Tate honours Dóra Maurer, a legend of Hungarian conceptualism

08/08/2019

The retrospective of eighty-two-year-old Hungarian artist Dóra Maurer (1937), on show at Tate Modern in London from August 5 of this year until July 5, 2020, is significant for at least two reasons. First of all, it’s an undeniably outstanding celebration of the half-century-long career of a legend of Hungarian conceptual and experimental art. This is underscored by the fact that the exhibition, which is open to the public free of charge, stands alongside a number of other new, free displays at Tate Modern, including a series of graphic woodcut prints by Sol LeWitt (1928–2007), David Goldblatt’s (1930–2018) powerful images of apartheid South Africa, and a room full of recently acquired photograms, films, paintings and drawings by Polish émigré artists Franciszka Themerson (1907–1988) and Stefan Themerson (1910–1988).

%20Tate%20(Matt%20Greenwood)_4.jpg)

Installation view of Dóra Maurer at Tate Modern, 2019. Photo Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood)

But the Maurer retrospective also indirectly confirms the gradually increasing interest of prestigious art institutions (MoMA, the Centre Pompidou, etc.) in 1960s and 70s art from Central and Eastern Europe. “International institutions started to research this period, and they found important links between the avantgarde and neo-avantgarde generations. Parallel to this, a group of collectors from the region were invited to the acquisition committees of major museums. Their knowledge and support also help this process,” says Attila Pőcze, the owner of Vintage Gallery in Budapest, which represents Maurer.

Trained as a graphic artist and printmaker in the 1950s, Maurer appeared on the art scene in the 1960s as a member of Hungary’s avantgarde generation. She worked in a particularly experimental niche that ran parallel to the “official” art system dominating in Hungary at that time. This generation of artists organised exhibitions in private apartments and published underground journals. As an artist, Maurer was most prolific and innovative in the 1970s, when, following her experiments in printmaking and stretching the borders of that genre, she turned to conceptual photography, structural film and process-based drawing.

Maurer’s work took processes that often included seemingly simple, everyday actions and made them much more visible, in a way also visualising the energy invested in the processes. In 1971 she created a series of black-and-white photographs (the documentation of a performance that had taken place that same year) embodying an apparently straightforward question and simultaneously also its answer: What Can One Do with a Cobblestone? Organised in a grid of fifteen photographic prints, the photographs illustrate the spectrum of all one can do with a simple cobblestone. In one of the images, for example, Maurer wraps the stone in paper and then sets it on fire. Needless to say, the stone “survives”. In another image, she washes the stone and caresses it with a loving, motherly touch. These seemingly carefree experiments are given an associative tension and a relevant political context by the fact that cobblestones are often one of the spontaneous weapons used during street protests.

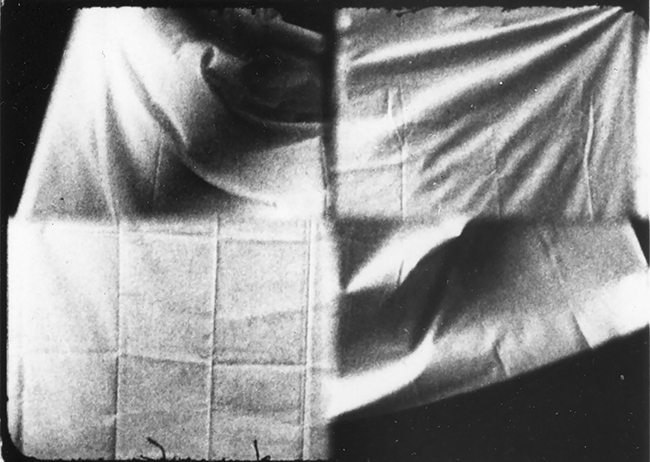

Timing, film still 1973/1980. Film, 16mm shown as video, projection, black and white. Tate, © Dóra Maurer

