A conversation about Boris Lurie

The German curator and art historian Eckhart Gillen tells about the phenomenon of Boris Lurie and NO!art. An extensive retrospective of this art movement is on view from 11 January through 10 March 2019 at the Riga Bourse Museum.

01/02/2019

The short story goes like this. Boris Lurie was born in St Petersburg (then Leningrad) but the family soon managed to emigrate to Latvia, Riga, where they lived until the Second World War. When Boris was 17, he and his family were imprisoned in the Riga Ghetto from where the men (Boris and his father) were eventually moved to a labour camp, while his mother, sister and his first love were killed. It was only in 1945 that Boris was liberated by the American troops; these four years at the concentration camp, the time that in another life, a normal human existence, would be spent studying, exploring the world, building his self, became an inhuman school of death and survival, the lessons of which he could never forget. Accompanied by his dad, who had also escaped death (their inmate numbers were successive, 95966 and 95967), Boris moved to America, where the father became a successful developer and the son started a search for his path as an artist.

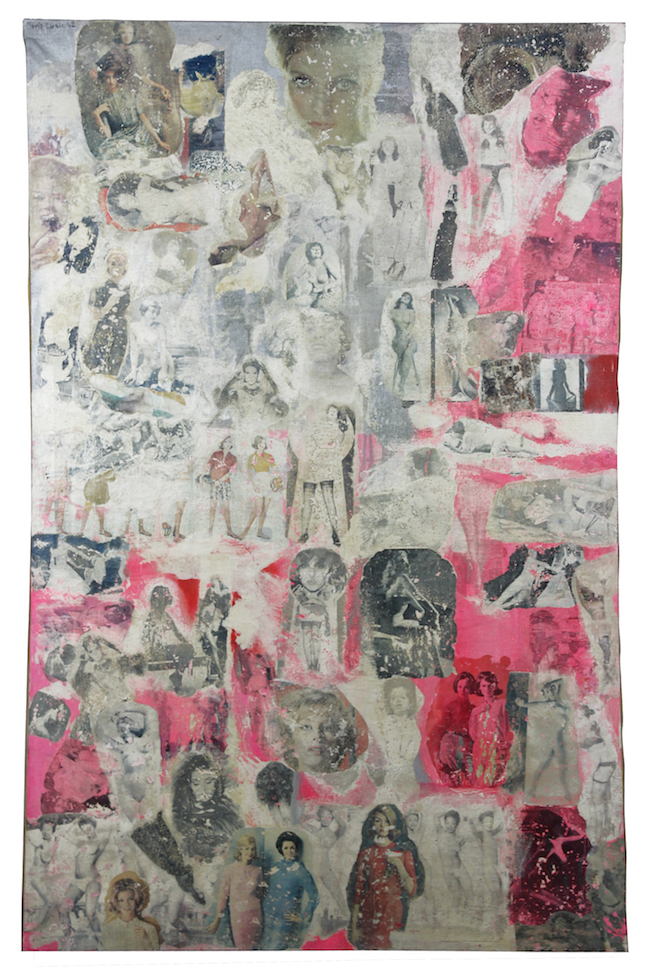

Boris Lurie. Love Series: Bound on Red. Ca. 1963. Photo emulsion, acrylic on canvas. Collection of the Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York. Publicity photo: ©Boris Lurie Art Foundation

Lurie’s first works were closer to expressionism but gradually he started to find his own way ‒ one that turned out to be inconvenient, hard to stomach and out of place in the New York of his time. There was too much pain and screaming in his art, too much darkness and trauma. His collages feature piles of female bodies, images from men’s magazines; these bodies are glued together, stacked up like corpses in the wagons of Buchenwald. As Lurie saw it, woman in a consumerist society is a similar object of symbolic (and non-symbolic) violence and appropriation to the Untermenschen under the Nazi regime. For this reason, these ‘nude pics’ are literally mixed with photographs of the stacks of killed camp inmates, like in his iconic 1963 piece ‘Railroad Collage’. It is perhaps also a scream of pain about the impossibility of love, collapse of trust and intimacy after this experience of ‘living death’. Those were not works that would cater to the artistic preferences of the critics, collectors and art dealers of the time.

