‘We arrive at the indisputable factuality of a pit with human bones.’

A conversation in Lviv with the Ukrainian artist Nikita Kadan

Galina Rymbu

17/10/2019

Nikita Kadan is one of the best-known young Ukrainian artists. He often has exhibitions outside Ukraine (2019 ‒ MUMOK, Vienna; 2016 – Galeria Arsenal (Białystok); 2015 – Waterside Contemporary (London), etc.). Born in 1982 in Kiev, he still lives and works in the Ukrainian capital. Nikita is a member of the R.E.P. group of artists and the Khudsovet curatorial group, recently taking the post of the head of the contemporary art department of the Kmitov Museum of Fine Arts. Kadan graduated from the National Academy of Art and Architecture in 2007; in 2011, he won the PinchukArtCentre Prize and in 2014 ‒ the Special Prize of the Future Generation Art Prize contest. He represented Ukraine at the Venice Biennale in 2015.

Kadan’s works deal with politics, memory, propaganda, ideology, history, mass political violence and trauma. He profoundly reflects on the present state of the post-Maidan Ukraine, speaking about the country’s current historical policy, about the ‘memory wars’ carried out there today and about the possibility of personal tuning in to a collective traumatic historical experience. The artist defines his practice as part of the art of the historiographic turn, exploring not so much the actual history and its facts as the structure of historical narratives and ‘ways of telling history’. This summer, at the time when Nikita Kadan’s latest exhibition, dedicated to two figures of the Soviet Ukrainian avant-garde, Vasyl Yermylov (1894‒1968) and Ivan Kavaleridze (1887‒1978), was already open at the Vienna MUMOK, we met in Lviv to speak about the make-up of the current Ukrainian art scene (most processes, artists and institutions of which are regarded quite critically by Nikita), his works and exhibitions of the recent years and reasons why feminist and queer sensibilities are important for contemporary art today.

We were sitting at the Pyana Kachka (Drunken Duck) bar/art gallery, the Laboratory of Paranormal Phenomena exhibition looming white behind our backs. I was equipped with Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others, Nikita ‒ a folder of his own drawings. This was our first meeting, although I had been aware of his work since 2010, when I saw his ‘schemes’ in the leftist literary-critical anthology Translit. Conversation with Nikita is a complex and unhurried critical journey; the turn of his phrases is simultaneously exact and capacious, at times even harsh: ‘is “self-organisation of memories” possible?’; ‘violence will be given various names; at that, these names will often be given to clear the way for still more violence’; ‘let the dead revolt against absolutely any form of ‘patriotic exploitation’ of their death’, etc.

This sharp needle of artist’s critical reflection and thought, hitting the historical nerve unerringly, keeps bothering the familiar categories and narratives, because there is no greater disaster than ‘history’s sleep’. We started with a critique of the current Ukrainian art scene, eventually moving on to his Pogrom series based on photographs of the Jewish pogroms in Lviv [in 1941], and at some point he said: ‘This could have happened right here, at this very spot where we are sitting now, on this pavement. And it could have come as something nameless.’ Time has turned upside down.

Nikita Kadan. Photo: Taras Gritsyuk

Ukrainian contemporary art – what is it like today? How has the Ukrainian art scene changed after Maidan and during the war? What is the role of art in the Ukrainian society of today?

I must warn at once that my position is an extremely politically engaged one. I don’t claim to be capable of a cold and detached view. Art scene is a battlefield, just like the public sphere in general. That is why in a conversation about the Ukrainian art scene I choose to express a polemic position instead of a corporate interpretation of the common cause.

The Ukrainian contemporary art scene survives in isolation through building an autarky, both in the conceptual and infrastructural sense. Internationally working artists are outcasts in Ukrainian art. On the other hand, when the number of outcasts is big enough, they can build a sort of parallel scene. At home they are a semi-underground sect with an extremely limited access to domestic resources but with a window to the outside world. Anything ‘leftist’ or ‘queer’ is ‘alien’ for Ukrainian art. Mainstream art is still feeding on the leftovers of the ‘post-modernist 1990s’, which have transformed into something quite conservative.