Much of Maurer’s work centres on movement and shifting, and it is inspired by the relationship between mathematical methodology, possibility, chance and freedom. Between perception, assumptions and transformation. Her work is about the world of limitless possibilities and interpretations, and she often calls her pieces a “novel in pictures”. They analyse and call attention to common, everyday gestures by, for example, not only illustrating an action but also inviting one to feel it. Therefore, in addition to the distinctly conceptual character of her work, critics always also emphasise its subtle humanity. Her works of art are emotional experiences that seem easy to interpret because they centre around supposedly self-evident, repeatedly tested actions that each and every one of us can relate to both on the physical and visual level. Her works are like easily perceived signs whose (often laconically minimalist) imprints form a contemplative narrative.

The exhibition at Tate Modern contains a total of thirty-five works by Maurer ranging from her series of conceptual photographs and experimental films to her graphic works and striking geometric paintings, in which she studies geometric forms and the way in which they are influenced by colour and our perception of colour. Among these are Seven Foldings (1975) as well as five films Maurer made in the 1970s and 80s, including Triolets (1981) and Timing (1973/1980), which feature the repetition of activities, movements and rotations that have become characteristic of Maurer’s practice.

Seven Twists V 1979, printed 2011. Gelatin silver print on paper, 20.5 × 20.5 cm. Tate, © Dóra Maurer

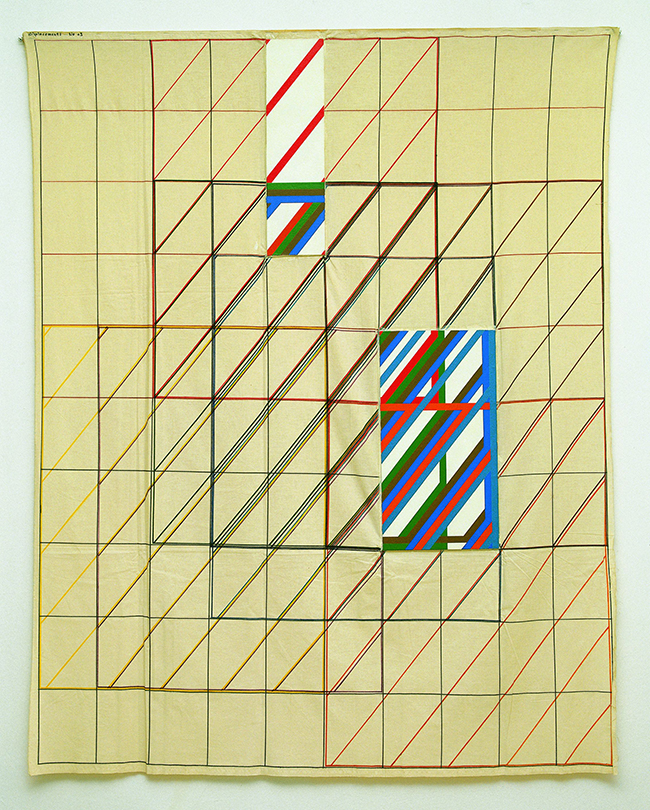

Displacements, Step 18 with Two Random-Quasi-Images 1976. Acrylic, canvas, wood, 200 × 160 cm. Promised gift to Tate by anonymous donors, 2019. © Dóra Maurer

A separate area in the exhibition space is dedicated to such significant project in Maurer’s career as her 1983 work for Kunstraum Buchberg, one of the most unique private art spaces in Austria. The medieval castle on the outskirts of Vienna houses the one-of-a-kind art collection of Gertraud and Dieter Bogner, which consists of more than thirty site-specific installations of conceptual art. Maurer’s geometric colour installation in one of the castle’s rooms was the first site-specific work of art to be displayed at Buchberg and became the foundation of the Bogner collection. For her own career, it was an opportunity to expand her painting into a three-dimensional space. In an interview with Arterritory.com, Dieter Bogner remembered curating an exhibition at the Modern Art Gallery in Vienna that also included work by Maurer, and she expressed interest in painting one of the rooms in the castle. “She was so happy, and so were we. Later on, she developed an actual series of work out of these elements,” says Bogner.

