Fractured signs of belonging

On the 13th Baltic Triennial ‘Give Up The Ghost’

21/09/2018

In marking the centenaries of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, a myriad of cultural and artistic projects that more or less centre on national and/or global identity have already taken place, and many are still yet to come. In an anniversary year of such note, this fact is both symbolic and self-explanatory: the defining of identity, or the search for this identity, leads us to not only look back at what has been accomplished, but also encourages us to ascertain what we ourselves have achieved up to this point and what is still left on the to-do list. Consciously or not, these kinds of concepts link together politics, economics and science, contemporary art, and both national and traditional cultural heritages. Consequently, attention is brought to trends of worldly importance and to personal identities on both a national and utterly personal scale. This subject of study, which has already been expounded upon in several recent exhibitions, has also become the crux of one of the most prominent contemporary art events in the Baltic States – the Baltic Triennial (BT). Compared to other years, with its thirteenth iteration BT is trying out a new approach by taking place consecutively in all three Baltic capitals. In speaking with Zane Onckule, programme director for kim? Contemporary Art Centre, she readily admitted that this solution was influenced by the three countries’ centenaries. BT13 opened at the start of May in Vilnius, at the end of June it opened in Tallinn, and now, on September 21, the triennial’s final phase will open at the kim? Contemporary Art Centre in Riga.

,%202014_jpg.jpg)

Pierre Hyughe. Untitled (Human Mask), 2014

This year’s Triennial is being introduced to the public with the title Give Up The Ghost, the overall objective being interpreting the notions of belonging and identity. The artistic director of the project is Vincent Honoré; he has been part of curatorial groups at Palais de Tokyo and Tate Modern, has worked with numerous world-famous artists, and since October 2017 is a senior curator at London’s Hayward Gallery. As already mentioned, this is a very important year for the Baltic Triennial because, for the first time in its history, the exhibition is being divided into three grand chapters, with each one having its own distinct assignment or thematic sphere. At Vilnius’ Contemporary Art Centre (CAC), emphasis was placed on ‘territorial and social body’ solutions as executed through art; the BT exhibition at Tallinn Art Hall (Kunstihoone) in Estonia reflected on sensuality and intimacy as parameters of belonging; and the Riga chapter of BT is dedicated to ‘questions of social norms, relations and structures, while also considering the notion of ghosting and fading away in relation to the large-scale exhibition format itself.’1 The core of the exhibition has been formed so that three seemingly different (and perhaps even unconnected?) chapters consciously share the same concern: ‘What does it mean to belong at a time of fractured identities?’

Sandra Jogeva. Feminist Crisis of Identity. Version 2, 2018

Caroline Achaintre. Got-o-Rama, 2016

At the beginning of this summer, in my interview with Honoré titled Never give up, I wrote that in philosophy, the term ‘fractured identity’ is defined as having many parts to one’s personality. The creative team behind BT13 have chosen not to link the concept of the project to this clinical definition but rather to the historical interconnections between fractured identities and the Baltic Triennial. The curators have, up to a point, highlighted not only the peculiarities characteristic to the relevant region, but also the roots of the emergence of these trends – namely, the restrictive conditions of the last century under which the national and contemporary art of each nation originated and then developed over the years. As Honoré has accented himself: ‘Taking into account the history of the Baltic States – especially the long-held view of these nations as being confined by their location between Europe and Russia, and therefore labeled with a sense of instability and a kind of shapelessness – it became clear that the question of belonging is a relevant concept through which one can think of the Triennial and its relationship to the region, as well as its meaning in broader discourses on global and contemporary art.’ I’m assuming that Mr. Honoré has not limited himself to the currently very popular task of analysing the geopolitical situation of the Baltic States, but has also looked at the behind-the-scenes of how the Triennial came to be – way back in 1979, to be precise, when the first iteration of BT saw the light of day (at that time still known as The Baltic Triennial of Young Contemporary Art in Lithuania2). Back then, in defiance of the ruling totalitarian regime, the new generation of artists expressed themselves in a critical and nonconforming manner, courageously presenting their ideas on local political and social conditions. Is that what created a basis for thinking about the fracturing of a society and then interpreting it through art? I’d say that’s rather doubtful. Nevertheless, this noting of the past, as well as the fact that, for a long time afterwards, most Baltic artists still balanced themselves between Western art perceptions and officially sanctioned art (throughout the 1980s and 90s) – is true validation of having the ambiguous feeling of belonging to this region.

Elīna Lutce. Corpus

Korakrit Arunanondchai. With history in a room filled people with funny names 4. 2017

The English expression in the title – give up the ghost – means ‘to die’, which could lead one to expect a rather sad mood emanating from the compiled exhibitions. Yet the creators of the exhibitions have cleverly played the theme by giving the notion a new utilisation. As my colleague Vilnis Vējš commented in his review of of the Vilnius chapter of BT13, the meaning of the expression arises from the particular combination of words [instead of from each individual word’s meaning], and is linked to ‘the linguistic environment from which the expression originates’. If one transfers this idea to the visual arts, then it could be said that the four different languages in which the title of the Triennial is expressed do an impressive job of reflecting the peculiarities, values and so on of not only the whole region, but of each individual nation as well. However one may translate the title of the Triennial, it is safe to say that it was not decided upon single-handedly by its artistic director Honoré, but that it is rather the whole Triennial team’s conception of current world events.

