The shy boy in the corner

An interview with Estonian painter Kaido Ole

11/06/2019

The exhibition Kaido Ole: Dance at the Lonely Hearts Club is on show at the Arsenāls Exhibition Hall until August 25.

The exhibition is almost ready, but there are still several days until the opening. Estonian artist Kaido Ole is directing all of the work himself. He’s dressed smartly for our interview, in white trousers and a dark blue shirt. First he takes me on a short tour of the two huge spaces at the Arsenāls Exhibition Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art, where his Dance at the Lonely Hearts Club retrospective solo show will soon open. As we come at the paintings containing references to familiar stories, he says, “Painting is a good way to tell stories. You can put yourself at the centre of the story!”

One of his paintings depicts a photo of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin’s famous log. Seeing that I recognise the reference, Ole comments that people who are younger than us don’t understand it, and the joke must be explained to them. So, let’s recount the legend: the leader of the proletariat was participating in a volunteer clean-up event at the Kremlin and posed for a photographer by joining a group of people carrying a log. After Lenin’s death, huge numbers of people came forward, saying that they had been there with the leader and carried the log along with him...except that they were at the other end of the log, which cannot be seen in the picture.

Ole speaks eagerly, openly and with wit. As the interviewer, I can guarantee that I am not to credit in this regard. For example, I don’t know why he starts telling me about his sex life – I swear did not ask him about that! Ole’s paintings are full of his personality; they are entertaining, vivid and moving.

All together III. Canvas, oil and acrylic. 295 x 275 cm. 2019. Property of the author.

Do you always participate in the setting up of your exhibitions?

I usually do everything myself. I’m a so-called control freak. I’m not very good at working in a democratic manner, through discussions and talking things over. But I am polite – I want to be good towards other people. So it’s good if we can agree in the beginning that “alright, this is my sandbox, and this is your sandbox”. Then everybody’s clear about where things stand. Even if I don’t like something, it’s all been decided on beforehand.

For example, this exhibition is, on the one hand, my own retrospective, my self-portrait; but on the other hand, it’s also Māris Vītols’ exhibition, his work as a curator. It’s his idea. So it’s important that we had these conversations. His personality differs from mine, he has different interests, a different focus. As he uses my artwork, he also explains his own way of thinking – he divides the work into narratives and selects the headings. But that’s not a tragedy, because no one can feel things the same way as I do, just like no one can be exactly like Māris; we’re all individuals. It’s simply that this is becoming more publicly visible right now.

But in any case, there’s no way I can know what’s going on in the heads of the visitors who come to my show. Each person understands my works of art differently, and no one understands them exactly the same way as I do. And that’s OK. But I’m not saying that I perceive that lightly. Perhaps I could compare art with programming – I offer it to others, but each person can use it as they wish. You can’t just live in your own little bubble; I can’t constantly monitor that everyone uses my creations only in the way that I’ve intended them to be used.

Because that’s not possible…

Many artists say – not only say, but also believe – that they make their viewers think. But that’s a position of power, like in school, where one person is the teacher and the others are all students, and the teacher knows what the students should be achieving. I hate this phrase. I don’t like it when someone tries to make me think. I think all the time, constantly, and I think the way I want to think! An artist can only put something in front of me, leave it on the table, and if I like it, I’ll take it. I’ll use it how I want to use it, not how you tell me to use it! C’mon, who are you? I don’t like the didactic attitude at all.

When the museum began working with this exhibition, I met with the technical team – a very nice group of young men. They were unpacking my paintings in a completely different way than I usually do it. Usually I also unpack my own work, but this time I didn’t have the time – interviews and things like that – and I arrived as they were already taking off the plastic wrap. “Wait, wait!” I wanted to call out. But I bit my tongue and put my trust in them. And they did the job well, just differently than I would have done it.

Did they damage anything?

No, everything went well, just in a different style. I’m probably too careful and think that I’ll do everything better myself. But they’re not the same people as I am. It was a lesson for me.

