Art Brussels. Art fair in the city of two hundred galleries

The trends and challenges of Art Brussels in a conversation with the director of the art fair Anne Vierstraete

03/05/2019

The latest, 37th, edition of one of the highlights of the European art events calendar, the Art Brussels contemporary art fair took place over the second half of last week, between 25 and 28 April 2019. Launched back in the glorious 1968 and now housed in the halls of the enormous Tour & Taxis complex (the former train station and a whole cluster of related buildings), the fair focuses on the art of today: practically there were just a few galleries offering late modernist art or presenting long-time established “museumesque” names. And yet the sheer range of the represented art is impressive: 148 galleries from 32 countries, showing some 800 artists.

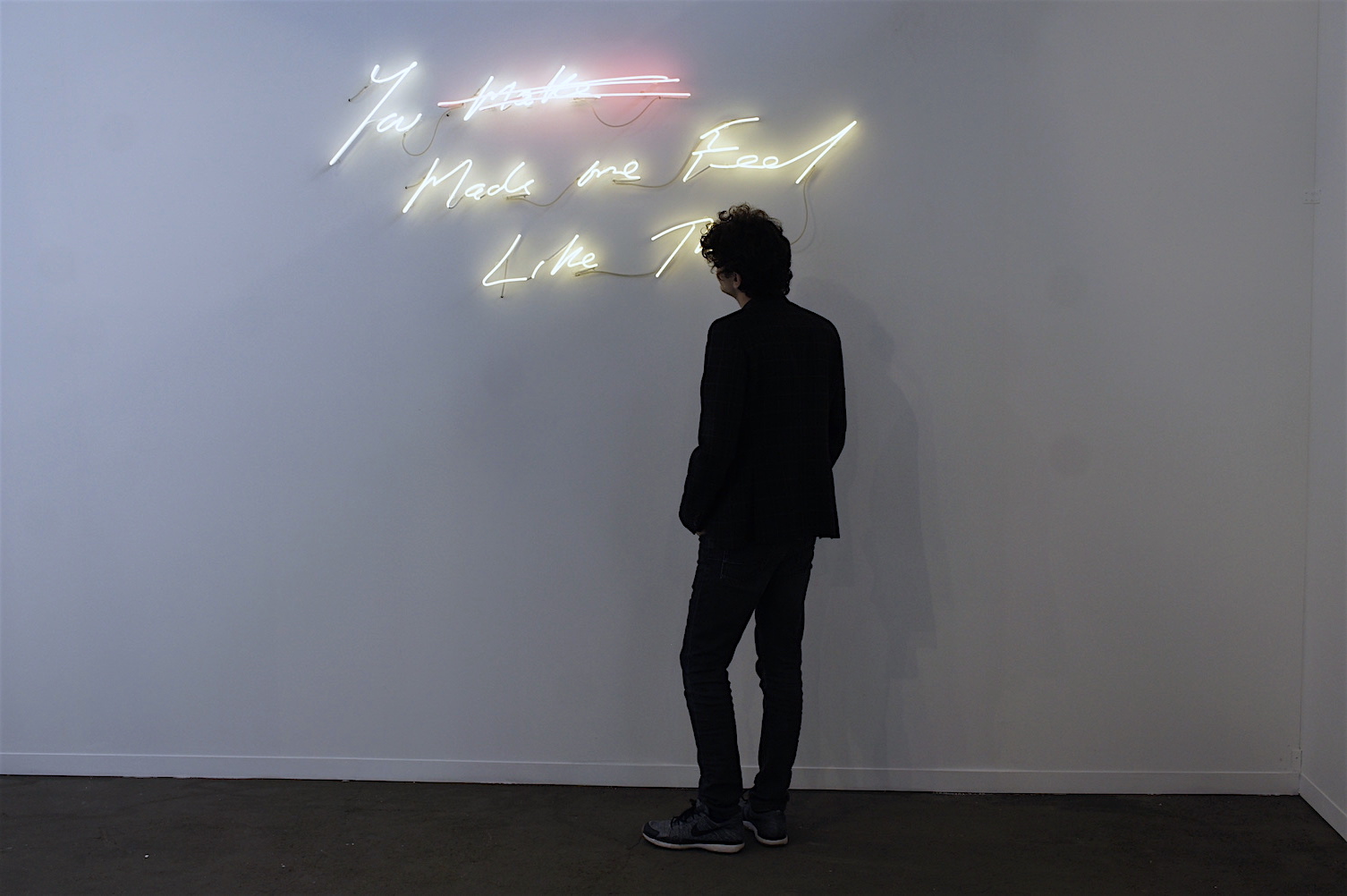

Tracey Emin. You made me feel like this (2018) / Xavier Hufkens gallery. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

