At the rapid speed of thought

...went the conversation with British artist Jake Chapman in Stockholm

07/03/2016

As I approach the building of the MAGASIN III private museum and exhibition hall, the sky is blue and the sun is shining over Stockholm. It is located in Frihamnen, the former free port of the city, a district where modern apartment blocks and office buildings gradually start to alternate with warehouses and technical structures – until the rows of houses come to an end at the docks; by the way, one of the wharves here is where ferries arriving from Riga moor. I enter the building and take an elevator up; when I come out of it, I find myself in a completely different space. It does not hit me immediately: some 15 – 20 journalists and critics are waiting for the press viewing in the lobby and café – drinking coffee and water and chatting among themselves. And yet it becomes obvious very soon: we are now in the place with the highest concentration of the Chapman Brothers’ art in the whole of Northern Europe.

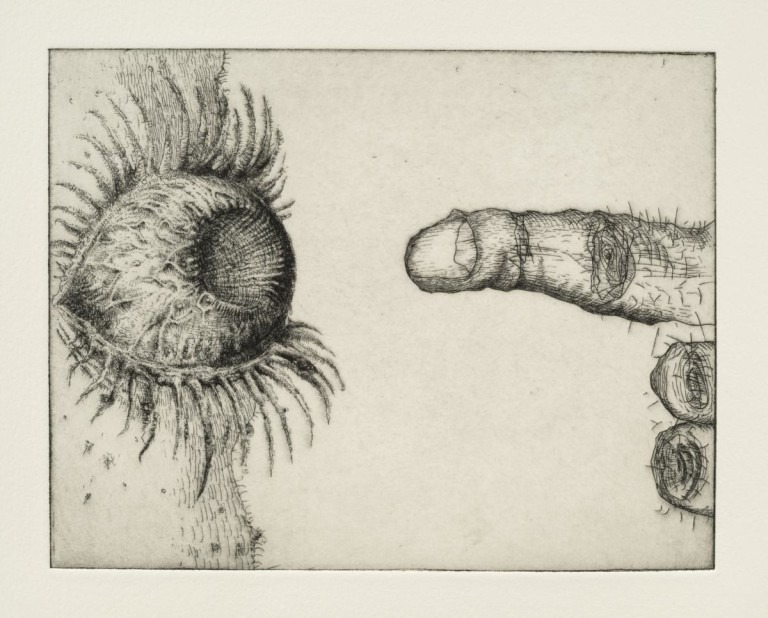

Jake & Dinos Chapman. Disasters of War, 1999. Portfolio of 83 etchings. Paper size: 24,5 x 34,5 cm. Magasin III Collection. Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger

It all started with the still-ongoing exhibition ‘Like a Prayer’ which featured works from Jake and Dinos Chapman’s 1999 series ‘Disasters of War’. Now an extensive show by the Chapman Brothers, entitled ‘The Nature of Particles’, on view through 5 June 2016, has been added to it. It features a selection of works of great diversity: there are sculptures – one of which, ‘Now Eat Your Mind’ (2016), is exhibited in public for the first time – drawings, text objects, installations (including ‘The Sum of All Evil’, thousands and thousands of small figures of torturers and their victims displayed behind glass) and even film: in a separate room, a film by the brothers – ‘The Fucking Hell’ (2013) – is being screened. This part of the exhibition takes the shape of a small cinema with rows of black seats and a film projector; some seats in the front rows are occupied by figures in typical Ku-Klux-Klan robes and conical hats and smiley-face badges; wide-eyed, they are following the goings-on on the screen. These silent spectators, frozen either in shock or delight, wear slippers and bright-coloured knitted socks – Dylanesque, as described by Jake Chapman, one of the authors of the ‘Kino Klub’ installation (2013). The footage loop projected on the screen periodically fills the space with series of screams and howls that accompany Jake’s comments on the exhibition – which, undoubtedly, adds some dark, Gothic and, at the same time, almost comic touch to the whole experience. The older of the two brothers, Dinos, is currently in the USA, and Jake, dressed in an overcoat, jeans and red plaid shirt, is alone here. He is quite tall and speaks not in phrases but in whole speedy passages, making an honest and responsible effort to clarify things that the sophisticated and elegant Tessa Praun, the curator of the exhibition, is asking him about.