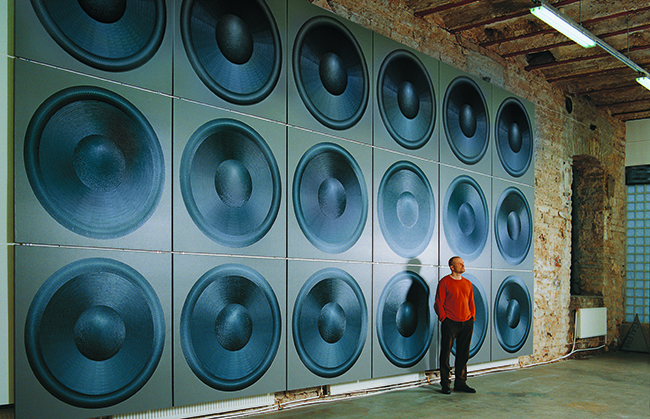

The Band. Exhibition view. Vaal gallery, Tallinn.2003

How did the idea of having a retrospective in Riga, in Latvia, come about?

Someone already asked me that, and I realised that I don’t even really remember. I met art collector and curator Māris Vītols after he had already acquired several of my works. That’s where it all began. We talked about various different spaces, including Riga Art Space and the Arsenāls Exhibition Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art. I’m really happy that we ended up at Arsenāls, because I like museums. Really, I do. Maybe younger people, people of “street fighting” age, don’t like museums because they’re so traditional; they’d rather show their work in garages. But actually the museum is the institution that really cares about art. Even if the people who work there are poorly paid and unsatisfied, they still preserve the art.

As I was preparing for this exhibition, I had to turn to several art institutions in order to borrow works, and I saw that that isn’t always the case. At some collections the personnel has changed, and the new employees have just moved my work to the warehouse and haven’t paid any more attention to it. It might even be damaged. But that will never happen in a museum! Museum employees are truly my kind of people. They know a lot about art, they know what to do with it. I feel at home in museums.

It’s also nice to have work in private collections, to know that my paintings are hanging on the wall of someone’s home. But who acquired them is important. If that person dies, it’s possible that his or her children aren’t interested in art, they sell the piece, and then it might get lost, no one knowing what’s happened to it. That’s very sad. But in a museum, that same work of art will still be there a hundred years from now, and that means a lot! The fact that I made a lot of money twenty years ago by selling some work of mine – that doesn’t mean anything at all today.

When I asked you in the exhibition whether you like to dance, you said that you don’t dance at all.

To be more precise, I don’t know how to dance. I think that I like to dance, and I really like it when other people dance and I like watching them dance. But I don’t know how to dance.

But when there’s music playing at a party, you move to it somehow, don’t you?

I move when I’m alone in my studio and there’s music playing. Back when I was a teen and the only way to meet girls was to go to the discotheque, then I had to dance. It was like a ritual. Of course, I danced back then, but I was an awfully bad dancer. I had no confidence on the dance floor. I think the main issue is that I don’t trust my own body. The only movement that I know how to do reasonably well is walking down the street, properly dressed.

That’s why clothes are so important for me. They cover my body and make it acceptable to myself. I don’t like my body when it’s naked, and I don’t trust it. That’s also why I don’t swim or sunbathe; I don’t like beach culture. When I’m undressed, I don’t believe in myself. It’s the same as with artwork – I might believe in one piece but not another. And it’s similar with bodies.

Of course, it all began in my teenage years, the age when you realise that you’re someone with a body, and you gain a new point of view about yourself. Dancing and swimming are closely linked with a person’s appearance, with how he moves. Of course, everything depends on perception, because when you look at the kind of people relaxing on a beach, you wonder whether it wouldn’t be better for many of them to be dressed. But they’ve got no problem with it. So that’s my problem – I feel like I’m not good enough. I’m not good enough to undress, I don’t move well enough, I don’t look good enough. I’d actually agree to act in a porno film if my body was a little better! But not now.

Ballheads III. Untitled CLIX. Canvas, oil. 200 x 190 cm. 2000. Private collection.

Does this somehow manifest itself in your paintings, for example, in self-portraits or paintings depicting a penis?

I trust my feelings when I’m thinking about whether I can put this or that on a canvas. And if this feeling is positive, then I go ahead and do it. In general, I think that... Back when I was a teacher and asked my students why they did something this way or another, they very often just answered that they liked it that way. And I said no, that’s too simple an answer; analyse it a little more! “Liking” something doesn’t mean anything. But now I confess that I, too, do lots of things because I like them that way, and that covers a lot of ground – so many different reasons that if I began listing them all, I’d only get to about half of them. But I’m not convinced that I could even name the most important reasons. They’d just be the first ones that come to mind. So I choose the easiest route by simply saying that I like it that way. The feeling has to be clear and strong.

I also believe that a good work of art is always wiser than its creator. Even Picasso’s best works are wiser than he was. You can’t always plan everything out. In the best case, you can plan about half, and then you have to start flying – that’s when the artwork begins educating the artist.

