The Modigliani wish list

Interview with Nancy Ireson, curator of the Modigliani show at Tate Modern

18/01/2018

It’s been some time now since the long-awaited Modigliani show opened at Tate Modern. The first reviews have been published, calling the exhibition mesmerising and generously giving it five stars. Somewhere along the line it was also described as “a gorgeous show about a slightly silly artist.”

Well, Amedeo Modigliani was everything but not silly. His name, his tragic story, the controversy around the Modigliani fakes, the drama about the money art collectors are ready to pay (whatever it takes!) to acquire his extraordinary, distinctive paintings, as if owning his work were like possessing something divine. It’s all just a few steps from where I wait to meet Nancy Ireson, co-curator of the Modigliani show. I want to ask her about what it takes, under such circumstances, to put together a show like this.

Ireson was appointed a curator of international art at Tate Modern in 2015 after previously working at the Art Institute of Chicago since 2013, where her work included the Temptation! The Demons of James Ensor exhibition. In 2011 she curated Toulouse-Lautrec and Jane Avril: Beyond the Moulin Rouge at The Courtauld Gallery as well as Cézanne’s Card Players (together with Barnaby Wright) in 2010. Now Ireson is working on the exhibition Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy, which will open in March at Tate Modern.

But back to the organisation of the Modigliani show. As it turns out, the first thing it takes is to put together a wish list.

Self-Portrait as Pierrot. 1915. Oil paint on cardboard, 430 x 270 mm. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

How did you feel before the show? Were you sure it would be a success? Considering that Modigliani’s name needs no further explanation in the art world.

It’s always difficult to know with an exhibition, especially because Modigliani is outside the traditional art history canon. I think it’s interesting that so many accounts of early-20th-century art have sidelined Modigliani. It was exciting to explore him as a serious artist and present a wide range of his work. And now to have such great reviews and reactions from all different quarters – from our general audience to specialists – it’s been very encouraging.

I remember at the press preview, Frances Morris, the director of Tate Modern, admitted that, even reading art history at Cambridge, he was never a subject of study. In a way, he had been lost in the history, forgotten. Why do you think that happened?

There are a couple of reasons. One of them, I think, is because ideas of what was progressive in the early 20th century tended to revolve around abstraction, and Modigliani did not work in an abstract style. If you’re telling a story about Cubism, or Futurism, or Purism, Modigliani doesn’t belong to the narrative.

The other thing is his lifestyle. For a long time, the shock of the way he lived made it harder to take him seriously. Nowadays we have less trouble admitting, for instance, that – despite the drugs and wild parties – the Rolling Stones changed popular music. In a sense, it’s the same thing with Modigliani. Yes, he was an alcoholic; yes, he took various substances; yes, he had numerous relationships; but at the same time, he created extraordinary art that has made a massive impact. Now, with historical distance, it’s easier to see that difference, rather than get wrapped up in the sensationalism of the story, which is what happened with a lot of earlier accounts of Modigliani.

Portrait of a Young Woman. 1918, oil paint on canvas, 457 x 280 mm. Yale University Art Gallery

Have there been serious recent exhibitions of Modigliani’s work?

There have been strong exhibitions periodically. In London, at the Royal Academy of Arts, there was a very good show in 2006, which was created by my colleague Simonetta Fraquelli, who is co-curator of this exhibition. It was a small show and had a more limited scope.

There have always been serious individuals interested in Modigliani. Hugh Blaker, curator of The Holburne Museum in Bath, bought one of the paintings that’s now in Tate’s collection (The Little Peasant, c. 1918 – Ed.) as early as 1919. Picasso thought Modigliani was an exceptional artist and bought one of his paintings in the 1930s. There have been moments of serious recognition. But more generally, if you compare it to the number of exhibitions that have focused on Matisse or Picasso, they are relatively rare.

How did the idea come about to create this show at Tate Modern?

We’ve been working on this show for about two years, and it’s been something our visitors had been asking for for a long time; Modiglianis in the Tate collection have always been well loved. I joined Tate at the end of 2015, and the timing seemed to work very well.

