A glimpse at the current discussion on biennialism.

On the occasion of the 13th Baltic Triennial

Indrek Grigor

08/11/2018

The past summer in art criticism was filled with discussions concerning biennalization, i.e. the constant birth of new biennials and the continued growth of those already established. It makes sense to take a glimpse at the discussion not only because the first installment of RIBOCA (Riga International Contemporary Art Biennial) just wrapped up, but also due to the currently ongoing Baltic Triennial exposition Give Up The Ghost at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. And perhaps somebody still remembers Riga Photo Month and the Riga Photography Biennial, both of which took place this last spring? As for the international media, the discussion (in central Europe) was, first of all, focused on Manifesta and the Berlin Biennale, but also worth mentioning are the 33rd São Paulo Biennial, the 10th anniversary of the Liverpool Biennial, and Art Basel, the latter of which even hosted a discussion titled Public/Private | What Can a Biennial Do?

Rayyane Tabet. Steel Rings. Palazzo Ajutamicristo

According to the Frieze September issue, there are around 200 biennials worldwide. Unfortunately, Frieze does not list the source for this claim. A much more reliable assertion appears to be a Swiss survey published in a special June issue of the online magazine On Curating, which claims that there are 316 biennials. Equipped with nice looking graphics, the survey gives an exhaustive overview of the chronology and geography of biennalization but, unfortunately, the data lacks further elaboration.

Yet even the scientists in Zürich are rather imprecise about their sources. After mentioning two larger online sites that have compiled a list of biennials, they refer to all other sources as the results of online searches. Based on my own purely empirical observations, 316 is, by far, not a full count of all the biennials being held in the world. Part of the confusion seems to arise from there not being any fixed parameters by which to judge whether a biennial is a biennial. When Jane Morris raised the question in her article Is the Biennial Model Busted? as published in The Art Newspaper, she wrote not only about exhibitions that take place biennially, but also about triennials and, of course, Documenta, which follows a five year cycle. So, ultimately, there is no reason to believe that even annual festivals could not be described as being biennials when talking about the phenomena of a major international contemporary art event. Therefore, the remaining questions, I would argue, concern the definitions of ‘major’ and ‘international’.

One of the biennial problems mentioned by Jane Morris is the human factor. Do we have a sufficient amount of curators and artists who can annually produce the required amount of significant works to fill the demand? When confronted with this concern in a discussion round, Kirill Kobrin, a Russian-born cultural historian living in Riga, answered with a rhetorical question. ‘How many rock festivals are there every year? And how many bands actually produce a good album?’ What his comment reveals is the fact that biennalization – in the sense of a marked increase in growth of grand cultural events, both in number and size – is nothing particular for the art field. It’s quite the opposite, actually, in that it’s a much broader phenomena that can be seen to be taking place in the cultural industry as a whole.

Nikos Navridis, All of old. Nothing else ever... 2018

The answer to what the word ‘international’ means in a description of a biennial has been nicely summarised by Orit Gat’s review of the 13th Baltic Triennial published in the September issue of Frieze. Gat ends her review with: ‘Maybe we have reached a point at which international biennials can't tell us much about the locations that we inhabit, make work in, and discuss; maybe the ghost we need to give up is the expectation that art and exhibitions reflect on the world we live in and, instead, settle for the sheen of the global.’

It would be wrong to claim that the biennials themselves are not aware of the situation. It seems to me that the current discussion was triggered by Documenta 14. Traditionally taking place every fifth year in Kassel, Germany, this time Documenta decided to make a satellite event in Athens, Greece – the currently financially challenged and migrant-crisis-torn cradle of European culture. Documenta's colonial ambition – a display that had grown so big it was unmanageable even for the most dedicated visitors – and the financial scandal that erupted while the event was being held, has been harshly criticised in almost every article on the topic of biennialism. Obviously, it was impossible for the institution of the biennial to not react to the situation. Suzanne Falkenhausen, who in the aforementioned Frieze special issue on biennials analysed Manifesta and the Berlin Biennale – two events that have had some success in the fight against the machine – now sees the ghost in a totally different place. Falkenhausen concluded that self-critical curatorial practices that try to avoid the colonial gaze of an international biennial could ‘lead to the end of the biennial as a platform for political articulation and aesthetic engagement.’