That’s why all those naked and sexual scenes – sometimes they’re just a desire to be attractive, but in part it’s also true that I have problems accepting my body, and I also think I’m pretty bad at sex. I don’t know how to let my “inner beast” loose at the right moment; I control it too much. But then in other situations – usually very stupid ones – the beast comes out on its own. I’m even ashamed of myself sometimes when I’m driving my car.

You yell when you drive?

Yes, I yell and am aggressive, I drive too fast and so on. And I can’t control myself then. It’s strange – I often surprise myself. But over time I’ve understood which things I can change and which ones I can’t change. That’s the way it is. I think the main thing is to be friends with yourself. I think a lot of people aren’t friends with themselves. Even if I sometimes don’t like my body, I like the shy boy who lives inside it. The one who doesn’t know how to dance and is bad at sex. In a way, I like losers, and I like the loser in myself.

For example, exhibition openings – obviously, a lot of important people go to them, and I should be shaking hands with notable curators. But I don’t like doing that! I’d rather find someone sitting in a corner. My colleagues say, “Why are you talking with him, there’s no point in it! You need to talk to that big curator over there.” But I don’t like talking with that big curator, because I know why I’m talking to him: he might include me in an exhibition in New York or something like that. I need something from him. But the guy in the corner is just a simple, normal person. Of course, I’d like to show my work in New York, I’d like to be part of an exhibition at MoMA. And maybe the curator is a good person, but there’s always something between us. Sometimes I hate myself after conversations like that with big curators. It’s like a form of pornography.

Ballheads IV. Untitled CLIX. Canvas, oil. 200 x 190 cm. 2000. Private collection.

If you don’t dance, how did you arrive at the title for this exhibition? Of course, the Beatles’ song, but what else?

I offered the curator several different titles until we finally settled on this one. Curators are often interested in social and political issues, ways in which art helps to make the world a better place. This is done quite directly in contemporary art: you notice a problem and you offer solutions. But I don’t really believe in this approach right now, in this period of my life. It looks effective, but it isn’t. I believe in quality: if you do something truly well, then this quality lifts people to another level. They become better people instead of just learning to either do or not do this or that. Politicians and policemen talk to people in a similar way. But the question of how to become a better person? You can feel it after listening to a symphony or seeing a good exhibition.

A little bit about the formal side of your work. Latvians often call you one of the heirs to Estonian pop art – either because the Estonians have such a tradition, or because we do things differently. Is that completely wrong?

My work form the 1990s, which is not included in this exhibition, is perhaps more pop-y. I’m a big fan of pop culture, but I don’t worship Andy Warhol and other pop artists. But there’s another thing that might make them say so: my style of so-called hard-edge painting, the geometric forms. Those are important to me. It has to do with my character as a control freak. Hard edges are the only form that corresponds to me; I really enjoy it. I do have a few more expressionistic works, but they’re more like jokes. I’m also not very good at expression; I can only pretend. But people who are truly expressionists cannot paint with hard edges. Actually, there’s not a big difference between expressionistic painting that looks more natural and very controlled painting that looks less natural; it’s important to simply turn your more sensitive side to the world. Then you can obtain information, feel what’s happening on the outside and vice versa – what’s happening within you. I know very clearly that I cannot paint as precisely as I’d like to, but on the other hand, painting is the manifestation of an individual person. And man is a weak being. I can be as good as I can be, but a painting also contains signs of my weakness.

We’ve been talking about very serious things, but I found myself constantly smiling in this exhibition. It seemed light.

I’ve already heard that before, many times. This “don’t laugh, he’s actually talking about serious things”. That also happens to my friend Marko Mäetamm at his shows – everyone who goes to see them becomes happy, there are always fun conversations and so on. Because he’s even a bigger clown than I am, even if he’s in fact suffering. But you don’t notice it: even though his work depicts terrible things, half of your face can’t help but smile! Because he has a talent for that.

But I think that’s really great, because only that way is there any hope of surviving. Even if things are shitty, it’s possible to smile about them. Marko and I have the same sense of humour; we could even finish each other’s sentences if need be. So, if you say that my show seems light, then I’m a similar case. I can’t change that fact, and there’s no use in trying. I’m not going to tell you, “Stop smiling, this is a serious exhibition!”

At the Art Exhibition. Canvas, oil and acrylic. 240 x 190 cm. 2015. Property of the author.