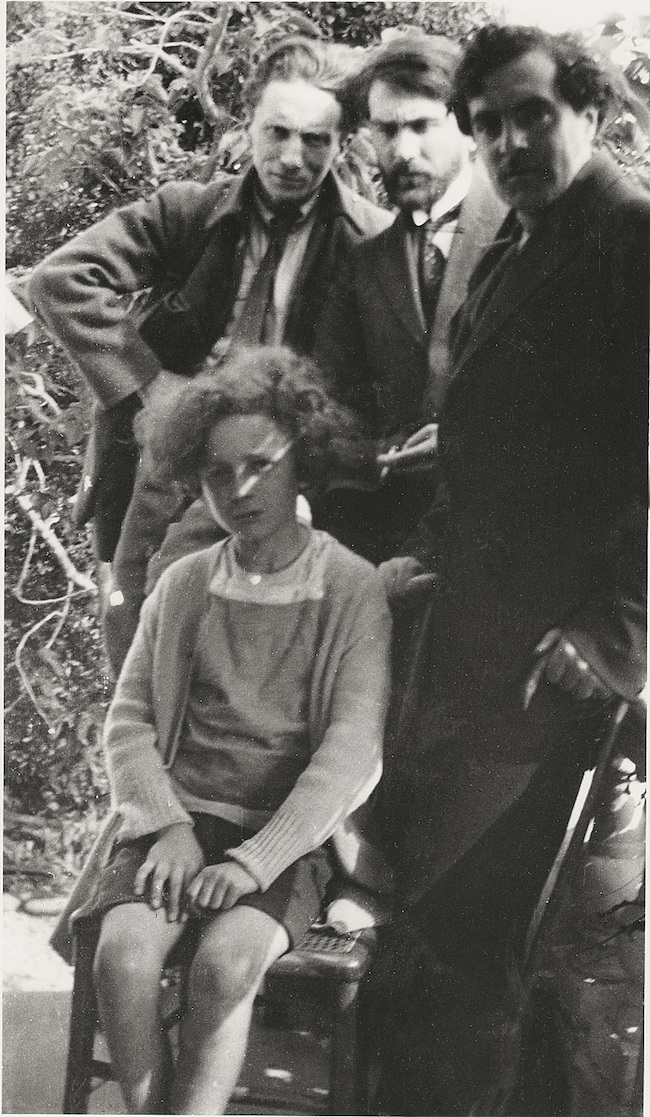

Amedeo Modigliani, Léopold Zborowski, Anders Osterlind and Nanic Osterlind, Haut-de-Cagnes 1919. Association Anders Osterlind

Do you remember what was the first thing you did when you started this project?

We decided very quickly on approaching it from the angle of Modigliani’s arrival in Paris: a sense of developing his style and personality through that experience. And then we did what you would do when planning any show – you start to build a ‘wish list’.

Modigliani produced far more work than we could show in one exhibition, so we started with a selection of pieces that we felt were the strongest, pieces we felt would bring out his story in a meaningful way.

Some of the most complex things to achieve were bringing together representations of the same women dressed and undressed. For example, we’re delighted that we have two paintings of Elvira. Standing Blonde Nude (Elvira), painted in 1918, is borrowed from the Kunstmuseum Bern (Switzerland), while Elvira Resting at a Table (1919) is from the Saint Louis Art Museum (USA). To see the two of those together is amazing, bearing in mind that both of the pictures have very rarely travelled, and to have them both together here in one place is very special.

Another achievement that we never dreamed would be possible is to have nine of Modigliani’s sculptures together. That’s about a third of his known sculptures. To be able to assemble that group is incredible.

Was it challenging?

To put on an exhibition like this is very difficult, because these paintings are so well known and you ask a great deal of an organisation in asking for a loan. They are often the highlights of a museum’s collection, and it’s very difficult for institutions to be without those pictures for five months. We have 100 works here from 72 different lenders. Because again, the nature of collecting Modigliani means that often people have only one piece or maybe two pieces. It’s not like borrowing paintings from an artist’s foundation.

Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz. 1916, oil on canvas, 813 x 543 mm. The Art Institute of Chicago

Head, c.1911. Medium Stone, 394 x 311 x 187 mm. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Lois Orswell © President and Fellows of Harvard College

There are paintings in this show that have not been exhibited for a very long time.

Certainly, there are paintings here that have not been shown in the UK at all, which is very exciting. And there are a lot of works that have not been seen in public for a very long time. Something like the double portrait from the Art Institute of Chicago, which hasn’t been here since the 1950s (Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, 1916 – Ed.), is exceptional! Also, for example, the Head that comes from the Merzbacher Collection, which we only knew from a black-and-white photograph at the beginning.

Were there long hours and a lot of stress?

Absolutely! I think I can speak for my co-curator Simonetta as well, to say that to curate an exhibition is a labour of love. It has to be. In order to create something exceptional it takes an exceptional effort. But there’s a lot of enjoyment, too, which goes with the long hours.

What do you personally find fascinating about Modigliani’s artwork?

I love the expression of character, the constant engagement with the figure and with individual personalities. That, I think, is evident from these early experimental works onwards. Whilst he tried a lot of different things formally in terms of the treatment of the face, and even when things are stylised to the extreme, you still have a sense of a person. And walking through the rooms of the exhibition you really do have this feeling of those characters. I think that sense of connection is very strong.

It’s a great privilege to work with some of the best art of the 20th century. I mean, it’s one of the wonders of working in a museum, that you are able to reunite pieces and to tell a new story. And with this particular exhibition you also get to introduce a new generation to an artist. Tate Modern is known as a museum for modern and contemporary art, and Modigliani is an artist who does bring generations together. It’s very heart-warming to see people coming out from the exhibition having shared that experience.

But you’re dealing with works of art that cost millions. Tens of millions.

One of the joys of working for a public museum is that our view of works is not about the price tag but about the art’s value historically, its value socially and its value visually. We have a chance to celebrate that. Every work in our collection is cared for. We have an amazing conservation team, we monitor our climates very carefully, and everything is done to protect the works that we show. It’s true that market values of Modigliani are incredible, and we wouldn’t be able to do these kinds of projects without the Government Indemnity Scheme,* which provides the incredible level of insurance required. But for us, the real value of these works is not monetary.

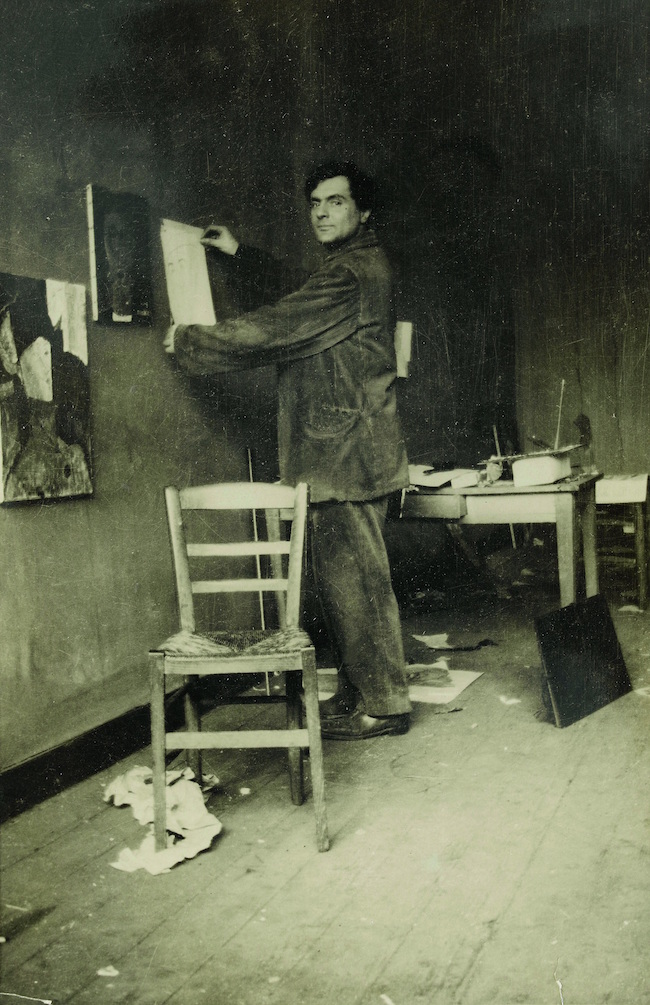

Modigliani in his studio, photograph by Paul Guillaume, c.1915. © RMN-Grand Palais (musée de l’Orangerie) I Archives Alain Bouret, image Dominique Couto

