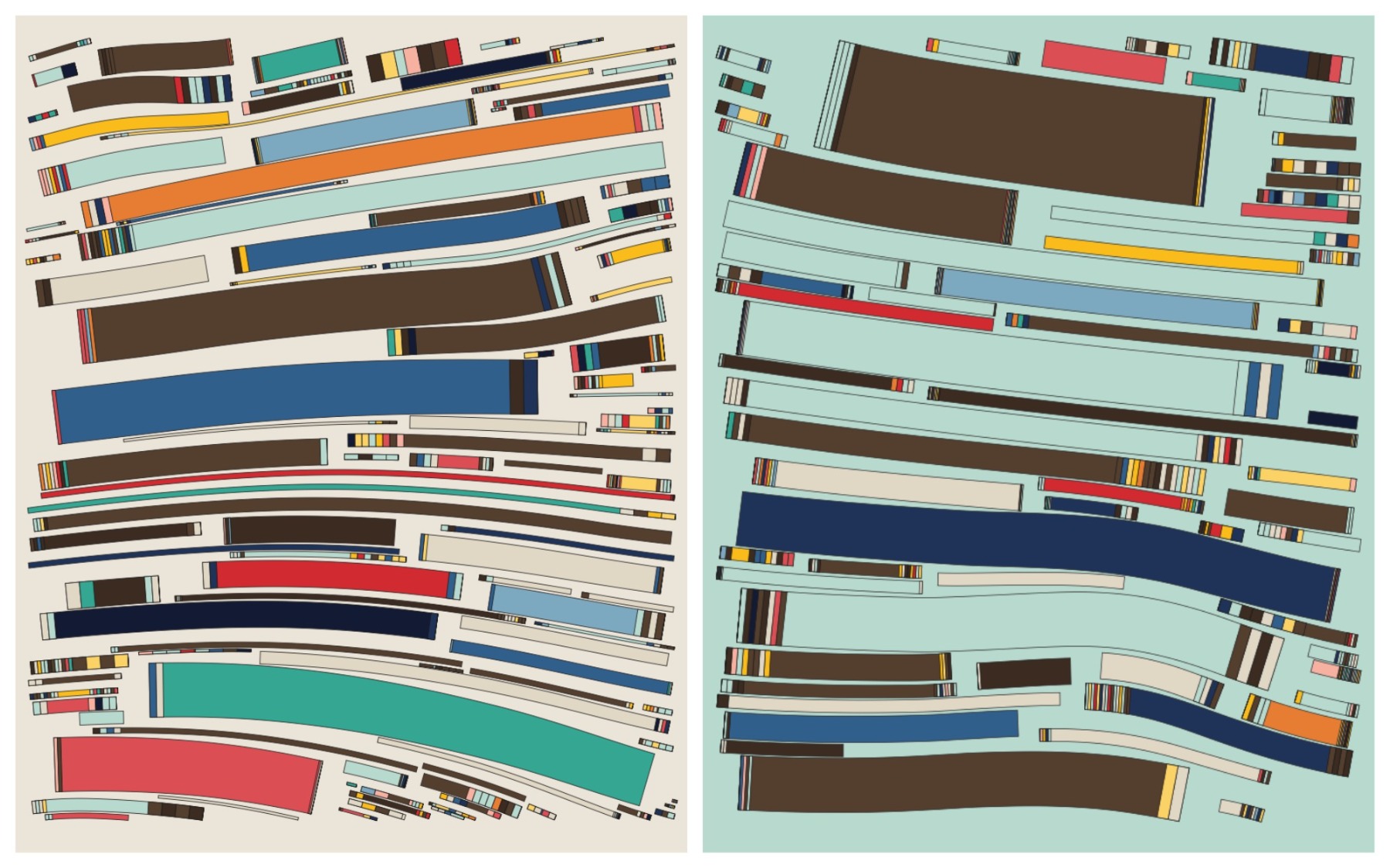

There are several types of NFT. Currently great popularity is enjoyed by generative art. It is not a new phenomenon per se: it is art that has been created with the help of a computer, of programming. However, with the rise of the crypto-era, its popularity has grown considerably. The idea is that the programmer and the artist (sometimes it is the same person) create a certain code and post it on Ethereum, into the computer environment that never ever stops, never comes to a halt. And once it has been stored there, nobody can change it, rewrite it or stop it ‒ not even the creator of the code. And collectors start minting using the code; the artist, in a way, hands over control over the appearance of his or her work. Collectors press the button that activates the code, and so the work of art, now essentially independent from the artist, is created. The artist can only imagine what the final version of their work is going to look like.

