A life spent trying to get closer to Rothko

An interview with Brazilian artist Marco Giannotti

Ivonna Veiherte

02/08/2019

Several new exhibitions can be seen at the Mark Rothko Art Centre in Daugavpils, including Passages, which will run through October 30 and is a showcase of paintings by Marco Giannotti, a professor at ECA/USP – School of Communications and Art at the University of São Paulo. It is important to note that also a new permanent exhibition of Mark Rothko's works has been created and will be displayed in Daugavpils over the next three years. On the opening day of this new exhibition, July 12, Giannotti and noted scholar and art historian Dr. David Anfam (London), author of the Mark Rothko catalogue raisonné, participated in the public talk Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue? on Rothko's creative work and its context.

Giannotti is known not only for his paintings but also as a teaching professor and the author of several books. In 2008 he was a visiting professor at Yale University and spent 2011-2012 in Japan, where he taught at the University of Foreign Studies in Kyoto. His works have regularly been included in major national and international exhibitions, such as: Contemporary Art São Paulo: recent perspectives at the São Paulo Cultural Centre (1989); Panorama of Current Brazilian Art at the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art (1990 and 1993); and Art/City: city without windows (1994); he has also participated in both the second and third editions of the Mercosul Visual Arts Biennial (1999 and 2001) and in the Cuenca Bienal in Ecuador (1987).

My conversation with Giannotti took place a few days after the aforementioned public talk. I will not hide the fact that one of the reasons for this interview was also the hope that during our conversation, Giannotti would utter some ‘key words’ that would perfectly explain the sublimity of Rothko in a few sentences – for the simple reason that I am so often asked the following question: What is it about Rothko’s paintings that has placed them in such high regard? Admittedly, I haven't come up with anything better than the rather obtuse ‘you just have to stand there and look deeper’.

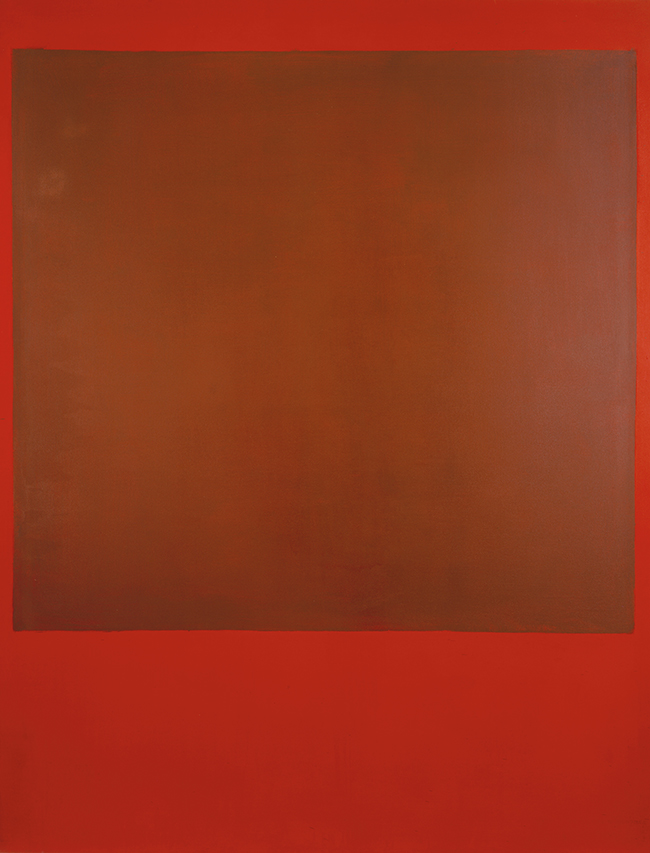

Mark Rothko, UNTITLED. Canvas, oil, 1964. 228,6 x 175,3 cm

How did you come to take a more concentrated interest in the art of Mark Rothko?

As a teenager, I lived in New York for a couple of years. My school was the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where I’d go several times a week. At the Museum of Modern Art, in the large room dedicated to Rothko's paintings, I began to understand abstract expressionism – and in some sense, Mark Rothko became my spiritual father. I was particularly interested in the ‘colour field’ direction of abstract expressionism. I saw it as an expression of spirituality. I developed an interest in colour theory. Moreover, not only in terms of colour as an intrinsic value or as a benchmark and its importance in depicting perspective, but also in terms of expressing human emotions. I thought about the mutual relationship between colours and a painting, and about the role of colour in architecture.

Rothko spoke about creating a new, subjective space. Perhaps that is why, for example, the Japanese understand his paintings better. I have spent my life trying to get closer to Rothko. I am amazed by him.

Rothko did not use perspective. His only form of expression was colour – yet never pure colour.

I am also interested in the size and composition of Rothko's paintings, which are proportionate to human height. In its own way, the horizontal division imitates the head, body and legs. (David Anfam. Mark Rothko: The Works on Canvas Catalogue Raisonné).

How crucial or decisive is it to have a background in art history in order to understand Rothko? In your opinion, do you think it is easier to grasp his art if one is aware of his creative path – the evolution of his work from surrealism to a simplification of form?

Before World War II, Europe was dominated by surrealism and concreat art. Many notable European artists came to New York during the war – such as Duchamp, Breton, Mondrian, and others. Also returning to New York was Peggy Guggenheim, whose husband Max Ernst encouraged her to support these artists. She was the first to buy Jackson Pollock's works, for instance. I believe that in the 1950s, the two directions of abstract expressionism (action painting and colour field) combined all of the previous achievements of the 20th century. Here there was both abstraction and rationality, lyricism and precision, as well as the opposite – subjective expression. Abstract expressionist artists were capable of capturing and combining the best of each previous art movement – both metaphorical and concrete surrealism as well as new abstract forms.