One of the things that make this exhibition so very special is the virtual reality experience. “The Ochre Atelier” is a chance to visit Modigliani’s last studio in Montparnasse and see it as if the artist himself had just left the room. In a way, the whole exhibition suddenly made more sense. The VR experience gave it greater depth and left an indelible impression.

I’m really glad you had a positive experience with it, because we didn’t start out by saying we want to create a special VR project. We very much started with the idea of an exhibition, but we were also interested in how we could use technology to help visitors to connect more immediately with what they were seeing. Through talking with our digital team here at Tate, the idea came about very organically. As curators we were not familiar with virtual reality, but we started to talk about what we wanted to create, the stories we wanted to tell, and our digital team told us about the methods available. We developed a partnership with HTC that made the whole thing possible.

Every stage of the process has been collaborative – it had to be – because, in a way, we needed to challenge each other. We would research information that we would then pass on to our digital team to figure out how we could actually include it in the VR experience. But then the developers, a company called Preloaded, would ask us, for example, what would the back of this thing look like? It was a very interesting process and certainly something that we feel has been very valuable.

Tate has got a reputation for pushing boundaries in terms of how we engage with art, and this felt like a really exciting new way of exploring what was possible.

At some point it felt almost like a sci-fi experience, when you could press a button just by looking at it and then hear the story. There I felt the real value of technology.

Yes, it’s very much technology in the service of connecting with art. It’s about having an experience that helps you engage more fully with the canvas in front of you. We went through various rounds of testing as we developed our VR experience, and we very much liked that feeling of discovering something by yourself. You choose what to look at, and then it plays out in front of you, and again it helps us feel so immediately connected.

The window was open and it was raining outside, and a candle was lit and a cigarette was burning in the ashtray...

In terms of content resources, we worked with a colleague based in Paris, Vincent Gille. He helped us to add depth to the environment. We had the contemporary accounts, and we made sure we had accurate translations of those, so what you hear in the VR tour is the exact words of people who knew Modigliani and knew his apartment. Vincent was able to help us with historical details, because we don’t have photographs of the studio from 1919. We could say to him that, for example, we have a description of tins of sardines or we have a description of a stove, and he would then look for what was accurate for that moment in time and send us various images, which the artists in our digital team could then work with and model those things in the virtual world. There are a lot of historical details in the experience.

Nude, 1917. Oil paint on canvas, 890 x 1460 mm. Private Collection

Does the actual physical space of Modigliani’s studio still exist?

Yes, it’s still there in Montparnasse. The developers went into the studio and they measured everything – the size of the walls, the size of the windows, the height of the ceiling, all come precisely from the actual space. It’s a modern apartment now. It doesn’t look like it does in our VR tour, of course, but it’s still there. And the view out of the window is pretty much the same, because it’s a 19th-century apartment from which you can see the rooftops of Paris, which are all still the same 19th-century rooftops.

What were your own impressions of the VR experience?

I saw it at various stages during the process, and it was very exciting each time to see new layers of depth, new details appearing, and to provide feedback if something didn’t feel right or if the colours seemed to not be accurate. I’m very happy with the result. In a way, there’s something quite magical about what it creates. It’s very special.

This is the first time a show has used VR as an integral part of a historical narrative. It isn’t that you have an exhibition and then you have a digital experience; it’s actually as much a part of the exhibition as are the wall texts. It’s something that has a seamless connection with the rest of what we present.

After the VR tour, the next room of the exhibition is the last one. It’s called “An Intimate Circle”, and it’s where mostly portraits of Modigliani’s partner, Jeanne Hébuterne, are exhibited. And for five seconds I was there all by myself, enveloped by her watchful gaze.