For the general public, mainstream art becomes noticeable when it is allocated a place either in the entertainment industry or in projects of ideological service; in the past it was, for instance, pro-Russian Orthodox Christianity that was served, later ‒ nationalistic patriotic propaganda. As for ‘the alien’, it becomes visible when there is news about yet another demolition of an exhibition. This watershed existed long before Maidan, back in the late noughties. After Maidan and since the beginning of the war, two parallel transformation regimes emerged. The following took place in mainstream art: reasonably apolitical artists, experiencing a citizen’s impulse, temporarily changed their range of subject matter without reconsidering their language. That was how a lot of non-critical, affirmative yet politically engaged art was born. On the other hand, the art that saw itself as political before the events of 2013‒2014 acquired a certain historical dimension. Departing from, relatively speaking, ‘activist’ or ‘journalistic’ approaches, this art started viewing current events within the logic of their historical development. In the former case, there was eventually a return to regular apolitical practices; the wave subsided. In the latter case, the new trend formed a Ukrainian version of the global ‘historiographic turn’.

Red Hills. 2019. Concrete/metal. Installation view at MUMOK, Vienna.

Tiger’s Leap. 2019. Iron

You are well-known and shown in Europe. But how do you build your cooperation with Ukrainian state-owned and independent institutions?

There is less and less Ukrainian state institutions in my life. Some of them probably avoid politically unreliable statements. Others find the production side of my work burdensome: after all, these are mostly installations behind which there is also a lot of research. The third kind of institutions are populated by figures from their unions and academies, or perhaps the ‘1990s heroes’ who have settled down now: they undeniably feel deep dislike for our circles. In any case, over the recent years I have received a number of proposals by state institutions; however, something inevitably went wrong during the process of working out the details of the project. The (Un)named exhibition at the National Museum of Art in Kiev did not take place. A project by the R.E.P. group dealing with the legacy of Heorhiy Narbut from the 1910s‒1920s that was to be shown at the same museum also didn’t happen. At the same time, my Project of Ruins opened at the Vienna MUMOK and works from the (Un)named show were on view at Never Again in the Warsaw Museum of Contemporary Art.

As for independent institutions, my experience of working with the Centre for Visual Culture in Kiev and Centre for Urban History in Lviv was a very good one. However, they really are absolutely not capable of permanently supporting the practice of any individual artist in Ukraine. In general, in terms of economy, the division into socially critical and apolitical art has led to gradual displacement of the former by the latter ‒ but that is only true at home, in Ukraine. With Evgeniya Molyar and Leonid Trotsenko, we are currently working on an experimental programme of contemporary art shows for the Museum of Fine Arts in the town of Kmitov. However, it is an institution that has completed its initial mission, and now this museum needs to be reinvented, recreated. The museum is also under attack from the local ultra-right politicians, focused on our study of Soviet art and the neutral use of the term ‘Soviet’ by us.

From what you have said, it becomes obvious that you have a somewhat complicated relationship with the Ukrainian art scene and many Ukrainian artists of the older generation, the ones you refer to as ‘the heroes of the 1990s’. Why has it happened like that?

Many of them have become conservative, and for them a leftist political stance and also queerness and (pro)feminism are something viscerally alien to them. They feel that it is something quite different, perhaps something aiming to displace them, so they treat it extremely jealously. Besides, in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, they had high hopes for an international presence, which is practically non-existent now, whereas younger artists, either queer or leftist and involved in the ‘historiographic turn’, are internationally active. And that creates additional ground for conflicts. However, this could lead to a subject that is much more interesting than conflicts and division inside one of the Eastern European art scenes. A subject with much greater potential is the thought that contemporary art per se has squandered, lost its contemporaneity. Whereas the selfsame queer-fem-activists feel the logic of historical development; they hold contemporality in their hands.

Contemporary art, on the other hand, particularly in its post-Soviet incarnation, has lost touch with contemporality; it has been simply marking time. The post-Soviet version of contemporary art, on one hand, imitates certain successful examples of international art life; on the other hand, it is quite limited and defined by local social habits and means of articulation. Ukrainian artists of the previous generation were good at deconstruction of ‘the great narratives’ of the past, but the farther we depart from this past, the more decorative these practices become. The 1990s artists knew how to ‘shock the philistines with perversions’, but the things that were perverted and shocking in their book are simply a way of life for younger artists: queerness instead of perversion. It is one thing to crush normativity and completely another to recognise its artificial nature in a calm and composed manner and give it up as redundant.