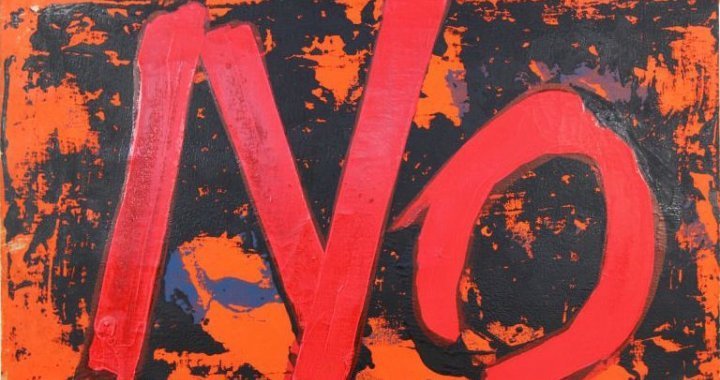

Awareness of the path of his contemporaries towards their artistic success made Boris Lurie radically reject the whole art system of the time. According to the American art critic Donald Kuspit, ‘his negativity deeply informs [his art], giving it the strength to survive in the concentration camp that the artworld came (unconsciously) to seem to him, even as it ironically indicates that he belongs to it, for his art was as cutting-edge avant-garde, and with that as negative in its import, as the celebrity avant-garde art—Abstract Expressionism—that was all the rage at the time.’ In the late 1950s, Lurie with several like-minded friends and artists invented the NO!art movement, whose manifest said, among other things: ‘ [We are] against the pyramiding of artworldmarket-investment-fashion-decorations ("minimal", "color field", "conceptual"): such games-decorations are the sleeping pills of culture.’

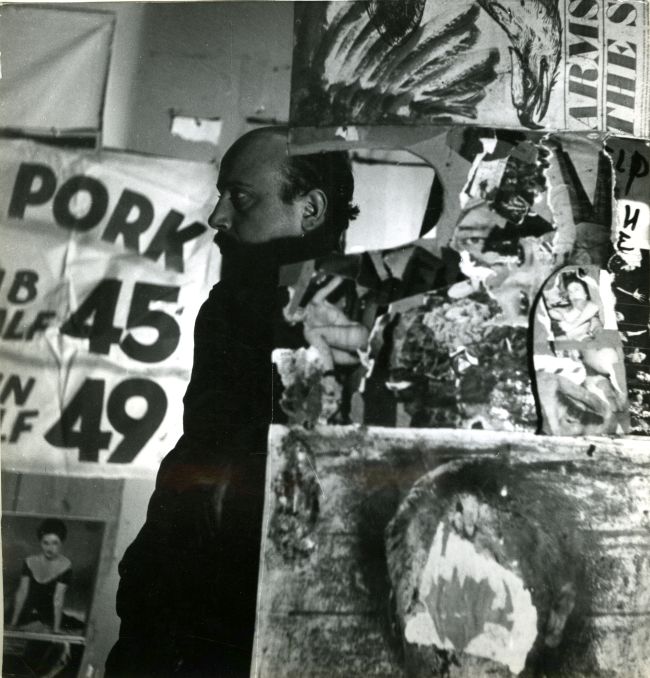

Boris Lurie in his Studio. Ca. 1961. Collection of the Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York. Photo: Sam Goodman. ©Boris Lurie Art Foundation

Boris Lurie in his Studio. Ca. 1961. Collection of the Boris Lurie Art Foundation, New York. Photo: Sam Goodman. ©Boris Lurie Art Foundation

Boris later wrote about it: ‘It started out of desperation because we were already some time in the art world, and finally we saw what was going on and said “To hell with you, we want to be artists but we’ll do it for ourselves, we won’t be involved with you.” And if they want to, they can try to get us.’ The group was active through the mid-1960s, and a number of galleries worked with it; meanwhile, Boris Lurie was never involved in selling his own works. He was initially supported by his father and later managed to earn his own living; by the end of his life, Lurie had accumulated enough wealth to launch the Boris Lurie Art Foundation. It is this foundation that manages his artistic legacy today, and it was this foundation that helped mount the ‘Boris Lurie and NO!art’ exhibition in Riga, curated by the art historian and gallerist Ivonna Veiherte. The opening of the show was marked by the publication of a remarkably detailed catalogue jam-packed with documents (a seriously weighty and impressive volume); a conference dedicated to the exhibition was held at the Riga Bourse Museum, attended by the German art historian and curator Eckhart Gillen. We spoke on the eve of the opening, right there at the museum ‒ some 10 or 15 metres from the works by Boris Lurie and his fellow artists.