Yes, that room is very intense.

Especially after the VR experience.

I’m so pleased that you say that. Because as curators we felt that it’s a lovely way of having a very strong connection at the end of the show. Because sometimes, after an hour looking around an exhibition, you’re just thinking about where you’re going to go next, what you’re going to do next! That’s why there’s something amazing about leaving having felt a new level of connection with the work. I think it also helps to consolidate everything you’ve seen up until that point.

Do you have an answer to who Modigliani actually was? There are so many books written about him, even movies made.

The thing we wanted to show in this exhibition is that he was an artist who really had an understanding of how to use materials and how to create very distinctive images that were entirely his own. That’s why I sometimes think of him in terms of these analogies with musicians – people like Amy Winehouse – because it’s about the art rather than the lifestyle or the romance. There are lots of people who have wild lifestyles or who struggle with addiction, but we don’t always recognise them or remember them. It’s the work that counts. And that, for me, is what you sense when you see this show – the power of what he achieved.

What do you think what was his biggest strength as a person?

He was very dedicated to following his own path. It must have been incredibly difficult to be an artist in Paris in the early 20th century. There was so much going on! So many styles and movements you could associate with. In a sense, they became quite orthodox – the futurists were quite frustrated that Modigliani didn’t want to become a futurist; the cubists found that it was awkward that he didn’t adopt cubism. To be so sure of what you want as an artist, I think, is a real achievement.

In a way, he was ahead of his time, because in the 1920s, after the First World War, a lot of artists moved back to figuration. It’s almost like because of that experience of a conflict, people needed to reconnect with something complete and something very human. But Modigliani never needs that, because he already does that. It’s almost as if he takes that tradition he grew up with – those Italian roots, the history of art more generally – and brings it into the 20th century. There’s never rapture. It’s that sense of guiding it through rather than starting again.

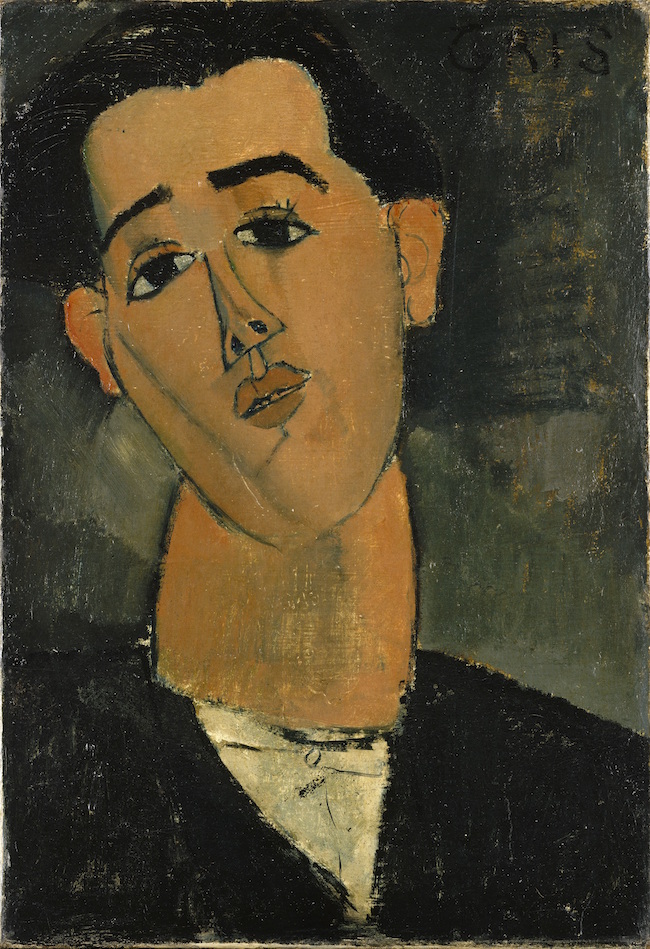

Juan Gris, 1915. Oil paint on canvas, 549 x 381 mm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

And his biggest weakness?