Could you name some of the interesting young Ukrainian queer and feminist artists? To what extent are they part of the institution?

Oksana Kazmina; Antogina; Alina Kleitman; the Praktiki Tela project; Dana Kavelina; Velentina Petrova; Anatoly Belov. There are actually not many of them, of course, but they make powerful stuff. For instance, the joint projects of Oksana Kazmina and Tolik Belov as part of Praktiki Tela, or the porn-horrors by Antigona. Although Antogona’s pieces are more often shown at feminist-porn festivals than at contemporary art exhibitions. In fact, the ‘wheres’ of representation matter very little to these artists; they can roll over from one to another ‒ art exhibition, scientific conference, porn festival. Whereas for contemporary art it is very important to be shown at certain specialised ‘contemporary art venues’.

I will go back to the thought the contemporary art as such is losing its monopoly on contemporality and generally its touch with contemporality; it is transforming into just another conservative type of activity, a culture craft (kulturniy promysel), to use Dmitri Prigov’s term. You have recipes and you manufacture some sort of matryoshka dolls following these recipes; at that, these matryoshka dolls can also be post-modern and even subversive.

It is predominantly men’s art?

Yes, the romantic model of the genius with an addition of play transgression, ability to juggle ideologically charged symbols. Artist super stars, pop prophets, showmen.

In the post-Soviet version, these are former Perestroika rebels, today ‒ highly respected commercial painters, Facebook public opinion leaders, influential cultural functionaries, nationalists or liberals.

Basically, these people have returned to their roots.

In that case, how would you define alternative art practices which are no longer linked together by institutions, by some sort of shared logic and narratives?

On the one hand, I think that it is simply art in the most universal sense, even the most traditional forms of painting or, for instance, symphonic music. On the other hand, it is the kind of art that is engaged in a dialogue with queer, feminist and leftist policies. Having said that, I, for one, do not understand the meaning of the term ‘leftist art’. Even when I myself say ‘leftist artists’, I mean simply artists, male and female, who happen to espouse that kind of views. I understand perfectly what leftist culture or rightist culture is, but speaking about art, that is exactly why it is called art: because it distances itself from any kind of officially approved practices. Art never allows itself to be caught by its tail; it always slips through your fingers, while engaging in a dialogue with politics on its own terms and whenever the fancy takes it.

When we say ‘leftist art’, we simply create yet another offshoot, another niche which will very soon become monetised and for which some pretty rigid boundaries will be set. What the defining of all these stylistic areas like ‘activist protest art’ actually does is localise pockets of fire, so that the flames would not spread.

Art is constantly playing with its own autonomy and can sacrifice it exactly to make the point of being in control completely. Artur Žmijewski called it instrumentalization of autonomy; at that, it is very important that it is instrumentalization of autonomy instead of art itself.

Acceleration or slowdown?

Sometimes acceleration is beneficial. For instance, when it breaks down ossified state and bureaucratic systems. And sometimes slowdown is beneficial. The work-to-rule action as a means of slowdown is the greatest invention ever. It is perhaps the best thing we can do today ‒ living in the mode of perpetual work-to-rule action.

And then there is the memory of trauma that holds us back, ties us to the past; it forces, makes us ‘stay with the history’. When we recall an injustice that has been committed to ‒ or by ‒ us, we cannot simply wave it aside and walk away. Responsibility to the past is hanging above our heads. All of the above things can be viewed as means of liberation: acceleration, slowdown, and working through a trauma. It depends on the way we use them.