The emergence of completely abstract forms back then, in the 1950s, was something new and unprecedented. Abstract art can be powerful, human, and, like great music, can evoke such strong emotions that it can make you cry.

Artist (on the right) with Dr. David Anfam at the Mark Rothko Art Centre in Daugavpils on July 12th

Rothko's works require a sensitive viewer. Do the people of today lack the time necessary for proper perception and contemplation of Rothko's work?

Yes, it is important to note that everyone is short of time today, and contemplation is increasingly becoming an obscure thing to do.

One must look deeply into the paintings of Rothko. It’s simple – the more you look, the more you will see. What really matters here is the purely human experience of the viewer himself. Feelings need to be nurtured. A child simply needs to be taken to a museum. If all she eats is McDonald's, it will be difficult for her to appreciate anything of more substance. In today's world, young people are reading less and the whole education system has also changed. In working with students, I also show them pictures on a computer, but what is truly important is for them to have the museum experience where they can get a direct impression and understanding. Education is decidedly crucial, but culture is not being given enough space in it. This is a social responsibility. For instance, when Beuys worked with students in Germany in the 1960s and 70s, it was sometimes difficult to distinguish between his lectures and his art. All children love to draw. What is bad is when around the age of seven or eight, the teacher tells the child that she is ‘not drawing properly’, or to colour only within the lines. As a result, the child may no longer find joy in drawing. The desire to express oneself may also disappear.

We are talking about the greatness of things or their magnitude. The academic style of the late 19th century in which everyone did the same thing, i.e. drew Greek statues, left a strong impression. Courbet also participated in an exhibition of academic painting. Now everyone loves Monet, but in his day, his style of painting was not accepted. Everything has its time. You cannot understand an artist or develop your artistic perception without knowing the history of art. Even Rothko, like all the great painters, always talked about that. Why is it so important today? Because painting no longer needs to be academic, and in place of using academic reasoning, we are more driven by our feelings.

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1948. Canvas, oil. 127,6 x 109,9 cm

There is still the risk of ascribing the function of purely decorative art to Rothko and other abstract expressionist painters. How would you argue against such a misunderstanding?

The term 'decorative' has many definitions. In the East, 'decorative' is a fundamental concept. Mosques, textiles and carpets are examples of this. Eastern art has always influenced the West. For example, Vincent van Gogh's passion for Japanese art. They had completely different criteria, e.g. space without perspective, and as a result, colour became a stronger medium of expression. In the same way, one can also talk about colour being a feminine element of artwork, but design as a masculine part. Today these old relationships are no longer accepted – colour and design are becoming more independent of each other. Absolutely everything is important.

Being fully knowledgeable about your craft is always essential. At the age of seven, Leonardo da Vinci was sent to work for an artist to learn how to prepare paints. In contemporary art, technique and professionalism are no longer relevant criteria. That’s why Hirst can be lauded for a perfectly executed work even though it was in large part made by Chinese workers. For his larger works, Rothko, for example, used a medieval recipe for rabbit skin glue because of its special technical qualities. He was a principled artist and opposed to the idea that his works should fulfil a purely decorative function. There is the case in which he changed his mind about a commission and reimbursed the Four Seasons hotel restaurant the 35,000 dollars he had already received in advance. This happened in the late 1950s. [These are the legendary large-scale Seagram paintings that Rothko worked on for the Four Seasons, a commission which he canceled after having eaten lunch at the restaurant – Rothko stated that he hoped ‘to ruin the appetite’ of everyone eating there. The paintings were stored in a warehouse and several years later, gifted to the Tate Gallery. Through June 30 of this year, an expansive Mark Rothko retrospective was held at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna; it included the Seagram series, which was on view for the first time in continental Europe. – I.V.]

You have translated Goethe’s Theory of Colours (Zur Farbenlehre). What role does this book play in understanding Rothko's art?

I translated Theory of Colours from German to Portuguese in 1993. Back then it wasn’t as popular a book as it is today. Goethe talks about the perception of colours and the fact that they have more than just an optical meaning. He thought that Newton was mistaken about the physics in terms of colour waves. This material is interesting to study. Both Newton and Goethe are right.

Knowing colour theory can also give you a better understanding of abstract painting. Art can become an abstraction if you study colour and light as abstract elements. Abstraction is also one’s inner experience. For example, green is not a reference to a part of the landscape but simply the colour green. If the opposite colors , red and blue, for example, are close , they are very powerful, but when mixed, they become grey.

Thinking in this context, the first major avant-gardist was Turner, who was also highly respected by Rothko.

Mark Rothko, Self-portrait. Canvas, oil, 1936. 81,9 x 65,4 cm

The permanent exhibition of Rothko's works at the Rothko Centre has undergone changes.

On view is the powerful, Rembrandt-like self-portrait from his early period. A transitional ‘multiform’ painting is on display, one in which surreal forms disappear as if in abstract configurations. You can also see the red work created in 1964, which is when the so-called ‘multiforms’ acquired a connotation of space and light.

You yourself have been painting for over thirty years.

Structure is important in my works; the interaction of drawing and colour is important – the painting is inconceivable without it. Likewise with architecture. I am interested in how a two-dimensional painting can become three-dimensional. This means – how is space represented. I have always been fascinated by the metaphor of a window; that is my conceptual foundation – a painting is like a window. I want to get to know a sense of mystery. A closed window makes you think more about your own experience and feelings. Today's new window is a cell phone screen on which all images can only be two-dimensional.

I have recently also begun to use compositional structures to address the issue of perspective. I’m experimenting with aerosols, but in a different way than graffiti. I’m interested in the work surface and how sprayed paint creates new structures when combined with oil.

Exhibition view of paintings by Marco Giannotti, Passages, at the Mark Rothko Art Centre in Daugavpils