Project Fidenza, a signature work for the artist Tyler Hobbs, made its debut on the Art Blocks platform in June. Generated randomly according to an algorithm invented by Hobbs and jam-packed with vivid curves and multi-coloured blocks, the 999 works from this collection were offered for 0.17 ETH per piece (about 400 USD at the time). They are currently on sale in the OpenSea secondary market for up to 1000 ETH (approximately 3.5 million USD) per piece.

So the thing that NFT collectors are buying is not the code but these particular products of the code?

Yes!

And there can be as many variants of the ‘product’ as there are buyers?

Yes, approximately. Although the total number of variants is nevertheless limited. I’m going to show you something… Just a minute. Look, there is a very popular project called Fidenza on OpenSea. What we see now, these specific images ‒ it is what somebody has already minted; this already belongs to somebody. But this way we get to know the general style and set of elements, and we have an approximate idea of what we are going to get. To be honest, I’m not even sure why generative art is so popular. Perhaps it is exactly because here, for the first time in history, the artist transfers the control over the final appearance of their artwork to somebody else. And, once the code has been created, no one will be able to stop it.

Another type of NFT art is avatars, profile pictures. And there are always NFT collections consisting only of avatars on offer in the market; for instance, it could be some kind of animal pictures. I am not sure we can really call it art. But it is collectible stuff.

