When Contemporary Art Flirts with Anthropology...

Francisco Martínez

26/04/2016

Is there a common ground between contemporary art and anthropology? And what can we learn from each other? This article invites the reader to think about art and anthropology simultaneously through reviewing four exhibitions recently organised in Estonia. Obviously, there are similarities and differences: art is a practice – open-ended, using adaptive methods and visual representations, whilst anthropology is an academic discipline that relies on concepts and fieldwork to explore the human condition across time and space.

However, artists and anthropologists are increasingly working across the boundaries of their respective disciplines to explore the generative potential of each other’s methods for engaging with communities and disseminating knowledge. For instance, when art practice is turned into research, social ambiguities are made visible in a more direct and appealing way. Also, the combination of ethnography and contemporary art makes it possible to not only depict real evens and situations, but also do it in a way that the representation itself becomes a social fact.

Jaanus Samma. “Not Suitable for Work. A Chairman’s Tale” (archive photos). Photo: Reimo-Vosa-Tangsoo. Courtesy of the artist

An example of all this is Jaanus Samma’s exhibition “Not Suitable for Work. A Chairman’s Tale”, which tells the story of Juhan Ojaste (the Estonian pavilion at the 56th Biennale di Venezia; now held at the Museum of Occupations). Samma uses the biography of Juhan Ojaste aka the Chairman to demonstrate what it meant to be gay in Soviet Estonia.

Juhan Ojaste was born in 1921 in an Estonian village, made it through the war, married, worked on a collective farm (колхо́з – kolkhoz) and eventually became its chairman. Everything was fine until the early 1960s, when he was arrested for same-sex relations and an abrupt social downfall occurred: “Then he was sentenced to a year and a half and was released from prison totally broken. There was no question of continuing as the chairman of the farm. His wife abandoned him. His dignity was crushed”, Samma contextualises.

Regardless of the tragic life of the Chairman, Samma avoids portraying him simply as a heroic figure. Instead, the artist opts for exploring the genealogy of homosexuality in Estonia without descending into the rhetoric of victimisation or vindication. In 2011, Samma began to investigate micro-histories in archives and conduct interviews with elderly gay men about their everyday life. As he recalls, they told him many interesting stories about characters with such nicknames as the Butterfly, the Balloon, the President and the Seal.

Elegantly and with self-irony, Samma manages to represent a controversial matter in a caustic way, making visible the non-verbal aspects of social exclusion. It is in this sense that the exhibition resonates with actual anthropological debates on migration, gender inequality, gay rights, identity-making and ways in which societies accommodate differences overall. The artist has previously used urban ethnography as a trigger to organise an exhibition. For the show “Hair Sucks Sweater Shop” (2015), Samma gathered obscene graffiti connected to the topic of sexuality and queerness from different European cities, reflecting on his own subjective experience of the urban space as he explains.

Asked to reflect on the topic of this article, Samma replies:

“I don’t think about my practice in anthropological terms per se, but I agree that there’s definitely a convergence in methodology. I see my practice as research-based art – specifically the projects I’ve dealt with urban space and gay history. And this is the reason why I like doing art – to have the ability to choose my tools from different discourses and disciplines (history, anthropology, conceptual art...) and not limit myself just to one”.

In a bricoleur way, artists and curators usually use the different tools and methods available to communicate their way of viewing the world to the audience. This is related, for instance, to the field of material culture studies which investigates how we know and do things, as well as how objects are tangled up with our memories. The concept of material culture originally emerged from museological, archaeological and anthropological works in the late nineteenth century.

An example of the indexing character of our material engagements is Georg Simmel’s socio-aesthetics, according to which material forms become experience not only as an external world, but also as mental life. Siegfried Kracauer picked up on this idea to remark that surfaces and ornaments are not superficial but rather an assemblage concentrating the phenomena of everyday life. We can also refer to Walter Benjamin’s “Arcades Project”, which examined the secondary, the excluded, arguing that by displacing the angle of vision, we make something different from what was previously signified emerge.

The Chimera. Photo: Kristiina Hansen

All these ideas were exemplified in Kaire Rannik and Liina Siib’s exhibition “The Chimera” (Draakoni Gallery, February 2016). The show contrasts how objects look like in reality with how they appear in our subjective world. The ‘objects’ included in “The Chimera” challenge any clear-cut distinction between artwork and document; they are rather displayed as thought-images that oscillate between irony, analogy and allegory, pondering over the borders of plausibility and implausibility.

