The wound that needs healing

Maria Helen Känd

On the “Life in Decline” exhibition at the Estonian Mining Museum

In addition to the year-around underground program, the Estonian Mining Museum in eastern Estonia is hosting a contemporary art exhibition this year. The curator, Francisco Martinez, invited ten local artists whose conceptual work intervenes and engages with the already existing historical exhibition. The overwhelming majority of the artists have a Russian-Estonian background because this is the region in which most of Estonia’s Russian-speaking communities live.

A work by Anne Rudanovski

At a time when we are witnessing the depopulation and depletion of eastern Estonia (Ida-Virumaa), where the former major economy unit – the oil shale industry – is slowly diminishing and local social problems are being exacerbated by the termination of the factories, albeit for justified environmental reasons, we must get used to the ever-changing circumstances. The fragile conflict of these conditions is beautifully summarized in the exhibition’s poetical title, “Kohanemine kahanemisega”, which in Russian is “Во время упадка”, and in English, “Life in Decline”.

Eléonore de Montesquiou, Eksperiment Katja

Martínez, who has a PhD in cultural anthropology, focuses his academic and creative work on the study of East-European cultural heritage, political problems, and vulnerable communities, formulating his views concretely and fluently in the introductory text of the exhibition. Martínez writes: “Ida-Virumaa stands as a living laboratory where Estonia’s future is at stake, answering key issues such as the sustainable use of natural resources, social integration, rural-urban cleavage, and the maintenance of infrastructures”. Thus, he sees this region not as a place of disposability and destruction, but of opportunities. However, in what way do the works of contemporary artists mediate these problems and possibilities?

A work of Anna Škondenko

Entering the exhibition, I read the former mine employees’ stories about their lives in Soviet Estonia in the 1950s. Amazed and startled by their circumstances of living, I peek into the following rooms, where, in addition to the repository, the works of renowned Estonian artist Jevgeni Zolotko can also be found.

A work of Jevgeni Zolotko

Zolotko's works are often large-scale but minimalist installations. This time he intervenes in the historical exhibition with delicate iconostasis-like black and white compositions that involve photographs, symbols and text about the residents of Viivikonna. At the same time, the text can also be heard as oral narration floating throughout the room. Viivikonna is a village where during the 1970s, over two thousand inhabitants lived, but nowadays, one can barely see a few dozen people there. Ironically, the etymology behind the name of the village indicates impermanence and temporality – viiv means “for a short while” in Estonian, and konna is a term for a settlement. The stories shared by the locals of Viivikonna are deeply moving, and thanks to Zolotko’s contribution, the pain and beauty can walk hand in hand. Insofar as Zolotko is triggered by intergenerational relationships, memories, and interpretations of the past, his work is one of the most convincing interweavings of contemporary formal language and robust historical reality.

Darja Popolitova’s installation'. Detail

Darja Popolitova’s installation – in which she combines different media such as jewelry, sculpture, and video – awaits in the second building of the museum. Popolitova is an emerging artist from Sillamäe (also eastern Estonia) and is preparing to receive a doctorate from the Estonian Academy of Arts. To amplify the charm and sociopolitical force of her accessories, Popolitova often takes on the role of a fictional character in her videos – that of the Witch Seraphita. The installation, which concerns language policy and communication between nationalities, contains a great deal of irony and exaggeration, but makes one of the sharpest political statements in the exhibition. At the same time, the installation-like ensemble synthesizes with the rustical space and the outer mining area, where larger-scale jewelry pieces reminiscent of the glory times of the past – such as old pipes and wagons – can be found.

A work by the artistic duo Varvara&Mar

Outdoors, a red lifeguard tower by the pond attracts the visitor’s attention. This is a work by the artistic duo Varvara&Mar. Their playful yet socially critical installation consists of an almost sinking lifebuoy and lifeguard tower by the pond, covered with slogans and statistical data about eastern Estonia’s economy – a reference to the governmental rescue plans for Ida-Virumaa coordinated by the authorities from top to bottom, but which do not directly help on a human level the people who are stuck between the changing of regimes. In the first 30 years since the restoration of independence in 1991, Estonia has had governments with economically ultra-liberal policies that did not include a graduated tax system; this has brought financial growth but also enormous social inequalities, resulting in a large gap between the rich and the poor – the so called “second and third Estonia”, terms that emerged in the early 2000s as the first decade of cowboy-capitalism came to a close. Accordingly, perhaps the next fitting exhibit location for this installation could be the pond next to the government building Toompea, in the Old Town of Tallinn...

Sandra Kosorotova’s installation “Sore"

These are just a few examples of how contemporary art questions and amplifies the socio-historical reality in the Mining Museum. However, by synthesising art with artefacts, it’s also crucial to keep a balance so that the artworks don’t dissolve into the already existing space. Sandra Kosorotova’s installation “Sore”, made of beautiful minimalist weed-dyed textiles and transplanted weeds, carries a personal and a strong conceptual message, since Russian-Estonians often experience themselves as an unwanted “weed”. Yet the plants must have had either too much sun or rain, because they weren’t that easy to find and recognize without the booklet. Anna Škondenko’s idea of depriving her attic-like installation space of light played interestingly with the Jungian idea of the shadow side of the collective psyche, but the paintings themselves weren’t really easily accessible – neither visibly nor message-wise.