Through no failing of his own, I think his biggest weakness was the literal weakness of his health. It would have affected the way he worked. It probably contributed to his lifestyle choices. If you’re constantly dealing with illness, then things become a little harder to cope with anyway, and of course, it curtailed his life. It was out of his hands, and that’s the saddest part of the story.

Why do you think Modigliani appeals to people so much?

Lots of us have connected with his art when we were younger. He’s an artist who has been reproduced an awful lot, a lot of us have memories of a poster or of picking up a book about him. He’s very much a part of our visual culture. That itself builds up an immediate connection for many of us.

I think there’s also a human fascination with his story, which is a tragic story. And we’re more compelled to learn more about a person who had a terribly short life, a person whose partner took her own life – there’s a drama to all that. So, these two things, I think.

But there’s also the visual factor, which is the most important. Again, lots of people have tragic lives and leave no mark on the world. There’s something disquieting about these heads by Modigliani, about the eyes he painted, which are sometimes left blank. All these things that keep us fixated…

Cagnes Landscape, 1919. Oil paint on canvas, 460 x 290 mm. Private Collection

And what do you think attracted the forgers?

Very soon after Modigliani passed away, in 1920, the market for his work exploded. His style is very distinctive, and some people thought they could reproduce that. But the interesting thing through all the talk about fakes is that, when it comes to Modigliani, very little technical research has actually been done on his works. As part of this project we encouraged our colleagues at different museums to examine Modigliani’s works in their collections to better understand his methods, and that’s what we’ve been doing ourselves at Tate as well.

There’s also a similar project being done in France.

Yes, the French are doing the same thing. It’s important for museums to look at Modiglianis that are known and accepted and have wonderful provenance, like the ones in our show, to better understand how they were made.

Everything on display in this show is from Ceroni, which is the accepted catalogue raisonné of Modigliani’s artwork (the last version of it was published in the 1970s). Other organisations could try to expand the canon, but, as a public museum, we have a public trust. We had a very conservative view about what we would include in the show.

How does the drama about Modigliani’s work and the fakes challenge your work as a museum curator?

The sad thing about the questions of authenticity that surround Modigliani’s work is that it distracts people from the actual story of the artist. It can sometimes take away the enjoyment of the works themselves. As a museum, we select works very carefully, and we are confident about what we put on display. In a project like ours, the works of art come from very well-respected organisations and from private collections with very strong histories. The controversy around Modigliani tends to relate more to works that have been ‘rediscovered’ and put on the market. It’s a different part of the art world, if you like. That’s why questions about fakes are essentially irrelevant to what we do, because it was not our ambition to try to add new works of art to the canon.

The Little Peasant, c.1918. Medium Oil paint on canvas, 1000 x 645 mm. Tate, presented by Miss Jenny Blaker in memory of Hugh Blaker 1941

Do you think there’s still any chance of coming across a Modigliani at a flea market in Paris?

Perhaps not in a flea market, but works by Modigliani come up at auctions frequently! But, again, auction houses will generally only deal with works that are listed in Ceroni.

And now you’re already working on the next show, right?

That’s the natural rhythm of a curator’s work. You start a project, which is within your walls, while at the same time you’re already thinking about the next one. Which, for me, will be about Picasso, focusing on a single year in his life – 1932. That will open in March.

But it’s been very exciting. There’s something lovely about seeing an exhibition come together, it’s something magical to see works from across the globe all in the same space. It really changes the way you think. You know these works individually, but somehow, when you see them in unison, you start to see the subtlety of colour, the emphasis on drawing in certain areas. You get a deeper understanding of the artist, which would not be possible from a single encounter with one work.

The Modigliani show is on view at Tate Modern till April 2, 2018

* The Government Indemnity Scheme available in the United Kingdom offers an alternative to the cost of commercial insurance, allowing organisations to display art and cultural objects to the public that might not otherwise have been shown due to the high cost of insurance. The scheme provides cost-free indemnity cover to borrowing institutions for loss or damage to art or cultural items on short- or long-term loan. Objects can be intended for public display or study purposes. (from the Arts Council England website)