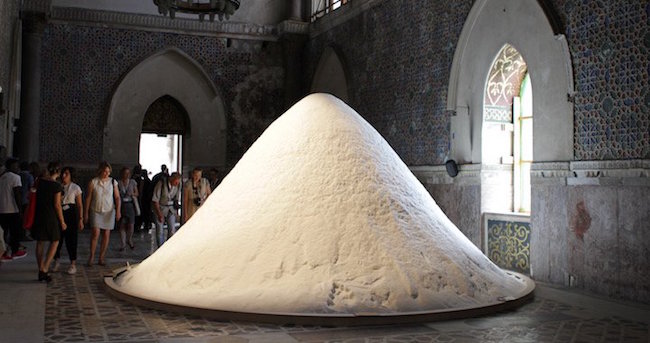

Patricia Kaersenhout. Soul of Salt. Palazzo Forcella de Seta. Photo: Ģirts Muižnieks

Manifesta, which took place in Palermo this year, did not hide its role as a promotional event for the city. Art was turned into a tool to serve the public. And the conservative display of the 2018 Berlin Biennial wore the face of African, Asian and Latin-American female artists whose interests were set into the middle point of the curatorial choices in order to avoid an influx of Western identity/political cliches. Falkenhausen refers to a parallel situation that took place in Germany in 1989, when Western female art historians turned to their Eastern colleagues to join forces in writing a feminist art history, but were turned down as the Eastern historians were much more interested in broadening their disciplinary skills and reading up on research that had been off limits until now – ‘That was the freedom they desired most.’ Following a similar model, the 2018 Berlin Biennial focused on traditional artistic skills, which seems a rather outdated take on art in the European context. Falkenhausen summarises her experience of Manifesta and the Berlin Biennial exhibitions as follows: ‘With both biennials, I have the strong feeling that the exhibition is not their most important element. As a spectator, I felt like a visitor in a community of artists, curators, collaborators, activists, cultural operators and city administrators that establishes itself temporarily during the long process of putting the biennial together.’ I couldn't agree more.

Michael Landy, Open for Business. 2018

But nothing like this could be said about RIBOCA, which was, for the Baltic region, the most important biennial this year. RIBOCA’s exhibition was a classical display of contemporary art. I felt like I was in a big contemporary art museum, where everything is beautiful and safe. But whereas RIBOCA’s curator, Katerina Gregos, was at least expressing awareness of the problem of biennialisation, the other European biennials didn’t really care about reflecting critically on their status. Quite the opposite, actually – the Baltic Triennial, in effect, bragged about how well it has integrated into the European circuit of biennials as the strongest showcase of Baltic art. And even though the annual Survival Kit cannot use the magic buzz connected with the status of a biennial, it can, nevertheless, claim to be ‘the largest annual event in the Baltics’, taking into account that size and growth are the most talked about features of a biennial.

The previous Baltic Triennials, starting from 1979, have all taken place in Vilnius. But since all three Baltic states are celebrating their centennials this year, there was an inter-Baltic commission for events to celebrate the occasion. The Baltic Biennial found itself employed into this role which is why, for this iteration, it travelled from Vilnius to Tallinn, and is now finishing up in Riga. I had initially planned to visit all three venues in order to adequately critique the whole event, but unfortunately I could only manage to get to Riga.

Baltic Triennial exposition Give Up The Ghost at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre. Photo: Andrejs Strokins

Kim?, which houses the Riga installment of the triennial, is a much smaller space than both the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius and Tallinn Art Hall, which is why the question of how the triennial would be exhibited in Riga intrigued me from the start. The end result was excellent and a total disaster, both at the same time. I did not make it to the opening event, but when, the day after, I met a colleague on my way to the performance event at Kim?, he managed to totally confuse me with the claim that there had been an opening of two exhibitions. The dual show, he said, was apparently pretty good, but the triennial itself is a disgrace. When I eventually spoke to other people about the show at Kim?, they also expressed their opinion of the first room being pointless, but that they really liked the other exhibition. The thing is, from all of the artists participating in the biennial, only the artistic partnership of Ben Burgis and Ksenia Pedan has been properly displayed; the rest of the triennial is represented only by a selection of objects and videos. Moreover, it's not quite clear whether these are whole works or just fragments. Kārlis Vērpe, whose review on the Baltic Triennial will be published in Echo Gone Wrong, asked me: ‘What makes a biennial?’ I answered: ‘This room.’ A biennial cannot, by definition, be a one-man show. Taking that into account, I am rather happy that the curator did not try to dissolve a larger number of works into Kim?, but allowed for Ben Burgis and Ksenia Pedan to shine. Sacrificing one room in order to prove that it is, after all, a ‘biennial’, is a curatorial compromise that I personally don’t approve of, but I guess that in this case, it was necessary.