Eckhart Gillen. Photo: Ilmārs Znotiņš

Eckhart Gillen. Photo: Ilmārs Znotiņš

Why are you interested in Boris Lurie and how did you first encounter his works?

My generation was formed by the movement of 1968. I moved to West Berlin in the early 1970s, and I was always interested in art from the vantage point of its relationship with society. I grew up in a very conservative family, attended a school of the same type and lived in a city of the same type, and I was craving something different. From the other side of the Iron Curtain they were promoting some sort of utopia, and we had no idea what was going on there in reality; the newspapers were filled with the typical Cold War rhetoric. And that is why I decided to move to West Berlin, a city on the border of this ‘socialist project’. The Wall was just ten years old at the time. The art circles of West Berlin had already split into the conservatives and the leftists, and it was the left who arranged the first Boris Lurie exhibition in the city. They were interested in artists who were questioning the typical art scene, art market and the system where directors of art institutions and art collectors decide who is worth what.

That is how I first met the works of Boris Lurie ‒ at the exhibition at Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst, the art space where I was curating my first exhibitions dedicated to the Cologne constructivists or the 1920s Soviet avant-garde and the way it transformed with the changes in the society.

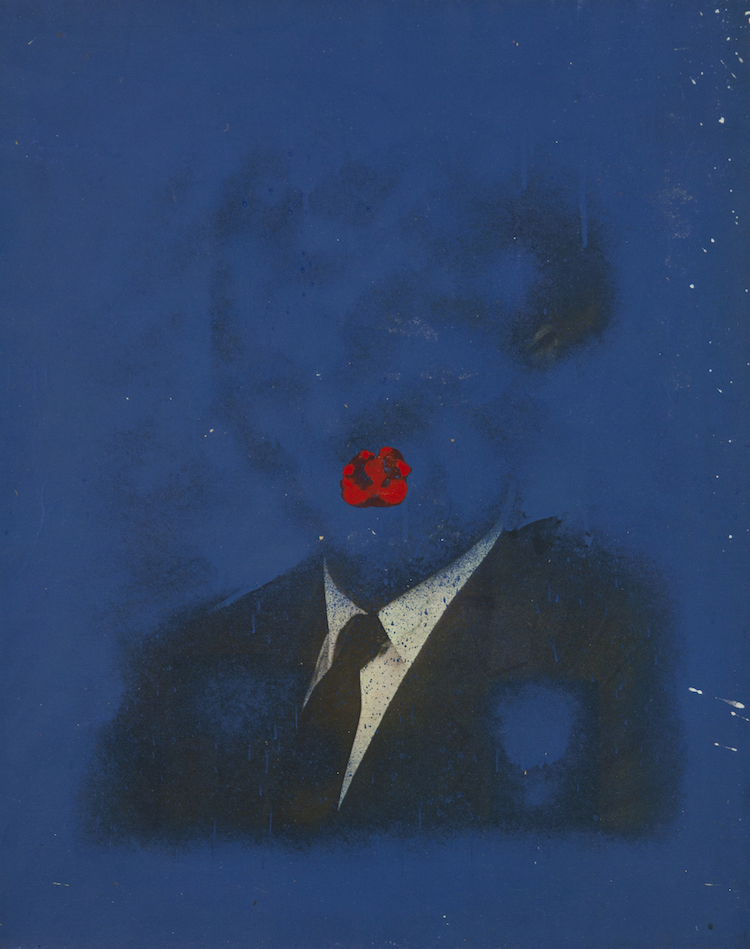

Boris Lurie. Altered Man (Cabot Lodge). 1963. Painted paper, canvas © Boris Lurie Art Foundation

Boris Lurie. Altered Man (Cabot Lodge). 1963. Painted paper, canvas © Boris Lurie Art Foundation

What is your angle on Boris Lurie? What are you going to speak about at the conference tomorrow?