The very existence of Art Brussels is deeply rooted in the essence of Brussels, a cosmopolitan city, the capital of EU and formerly not just of a country in the centre of Europe but of a whole colonial empire. Anyone rambling through the streets of Brussels inevitably stumbles across countless galleries presenting the traditional art of Middle East and Africa. In fact, there is an abundance of galleries and art centres of any description, some 200 of them dedicated to contemporary art alone. And many of them seem to be doing quite well: during the traditional Gallery Night preceding the actual fair, we had a chat with Laurence Dauwens, the co-owner of the Dauwens & Beernaert gallery located in the city centre. Active for a mere three years, this art space has already been able to become the owner of its own premises (an impossible dream for most galleries based in the post-Soviet countries ‒ but not just there). Laurence himself comes from a family of art gallerists, and this also plays an important role here: after all, the local clients are also frequently second or third generation art collectors. The circle of Belgian collectors is quite wide and representative (incidentally, one of the most famous names here is Galila Barzilaï-Hollander, who recently served as a member of the Purvītis Prize jury and presented a part of her collection at the Latvian National Museum of Art). And yet the art fair definitely also attracts a wide range of collectors from outside Belgium and the EU. Some of them select their purchases even before the opening of the art fair exhibition ‒ either based on the received preview materials or through constantly keeping in touch with the galleries, and that explains the appearance of the much-desired white-on-red signs with a single word ‒ sold ‒ in front of some of the booths as early as the day before the official opening.

Fragment of the stand of the gallery O V Project. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

The exhibitions presented by galleries at art fairs are increasingly becoming something like conceptual statements that are very far from a simple selection of art works mounted on a white wall. For instance, many responded quite emotionally to a fragment of the booth of the Brussels Meessen De Clercq gallery ‒ two walls facing each other a metre or two apart, the display on each of them seeming to mirror the other perfectly. The works were actually created by different artists and, on closer inspection, turned out to differ in some of the details (which means that they were not exact copies of each other).

Works by Jaclyn Conley at the Maruani Mercier booth. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

On the other hand, the presence of the ‘new media’ was almost unnoticeable in the gallery booths, although a special space had been allocated to a programme of video works by 17 artists under the title of SCREEN IT ‒ something more like a cosy and inviting lounge than a cinema or a screening room. The work probably featuring the most radical choice of medium was a solo project by the Belgian artist Emmanuel Van der Auwera, entitled VideoSculpture XX (World's 6th Sense). It was a space lined with screens filled with white noise and showing practically nothing, while pieces of plexiglass on special tripods around them reflected blurry black-and-white video sequences that seemed like negatives of the original image ‒ and gradually you started to discern people hurrying down a street and fragments of buildings. This piece, dedicated to the situation of total surveillance and being surveilled and based on the phenomenon of depolarized screens, was successfully sold to a Belgian collector (another copy of the work ended up as part of the collection of an art museum in Dallas; it was sold to the tune of 80 000 dollars).

Video of the work of Emmanuel Van der Auwera VideoSculpture XX (World's 6th Sense)

This project by Emmanuel Van der Auwera (represented by the Brussels gallery Harlan Levey Projects) was one of a number of solo exhibitions included as a separate section of the art fair, aptly entitled SOLO. In keeping with the tradition, the top ‒ ‘blue chip’ ‒ galleries were brought together in the PRIME section, where you could acquire works by Bill Viola, Sarah Lucas, Ugo Rondinone, Hans Op de Beeck or David Hockney. It was as part of this particular section that the Moscow pop/off/art gallery presented a solo show by the Latvian artist Andris Eglītis. The DISCOVERY section was focusing on young and less-known artists and their latest (2016‒2019) works, while REDISCOVERY was dedicated to 20th-century art that, for various reasons, had been missed by collectors and museums, although unquestionably deserving their attention. Many new names (of artists and galleries) were featured at the INVITED section making its debut at this year’s edition of Art Brussels. That is the art fair’s way of focusing on young collectors and the art that could interest them. Participation fee for this section was several times smaller: one of the invited young gallerists mentioned EUR 4000; the selection was, nevertheless, very obviously conceptually verified.