“It’s really a coronation for Dóra Maurer – for being such a fantastic artist and being brave enough to experiment all the time,” says Hungarian businessman and philanthropist Péter Küllői about the exhibition at Tate Modern, adding that, despite her age, Maurer is still active as an artist. “It’s very often the case that when artists become successful, they forget the bravery and begin repeating themselves. This is not Dora’s case.”

Maurer has also long worked as a curator and a professor at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Budapest. “She had a very special role in distributing Hungarian art internationally,” says Pőcze of Budapest’s Vintage Gallery. “Since 1968, she has lived in both Vienna and Budapest with her husband, Tibor Gáyor. They were able to travel between the two countries and thus distributed work by their artist friends internationally. Dóra organised exhibitions and workshops from the early 70s onward and was a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, supporting a younger generation of artists.”

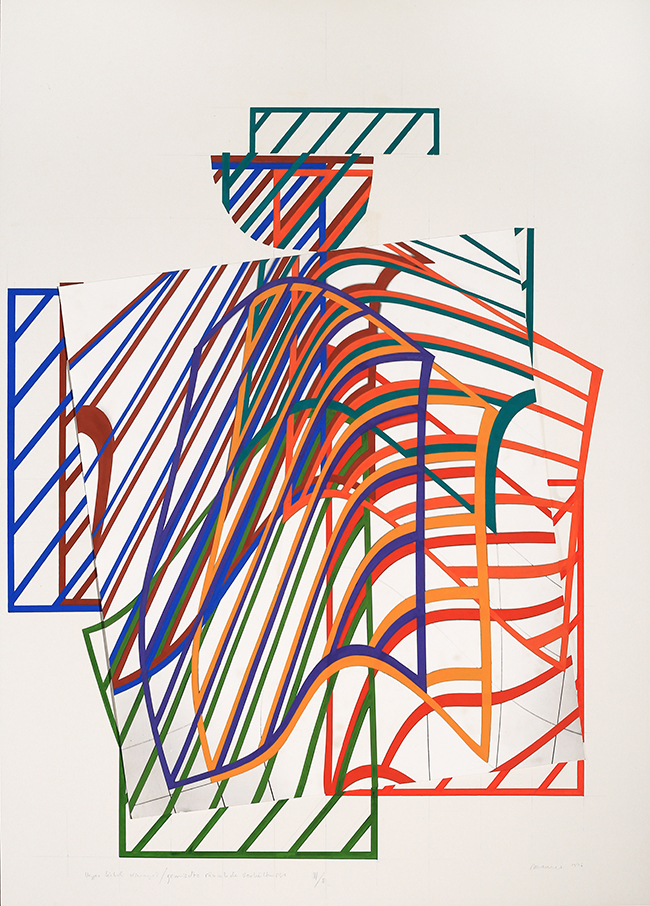

Space Painting 1984–96. Silver print, gouache, 100 × 70 cm. Private collection. © Dóra Maurer Photo: Vintage Galéria / András Bozsó

Maurer, for her part, has always resisted this “Hungarian artist” description. In a 2012 interview with ArtReview, she insisted that “there is no necessity to characterise artworks by their nationality. As far as I know, Hungarian fine art has no special character; it was and is European. A Czech art historian said she saw my Space Painting made in Austria and that it is a typical Hungarian work. Since then, I have seen similar colourful installations made by a Czech artist. That I am a Hungarian painter or artist, no. However, I am not an Austrian, not a Norwegian, not an American. I am a human being.”