I am going to speak about the ways in which he challenged the American art scene and art circles of the time, comparing them with a concentration camp. At the end of my talk I am going to quote from his novel ‘House of Anita’; the building is simultaneously a brothel and a top-class art gallery. In the novel Lurie demonstrates that we are all slaves in a capitalist society, that it is the same old system of subjugation. Concentration camps are also, in a way, successors of the Enlightenment, successors of the idea of ‘progress’. But the artists in the novel are not prisoners, they end up in the brothel voluntarily ‒ which does not change the fact of enslavement and domination.

It is sometimes hard to grasp. We do live in a free society, in a free market society where we make our own decisions about the things we do or do not buy. We think that we are free, but it is an appearance only. It is simply that this subjugation is not on the surface, its roots are much deeper than that. Boris Lurie tried to make it obvious. Approximately the same thing was done by the young artists of Eastern Germany who thought that you should not make everything more beautiful, should not embellish the picture if you live in a totalitarian country. And they expressed it in a somewhat morbid and obvious performative manner.

Boris Lurie provokes the viewer and says that the situation in the art circles is even worse than in a concentration camp; at the same time, his works are also a way of remembering for him, a way of making his memory work. When he was liberated from the camp with his father, Lurie did not think of himself as a victim. New horizons were opening up for him, and he decided to go to America and discover this country for himself. But then it gradually dawned on him that this experience was not going anywhere; it was going to come back and haunt him. And he needed his art to make certain things in the world around him more obvious while also remembering and processing the key moments of his experience.

In Lurie’s life there is this interesting thing that the memory work was initially taking place on a visual level; later he ‘evolved’ to the point where he felt that he could put it into words. He started with ‘Liberty or Lice’ in 1959 and fifteen years later came back to Riga for the first time after the war. He came to remember the days when the most tragic events of his life took place. And then he started writing. He wrote a novel, some poems but also a huge volume of memories. It was a very important time in his life.

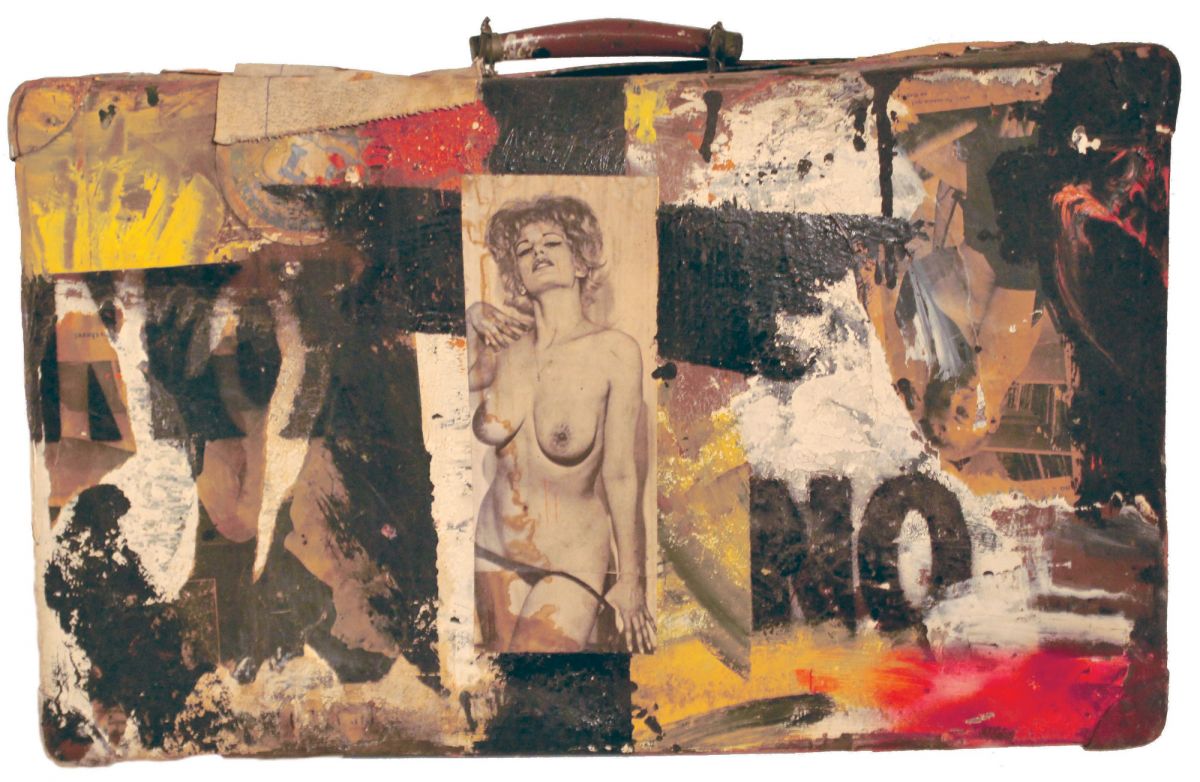

Boris Lurie. Suitcase. Circa 1964. Assemblage: oil paint and paper collage on leather suitecase. ©Boris Lurie Art Foundation