Works by Yannick Ganseman at the Paid by the artist stand. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

At the press conference marking the opening, the director of the art fair, the blue-eyed, blonde and elegant Anne Vierstraete spoke at length about the structure of Art Brussels and its offering, about the fact that 90 % of the represented artists are live and active, a third of them still under 40 ‒ that the majority of the galleries are, of course, Belgian (44 this time), followed by the French (21) and the British (14). Of the 142 galleries taking part, 70 % are not first-time participants. 27 % of the artists are women. A question from one of the journalists followed immediately: why was there no mention of the percentage of ‘non-white’ artists represented at the gallery booths? Anne started her response very emotionally; there was even a moment when it seemed that she was welling up. She spoke about a related event that had taken place in Belgium just a year ago: the jury of the Belgian Art Prize, an award severely criticised for its ‘race and gender discriminating’ approach to the selection of the candidates (resulting in four shortlisted artists withdrawing from the contest), had decided not to award the prize in 2019. From her point of view, it was a sad experience: she believed that the main criterion should be the quality of the projects, not the race or gender of their creators. She believed there should not be any quotas or anything like that, because it undermined the meaning of art itself, the meaning of this freedom of interpreting the world that was offered by art. For this reason, ‘skin colour’ had not been included among the criteria of the statistic survey.

black blue mountain (2019) by Hugo Rondione at the Gladstone Gallery stand. Photo: Sergej Timofejev

We spoke individually after the press conference, and I thanked Anne for her emotional answer: ‘executive figures’ tend to answer any sensitive questions in a completely detached manner, with ready smiles ‒ representing institutions rather than themselves. Somewhat embarrassed, Anne answered that she had been taken aback herself but that her response to these things was so emotional for the reason that she believed in art and felt incredible reverence for the work of artists:

‘I love it when art provokes me, when it moves me to the core of my being, and that is something that cannot be predicted. I deeply respect artists who help us look at things from a different angle.’

Collector Joseph Kouli runs past the work Concrete Mixer (1993) of Wim Delvoye on the stand of Rodolphe Janssen (Brussels). Photo: Sergej Timofejev

But the world is changing, and so are our habits and methods of assimilating information, including visual information. To what extent does it influence the status of art fairs and whatever happens there?

In our time, we all get extremely nervous if the computer freezes for a couple of seconds. We are very impatient in our search for information. At that, the notion of distance has all but lost its meaning for us. We can watch a live streaming of an event taking place 20 thousand kilometres from us. In our world, children are almost born with smartphones in their hands; they are constantly looking at one screen or another. We travel both physically and virtually. And that changes the behaviour of people, their habits, including their ways of buying things. For this reason, when you enter the art fair today, you may possibly not feel the same excitement and anticipation that you used to. Perhaps there is even a certain sense of déjà vu. Because you have received previews from the galleries; you have seen a lot of the art presented here on social media. Furthermore, you are already haunted by a feeling of visual overload as it is, and you have no idea how to deal with it ‒ where to store these things inside your head. And at this point, a kind of competition between the galleries starts to restore the uniqueness of the moment, uniqueness of experience that we remember from before the internet age, when people were actually in a hurry to visit the art fair and ‘see it all’.

Work by Jon Kessler Exodus (2016) at the booth Eduardo Secci (Florence). Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Yes, I did notice that the gallery booths are becoming more interesting, attracting interest with their appearance and design, the concept behind them. They are becoming increasingly more like art projects instead of collections of various art objects. And it seemed to me that this trend was particularly pronounced at Art Brussels.

Yes, of course, there is this necessity to stand out, to be noticed, to catch the eye of someone passing by the booth. For instance, a very new gallery from Brussels (Damien & The Love Guru) did the opposite ‒ they closed off their space, fenced it off with wooden panels. So you need to walk in, to enter the booth to see the actual works. I think that this ‘dissociation’ works in the opposite way, it looks inviting. When everything is open, you pass by, automatically thinking: aha, aha, aha, whereas here you take a step towards the art just to enter the booth. I think that a certain role is played here by the fact that in our case, where the art is really contemporary and the artists are alive and active, this means that they are directly involved in the process of presentation; the artists are often ‘curators’ of the gallery booths.