Jake & Dinos Chapman. Kino Club, 2013. Photo: Christian Saltas

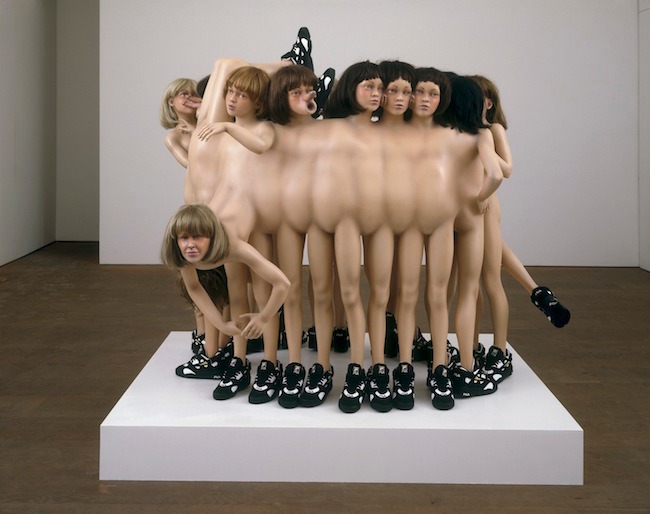

Many years have passed since the time when the world was first shocked by conjoined figures of teenage twin girls with penises instead of noses. The Chapman Brothers are deservedly enjoying the status of two of the most significant figures in the wave called Young British Artists (YBA), to a certain extent – made by the art patron and collector Charles Saatchi who started to pay fantastic – unheard of at the time - sums of money for creations of YBA. The multi-layered character of their works and diversity of media they use (in their own world where nothing is quite what it seems and simple plastic may well turn out to be painted bronze) simultaneously only emphasise the fact that they are focusing on key existential matters. Tessa Praun mentions it, and Jake confirms: ‘I'm not sure if this is necessarily a universal concern of artists, but I think that what we're interested in is returning to the same set of ideas... We're clearly not interested in producing autobiographical work, or work that expresses any sense of personality or identity. In a sense, we've built our own vocabulary of objects. And I guess the best analogy is Samuel Beckett and his notion of stone-sucking, there's this character who has a coat and a number of stones that he places in his pockets and sucks, so he builds this kind of cosmology of meaning through these things by just circulating them. They have no verbal meaning, but they have meaning through their proximity and through this kind of kinetic rotation, so I guess that's kind of what I was trying to explain about art.’

The very room at MAGASIN III that houses the Chapman Brothers’ exhibition also presents a number of works by a completely different artist. It is a loan from Sweden’s Nationalmuseum, twenty etchings from the ‘Los Desastres de la Guerra’ (‘The Disasters of War’) series made by Francisco Goya between 1810 and 1823 and never printed during the artist’s lifetime. Tessa Praun believes that it might be explained by the fact that Spain was probably not the ideal market for these works at the time: after all, the etchings depicted not only the atrocities and violence inflicted upon the Spanish by the French invaders but also the revenge exacted by the Spanish on soldiers of Napoleon’s army. These etchings are considered the first unromanticised images of war. And it was Goya’s etchings that were used as a ‘canvas’ for the rephrasing and deconstruction executed by the Chapman Brothers who put the heads of Ronald McDonalds and Mickey Mouses on some of the figures and mocked and humiliated them in various manners, in a way continuing the same carnage that Goya chose as the subject of his etchings two hundred years ago. The Chapman Brothers’ version became part of the ‘Like a Prayer’ exhibition while Goya’s originals are featured in the new show where they serve as something of a tuning-fork or a winder for everything else on view. Tessa Praun asks Jake about the role played by the figure of the great Spanish artist in the career of the two brothers, and he answers: ‘When we decided to work together, the prospect of two people making work as a collaborative practice led us to consider what content we should be thinking about. Obviously, clearly from an understanding of our history, we considered that Goya would be a good place to start, given that he is conventionally regarded as being the first artist who could be strictly called a modern artist. Which we take to mean: an artist whose activity is based upon internal reflection and, in a sense, an invention of the notion of psychology – as opposed to an artist who is employed to depict the iconographic representations of the Church. Also, this particular set of drawings is very historically revered in terms of their representation of a humanist notion of atrocity – the depiction of man's inhumanity to man. When we started to look at these pictures, we started to think that, maybe there is a degree to which the violence in the images exceeds or surpasses the institutional claims made about their ethical value or their moral value. They're famed for their depiction of man's atrocity and violence, but they seem to be sort of predisposed towards an intensity of pictorial representation of violence. So, we were interested in the degree to which the libidinal content of the work, its economy of a kind of, maybe, surreptitious, negative pessimistic desire, may have historically been misunderstood’.

Francisco Goya. An heroic feat! With dead men! (Grande Hazaña! Con muertos!). Plate 39 from Los Desastres de la Guerra, c. 1810-1823. First edition 1863

The Chapman brothers did more than just reproduce and add to Goya, an act viewed as vandalism by some and as actualisation and returning the works of the great Spanish artist to the contemporary art scene by others. Their piece under the title of ‘Great Deeds Against the Dead’ (1994) is in fact a literal recreation of Plate 36 of Goya’s ‘Disasters of War’ etching series as a markedly naturalistic group of sculptures. In the 1990s, remains of human bodies skewered on a tree might have seemed a ‘burp’ from the past or an exercise in outdated rhetoric, impossible to be repeated again in Europe (although the conflict in Yugoslavia was raging on at the time). However, the quite recent and incredibly brutal clashes in Ukraine have proven to be yet another instance of ‘stepping on the same rake again’, as the saying goes. Violence is difficult to control and it can make people do unthinkable things. The composition of ‘The Sum of All Evil’ represents a whole extensive encyclopaedia of such things: it is thousands and thousands of tiny Plasticine and plastic figures of ‘Satan’s spawn’ in Nazi uniforms, with death-heads instead of faces, torturing thousands and thousands of victims who do not make the slightest attempt to resist. The figures are all approximately the size of a child’s toy soldier. And it is the choice of the seemingly completely unexpected medium of ‘children’s playthings’ for a depiction of various ‘lovely’ aspects of violence and war that Jake is commenting on. However, he invites us, this group of people treading on his heels and following eagerly his every word, to pay attention to a single detail: a frozen (but apparently intended as rolling down one of the little hills) wheel: ‘The meanest, the nastiest, the most brutal and vicious and spiteful and really unnecessarily pessimistic and cynical thing on this whole thing is this wheel (the tyre). It's the worst thing on here because everything else has a purpose in its violence; everything has a connective sort of relation to everything else; everything is equally horrible. But the one thing which is unequally horrible is this tyre that's just rolling off, indifferent to the atrocity that's occurring around it. It also indicates the terms of its kinetic isolation; it demonstrates that all this is occurring in less than a blink of an eye. We're not looking at something which occurs in expanded time. We're just looking at something in terms of its magnitude, that only occurs in the slightest of moments. So, this indicates that this is only a partial representation of a possible atrocity. That's the worst thing there; that's really mean’.

Jake & Dinos Chapman. The Sum of All Evil (detail), 2012-2013. Courtesy White Cube. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

We look at the wheel and then disperse throughout the exhibition, since this was the last object that Jake would comment on. An hour later, we meet again, this time – one on one, at the fantastic library of MAGASIN III. Jake Chapman looks really good against the backdrop of books, and during our conversation he often refers to various books and ideas. I believe that among all the artists I have had the honour to meet, he is the best equipped one intellectually; his thoughts seem to fly as fast as a jet plane and my questions have a hard time keeping up with him – after all, I am busy wrapping my head around all the things Jake has just told. Or perhaps it is his British English that has to take the blame here…

You mentioned that there was a certain moment when you decided to work together; before, you each went your own separate way. What gave you the impetus to work as a team?

It's difficult to give a factual answer to that, really, but I think that some of the artists we were interested in already were working in collaborative practices, such as Art & Language, Fischli Weiss, and Gilbert & George. Quite clearly, the idea of two people working together presents a paradox in terms of the expectation of what artists do. The presumption is that a work of art is a truthful object made by a single person, and its truthfulness has something to do with the artist being confessional and sincere in his practice. The idea of two people working together automatically introduces a question of doubt about the authenticity of the work, because if a work of art has to do with a spontaneous expression of ideas, this then refers to a singularity. Two people minimizes the spontaneity of the work; it means that the work originates from a conversation, and it is perceived as being perhaps more coercive. That was the attraction of working together – that we could ruin the notion that the work had authenticity. As though we were ganging-up on the viewer.

With brothers working together, is there an issue of competition? Or conflict over who does what?

No; I think that the only way in which our genetic relationship had any influence over our working together was because we were used to talking to each other about art and ideas. When we work, we don't have a symbiotic relationship in terms of a closeness that has something to do with being brothers, but we also don't have a hostility which can be characteristic of brothers. We work because we like each other's ideas. We don't socialize. Our working relationship is peculiar in as much as there's no methodology to it; I just like his ideas. When we work, it's not as if we are literally working with four hands on one object. We work separately, and then we overlap, and then we change each other's stuff.

Dinos worked with Gilbert & George for seven years (I did for one), and our experience working with them was that we saw that they wanted to make work that was reflective of both of them equally. They call it democratic. They make symbiotic work. Our work is anything but that.

Portrait Dinos and Jake Chapman in their studio, 2013. Photo: Nic Serpell Rand

Since you both have the same background, maybe it's just that you understand each other much better...?

Yeah, that's fair enough. We made a show called “Jake or Dinos Chapman”, and we spent a year working separately in two different studios. And the presumption would be that if we work separately, that maybe a more autobiographical element might somehow surreptitiously find its way in, and maybe my work would become more soft, and Dinos' work would become more soft, more personal, more humane. But in actual fact, when we revealed the work and put the work in the gallery, it was pretty much the same. You know, we're reading the same books, we're thinking about the same ideas, so it's inevitable that those ideas aggregate in a particular way. It's very unlikely that I was going to do watercolors and seascapes, and he was going to paint flowers.

Maybe the personal, familiar background is not so important in your case – it seems that the keyword here is ideas. I was reading one of your interviews in which you said that an artist doesn't have to bring into his art just the things that he knows personally.

Best not. Quite the opposite, I think.

So, it's more like "philosophical art"?

It's not everyone's choice for how they make art, but I'm really not interested in art that has a personal perspective to it. I find it really just dull. That's not just a stylistic difference; I'm actually aggressively against it because one of the potentials in making art is that it eradicates the notion of identity.

When you look at a Rothko or Pollock painting, it's an absurdity to think about Mark Rothko or to think about Jackson Pollock. If you see the paintings, you see the paintings as material objects that are connected to other material objects. You don't have to negotiate the work by knowing what Mark Rothko had for tea, or whether Jackson Pollock killed himself in a car. It makes no difference to the work. Although, certainly there are art histories that dictate that the personality is essential to the effect of the work. I'm saying the opposite. And I think the idea of working together is a way of increasing the difficulty in reducing the work to the people who made it. If there's two of them, maybe even more, then you can't reduce it to personalities. If there's too many people making the work, then all you're left with is the work.

Jake & Dinos Chapman. Not to Dot, 2013 (detail). Photo: Photo Jack Hems / Courtesy White Cube

That would be a controversial idea for those who think that an artist is constructing something from personal impressions.

If you're a plumber, you’re job is to fix the flow between where the water starts and where it ends. It's a linear process... The thing about being an artist is, you can go to the studio and say, “Today, I'm going to make a painting about plumbing,” – basically, make “something” which means “this”. So, you start with the intentions of pursuing this end result, which is your idea, an expression of your personality maybe... you know, how you think this thing will reflect you.

The thing is, when you make a work of art, quite soon you realize that a work of art doesn't function in that way. It doesn't function in such a closed way. When you approach making work in a closed way, in terms of expecting it to have some fidelity with what your expectations are, it becomes something else. So, more than anything – more than plumbing, more than science, more than driving a car – when you make a work of art, it disinherits the intention. The irony being that when a plumber goes to fix your plumbing, they don't want it to be anything else than plumbing; or when you drive a car, it's nothing else than driving a car. There are no greater intentions, there are no greater artistic intentions about either of these things. But the irony being that the one thing which is culturally determined to be an exemplar of intentions, is actually the one thing that says less about the person than the plumbing and the driving. Because if I say that I'm going to paint a picture that means “this”, then the outcome is something completely different. Well, that's even less than what the plumber did, and it's less than what the person who is driving did; because if the plumber doesn't do plumbing, then it's not plumbing. These things have an integrity, an autonomy within them which is not based upon exterior or inflated intentions. Because when artists have intentions, the primary rule of a work of art is to undermine the authority of their involvement. So, the artist's personality is merely shat out onto the floor, you know? There's no point in pursuing the notion that a work of art will have any kind of identitarian allegiance. Because in effect, the idea of making a work of art is an open-ended system, not a closed system, and the open-endedness of it means to say that you are the primary victim of its process.

Does this mean that, at some point, you have to step from personal to impersonal?

I'm taking an extreme materialist point of view. Prior to even when the artist decides to make a painting – when does the expression of the artist's personality come in? Is it when they go buy the brushes and the paint and the canvas and the stretcher and then they start painting? Because the thing is, already in the activating of resources to make the painting, you've made decisions which are impersonal. So, what happens as the impersonal begins? So you already know you're going to make a painting, and that's an impersonal choice. Everyone knows what a painting is, you haven't made anything different from any other painting until you actually start to make the painting. Now, invariably, when you make a painting, you'll be thinking of other paintings; you'll be thinking of the works that are familiar to you in terms of the history of art. You're not going to be able to – not in a billion years – make a painting that has no relation to no other paintings. So already, the chances of any kind of personal sort of intervention into the process of making art is not looking good.

Jake and Dinos Chapman. Now Eat Your Mind, 2016. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Christian Saltas

So, you should find your own kind of strategy?

Well, it's about language, really; it's more about language than anything to do with self-expression. Language and self-expression are not the same, you know; they're not. You mentioned philosophy; Heidegger reversed the assumption that “man speaks language”, suggesting instead that “language speaks man”. That language already has a set of compulsions, a momentum, and a dynamic that precedes our use of it. So that it has value; all of the words we use have implicit value before we use them. We don't use language as an instrument of our use; we are not in control of language. We can contort language and make it mean what we want; in effect, language has it own meaning before we borrow it. So, in the same way, when you make a painting, you're only borrowing the language, to reduce this to the remote chance of a specialized expression is less than idiotic.

Do the subjects of your work change under the influence of time – under the influence of what's going on in the world around you?

I think it must, although it appears to me to be rather similar [chuckles]. When you see our work, you see almost a language of limited components... The idea that, after a while, the work begins making its own work. The associations of how things work seems to suggest themselves from the vocabulary of the work itself rather than from us just simply assuming that we can just say things. I think Samuel Beckett’s “stone-sucking”, is a good example of what we do. He forms a dynamic language from circulating and sucking a number of stones from each pocket in his coat. The language is non-verbal and serves no instrumental purpose – it does not represent anything other than itself. It presents a cosmological variation of a language, but doesn't have anything to do with anything other than its own function.

You mentioned language, which reminds me a bit of what my colleagues and I do – we make something that lies between poetry and the visual arts. We built a poem not from language, but from things; we tried to get a message across through objects.

Art is an analog for something, but when the thing becomes itself, then it's no longer an analog. Then you can say that it's no longer art. When a toilet finds its way into a gallery, it is no longer itself – it is no longer a toilet, but a representation of the toilet itself. Then you have nothing which is in excess or in surplus to the object. The death of language. No more analog, no more metaphor.

Late modernist writers got rid of the word “like” because the function of literature was to say things such as: “the sea was like an undulating piece of fabric”, or, “the sun loomed in the sky like a light bulb”; things in the world are like other things. Literature's job is to make analogies, to make comparative judgments so that when you look at the sun you think “sun”, but when you look at a poem or a painting, you think of it in a poetic way. What analogy does, and what metaphor does, is it produces the poetry that the makes the things in the world better than themselves. But if you get rid of the poetry, get rid of the analog, all you have is the sun; you have no poetry. Which is probably a good thing [laughs].

Jake and Dinos Chapman. Zygotic Acceleration, Biogenetic, De-Sublimated Libidinal Model (Enlarged x 1000), 1995

When people describe your works and their impressions of them, they often use two words: “humor” and “horror”. The two words actually start with the same letter – kind of like brothers in some sense. Would you say that these words are accurate?

They can be used as journalistic shorthand for not really looking at the work; for not doing the job that you're supposed to be doing when you're looking at art. As if we look at art and just think about the most facile thing that occurs in your experience of it...