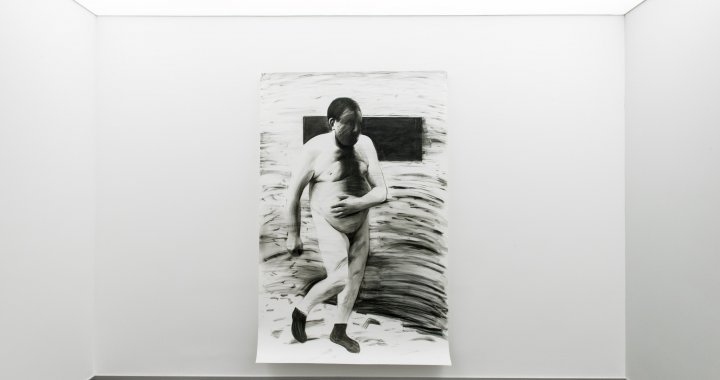

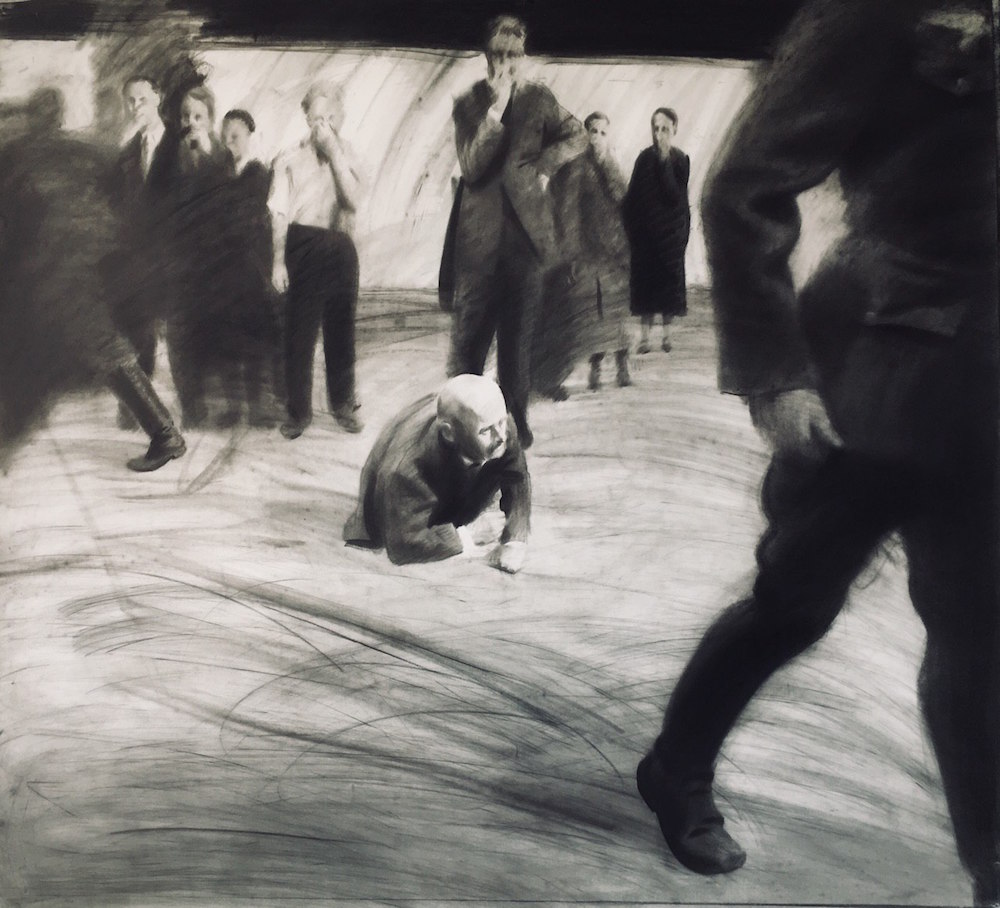

The Possessed Can Witness in the Court (2015) and The Spectators (2017). A view of the exhibition at M HKA, Antwerp