“Maurer’s pioneering work is characterised by both rigorous self-discipline and playful experimentation. Movement, displacement, perception and transformation have remained consistent threads in her work. Maurer remains a unique voice, constantly in motion – never tied down to one medium and constantly pushing her playful conceptual practice,” says Juliet Bingham, Curator International Art at Tate and the curator of the Maurer retrospective, when asked what makes Maurer’s work so important in the context of art today as well as in the context of international audiences (considering that the retrospective will be on show for almost a whole year). “Maurer’s conceptual ‘action-graphics’ from the 1970s onwards – for example Metal Plate Dropped from a Great Height (1970) – set the picture plan in motion. Her guiding concepts – across all media – were movement, displacement and the constantly shifting and changing concepts of the picture and of art.”

Bingham continues: “Maurer’s inventive approach to image-making in her moving image works includes multi-perspective shooting (Relative Swingings), use of temporal, optical and sonic registers (Triolets), and her exploration of the apparatus of film itself (Timing), alongside other phenomena, such as combining formal experimentation with a psychological study (Seven Trials 1981–2). Her collaborations with musicians, for example, creating colour-sound environments (Kalah, 1980), are remarkable as are her proposals for unrealised ‘expanded’ film and projection-performance. Maurer’s expanded painting practice is notable, particularly in relation to her Space Painting, Buchberg Project (1982–3), which embraced formal experiments in time, geometry and colour. In addition, her wide-ranging activities – as an artist, teacher, networker and curator – have been influential not only for those ‘unofficial’ artists associated with Hungarian neo-conceptualism during the socialist period but also for younger generations of artists today.”

%20Tate%20(Matt%20Greenwood).jpg)

Installation view of Dóra Maurer at Tate Modern, 2019. Photo Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood)

%20Tate%20(Matt%20Greenwood)_2.jpg)

Installation view of Dóra Maurer at Tate Modern, 2019. Photo Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood)

Spread over five rooms at Tate Modern, the exhibition shows Maurer’s oeuvre chronologically, indicating the strong connections between different periods and mediums, and focuses on the themes of movement, displacement, perception and transformation that Maurer continues to explore in her work today. Asked to highlight a few works that she believes form the core essence of the exhibition, Bingham mentions three conceptual cornerstones of the show:

1) “Maurer’s moving image works from the 1970s onwards reveal her interest in the structure and mechanisms of the medium as well as the use of conceptual language focused on the process of art making. Repetition of activities, be it folding, overlapping, distortion or rotation, are a characteristic feature of Maurer’s practice, spanning all the media she uses. Her approach is underpinned by a systematic principle of tracing subtle differences and achieving complex results with basic means. Her film Triolets (1981) unfolds as a puzzle, with three perspectives moving in opposite directions. Using three camera lenses, the film is made of one-second camera pans shot inside her studio, collaged to form three different views and accompanied by a soundtrack of layered vocal glissandi.”

2) “In 1983, a commission to make a site-specific project at Schloss Buchberg (Buchberg Castle) near Vienna gave Maurer the opportunity to realise her ambition of expanding her painting practice into three-dimensional space. Visitors entering the room would find themselves physically embraced by the pulsating interplay of painted lines. The film Space Painting, Buchberg (1983) is both a documentation of the environmental painting that she created for the castle and the expression of a subjective experience and the action of painting. The Buchberg Castle project was an important moment in the development of Maurer’s practice as it highlighted to her that colour sensitivity is time-based, that colours ‘shift’ with changes in the light. While trying to film the various phases of the work using a small Super 8 camera, she found that she repeatedly had to switch colour filters as the day progressed and the light conditions changed. The work opened up new possibilities to move away from her use of standard colours without completely abandoning her system.”

3) “The exhibition culminates in a room of Maurer’s recent paintings, including the breathtaking painting/installation Stage II (2016). Here, colour is used on the flat surfaces to produce the illusion of a three-dimensional object and a feeling of movement through the use of overlapping colours and planes that float and have a sense of transparency. The artist herself refers to these experiments as ‘form gymnastics’. The apparently moving and floating shapes underline once more that, in Maurer’s universe, everything is in motion and everything is relative.”

%20Tate%20(Matt%20Greenwood)_3.jpg)

Installation view of Dóra Maurer at Tate Modern, 2019. Photo Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood)