‘Sometimes when I wake up, I don’t remember where I am’

19/03/2018

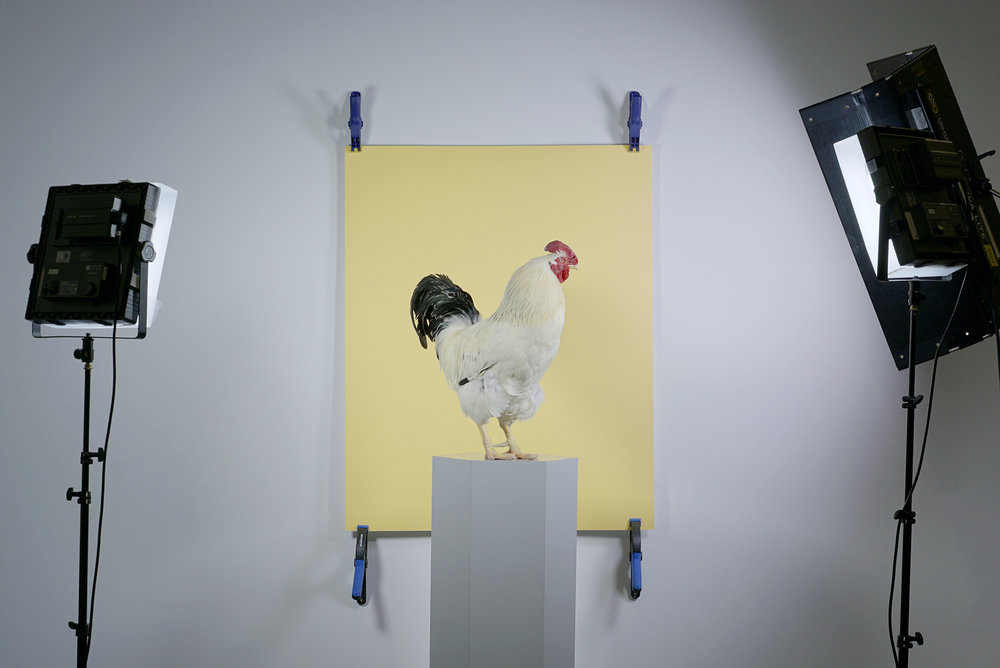

Фрагмент экспозиции «From a body I spent». Фото: Виктория Экста

Мы встречаемся с Феликсом в kim?, вместе с куратором его выставки, гречанкой Майей Тоунта присаживаемся прямо на той же деревянной конструкции и готовимся к беседе, вооружившись большими чашками с мятным чаем. Я вручаю Феликсу подарок – только что изданную книгу фотографий Владимира Светлова «Rīgas Līcis», посвящённую одноимённому санаторию, работавшему до 2003 года в Юрмале, а теперь давно законсервированному. Феликс листает её, и этот визуальный сюжет оказывается ему близок и вызывает в ответ собственную историю…

– Моя бабушка выросла в подобном санатории на берегу Финского залива, её отец там был директором. Это был Дом творчества, и там жили разные художники и музыканты. Она была очень хороша собой, и тамошние «творцы» вдохновлялись ей, рисовали её и сочиняли для неё музыку. А она была как муза этого места, собиравшая мужские сердца на своих прогулках.

А ваши родители из Петербурга?

Мой отец оттуда, а мама родилась в Эстонии и жила в Таллине, пока не решила уехать и получить медицинское образование. Её родители родом из Беларуси, а по линии отца моя бабушка наполовину армянка, наполовину русская, а дед – из Украины. Поэтому в своём эссе, которое я прочитал вслух в начале перформанса, я называю себя soviet, потому что считаю себя продуктом свойственного той эпохе смешения людей и их географий.

А в Канаду вы переехали из Петербурга?

Нет, из Израиля.

То есть ваша семья сначала направилась туда?

Когда открыли границы в 1989-м, многие евреи стали уезжать. И мы сначала решили отправиться в Израиль. В то время многие так делали – из-за того, что не было прямого рейса в Израиль, люди летели через Рим или Вену. А в Риме они объявляли, что не собираются лететь дальше в Израиль…

Prelude. 2016. Кадр из видео

Что планы поменялись…

Да, и что они хотят попросить статус беженца в США, и тогда их оставляли в Риме до выяснения их судьбы. Это даже называлось тогда «римские каникулы» – по одноимённому фильму. Они там ждали месяц или около того, пока будут оформлены необходимые бумаги, и потом отправлялись в Америку. Но мы были среди тех идиотов, которые ничего не поменяли и полетели в Израиль. Окружающие были в ужасе: «Зачем вы туда летите? Отправляйтесь в США!» Но у моих родителей были родственники там, которые эмигрировали в 1970-е. И они писали нам, что всё классно, что можно легко найти работу, что очень много возможностей. А потом выяснилось, что им было просто скучно, им хотелось компании и в каком-то смысле они нас надурили. Когда мы оказались в Израиле, то началось – война в заливе, интифада. А израильские власти к эмигрантам из СССР относились как к людям второго сорта. Просто как к рабочей силе и телам, которые должны действовать в приграничной полосе. Нас поселили совсем не в классной квартире в Тель-Авиве, а на границе…

И тогда ваша семья решила отправиться в Канаду.

Да, в декабре 1993 года.

Сколько вам было лет?

Шесть с половиной.

Трейлер видеоработы «House of Skin» (2016)

Что-то помните из этого времени?

Да, и довольно много. Правда, об Израиле у меня довольно мифологические воспоминания. Что-то наподобие первого спуска с холма на двухколёсном велосипеде. И падения во время него. Но, конечно, ещё – ракетные обстрелы, газ… В своём видео «House of Skin» я посещаю все эти места, где мы жили, с помощью опции street view на Google Earth. И пытаюсь увидеть их. Потому что в то время я не мог вернуться ни в Россию, ни в Израиль (в котором меня бы посадили в тюрьму за то, что я не пошёл в армию). И я решил посетить эти места виртуально. Я пытался найти эти места по своим воспоминаниям, по тому, как я запомнил окружающие фрагменты реальности. Так я нашёл дом, где, как мне казалось, была наша израильская квартира, и показал маме. Она была поражена: «Как же ты это запомнил?» Я же был такой маленький, когда мы уехали. А она помогла мне найти наш дом, в котором мы жили в Ленинграде. Но потом оказалось, что всё-таки это не та квартира и не тот дом. У мамы не очень хорошо с географией и координатами. Потом уже, когда я работал над видео «Neither Country, Nor Graveyard» и отправился в Петербург, я обратился к отцу, и вот он послал мне точные координаты – нашего дома, места, где он работал, где работала мама. Это ведь был его город – город, в котором он родился и вырос. Так что выяснилось, что дом совсем в другом месте, эта была пятиэтажка на окраине, но я оставил в «House of Skin» всё как есть, мне казалось, что это очень интересно – этот разрыв между реальностью и нашими воспоминаниями.

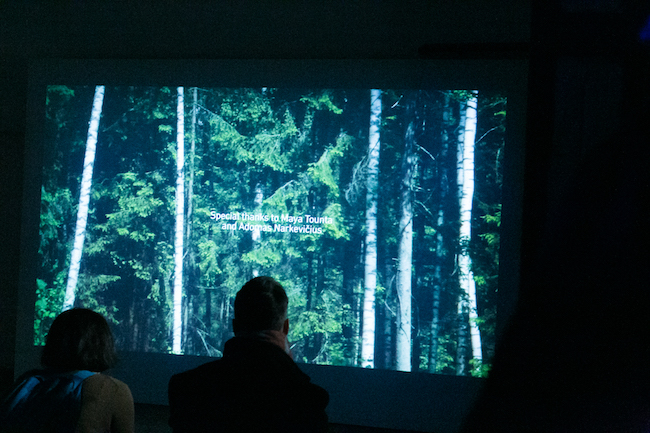

В «Neither Country, Nor Graveyard» есть съёмки Петербурга (тогда ещё Ленинграда) 1989 года, которые вы совмещаете в одной видеоплоскости с кадрами, что сделали сами в тех же местах. Но кто снимал тогда, в самом конце 1980-х? Там очень профессионально всё выглядит – дальние планы, камера не дрожит.

Это был специально нанятый видеооператор. В то время видеокамеры были редкостью в советской действительности. Мой отец рассказывал, что он знал всего одного такого человека, и он отдал ему свою месячную зарплату за эту съёмку. Но он сделал это и потому, что когда вы эмигрировали, по существующим законам вы не могли взять с собой все свои деньги. Папа говорил, что можно было вывозить что-то вроде ста долларов на человека. И тогда он вложил деньги в воспоминания.

Ни страны, ни погоста / Neither Country, Nor Graveyard. 2017

Он попросил видеооператора снять не только свою семью, но и сам город.

Именно. И это в общем-то странно с точки зрения «документа» – там нет съёмок нашей квартиры, нет съёмок нашего района. Там в основном очень туристические места. Любой, кто приезжал в Петербург хотя бы на день, их узнает. И мои родители как будто изображали туристов в своём родном городе – бродили среди парков и памятников

Когда я вернулся туда через 27 лет, то не помнил уже ни одного из этих мест. Поэтому и оказался туристом в городе, в котором когда-то родился. И вот такой «люфт» между двумя этими развёрнутыми во времени «туристическими» прогулками показался мне интересным.

Существует какая-то очень интимная связь человека с пейзажем. Я помню, что оказался в Риге ещё до того, как вернулся в Россию, и вот я как-то шёл по Каменному мосту через Даугаву, который ведёт теперь от Старого города к Национальной библиотеке. Он мне напомнил один из петербургских мостов, и когда я шагал по нему, у меня появилось очень странное чувство в груди, что-то вроде приступа невероятной меланхолии и ощущения дежавю.

Я думаю, что воспоминания о событиях и местах откладываются в нас и на генетическом уровне. Когда я приехал в Вильнюс – в арт-резиденцию Rupert, – я взял такси, чтобы доехать из аэропорта в это место, и там надо было ехать через лес, сосновый лес. И у меня тоже возникло это странное ощущение – как будто я когда-то множество раз плакал в этом лесу или что-то в этом роде. Я не понимал, что это. Но такие вещи можно объяснить генетически. Кстати, моя мама – генетик, она работает в этой сфере и сейчас.

По мере того, как мы проживаем нашу жизнь, в нас есть наш генетический код, генетический набор, который либо деградирует, либо, наоборот, пополняется за счёт того, что мы переживаем. И чем больше травматического опыта в жизни, конфликтов, тем больше на нём «отпечатков». Раньше думали, что при рождении ребёнка это всё «обнуляется», но оказывается, что как раз самые болезненные и травматичные отметки передаются дальше, будущим поколениям.

Есть исследования о том, как повлиял в этом смысле Холокост, это связывают со случаями и самоубийств, и депрессий, и сердечных проблем. Ведь когда ты испытываешь стресс или депрессию, первым делом это влияет на сердце. Но всё это далеко не только еврейская проблема. Есть исследования на эту тему, связанные с расовым опытом, геттоизацией чернокожего населения Америки. И они меняют то, как мы привыкли смотреть на эгалитарное общество, общество разных возможностей. Оказывается, мы должны учитывать прошлое наших предков, мы не можем его стереть, сбросить со счетов. Оно непосредственно влияет на наше физическое и психическое здоровье.

Growths. 2012. Видеоработа является результатом нескольких месяцев размножения плесени на 35-мм киноплёнке голливудских трейлеров прошлого десятилетия

Кажется, ваши тогдашние ощущения от леса вылились в вашу работу прошлого года «The Taste of Real Bread», основанную на фрагменте воспоминаний женщины, Фани Бранцовской, пережившей Холокост и ставшей партизанкой как раз в подобном литовском лесу всего в 40 км от Вильнюса?

Да, я проводил тогда в Литве свои исследования по теме Бунда, Холокоста и мест массовых убийств в лесах. В тех же лесах, которые позднее стали и укрытием для избежавших бойни еврейских партизан. Лес оказался как будто живым свидетелем всех этих историй. И то, как лес взаимодействует со светом… мне иногда кажется, что он «играет», «представляет» нам что-то. Тут многое можно сказать и без слов. Когда огромное облако наплывает, и всё погружается во тьму, а потом оно уходит, и наступает момент почти откровения, прозрачности. Лес тут выступает рассказчиком в каком-то смысле.

В этом видео лес действительно прекрасен. Он выглядит совсем не мрачным и абсолютно живым…

Да, безусловно.

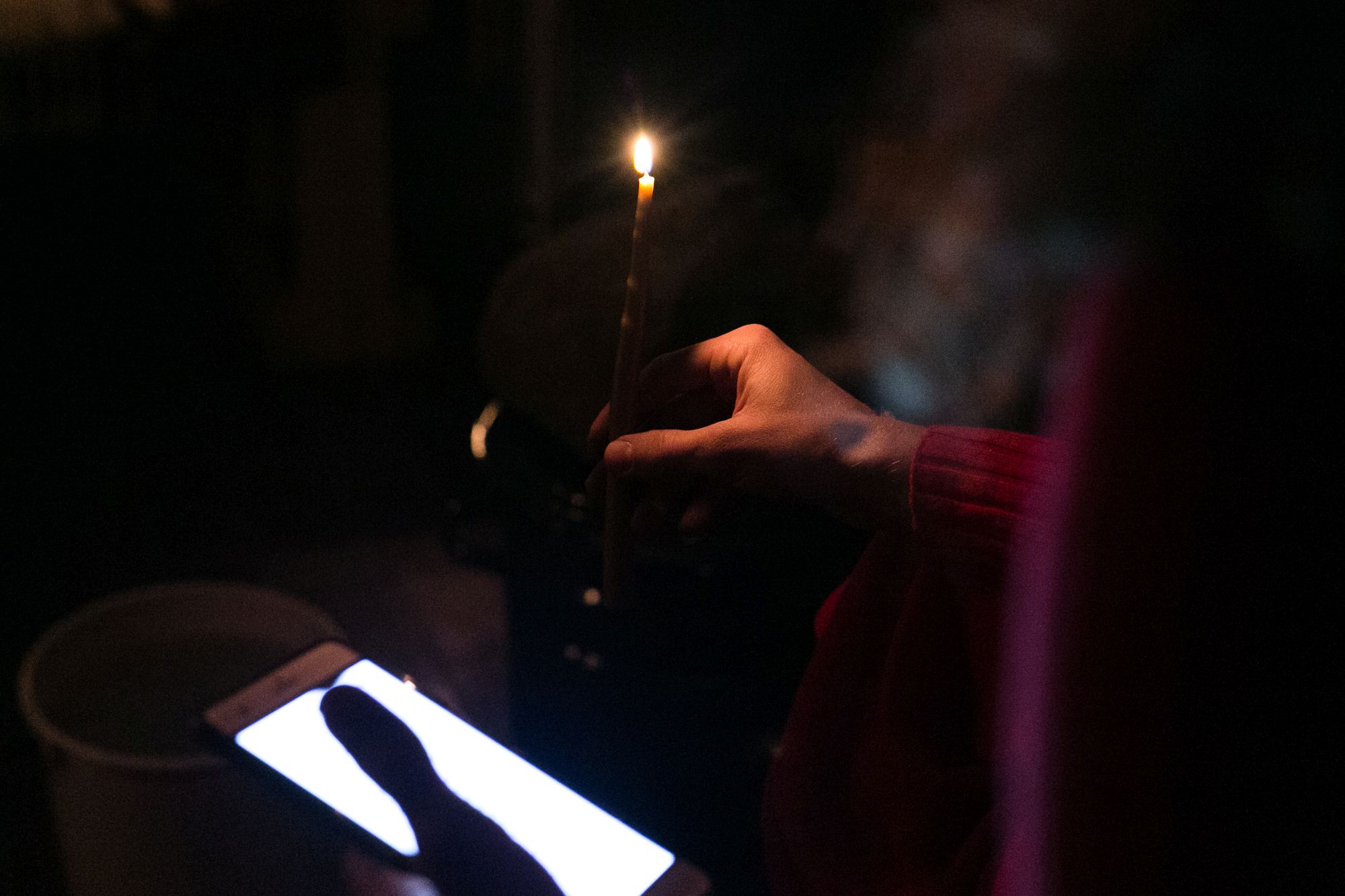

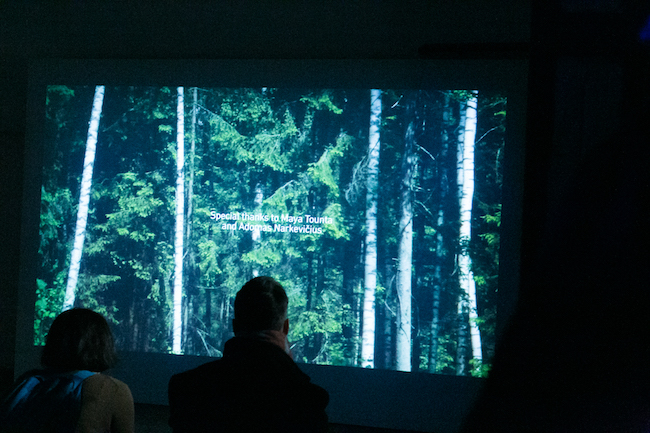

Зрители у работы «The Taste of Real Bread» в kim? в феврале 2018-го. Фото: Виктория Экста

А когда вы выражаете, концентрируете какие-то свои воспоминания в работах, как они меняются в вам самом? Они перестают беспокоить или…

В каком-то смысле это терапия. Это как разговор с психоаналитиком, который помогает поднять на поверхность ваши важные воспоминания. «House of Skin», например, я делал в то время, когда сам вступил в конфронтацию со своими внутренними проблемами – это и травма ракетного обстрела в Израиле, травма сексуального насилия, пережитого в моей собственной семье, травма двойной эмиграции – я ощущал всё это очень тяжело в себе самом. И понял, что лучший способ справиться с этим – это пройти через это насквозь, пройти и выйти.

У меня есть любимая фраза I learn by going, я часто повторяю её себе, особенно когда чувствую себя одиноким или потерянным во время своих путешествий. И я решил «пройти» всё это, используя «машинное видение» Google, или визуальный опыт других людей, загружающих свои ролики в Yotube, или семейные фотографии, которые есть у меня самого. Запустить в себя все эти голоса и прийти к какому-то осознанию. Когда я монтировал, это был очень непростой опыт, сам монтаж занял у меня месяцы. Я вообще-то не из тех, у кого глаза на мокром месте, и обычно я плачу только в кино в какие-нибудь моменты проявления прекрасной гуманности. Но тут слёзы подкатывали каждую неделю. Я ревел от печали. Но это и была та терапия, которой я избегал в своей жизни до этого момента. Потом уже мне было сложно показывать этот фильм другим или вообще решить, что он окончен, готов. Я его «редактировал» и переделывал почти два года. Но в конце концов всё это привело к какому-то согласию во мне самом, это не решило проблемы навсегда, но они уже больше не могли довести меня до слёз.

Вы поставили это на своё место, на какую-то полку в своём сознании.

Именно. И то же самое было с фильмом о лесе. Я был настолько же захвачен всем этим материалом – этим невероятным уровнем насилия – и тем, как позднее всё это стало предметом политической торговли. И не только со стороны литовского правительства, но и со стороны местной еврейской общины в Вильнюсе. Потому что есть две еврейские общины на самом деле, одна – инкорпорированная в современное состояние дел, в сделки по имуществу или по бизнесу, а другая – это выжившие, и у них совсем другое понимание сути проблемы: всё, чего они хотят, – это справедливость.

Интересно, что в вашем искусстве довольно большую роль играет конфликт – и внутренний, и внешний. Хотя вы сами не производите впечатления конфликтного человека.

Нет, я очень мирный человек. По крайней мере, пока могу выспаться и получить кофе на завтрак.

Fountain. 2015. Пейзажная инсталляция с садовым фонтаном, работающим на солнечной энергии на верхушке бархана в пустыне Сахара

Но вот, например, входящих в kim? сейчас встречает ваша работа «Highway 80», посвящённая эпизоду войны 1991 года в Персидском заливе – атаке объединённых американских и канадских сил на солдат отступающей из Кувейта иракской армии и двигающихся с ними палестинцев.

Эта работа – попытка воспрепятствовать замалчиванию этого эпизода, который многими воспринимается как военное преступление. И как момент, который повысил уровень насилия и жертв на Ближнем Востоке. Я чувствую моральную обязанность как человек, от чьего имени в том числе действовали победоносные «западные» войска, не позволить этому всплеску насилия быть забытым.

Да, всё это произошло более 20 лет назад. Но мы не можем понять современный кризис с беженцами из Сирии и Ирака без понимания войны в заливе и без знания постколониальной истории этого региона. Ещё не так давно ИГИЛ постоянно подчёркивал несправедливость тех соглашений, которые западные державы заключили после окончания Первой мировой войны и распада Оттоманской империи, и видел в этом обоснование идеи создания Исламского государства на тех территориях. Да, это было для них лишь теоретической базой для нового витка насилия. Но мы всё равно не можем распутать весь узел противоречий в этом регионе без осознания того, что произошло 100 лет назад.

Я вижу такие вещи как этическое обязательство для каждого. Это непросто, но без осознания прошлого движение к чему-то позитивному в будущем невозможно. Помните этот оптимизм 1990-х, этот «конец истории» и всеобщую радость по этому поводу? Почему тема Холокоста оказалась такой трудной для Литвы в это же самое время? Потому что было ощущение – мы прошли тяжкий период, советский период, мы двигаемся к свободному и лёгкому либеральному капитализму, каждый сможет быть тем, кем он захочет. И все теперь равны, у всех одинаковый выход на международный рынок. Они не хотели в том момент углубляться в историю. Но вы не можете избежать этого, вы можете лишь делать вид, что она кончилась, её больше нет, но история никуда не денется.

Она, скажем, будет жить в памяти старшего поколения, и это и есть одна из причин, почему старшее поколение так настойчиво пытаются «отодвинуть» от молодёжи, от того, каким путём движутся сейчас страны. А на это старшее поколение реагирует в свойственной ему манере – выходит на демонстрации под советскими флагами или под националистическими лозунгами. Они боятся полного «стирания» их опыта, забвения того, что они пережили. И вы можете увидеть это в самых разных странах.

Люди, которые прожили всю эту историю в своих жизнях, знают, насколько она теперь «урезана», реорганизована. Солдат Иракской национальной гвардии, чьё свидетельство используется в «Highway 80», знает другую сторону истории. Фаня Бранцовская, которой довелось жить при четырёх разных режимах, польском, немецком, советском и литовском, знает об этом даже слишком много. Она была свидетелем того, что государство – это не стабильный концепт, это хрупкая сущность, которая может пережить коллапс так же легко, как какая-то корпорация, как какое-то общество, семья или индивидуум.

Собирая эти свидетельства, собирая эти судьбы, мы выступаем в роли своего рода «спасателей» истории – мы не хотим, чтобы нашу историю забрали от нас, редуцировали до уровня, который кому-то выгоднее. Заботясь об этом знании, мы становимся преградой на пути возникновения новых фашистских, националистических государственных формаций. И это знание можно потерять, если к истории будут подходить упрощённо.

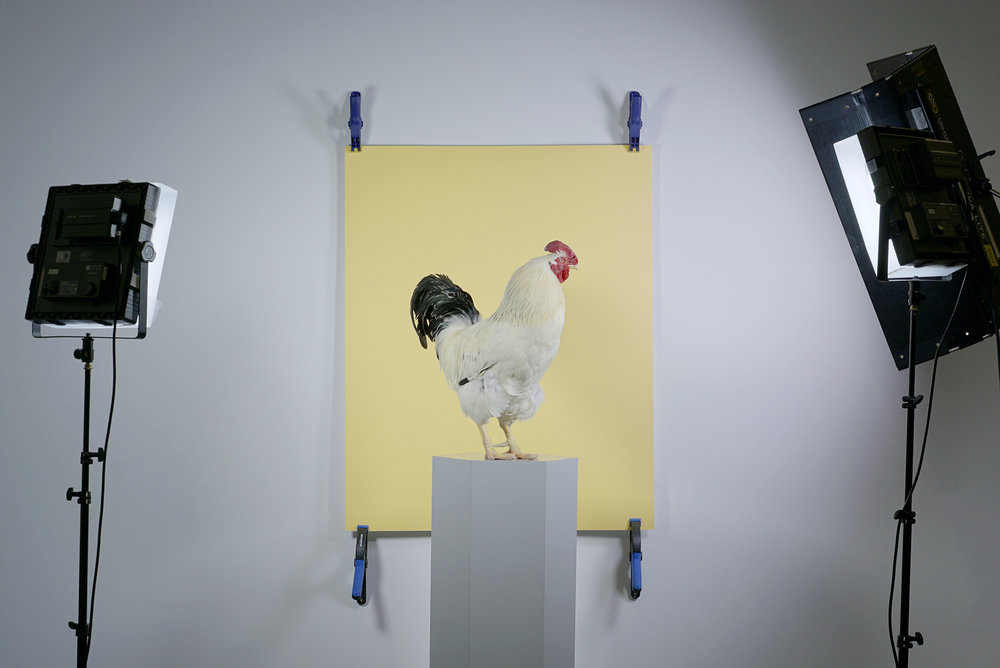

Фрагменты перформанса Феликса Калменсона на открытии выставки «From a body I spent». Фото: Виктория Экста

При этом важно не забывать, что одну и ту же историю можно рассказать с совсем разных точек зрения.

Используя чьи-то свидетельства, я никогда не утверждаю, что вот это единственный, «истинный» нарратив. Люди субъективны, это вот земля и природа – объективны. Недавно я занимался одним проектом в Китае, там пустыня Гоби надвигается на окрестные деревни и поля. И когда мы изучили эту тему, выяснилось, что нарратив, которым привыкли описывать происходящее в этих местах, очень редуцирован, упрощён.

Сначала мы отправились в деревню, о которой сообщалось много раз в самых разных масс-медиа. Мы провели там несколько недель, общаясь с местными людьми, просто гуляя по окрестностям. Опросили где-то около сорока человек. И там были самые разные точки зрения. Но в конце концов выяснилось, что начальный посыл «пустыня пожирает деревни» был абсолютно неверен. Потому что пустыня здесь и была – на протяжении столетий, но людей с гор пересилили сюда и заставили «культивировать» эти места, возводить здесь деревни – таково было решение центрального правительства. А теперь пустыня возвращается. Просто потому что она была здесь всегда. И мы выяснили это всего из нескольких разговоров с местными и из одного короткого визита в тамошний архив.

Tides of Sand and Steel. Si Shang Art Museum. Пекин, Китай. 2017

A conversation in Riga with Felix Kalmenson, Canadian artist with ‘soviet’ roots

Sergej Timofejev

19/03/2018

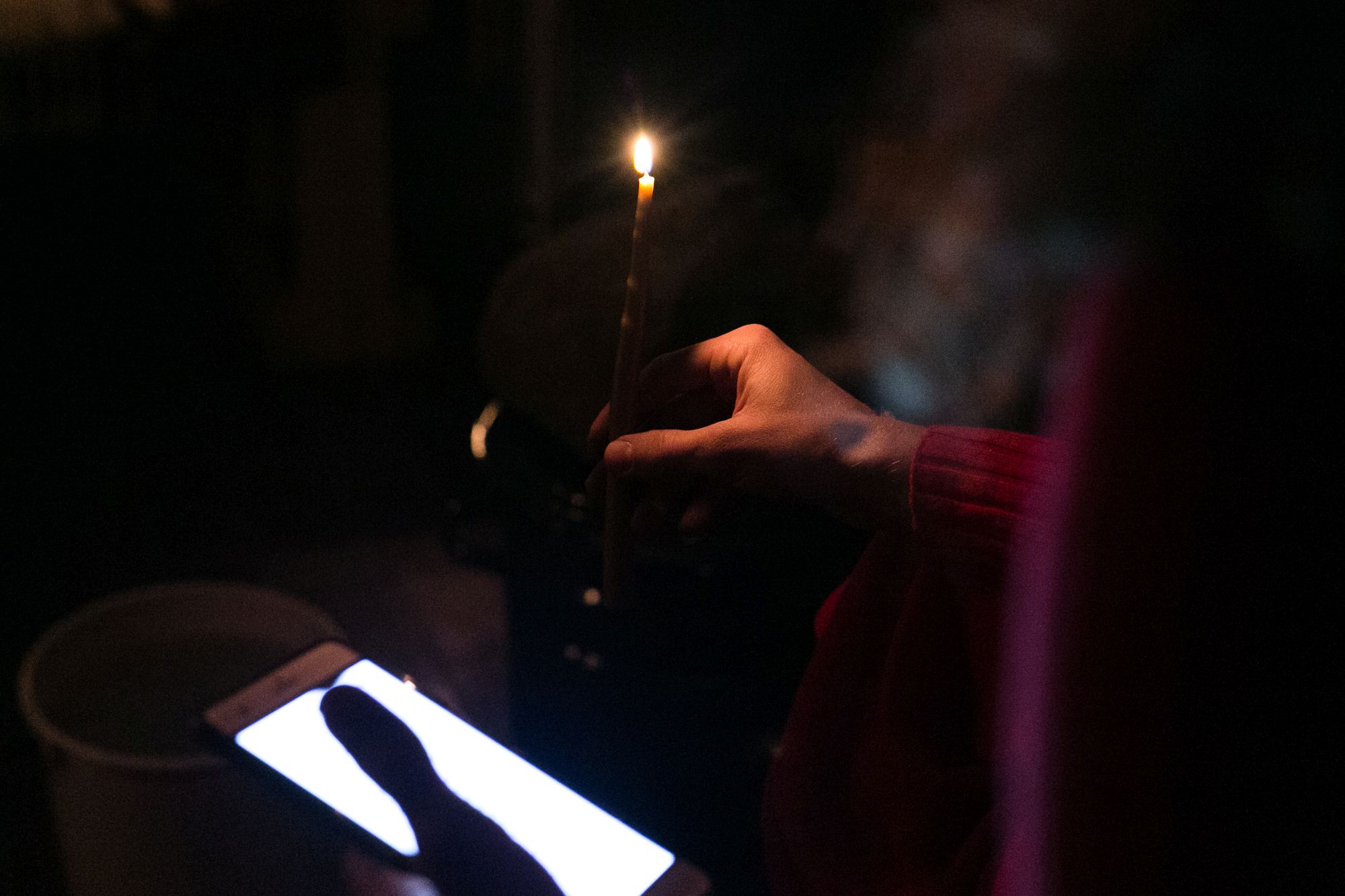

Through 1 April 2018, the kim? Contemporary Art Centre hosts From a Body I Spent, the Toronto-based artist Felix Kalmenson’s first solo exhibition in the Baltic states. It is a multi-layered show consisting of a number of video works, objects, installations and material evidence of the performance presented by Felix at kim? for the opening of the exhibition. At the time, he read an essay of his own writing while pacing a circular wooden construction, then moved on to producing wax candles in an allusion to an ancient Yiddish exorcism ritual of which he had only learned a few years ago.

Felix was born in then still-Soviet Russia, in Leningrad. His family later moved first to Israel and then to Canada. Moving, travelling, changing spaces is an important part of his life; he calls himself a “rootless cosmopolitan” appropriating the antisemitic Soviet term and says the key phrase of his life, borrowed from the American poet Theodore Roethke, is “I learn by going”. At the same time, in his very poetic works, grand and small narratives form a kind of a vibration of stories, their multidimensional embodiment, which by virtue of the multitude of layers almost equals life in its level of veracity. The search for one’s own space, one’s home, can take place in the endless expanses of Google Earth, or in a video shot by an unnamed late 1980s cameraman in exchange for a Leningrad car mechanic’s salary. Memory, history, never-to-be-forgotten injustice are the subjects he holds important.

From the exhibition From a Body I Spent. Photo: Viktorija Eksta

Felix and I meet up at kim?, sit down on that very same wooden construction together with the Greek-born exhibition curator Maya Tounta, and, armed with large cups of peppermint tea, prepare to converse. I hand Felix a gift – the recently published “Rīgas Līcis”, a book of Vladimir Svetlov’s photographs of a now long-mothballed Jūrmala sanatorium of the same name, which closed in 2003. Felix leafs it; the visual content appeals to him and elicits his own story in reply:

My grandmother grew up in a similar sanatorium on the coast of the Gulf of Finland, where her father was the director. It was a Creative House used by various artists and musicians. She was very pretty and inspired the local “creators”, who painted her and composed music for her. She was like a muse of the house, collecting men’s hearts as she went about her business.

Are your parents from St Petersburg?

My father is; my mom was born in Estonia and lived in Tallinn until her decision to leave and study medicine. Her parents came from Belarus, but my paternal grandmother is half Armenian and half Russian, and my paternal grandfather is from Ukraine. So in the essay I read at the beginning of the performance I call myself a “soviet”, because I consider myself a product of the mixing of people and their geographies that is characteristic of the era.

And did you move to Canada from St Petersburg?

No, from Israel.

That’s to say, your family moved there first?

When the borders opened in 1989, many Jews were leaving. We, too, decided to go to Israel at first. It was common practice at the time – since there were no direct flights to Israel, people flew via Rome or Vienna. However, once in Rome, they said that they had no intention of going on to Israel…

Prelude, 2016. Video Shot.

That their plans had changed…

Yes, and that they wanted to seek refugee status in the USA, in which case they were allowed to stay in Rome until their fates were settled. This was even called “the Roman holiday” at the time – after the film of the same name. They stayed there a month or so, while the necessary papers were prepared, and then went on to America. But we were among the idiots who didn’t change their plans and flew out to Israel. The people around us were shocked: ‘Why would you go there? Go to the USA!’ But my parents had some relatives who had emigrated to Israel in the 1970s. They wrote us letters saying that everything was great over there, that it was easy to find work, that there were so many options. And then it turned out that they were simply feeling bored there; they wanted some company and so in a way they duped us. As soon as we found ourselves in Israel, all hell broke loose – the Gulf War, the Intifada. What’s more, the Israeli authorities treated the USSR emigrants as second-class people. Simply as a workforce and bodies to be employed in the border area. We were settled not in a classy Tel Aviv flat, but right on the border…

And your family decided to move to Canada.

Yes, in December 1993.

How old were you?

Six and a half.

Trailer for video work House of Skin (2016)

Do you have any memories from that time?

Yes, and quite a few. To be honest, my memories of Israel are rather mythological. Something along the lines of the first downhill ride on a bicycle. And the fall I took along the way. But, of course, there are also missile attacks, gas… In my video House of Skin, I use street view on Google Earth to visit all the places we lived. And I try to see them. Because at the time I could neither go back to Russia, nor to Israel (where I would be jailed for avoiding compulsory military service). So I decided to visit these places virtually. I tried to find these locations by memory, by the fragments of the surrounding reality that I remembered. This is how I found the house where I thought our flat in Israel had been. I showed it to my mother, and she was astonished: “How did you manage to remember that?” I was so little when we left. And then she helped me find the house where we lived in Leningrad. But later it turned out it wasn’t the right flat – or the right house. Mom’s not so good with geography and coordinates. Some time later, when I was working on Neither Country, Nor Graveyard and was about to go to St Petersburg, I spoke to my father, and he really did give me precise directions for where we had lived, where he had worked, where Mom had worked. After all, this was his city – the city where he was born and grew up. So that’s when it turned out that the house was in a completely different location, a five-storey building on the outskirts of the city. As for House of Skin, I left everything as it was, because I thought this disconnect between reality and our memories was a very interesting thing.

In Neither Country, Nor Graveyard, there is some video material of St Petersburg (then still Leningrad) from 1989, which you combine on a single video plane with the material shot by yourself at the same locations. But who shot the video back in the late 1980s? It looks very professional – panoramic shots, steady camerawork.

It was a specially hired cameraman. At the time, camcorders were a rare thing in the Soviet reality. My father told me he had only known one such person and had given him his entire month’s salary to make that video. But he also did it because at the time when we were about to emigrate, the existing law stated you could not take all your money with you. Dad told me the permitted sum was something like $ 100 per person. So he invested his money in memories.

Neither Country, Nor Graveyard. 2017

He asked the cameraman to film not just his family but also the city itself.

Exactly. It’s a little strange from the point of view of making a ‘document’ – there is no record of our flat, or our part of the city. It’s mostly very touristy locations. Anyone who has spent at least a day in St Petersburg will know these spots. And my parents were almost playing tourists in their own city, wandering about among parks and monuments.

By the time I returned there 27 years later, I had forgotten all of these places. So I found myself a tourist in the city where I was born. And this interplay between the two “touristy” walks, separated by time, seemed interesting to me. There is a very intimate connection between human and landscape. I remember being in Riga – before I had been back to Russia – and crossing the Stone [Akmens] Bridge on the Daugava, the one that now leads from Old Town to the National Library. It reminded me of one of the bridges in St Petersburg, and walking across it gave me a very strange feeling in my chest, something like an attack of unbelievable melancholy and sense of déjà vu.

I think that memories of events and places also leave their mark on us on a genetic level. When I arrived in Vilnius for the Rupert art residency, I took a taxi from the airport, and on our way, we had to pass through a forest, a pine forest. And I had another strange sensation – like I had cried in this forest so many times a long time ago, or something to that effect. I did not understand it at all. But these things can be explained by genetic memory. By the way, my mother is a geneticist, she still works in the field.

As we live our lives, we have our genetic code, a set of genes which is either degraded or, on the contrary, added to by our experiences. The more trauma and conflict a person has in their life, the more epigenetic tags are left on this set. It used to be thought that these are all “nullified” at the birth of a child, but it turns out the most painful and traumatic marks are passed on to the following generations.

There’s been research on the effects of the Holocaust, linking them to suicide, depression and heart disease. Because whenever you experience stress or depression, your heart is the first to be affected. But this is in no way a uniquely Jewish issue. There is research on the subject in connection with the experience of race, the ghettoization of the black population of America. It changes the way we view the idea of an egalitarian society, a society of opportunities. It turns out we need to take into consideration the past of our ancestors; it cannot be discounted or erased. It directly influences our physical and mental health.

Growths. 2012. This video work is the result of several months of cultivating mould on 35mm film containing Hollywood trailers from the last decade.

It seems the sensations you experienced in the forest have spilled over into your work from last year, The Taste of Real Bread, which is based on a fragment of the memories of Fania Brantsovsky, a Holocaust survivor who joined the partisans in a very similar Lithuanian forest just 40 km from Vilnius.

Yes, I was in Lithuania doing my research on the Bund, the Holocaust and mass murder sites in forests. The very same forests that later sheltered Jewish partisans who had escaped slaughter. The forest was like a living witness of all these stories. And the way a forest interacts with light… sometimes I feel it is “playing”, “performing” something for us. So much can be said without words here. An enormous cloud will cover the sky, enveloping everything in darkness; then it will move on and give way to a moment of enlightenment, almost, of clarity. In a sense, the forest plays the role of a storyteller.

In this video the forest truly is amazing. It looks not at all gloomy, and completely alive…

Yes, absolutely.

Spectators by the work The Taste of Real Bread at kim? in February 2018. Photo: Viktorija Eksta

When you express, condense your own memories in your works, how do they change within yourself? Do they stop bothering you, or…?

It’s like therapy in a sense. It’s like a conversation with a psychoanalyst who helps bring your most important memories to surface. For example, I made House of Skin at a time when I was confronting my own internal issues. There’s the trauma of the missile attacks in Israel, the trauma of sexual abuse that I suffered in my own family, the trauma of double emigration. It all weighed very heavily on me. And I realized the best way of dealing with it was to work through it; to work my way through and out.

I have a favourite phrase: “I learn by going”; I often repeat it to myself, especially when I feel lonely or lost during my travels. And I decided to “go” through it all using the machine vision of Google, or the visual experience of other people’s YouTube videos, or my own family photographs. To immerse myself into all these voices and come to some sort of awareness. Editing the video was a rather difficult task, it took me several months. I am not normally an overly emotional person; usually I only cry at the movies, at some fleeting expression of beautiful humanity. Yet here I was, in tears every week. I wept from the sadness of it. But this was the therapy I had avoided throughout my life until this moment. Afterwards, it was hard for me to show the film to others, or even to decide that it was complete, finished. I kept “editing” and changing it for almost two years. But in the end it all led to some semblance of acceptance within myself; it did not solve the problems for good, but they could no longer drive me to tears.

You tidied it all away to its proper place, into a kind of a cubbyhole in your mind.

Exactly. And the same was true of the forest film. I was just as moved by the material – this unbelievable level of violence – and the way in which it all later became subject to political bargaining. And not just in the hands of the Lithuanian government, but also of the local Jewish community of Vilnius. Because in truth there are two separate Jewish communities: one that is involved with the current state of affairs, with real estate or business deals; and the community of survivors, who have a completely different understanding of the core of the issue: all they want is justice.

Interestingly, conflict – internal and external – plays quite an important role in your art. Even though you don’t exactly project the image of a conflicted or confrontational person.

No, I am a very peaceful man. At least as long as I’m getting enough sleep and coffee for breakfast.

Fountain. 2015. Landscape installation of solar-powered garden fountain on top of a sand dune in the Sahara Desert.

But, for example, right now those entering the kim? exhibition are greeted by your work Highway 80, dedicated to an episode of the Persian Gulf War in 1991 – the attack of allied American and Canadian forces on Iraqi soldiers withdrawing from Kuwait and the Palestinians who were moving with them.

This work is an attempt to hinder the hushing up of this incident, which many consider to be a war crime. And a moment that escalated the level of violence and casualties in the Middle East. As a person in whose name the victorious Western forces were acting at the time, I feel a moral responsibility not to allow this outbreak of violence to be forgotten.

Yes, it happened more than two decades ago. But we cannot understand the current crisis of refugees from Syria and Iraq without understanding the Gulf War, and without considering the post-colonial history of that region. Not so long ago, ISIS consistently referred to the injustice of the treaties signed by the Western powers after the end of WWI and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, viewing it as justification for the establishment of the 'Islamic State' in those territories. Yes, for them it was just a theoretical foundation for a new round of violence. But we cannot unravel the entire knot of contradictions in this region without assimilating what happened a hundred years ago.

I view these things as the ethical duty of every person. It is not an easy task, but without the recognition of the past there can be no movement towards something positive in the future. Remember the optimism of the 1990s, that “end of history” and the universal joy it elicited? Why had the subject of the Holocaust turned out to be so problematic for Lithuania at that very same time? Because there was this feeling of the end of a difficult era, the Soviet era, of moving into a free and easy liberal capitalism where anyone could be whatever they wanted to be. Everyone was supposedly equal, everyone had the same access to the international market. At that moment they did not want to delve deeper into history. But you cannot avoid it; you can only pretend that it has come to an end, that it is no more – but history will never just go away.

It will, for instance, live in the memory of the older generation, and this is one of the reasons why the older generation so adamantly tries to distance themselves from the younger people, from the direction in which countries are moving today. And the older generation reacts to it in their own characteristic manner – by rallying under Soviet flags or nationalist slogans. They are afraid of a total erasure of their experience, of everything they’ve lived through passing into oblivion. And you can see this in many different countries.

People who have lived all this history in their lifetimes know how truncated, how reorganised it has become. The Iraqi National Guard soldier whose story is used in Highway 80 knows the other side of history. Fania Brantsovsky, who has lived under four different regimes (Polish, German, Soviet and Lithuanian), knows it all too well. She can attest that a state is not a stable concept. It is a fragile entity that can collapse just as easily as any corporation or society, any family or individual.

By gathering these testimonies, these destinies, in a way we become “archivers” of history: we don’t want our history to be taken from us, reduced to a level that somebody finds more convenient. By preserving this knowledge we become an obstacle to the emergence of new fascist, nationalist state formations. And this knowledge can be lost, should history be approached simplistically.

Stills from Felix Kalmenson’s performance at the opening of the exhibition From a Body I Spent. Photo: Viktorija Eksta

In addition, it is important to remember that any one story can be told from very different points of view.

Whenever I use someone’s testimony, I never claim it to be the only or the “true” narrative, people are subjective. Not long ago, I was working on a project in Western China, where the Gobi Desert is moving in and swallowing the surrounding villages and fields. When we studied the subject it turned out that the narrative commonly used to describe the situation was a very reduced and simplified one.

First we visited a village that had been mentioned a multitude of times in all kinds of mass media. We spent a week getting to know the locals and just wandering around the area. We chatted with some 20 people. And there was a variety of views. But in the end it turned out the initial message of “the desert devouring the villages” was so wrong. Because the desert had always been there, over centuries and centuries. People were moved there from the mountains and instructed to “cultivate” the land, to raise villages – as decreed by the central government. But now the desert is returning. Simply because it has always been there. And we learned it from only a few conversations with the locals and a single short visit to the local museum.

Tides of Sand and Steel. Si Shang Art Museum. Beijing, China. 2017