The effect produced by the show is therefore one of estrangement, a process of interruption that dislocates the visitor. Viktor Shklovsky defined estrangement or defamiliarization (остранение - ostraneniye) as a form of world-wonder that leads to an acute and heightened perception of the world. As Svetlana Boym (2005) elaborated later on, the idea is to force people to see common things in an unfamiliar way for the sake of the world’s renewal. Other equivalents of estrangement could be found in Bertolt Brecht’s strategies to prevent an alienation effect by creating discomfort (Verfremdungseffekt), or in Theodor Adorno’s shudder, shaking and shock (Erschütterung) that reminded of the artificiality of the social.

Reflecting on her work methods, Siib comments:

“First I collect information and use it to re-stage representations. So I use anthropological methods as a way of contrasting categories and leave behind stereotypes. I also do fieldwork, but in art practice we are freer in our inquiries; for instance, we don’t have to be accountable or politically correct, and we can explore creative storytelling... As an example, nowadays I’m involved in a project researching Estonian women working in Helsinki, and when I first met with these women I had to revaluate all my initial ideas, as if I were an anthropologist testing a different hypothesis”.

Siib participated in a round table conference about art and anthropology organised at the EKA gallery for the finissage of the exhibition “Place Oddity” (February 2016). The show, curated by Lilli-Krõõt Repnau and myself, drew attention to those places that produce a limbo or liminal condition, like passages into a heightened state of consciousness. These odd places were described as ‘the corners of life, those eerie zones which create a sense of being in-between... invite retrospection, address alternative orders and facilitate critical distancing”.

One of the artworks included in our show was Flo Kasearu’s “Basic Navigation in Chisinau” (2014), which contraposes the spatial memories of pedestrians in the Moldavian capital with the representations of street maps. As Kasearu explained at the round table event:

“Anthropology appears to me too serious, or too realistic. In my works, I try to be more playful and explore different sorts of storytelling. For instance, in “Basic Navigation in Chisinau” I act as a total stranger, as if I had just landed there aboard an UFO. Another example is the performance “House Music’ in front of the Flo Kasearu Museum with Riina Maidre, for which we investigated the everyday rhythms and poetry of the Pelgulinn neighbourhood with the help of the Facebook community.”

Art-making is integral to social relationships; there is also a connection between aesthetics and morality, between the way in which we perceive the world and want to make it up. This assumption is akin to the way public anthropology addresses actual social problems beyond disciplinary boundaries, resisting the separation of theory from application and engaging audiences in a more interactive way.

Works by the inmates of the Tallinn prison. Photo: Lilli-Krõõt Repnau

Among the artworks that formed the “Place Oddity” exhibition, we included paintings, drawings, maps and board games created by inmates of the Tallinn prison. For 19 years, the prison official Aljona Toporkova has been archiving the works of art produced behind bars, also recording memories of the process and the context of their creation:

“A prisoner tried to draw this painting for a very long time. At the beginning, the background was white and the man in the picture appeared to have hazy eyes. Then the prisoner changed the background to black and only dealt with the picture when he was in a bad mood. But one day, the inmate came to the art class, cut out some paper butterflies, glued them on and announced that the painting was finally ready.”

The range of the exhibited works varies from deeply personal narratives of isolation to forgiveness, addiction, criminal inclination or solidarity with other inmates. The stories accompanying these paintings and drawings help understand the emotional engagement of the inmates, the ongoing process of self-reflexivity and the existence of something like ‘the culture of incarceration’.

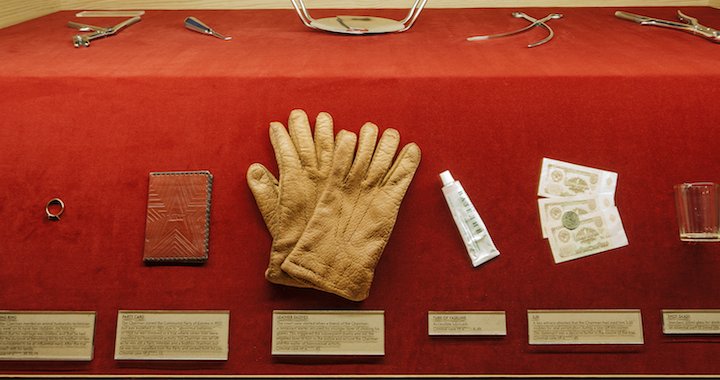

Conducting fieldwork ‘as conceptual art’ has been defined by Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov as ‘ethnographic conceptualism’, a form of public engagement that turns the space of an exhibition into an open site for anthropological inquiries. As in the case of his exhibition “Gifts to the Soviet Leaders’ (2006, curated with Olga Sosnina at the Kremlin Museum), shows can be used as research tools, for instance, by studying the range of reactions provoked in the visitors.

Professor of anthropology Patrick Laviolette also argued for the cultivation of new forms of knowledge during our round table event:

“The combination of art practices and representations with anthropological methods not only do not reduce the rigour or validity of the research, but also enhances it by allowing us to involve informants on a different level... In terms of the difference of an anthropologist becoming an artist and vice-versa, I do not think it is that easy. The main similarity might be collecting material and ideas about a given inquiry or matter, the study of social interactions... but in anthropology there is a theoretical aspiration and art practice might be more focused on the media of representation... but I also consider anthropology a creative practice because the writing, the dissemination of knowledge can be playful, too”.

Aesthetics of Amalgamation in Tbilisi. Photo: Francisco Martínez

My last example of a project engaging the ethnographic and artistic practices in a mutual dialogue is the exhibition “Aesthetics of Repair in Contemporary Georgia” (Tartmus, March-May 2016) that I organised with curator Marika Agu. By making use of terms such as ‘khaltura’ (botchery), ‘evroremont’ (‘redecoration in the European style’), ‘amalgamation’ and ‘scrappiness’, we have aimed at presenting the radical processes of construction and deconstruction in which the Georgian society is immersed, depicting, in a kaleidoscopic way, what has been left after twenty-five years of criss-crossing transitions.

Sophia Tabatadze, “Pirimze”. Photo: Johan Huimerind

As Agu explained during the artists’ talk after the opening of the show, once in Tbilisi, we first used ethnographic methods, did archival research and met with artists and gallerists; then we outlined the concept of the exhibition. For instance, we found in Georgia a wide gap between the human desire to improve a given situation and the suffering caused by not being able to do so. This compelled us to reflect on micro-works of adaptation and a sense of distributed creativity, namely, the way that people make use of what is around in order to cope with abrupt social changes.

An example of that is “Pirimze” (2015), a work by Sophia Tabatadze, which provides an insight into the culture of repair in Tbilisi. For decades, the central Pirimze building served anyone with anything broken: shoes, clothes, watches, jewellery, electronic devices, etc. The artist’s work comprises a documentary, a book and an installation – a replica of the handworker’s booth in Pirimze with the original tools and accessories. Sadly for many, in 2007 the old modernist building was replaced with a new “Pirimze Plaza” which now houses standardized, anonymous office-spaces that are unaffordable for the previous tenants.

Bouillon’s performance. Photo: Johan Huimerind

We can also refer to the scatological performance of Group Bouillon: all six members cut each-other’s hair during the opening – not only as an act of solidarity, but also as a way to get rid of bad energy, start from scratch and escape from civil pessimism. Full of tension and visually powerful, this act helped the audience to understand basic aspects of human condition such as rituals, the abject, sacrifice, dispossession and despair.

Overall, the combination of practices and methodologies allowed us to create a different form of engagement within the local context. As we conclude in the book accompanying the exhibition, the Georgian society appears to be made of contrasts and ill-organized forays of improvement, trapped in a never-ending process of renovation, which has created, in turn, some specific frames of perception.

By exploring the synergies with contemporary art, anthropology is furnished with new ways of seeing and experimentation. For instance, ethnography as a conceptual art depicts a moment that marks a change in a society, turning anthropology into a more proactive discipline. Foremost, art practices might convey knowledge about certain things in life in a better way than academic methods. After all, knowledge is conditional upon perception, in an aesthetic sense. Accordingly, arts-based research can also be a legitimate means of knowledge construction.

David Mindiashvili’s works are also an example of material culture. Photo: Johan Huimerind

As more and more scholars are willing to explore interdisciplinary methodologies, it is convenient to start discussing the next step – which is exploring cross-boundary ways to gather material evidence and communicate findings. However, the challenge is putting both the methods of anthropological research and art practice in service of an overriding question.

Coda: in my case, I started to collaborate with artists and curators because of the level and amount of art events taking place in Estonia nowadays. For me, anthropology is first of all an experiment that you conduct on yourself, testing how can you cross social and experiential borders and through that get some understanding about people who live in different circumstances; so it is an exercise of testing our own capacity to the limits – existentially and ethnographically, learning from the people around us and also fabricating situations.