Performance of Anne Rochat at the Counter Space booth (Zurich). Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Also, there was this trend of a huge diversity of media in a single presentation that was very noticeable in the gallery booths. It is this play on volumes, forms, angles, refractions that the screen of a computer or a smart phone is ‒ as yet ‒ unable to deliver.

Of course! There is a lot of play on all of this. A total diversity of formats ‒ performance, video, photography. This year there is quite a lot of work done with textiles, where we sort of see a picture in front of us, but it is actually not a painting, it is a textile. Another exciting trend ‒ ceramics, traditionally a craft format, and yet here it is presented as objects of contemporary art. That is, for instance, how the Vietnamese artist Bui Cong Khanh, represented at the SOLO section, works: it is a traditional technique, enriched with contemporary conceptual vision.

Basically, you are not going to get bored here. In this sense, with all due respect to our rival art fairs, what we often see there is exactly what we expect to see. Here we always strive to achieve a good dose of the unexpected. And it is a real compliment when someone says later that ‘I discovered this artist for myself’ or ‘I discovered this gallery for myself’… It is a genuine recognition of our work, our committees and experts. We tour various art fairs; it is the ideal platform for gathering information, but we also try and visit galleries in their own space, because that helps achieve a different quality of dialogue and perception.

Works by Hans Op de Beeck at the booth of Ron Mandos (Amsterdam). Photo: Sergej Timofejev