Lurie had very critical views on the situation in the American art world. But how did he survive in it himself ‒ how did he exist?

It was not easy. He seemed to be in the middle of the art world but when, for example, a very representative exhibition of assemblages (a technique frequently used by Lurie) was being mounted at MoMA, they initially chose some of his things for the show but then did not put them on view after all. If you read the press release for this exhibition, it says that assemblage is a form of high art. There was no politics there but lots of cubism and Dada (which at the time was already a phenomenon that belonged in a museum).

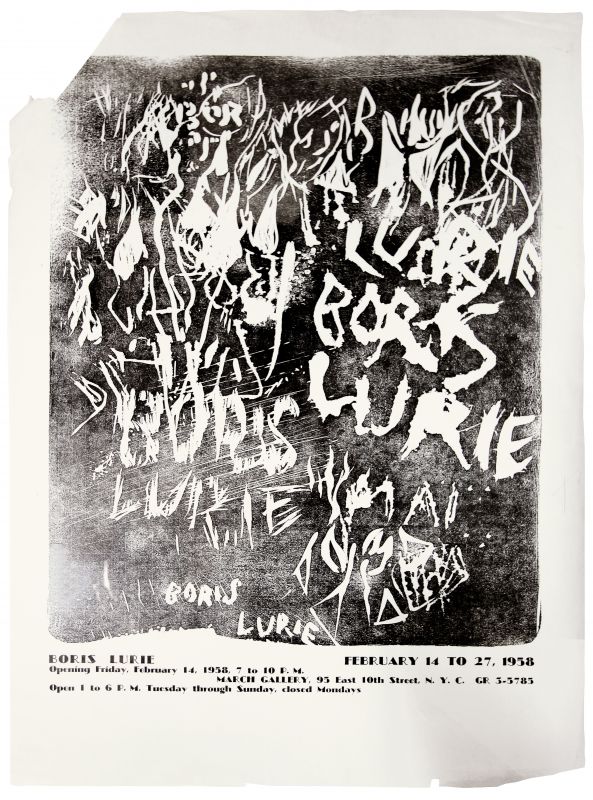

On the other hand, I think that he actually did not want a commercial success in art, he did not want to sell his works. The NO!art movement had its own gallery (the March Gallery), and from 1963 the gallery of Gertrude Stein (a namesake of the famous Gertrude Stein) also worked with them. Nevertheless, the dominating principle was creating art not for success and sales but because it was interesting and important for the artist to do that.

That is why he was initially supported by his father, a successful businessman who made his fortune on real estate. In 1964, when his father died, Lurie took over his business. Boris was against capitalism and art market but at the same time he was also a successful businessman ‒ as if he wanted to prove that he could do it as well as his father had done. He also traded in shares, played the stock market ‒ and that is an area that demands some serious knowledge and intuition. He managed it brilliantly and actually became a very wealthy person. And his foundation, set up with the money earned in this way, now helps mount exhibitions of Lurie’s art in various parts of the world.

March Gallery Poster. 1958 © Boris Lurie Art Foundation

And it is the foundation that owns his works now?

Yes, contact with the public was important for him. He showed his works, sometimes he gave them away, but, as far as I know, he did not sell a single one of them.

What is your take on the sexuality in his works? After all, he often used pictures from men’s magazines of the time, reworking them in his pieces ‒ juxtaposing, for instance, with horrific and creepy photos from concentration camps.