Nina Beier. Automobile, 2017

Unlike its predecessors, the execution of this year’s BT was delegated to a broad and diverse group of participants: the artistic director enlisted for each of the chapters a ‘sub-curator’ that he believed was suitable for the job, as well as a team of professionals working at the relevant institution. Except for those responsible for the visual concept of BT, including exhibition architect Diogo Passarinho and graphic designer Tadas Karpavičius, each chapter was realised by a different working group, which makes for yet another aspect from which the Triennial can be viewed. Namely, can the project be observed and (just like the words in its title) be perceived as a whole? Or is it a realisation of three independent, consecutive exhibitions? This is indeed the same aspect that Vējš underscores in his review, titled What is left over, on the Tallinn chapter of the Triennial, in which he points out the elementary fact that most of the people who will see the Triennial will have seen only one of its chapters. In addition, in another one of his Triennial reviews he punctuates that one’s core identity is made up of the person him- or herself, or an object that belongs to him or her (and equally in regards to any which level of ‘belonging’). Subsequently, only those who have been given permission can [morally] become a participant in the creating of an identity. Here we can draw parallels with the Baltics’ political history, according to which it is possible to identify both shared and regionally characteristic traits in art, as well as the relationship to the world as experienced by each individual who has grown up here.

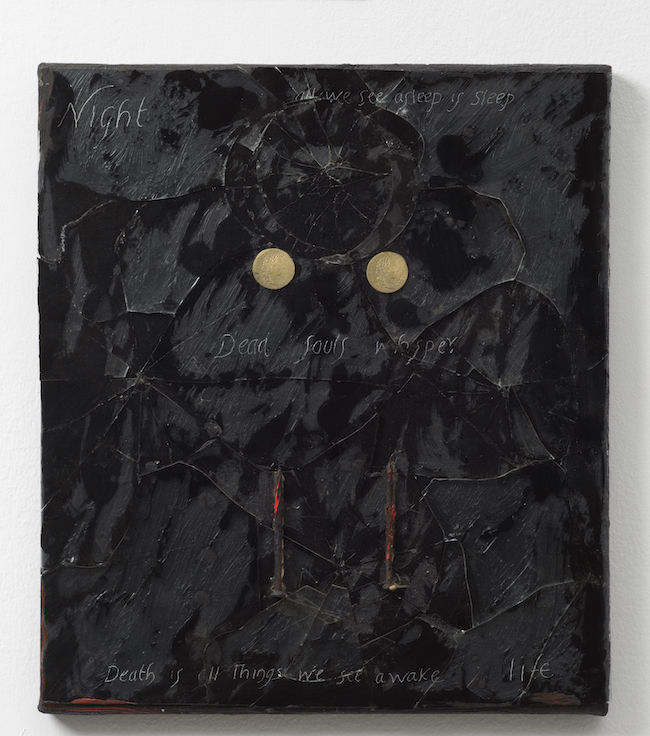

Derek Jarman. Dead Man's Eyes, 1987

In his official statement on BT13, Vincent Honoré emphasises that the essential question (‘what does belonging mean in this time of fractured identity?) has been left partly unanswered; in its place, viewers are offered ‘a collective vision of what is at stake: independence and dependency – and everything that lies in between – territories, cultures, social classes, histories, bodies, and forms’. Although these concepts can be generalised to a high degree, in the centenary context [ergo, absolutely in a political context as well] they associate with experiencing the past of the Baltics and the ghosts that still remind us of this past. This is also substantiated by the concept of belonging that is so essential to the exhibition – being a representative of some group (regardless of kind, be it ethnic, religious, professional or leisurely pursuit) is a kind of security guarantee; it is no secret that in the 21st century, when more than half of the world’s population suffers from ‘vegetative dystonia’, one of the underlying causes is precisely a lack of security (i.e. belonging). Perhaps that is why the BT team actively gravitated towards involving artists of international caliber. Zane Onckule reveals that making up the list of participants for all of the exhibitions became a part of the Triennial’s central concept, and that emphasis was not placed on works of artists from the Baltic region but rather on creating a representation of international contemporary art: ‘For each of the participating countries, BT13 has been an educational and informative process on the current workings of the art world. Beginning with the artistic director and his team of curators, and ending with the organisers, the Triennial has been an exciting process in which to discover what is going on beyond that which is already known and familiar.’

Ben Burgis un Ksenia Pedan. Celf Haul, 2017

1Source for this and other quotes: 2The Baltic Triennial of Young Contemporary Art in Lithuania