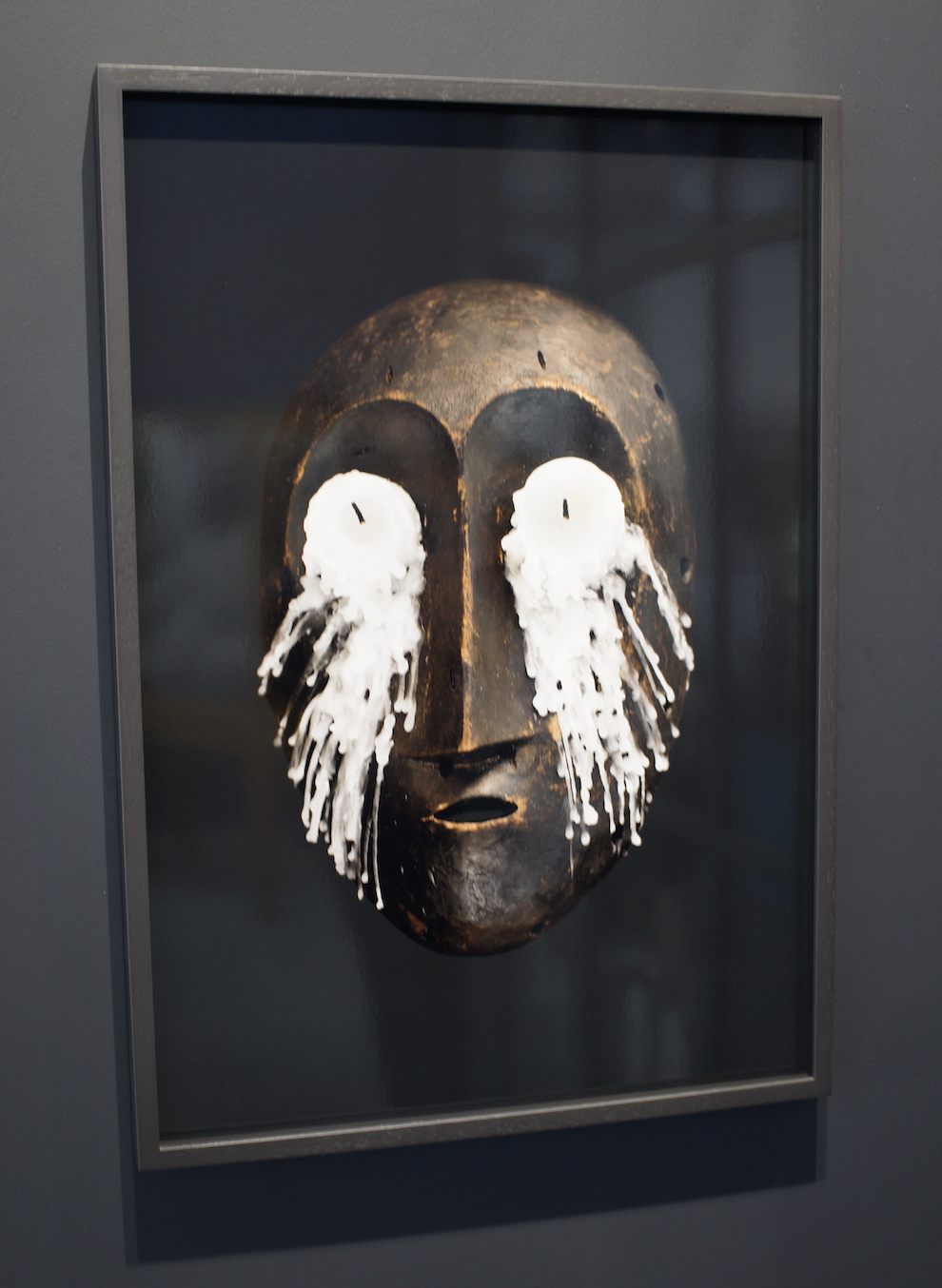

It seemed to me that there was a lot of works rooted in traditional African art at Art Brussels that were also reinterpreting it in a contemporary format.

That is a global story, I think. There are art fairs specialising in African art, like 1-54 in London. It is genuinely the legacy of the African traditions, evolved to the contemporary art scene. And this art is increasingly attracting attention. However, to sort of continue the subject of the artists’ skin colour, I do hope very much that in a number of years’ time the very question of a necessity to emphasise these differences will already belong to the past. Whatever kind of artist you are, wherever you are coming from, you will always have your own personal little ‘rucksack’ in which you carry your heritage, your roots ‒ where you are coming from, what your family, your culture means to you. And it is only natural that it becomes part of what you express in the language of art. But is it that important what the colour of your skin is?

The work of Thierry Fontaine from the Collection (2017) series at the booth Les filles du calvaire (Paris). Photo: Sergej Timofejev

There is this old adage that ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’. I think that it could be very well applied to the Brussels public. There are so many galleries of traditional Oriental and African art... People have become accustomed to these things, they have seen a lot of that; for the local public, there is nothing exotic about it. And that is why the next step ‒ rethinking this artistic language in a contemporary format, ‘estranging’ it ‒ seems very organic here.

Yes, of course, because we had this colonial past. Here we have had and still have quite a lot of significant collections of this kind of art, and therefore there has been interest in this kind of artistic expression.