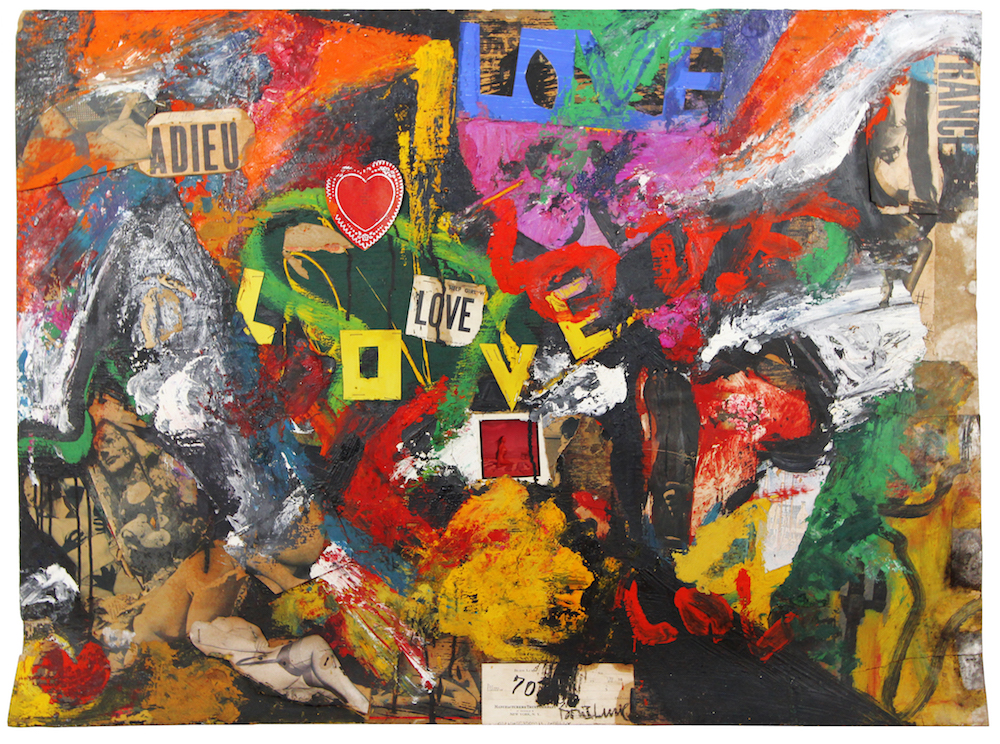

Clearly, they do not affect you as pornography. Because on the foreground there is always going on a certain confrontation with death; these are deconstructed images. And what was destroyed in his life by the intrusion of the concentration camps (where he lost not only most of his family but also his first girlfriend) – that was real love, something that he was unable to find in the American society of the time where everything was subordinated to the dictate of profit and you yourself act as a marketing project of fluctuating value. He said that he cut these images out of magazines and stuck them on the wall. And they seemed to haunt him. He felt that he had to do something with them. So he took them off the wall, put them in his pictures and started covering them with colour, with paint.

Boris Lurie. Feathers. 1962. Paint, collage on canvas © Boris Lurie Art Foundation

So initially for him they were images he found interesting on a sexual level?

Of course, and it was about his longing for intimacy, for a contact with a woman, for love. But what happens is taking this sexual intention to the point of its destruction. We can desire a beautiful body but when there is a hundred of bodies in a picture and they are covered in paint, it is chaos ‒ it is more like a battle field than an object of desire.

Boris himself did not actually have a proper family. He had a relationship with a French lady and, I think, they even were married for several years. But they never shared a house or a flat. For him that was impossible.

And this impossibility of love ‒ after the experience that he had lived through and in the society where he had found himself ‒ pushed him to create works of this type. It is very interesting that, given his critical view of capitalism, he was personally dealing very well with the system, ‘operating’ with it successfully. He lived a very modest life, however, as if existing in a sort of ghetto. But he could have afforded a completely different way of life. All of his assets he invested in his foundation, the Boris Lurie Art Foundation.

Boris Lurie. Untitled (Adieu Love). C. 1960. Oil, acrylic, paper, photos, staples on cardboard © Boris Lurie Art Foundation

Boris Lurie. Untitled (Adieu Love). C. 1960. Oil, acrylic, paper, photos, staples on cardboard © Boris Lurie Art Foundation

Perhaps he was mostly ‘investing’ in his independence, which was for him the greatest value.

Yes, exactly, in an ability to remain independent. In art and in life alike.

He was part of the NO!art movement. I wonder to what extent it was actually made formal as a movement...