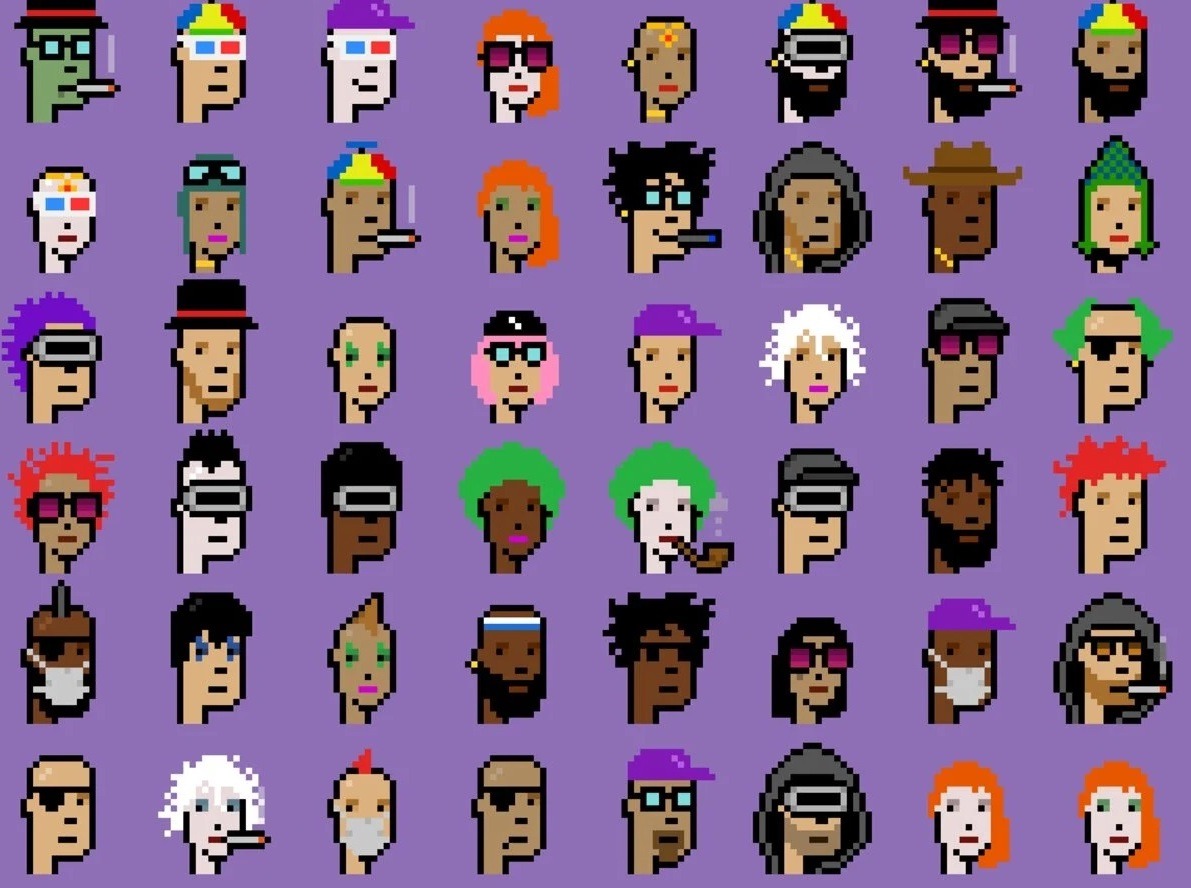

CryptoPunks were developed by Larva Labs, a team of two Canadian programmers, Matt Hall and John Watkinson. They became the first ever NFT community, a series of 10,000 pixel art images that first appeared in 2017. Later avatars from CryptoPunks became a kind of status symbol; individual images from the series were sold for millions of dollars. In a way, they showed the way for other NFT communities that followed.

Like Pokémon cards…

Exactly like that. Perhaps the greatest success story of this type is CryptoPunks. The prices for some of their images reached 7 million dollars.

Is that a group of artists behind this?

Yes. And their works recently went on sale at Christie’s. They were the NFT pioneers (as in they were earlier than 99.9% of NFT projects and they drove this trend the most), but technically they were not the first, since there were a few NFTs before them as well, but none of them became so popular. They appeared three or four years ago, before the current hype surrounding NFT. And that is why they have a kind of historic value in this area. These are, if you like, the Mona Lisas of the NFT world. Top historic value and top prices. The highest-sold work by Cryptopunks went for seven million dollars, which is the record so far.

CryptoPunks #9552

Уау!

But I still believe that about 95 % of the value is down to their historic importance. They were far from being that expensive no more than a year or two ago. These days, if you own an avatar from CryptoPunks, people regard you differently, with a considerably greater respect. So this is also a status-related story.

Another interesting project is Art Blocks, the main platform for generative NFT art. Artists can upload their collections here; there is also a specially curated section.

Normally, a single collection on offer contains several thousands of NFTs. They are all slightly different but have been created by the same system ‒ only with varying parameters.

I read that the NFT market has been changing recently ‒ collection prices have dropped. Not because the levels of activity have been low; quite the opposite, in fact ‒ more and more collections go on sale, activity is increasing but the prices are becoming more accessible, more democratic.

The focus has shifted a bit. The thing is, there is a built-in mechanism of royalties to the creators from each resale of the NFT ‒ between 2.5 and ten percent. Theoretically, the author ‒ the artist, the programmer ‒ can go on earning forever. These days, it makes more sense to offer a collection for a moderate price, so that everybody who wants it can buy something from it. And then, if the collection is a success and its value is increasing, you will earn much more in royalties.

And yet, compared with other NFT objects, NFT art is still a very expensive area with initial prices for the collections to the tune of several million dollars. And a successful collection is the work of not just an artist but also a programmer and a community manager; it involves proper marketing. In a way, it is even reminiscent of a start-up. Working with a collection is not just creating and selling; the value also must be maintained or increased afterwards. It means perpetual work with the community, communication, exchange of information and opinions. Without all that, a released collection will have no value at all.

The Meebits – new 3D collection by Larva Labs

Which means that if I am an artist, I definitely need a programmer who will develop a code for me...

Not necessarily; there are platforms that will do that for you. You upload your picture, and they will transfer it to Ethereum. And then you will be able to sell it. Basically, you can put either whole collections or individual pieces on the market.

Communication with the community, however, is a major thing. Occasionally you see a celebrity release their own NFT and no one buys it. The actual crypto-community is not that big; it is not that difficult to get in touch with it. When I’m asked about the best way to start doing it, I always tell people to get on Twitter, follow all the collectors there, contact them and promote your work. Twitter is what the majority of NFT collectors use to keep in touch.

Interestingly, this is reminiscent of the model of a traditional marketplace or a bazaar where the vendors are constantly communicating, praising their goods or simply doing banter. It seems like a typically human approach, actually…

Yes, and the human factor is generally very important here. Collectors buy because they know the person or group of persons behind the particular piece ‒ not just because they like it in a visually appealing sense. If you want to be in demand among these people, you must present yourself, your work, and prove that this community matters to you ‒ that you would like to stay part of it and go on creating new works in the future.