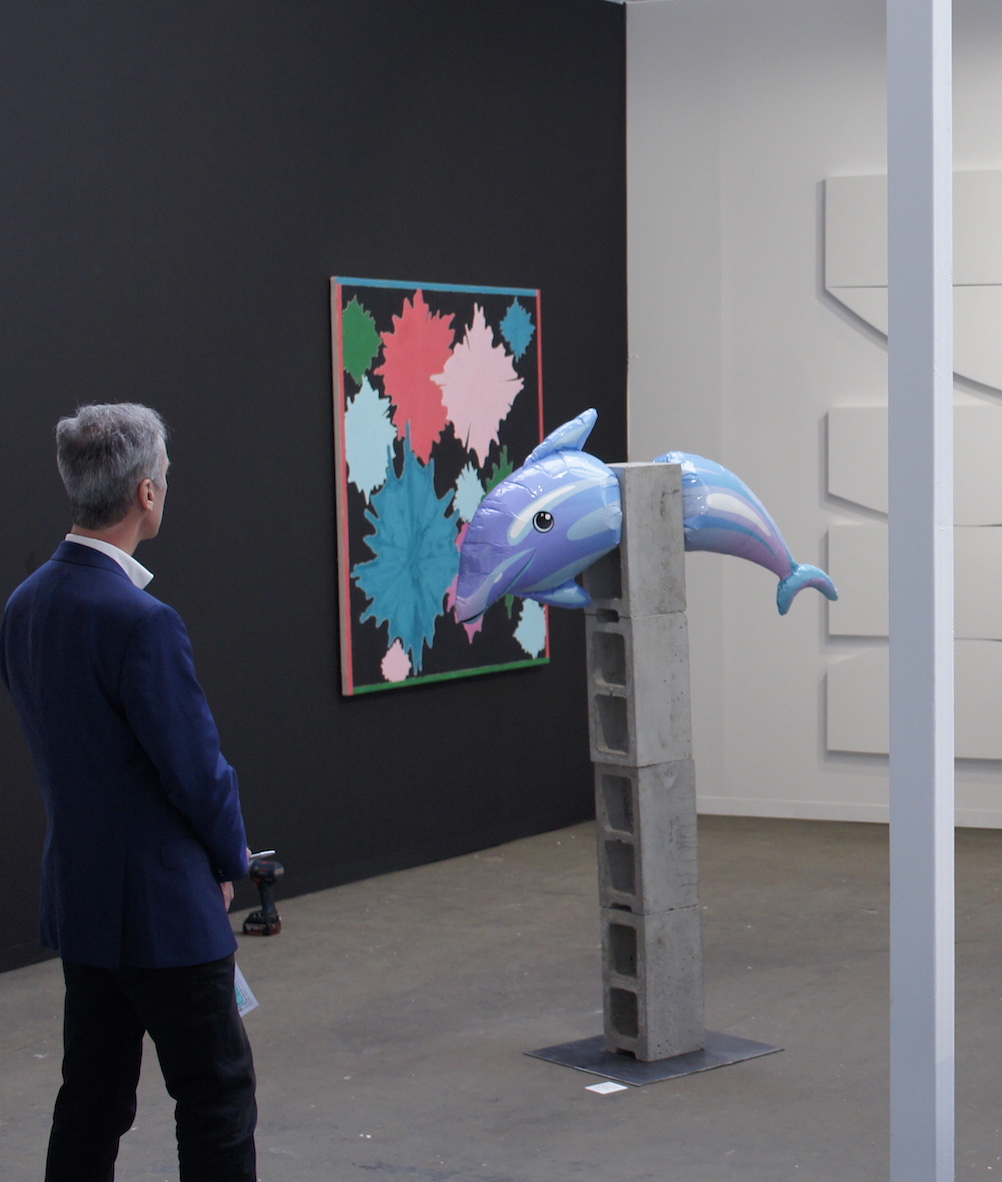

At the booth of The Hole (New York). Photo: Sergej Timofejev

How would you describe the average Belgian collector ‒ what is he or she like? If you tried to personify...

It is someone who is very well educated and knowledgeable in art. They could be described as an intellectual collector. They like to present to the world new talents, to notice an artist in the early stages of his or her career and start to support them by purchasing their works. And they are very open. At that, they do know a lot about the actual process of collecting...

Visitor at the stand of Meessen de Clercq (Brussels). Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Yes, it seems that the culture of collecting is, in some cases, handed down from generation to generation.

Yes, it is true. And we take good care of our new generation of collectors who have a completely different approach, because these people were formed by the age of the Internet. We think about future editions of Art Brussels when the present generation of collectors will have left the stage. And that is why it is also the general public that is important to us, not just art collectors. We organise free guided tours of the art fair, because the world of contemporary art does require a certain ‘key’. We try to provide these keys, try to educate the public. Because it is the best way of arousing its interest later. And it is important for us to bring together young collectors and artists who belong to their generation.

In what way is this generation of collectors different in your opinion?

It is not from books on art or not just books that they obtain information. They obtain information everywhere, on social networks and so on. They are much more used to abundance of information; it is the norm for them. And that is why it is so much more difficult to make them ‘bite’, to catch their interest.

At the stand of the Sorry We’re Closed gallery (Brussels). Photo: Sergej Timofejev

Almost a ‘mission impossible’. Interestingly, not so many new art formats seem to emerge despite all that. And the ‘new media’ are no longer particularly new.

Yes, but the ways of using them, playing on them ‒ they change constantly. I remember the time when mobile phones first appeared, I asked myself then: ‘What for?’ The same thing was when they started building cameras into phones. Today, no-one even questions it. It has become almost a part of ourselves; we use this feature every day. But once we have taken these pictures, we no longer look at them, and that says a lot about us. We no longer compile these albums that we used to have in every home since my childhood. The pictures we take today seem to possess a different value than the ones taken some 15 years ago. For young people, on the other hand, it seems completely natural; they do not compare this with other times. And art galleries, of course, sense this, they try to react to this, and that is why it is so important for them to attract attention, to elicit a response from the viewers.

Anne Vierstraete at the Art Brussels 2019 press conference. Photo: Sergej Timofejev