It's more “humor” than “horror” [chuckles]. The work is funnier that it is horrible. But humor and horror are kind of indiscernible, aren't they? I suppose the most common experience in relation to things that are horrible is laughter. Laughter is a non-verbal response to something that is unintelligible and where there are no means in describing it. Laughter is like death, like a non-linguistic, guttural sort of outburst. The problem is that once certain words have been nailed into the works so thoroughly, you get this repetitive regurgitation of the same criticism over and over again. It's not only lazy, but it's like – today some journalists just came over and said – Why do I have to look at this stuff? Why do I have to look at things that are horrible? And I said – Isn't it the truth that an artist is supposed to reflect upon the conditions of their experience – of my experience – on all this?

You know, you can go to Montmartre in Paris and watch these painters who have set up their little easels and they're painting the Sacré Cœur across the road, with a blur of cars zooming by in fucking four lanes of traffic. But in every little painting, there's the foreground, some people, and then the Sacré Cœur – but no fucking cars. So, their version of their condition of experience has something to do with the denial of reality.

Why should I look at something I don't want to? – [the journalist] says. Well, [the journalist] presumes she wants to look at pretty flowers and puppies. And I said – Christ, you can look at that kind of stuff every day...

It's a strange thing to say: Why should art make me look at things I don't want to? I could ask [the journalist]: So, you have something on your TV that filters out images you don't want to look at?

I find it very strange...

Fragment from 'The Almighty Disappointment'. 2011. Photo: cranetvart

I was quite impressed by what you said today at the exhibition. You were talking about what experience actually means nowadays. OK, we are not at the war physically, but we are looking at it with our own eyes – in the news...

It's interesting, considering the amount of violence we see every day, and yet we tell ourselves we see nothing. There's this paradox in that we are at odds with the forms of representation that we do see as real. We limit the sense in which our reality is real to us. Like when Goya says, “I saw this”, but he didn’t necessarily see it – the reason those pieces are so notoriously offensive, by our institutions of morality, is that they think that the value of the work has something to do with the actual experience of seeing it... If you introduced the notion that these works were produced without the direct authority of lived experience, would it undermine the work? Would people start to take the “Disasters of War” off the walls of the Prado because he didn't actually see them? Smashing them because he didn't actually see them – would it make the work any less good? In terms of violence, we've probably seen more violence than Goya ever saw because we have access to images of people being beheaded on the internet. We can watch infinite series of violence; there's no limit because it's not “in the flesh”. Does that make it less real? […] Why would it be that our experience of violence isn't real?

Jake & Dinos Chapman. The Sum of All Evil (detail), 2012-2013. Photo: Todd White Art Photography / Courtesy White Cube

Maybe we should rethink what reality is?

Yeah, absolutely.

People who play violent computer games say it isn't reality, but it is.

Yes, of course, it is reality. It's just that it's virtual. It's as real as anything else.

Foucault's “The History of Sexuality” undermines the presumption about Victorian repression – he illustrates the point by referring to the curtains made for piano legs because their ‘nakedness’ was deemed “rude” – but rather than this concealment being an index or a phobia for sex, it demonstrated that they saw sex in everything. Rather than being oppressed, everything was surreptitiously sexualized. Rather than Victorian morality denying the reality of sex, it heightened its reality by producing a libidinal economy that permeated all things – that the act of sex, the mere animal act was thus refined as a component of voyeurism – where direct sexual pleasure was supplanted by looking.

So, we lead our lives under the impression that we are remote from images of violence, that our experience of watching horror films and playing games is a symptom of our being remote from direct violence, vis-à-vis Foucault’s Victorians, we are surrounded by violence and absolutely immersed in it. The question of what counts as real is partly a suppression of the notion of what we call real. How closer to the act of bombing can we be than for the camera to be positioned on the front of a missile? I mean, it couldn't be more real.

Jake & Dinos Chapman. The Sum of All Evil (detail), 2012-2013. Courtesy White Cube. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Another thing I'd like to bring up, in addition to violence and war, is money. You and Dinos drew caricatures on currency notes at the Frieze art fair, which was a rather interesting act in that you were simultaneously “ruining” these things, while also adding a “super-value” to them.

Yes, there was a confusing dynamic there [chuckles]. I think our defense in court could be something like – look, the state has a finite amount of money, so would could be sentenced or punished for drawing on money – this is because we are reducing the amount of money available. But one could argue that by destroying money in favor of making it more scare, we are also increasing its value. A super-powered economy based on vandalism...