That’s interesting because I was under the impression that the crypto-world is a largely anonymous one, where everybody is hiding behind nicks or avatars.

You can, of course, remain anonymous.

So nobody cares who you are in the ‘real world’ and what matters is your role in the community?

Exactly!

Let’s take, for example, the Pulsquares’ [above: video from the pulsquares.art website ‒ Ed.] project of generative art, a very popular, very high-end collection and one of my favourites. It was created by an anonymous scientist from Brazil who has long been interested in fractals and complex systems. We don’t know who he is, we only know his handle. People tried to find out who stands behind this nick, but they failed. And that’s fine, it is perfectly alright in the crypto-world; the important thing here is ‒ what is your product? It is, however, much more difficult to start from scratch as an anonymous person: you must make a much greater effort to convince people that the thing that you are doing matters.

Regarding Pulsquares, the first collection was offered by its anonymous creator for free. It was a collection of 1000 NFTs. People took a closer look at the project and decided that this guy knew what he was doing. And so for the second collection, he could already ask a small sum of money…

Do you operate in the crypto-world under your real name or a nickname?

Yes, under my real name. I have often wondered whether I would not do better to switch to a completely anonymous status (laughs), but I am still operating under my own name.

Nik Kosmas. BODYHUNTER E02. From Mutagen collection

If I understand correctly, in terms of your collaboration with Olga Temnikova and the Mutagen project, it was specifically your duty to attach value to the collection in the eyes of the crypto-community?

Since I enjoy some level of popularity in these circles, it was easier for me to tell people about the collection and the idea behind it. Particularly collectors like myself.

Basically, there are two types of projects regarding their approach: some are highly technological ones with just programmers/software developers behind them. And then there are highly artistic projects without any special programming, simply converted into NFTs. What we wanted was to choose a middle way; we wanted to take some ‘traditional’ high-level artists and hook them up with top-level programmers and build a genuine top-quality collection. We offered 4096 NFTs of which 40 (named Genesis NFTs) mutate, each into 256 possible variations.

Who bought them?

Mostly individual collectors, but there were also groups of people.

Among other things, the project description contains information that ‘Mutagen coordinates randomness with fairness, in that the project revolves around a new value attribution model: an Expected Value Pool’. What exactly does this refer to?

The question is ‒ how do you plan to sell your collection ‒ is it a fixed price for each NFT object, or is the price going to change depending on the way the sales are unfolding? According to the model that used to be popular, the price grew whenever anyone bought NFTs from this collection. Which means that if I buy 20 NFTs from a collection and you make a purchase immediately after me, the same number of NFTs will cost you more. The price was artificially raised higher and higher. It is not a very efficient model; it’s based on FOMO (Fear of Missing Out). People think: ‘If I don’t buy immediately, it will cost me more, even ten minutes from now.’ The NFT community no longer sticks with this model and tries to avoid it. The most popular way of attributing value is fixed price. You are saying: This is my collection of 4000 NFTs; each NFT costs 200 dollars. And as long as it has not been sold out, anyone can purchase an NFT for said 200 dollars. Meanwhile, the expected value pool model is something quite different again. The thing is, there are works of varying degrees of rarity in every NFT collection. In our case, the price may change depending on the number of rare works still available. So let’s say there are 4000 NFTs, and someone goes and buys 500 of them. If these 500 were extremely rare and special ones, it means that the remaining value in the pool is lower now, because the rarest NFTs have already been sold out. And then the price drops for the next purchaser.

An important detail here is that there is no way for you to know what exactly you will get; it is like a lottery. When you are buying something from a collection that’s put into circulation, you have an approximate idea of how these pieces all look; which ones you are going to get is very much a matter of chance. And that is why many people rely on the luck of the draw; after all, if you are lucky enough to end up with a rare NFT, you can buy it for 300 dollars and sell it a month later for 100 thousand...if you are very lucky.

The element of rarity is very important here. As far as I understand, it is being deliberately programmed.

Yes, it is absolutely artificial. Let’s take the very simple and entertaining case of the Pudgy Penguins. They are proportionately divided into various types. Let’s take the skins; there is an option of gold skin. In all, there are 8 888 penguins, and the creators of the collection have decided to make 44 of them golden.