Laura Kuusk’s site-specific photography

However, a curator can never fully predict how the artists will formulate the discussed ideas. “Life in Decline” is, therefore, a convincing experiment and a nice synthesis between historical findings and the thoughts of the artists and the curator, and is worth experiencing. It may not contain as much hope and transformation as promised in the introductory text, but it is affecting in a poetic and even humorous sense – as in Laura Kuusk’s site-specific photography on the ongoing and changing challenges faced by Ida-Virumaa.

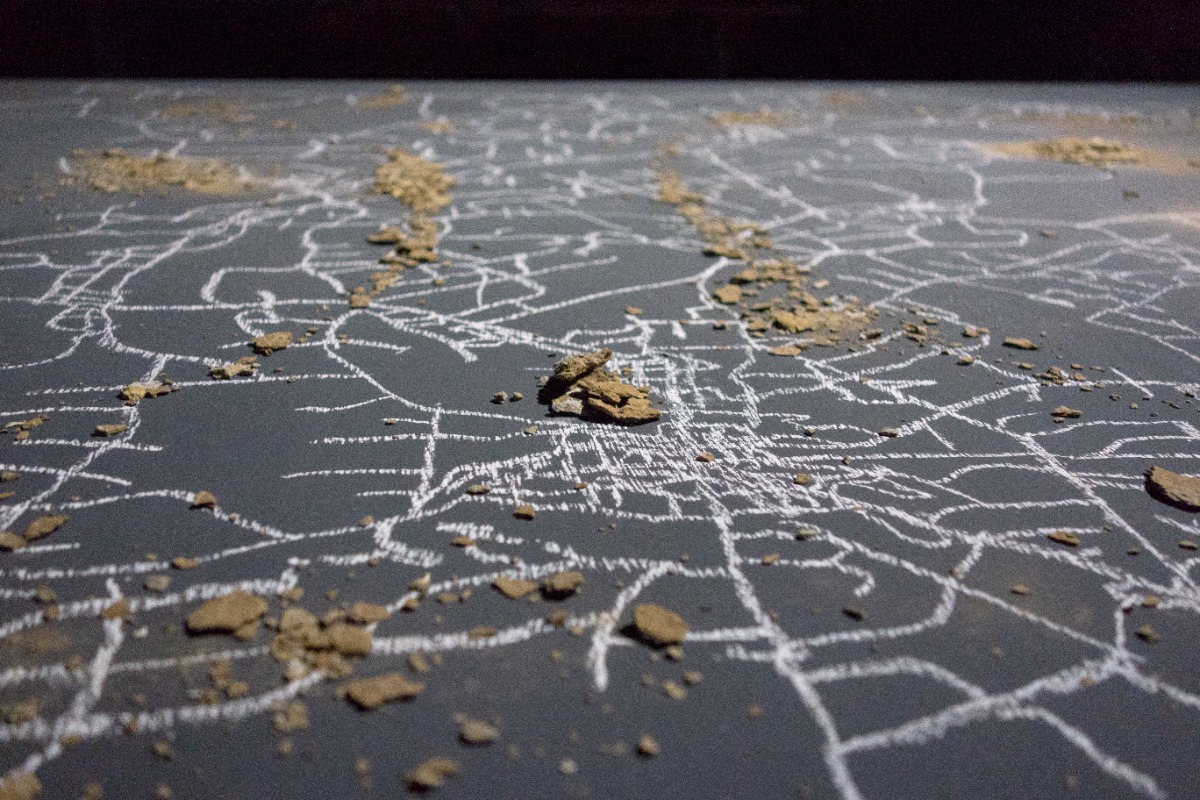

Geofractions by John Grzinich

If the only way to survive the first years of the Soviet occupation of Estonia in the late 1940s was to stick together and share what one had, then now we have witnessed that the more opportunities there are, the easier it is to abandon the people and places around you. There is a famous song from the time of the restoration of independence and the Singing Revolution period titled “No land is alone” / “Ei ole üksi ükski maa”, which narrates the story of uniting Estonia’s different counties for a greater good – against the environmental disaster planned by the Soviet government to start mining phosphorite in Virumaa as well as for the fight for independence. The song goes: “When in Virumaa all streams with clear water stay clean, only then do I have the courage to say that I live in my own land. I don’t want to, I can’t leave you, Virumaa!” In the wake of the EU agenda “Fit for 55”, the exhibition dwells on the burning social and environmental questions that concern the region – as well as the wound in Estonia’s social fabric that needs healing.

Edith Karlson, Another short story

Artists: Anna Shkodenko, Anne Rudanovski, Darja Popolitova, Edith Karlson, Eléonore de Montesquiou, Jevgeni Zolotko, John Grzinich, Laura Kuusk, Sandra Kosorotova, Varvara & Mar