It was an interesting idea. It was quite funny; you could see all these people queuing up with a gluttonous interest, thinking: “Fuck, this is great! I give them some money, they draw on it and give it back to me – it's like money for nothing!” And you see them going through their pockets – now this is really funny – and they pull out a 10£ note, a 20£ note, and a 50£ note. They look at the 50 and think – Oh, no... – and stick it back in their pocket. And you think – You fucking idiot, do you honestly think that there's a relative scale of value? 50£ is too much to give to draw on because you think what? Suddenly you’re calculating the relation between the value of literal money and our drawing – and your calculations suggest you'd rather give me a £10... [Chuckles]. It's absolutely brilliant, genius – this power of thinking... But the intrinsic value of the currency is now meaningless... once it's drawn on its State value is meaningless... it's not going to be worth the value of the drawing plus 50£! [Chuckles].

Isn't that a model that art can use nowadays – destroying something, rewriting, remaking something in a strange way...?

That's pretty much the function of art anyway. The perception of how to make a work of art is predicated upon your perception of what happened before it. I don't know if it's necessarily a work of art when people in therapy are making drawings with crayons about how they feel. I think when you make a work of art, it has something to do with overlapping and stepping on something that's happened before. There's a destructive imperative to making a work of art, which is probably simultaneous with a creative component.

In terms of the drawing on money project (and I only found this out recently), the British suffragettes used to stamp on coins [the slogan] “Votes for women”, and they returned them back into circulation – infiltrating a currency that can't be taken out of currency, so the act of buying something is simultaneously a political act. If you're a person who gets stuck with a suffragette coin, you're going to invariably try and give it to someone else, because you don't want to be the one person left with it who can't use it. So, you're thinking even more about what it means. That was great, really good...

Jake & Dinos Chapman. Not to Dot, 2013 (detail). Photo: Photo Jack Hems / Courtesy White Cube

You earlier spoke about “value” and “super-value” – what is the value in something today when you can see everything from ten different angles, you have information from ten different points? What, right now, is most valuable to you?

I don't know about value... What about the idea of turning off the internet for a year? That would be a good idea. Just do it randomly, even for a month. The problem with infinite distribution in every direction, is that there is no core to entropy – nothing matters [chuckles]; a cold dark universe, but surveilled to an inch of its life.

If I were younger and more intelligent, I'd probably want to be a hacker. I think that's probably the only thing that would be worthwhile doing right now. To enter the code, go inside the code, inside the death drive. I think that would be the only interesting thing to do; being outside the code doesn't matter. And what happens if art just grinds to a halt? Becomes saturated by global interests and distribution until it becomes tired and jaded and spent? It's like saying – Can you imagine in fifty the years' time the end of humor? That people don't laugh anymore? Or no more crying?

Did the ancient Greeks get bored? Will boredom be a thing that humans continue to do in the future?

Maybe in the future people will say – Do you remember that funny sound that came out of your mouth that wasn't words? No, I don't known what you're talking about... – There will be archeologists of humor, historians of humor claiming that there used to be a time when people made this sound: Ha ha ha. People might think what they’re saying is ridiculous, but they wouldn’t laugh at them because they wouldn't know what that was.

So maybe there's an end to art and humor – new civilizations that live without art or laughter, cultures that employ historians to explain what it was and what its purpose was.

As long as people are still able to feel fear, they will also laugh at these things. I think that, somehow, it's connected.

If all goes well with artificial intelligence, we can just plug in and you won't need to be with anyone else. You won't need to laugh... because laughter is under-confidence escaping imperfect bodies, or fear; it's only something that you show in front of other people. Its an appeal against pain.

But then you could become afraid of yourself! [laughs]

[Laughs] Or, there could be a future where there is only laughing, no seriousness. There was once celestial alchemy, and that's gone. There used to be classical music, and that's pretty much gone. There used to be a God… These things were absolute values. The Greeks didn't think that Greek tragedy would disappear. And now we've got opera… Nobody goes to opera; people only go to opera because they want to harmonize with an aristocratic concept of the sublime – either that or to laugh and mock it. Our pathos in insincere, the sort of experiential feeling that people used to have, say, like the ancient Greeks had; when someone was stabbed on stage, everyone felt stabbed. Empathy wasn't acted-out, triggered by representation, it was actual. These things which we take to be transcendent and everlasting – like laughter, or art, or literature – will end. What a great idea, don't you think? We should end it on that [laughs]!