‘Pudgy Penguins is a collection of 8,888 randomly generated Pudgy Penguin NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain. The 8888 Pudgy Penguins create our community known as The Huddle. Our penguins are pudgy, cute, fun, and a little goofy. Pudgy Penguins are known for eating too many fish and creating legendary memes,’ informs the pudgypenguins.io website. Pictured: Pudgy Penguin #6834

It's just so… you know, so obvious, like: they are golden so they must be more expensive!

Yes! (Laughs) And so people think ‒ there are just 44 of them! A rarity! Besides, the gold ones also look cuter.

It is, of course, a very simple example. Things can be so much more complicated with artwork of another level. It gains particular importance in the secondary market, when people already see what they are buying, whereas at the time when a collection has just been released, people get their penguins randomly.

What are your thoughts on the artists involved in the Mutagen project – did you select them with Olga or was it perhaps her part of the project and you did not interfere with her decisions?

Yes, it was mainly her area of expertise. I am still only getting to know the conventional art world and, prior to meeting Olga, I could not navigate it very well. She dealt with the artistic side of the project; my job was to introduce the artists’ work into the world of NFT ‒ find a developer and put it into market. Finding a very strong developer can be crucial for the NFT project. In our case, we were lucky enough to have Hendrik Kaju as our lead developer who took care of everything technical.

Katja Novitskova. PDB MUTANT 01 & PDB MUTANT 06. From Mutagen collection

Are you satisfied with the result?

Yes, I am satisfied because some quite influential and active collectors bought from us. But there is still lots of work ahead for us. We must promote the project, the collection that has been created and sold out, to maintain its value. But we are also considering creating new collections in the future.

That means that, unlike the conventional art market, you must still carry on taking care of art that has already been sold?

Yes, not just take care of it but do it in public so that others can see that you are taking care of your collection, you are still taking responsibility for it. If you create a collection and then leave on a six-month vacation, it may quite possibly quietly ‘give up the ghost’. (Laughs)

It is a very creative and exciting world. But many people also speak about the fact that it is not a very environmentally friendly one ‒ that mining and transforming objects into NFTs demands electricity that is produced by burning gas or coal.

There is a bit of truth and a bit of myth in it. The media love making a big deal of it in headlines. Yes, Ethereum needs huge amounts of resources, that much is true. But NFT does not. People think that if you create NFTs on the Ethereum platform, you automatically produce an even bigger burst of ‘exhaust’. But it does not work like that. In practice, you do not spend even more resources when you create NFT. Because how does Ethereum work? It is a blockchain that produces a new block every ten seconds, and every time someone does something with Ethereum, the data are encrypted into this block. The block can contain hundreds or thousands of NFTs or no NFTs at all. It is of no importance. It does not matter how much information will be encrypted into each individual block; a new one will still be produced every ten seconds. And so the statement that each newly produced NFT means additional spending of resources is simply not true. Whereas the statement that Ethereum per se consumes resources is true. But it will gradually depart from this situation. In a couple of months, an Ethereum update is expected, and it will remove this bug. Next year will see it become approximately a thousand times more energy efficient.

Tommy Cash. GOLDEN. From Mutagen collection

What are your thoughts ‒ can we come up with a forecast for the next ten years or so? What is going to happen with the value of these collections?

The problem is that there are so many new entries that, as likely as not, the majority of these projects will not be able to retain their value. And yet some of the projects, like CryptoPunks, are probably not just going to retain their value but even gain more ‘weight’. Because it is historically important stuff. Basically, those projects that are already recognised as historically significant today will still do very well. But many others will reach zero value. The mood is euphoric right now; loads of new projects emerge and people buy stuff without having a very clear idea about it. And the odds are that it will not even take ten years, that in just three or four years many projects will have lost their value.

Perhaps that is exactly why it is important to involve artists with a name and reputation in this game?

It definitely helps, yes. But generally, when thinking of which projects will survive and come out as winners, it is the ones that will continue working on their significance, continue communicating with the community and go on producing new works. There is no stopping in this game.

Well then, we are currently witnessing a certain boom and we shall see what will be left of it in a mere three to four years’ time...

Yes. It is quite possible that there are some items among the NFTs in my collection whose value will significantly drop. But you can never know that for sure. It is very much like investing in new tech companies. You place your ‘bets’, you buy what you like, and you hope that others will like it, too. And that the creators will continue their work. But in reality, you can never be a hundred percent sure of that.

Thank you! You helped me make sense of the picture. All the best with your NFTs!

Thank you!

Edgar Aronov’s avatar from the CryptoPunks collection