I think it was, for a number of years. It is a typical art world story ‒ you found a group to help each other, you solve certain problems, and then some five years later the collective starts to fall apart. Boris Lurie was the leader of the group, but Sam Goodman also played an important role ‒ not only as a sculptor but also because it was he who gave Lurie the photographs taken in concentration camps. But he also made quite interesting objects himself. Stanley Fisher worked in a manner very similar to Lurie’s except he maybe lacked some of the originality. By the way, the membership list was never strictly defined. For instance, Yayoi Kusama was also very close to the group and she also showed in their exhibitions. And she was not the only one.

I think that the movement was more important as a confirmation that many other artists also had similar views and were attempting to solve the same problems: how do you become independent? How do you leave the system of subjugation to galleries and art dealers?

Exhibition view at the Riga Bourse Museum. Photo: Andrejs Strokins

Exhibition view at the Riga Bourse Museum. Photo: Andrejs Strokins

Do you think the fundaments of the art system have changed significantly since the time of Boris Lurie?

I think they have, yes. I think that the ideas of introducing art into life or the autonomy of art have finally reached the point where the actual art seems to dissolve. That is a huge problem that can be noticed both at the Venice Biennale and at documenta. The latest edition in Kassel featured a very impressive project where the artists carried out their own investigation of a relatively recent murder that was connected with the National Socialist Underground. Art seems to dissolve, replacing social reportage or police investigation. It is becoming more like scientific work or political activity but it engages emotions less and less. A work of art, of course, has the right to be independent and it absolutely can relate to the society and its problems ‒ but unless there is actual art in it, something has been lost. We are sort of following the same trend that is stemming from the selfsame Lurie, NO!art and the 1960s, but if we go overboard with that, the actual art disappears. Having said that, Lurie’s pieces ‒ not all of them but many ‒ are essentially very powerful and real works of art.

Exhibition view at the Riga Bourse Museum. Photo: Andrejs Strokins

What are the latest developments on the German art scene ‒ perhaps something interesting that we are not informed about?

I would name the Centre for Political Beauty movement (Zentrum für Politische Schönheit @politicalbeauty) working in art intervention. For instance, we have a right-wing politician in South Germany who says that a memorial dedicated to the Holocaust should be dismantled ‒ that Germans should not have any monuments to things that we should be ashamed of. That we must find positive examples in our history and build monuments marking these events. So this group of artists built a copy of the memorial to the Holocaust victims right in front of his house. He was terribly angry, but there was nothing he could do. He was now surrounded by the very things he had been fighting so much. The members of the group come up with all sorts of interventions that help us process the changes currently going on in Germany. My generation could not imagine that we would ever return to populism, to increasingly right-wing ideas and the threat of totalitarian structures. We thought all of that had gone away ‒ if not forever then at least for a very long time. And yet the problems have re-emerged, and not only in Germany. There are Trump and Putin, there are the things that take place in Poland, Romania and elsewhere. They tell us ‒ we are democrats like you, we are just like you were in 1968, we are also fighting with the old elite, it’s just that it is you who are the old elite today. We will also hold demonstrations, we will also fight to change the situation ‒ and bring it back to the pre-1968 world. Symptomatically, one of the most prominent politicians of this wing is a woman, and a lesbian. And it is as if she did not understand that this situation where a woman can be a prominent politician and not hide her sexual orientation was only possible today because there was the year 1968.

Exhibition view at the Riga Bourse Museum. Photo: Andrejs Strokins

A year ago, at the exhibition ‘YOU’VE GOT 1243 UNREAD MESSAGES. The Last Generation Before the Internet. Their Lives’ at the National Museum of Art, which ‒ for the first time in Latvia ‒ featured two works by Boris Lurie, I also remember seeing a documentary series of photographs; the context had to do with the marriage law that still existed in Germany in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The law stipulated that a man who was married to a woman had the right to decide whether she was allowed to work or not. Basically, he had the right to turn her into a housewife.

My mum had a very successful career at a bank but my dad ended it two days after their wedding ‒ although he was himself unemployed at the time. This is, of course, incredible. And yet it was the reality of the pre-1968 world.

Eckhart Gillen at the Riga Bourse Museum. Photo: Ilmārs Znotiņš

Eckhart Gillen at the Riga Bourse Museum. Photo: Ilmārs Znotiņš