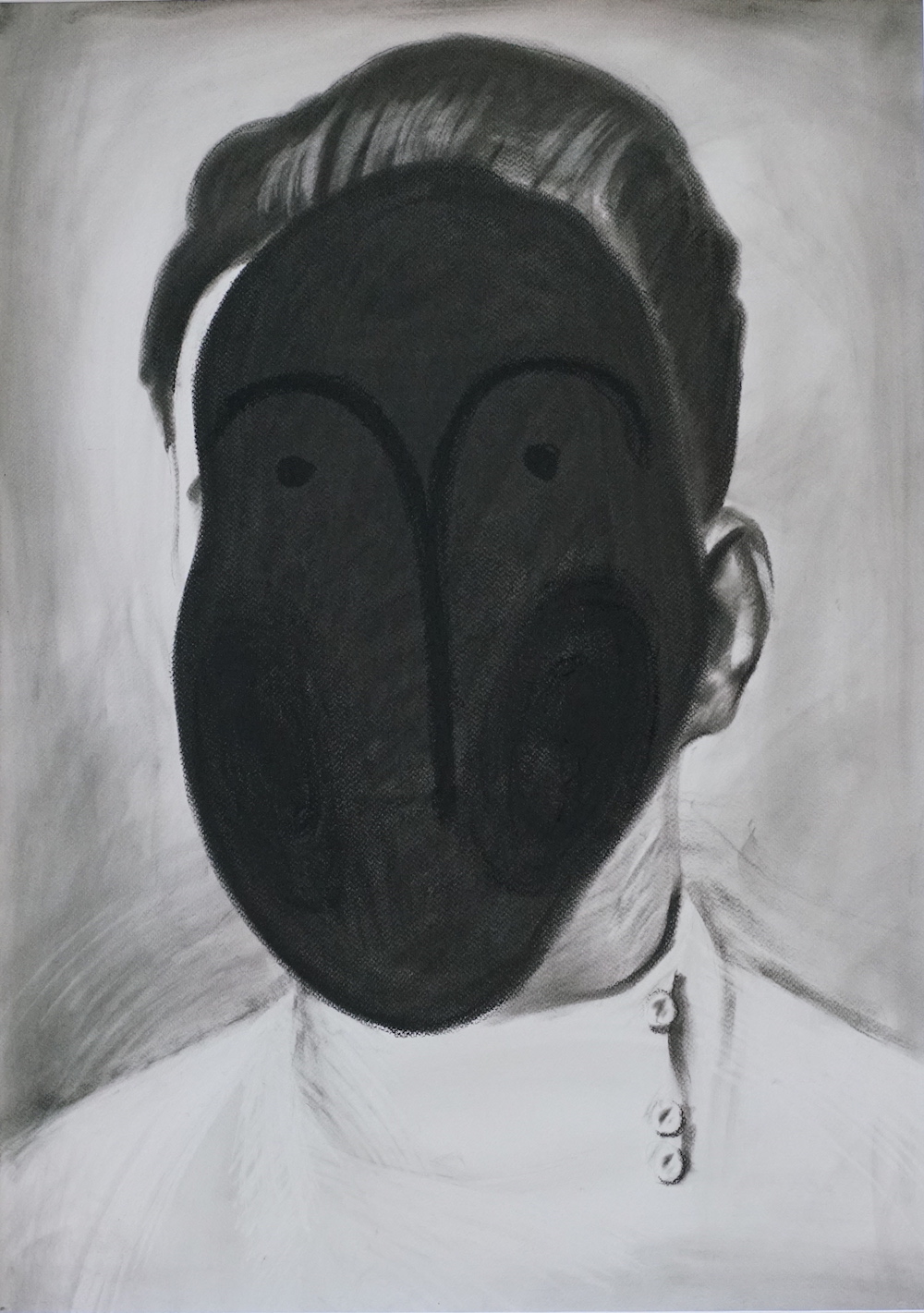

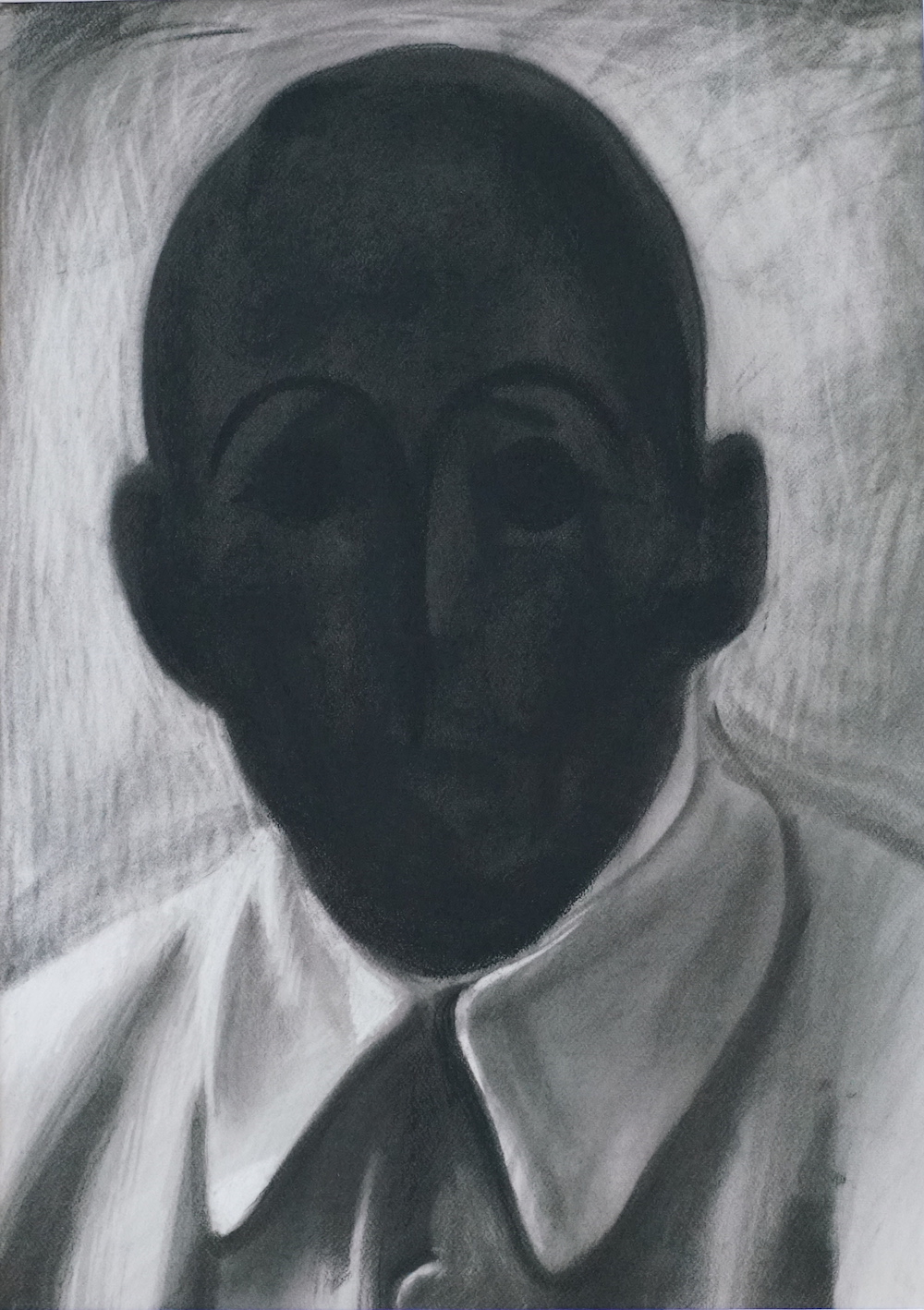

From the Spectators series. 2017. Paper/charcoal

That is an interesting subject ‒ regarding fixation with trauma. I think that trauma is not even so much staying stuck in the past as exactly the thing that drags us out from the time to the timelessness of its weird happening, claiming with its very structure: I cannot be overcome; I am the place you can never leave; a room that you cannot exit. While inside the trauma, we seem to be doomed to endless repetition, going back again and again to what constitutes the traumatic experience. Can you get out of a trauma through art? Or does it keep coming back to us as a painful experience?

As someone who has been diagnosed with a mental illness, I know only too well what it means to experience inevitably recurring affective states. You have to somehow deal with the reality of these states, use the intervals between them, predict their dynamics, their recurrence, work with it medicinally, therapeutically, etc. And that’s a responsibility. You know that if you relax, you will simply be swept away, smashed. On the other hand, you understand the limited amount of the resources, of your strength. All that makes you act strategically, as if you were on a battlefield. Plus, you also have become a person with a diagnosis (I find it an interesting description). A person whose symptoms, whose condition has been given a name, and not by himself or herself but by some sort of professionals, and who lives in this situation of quite coercive namedness. And the whole diversity of the affects is simplified here and fits the prefabricated models of what is called marginal or bipolar, or anxiety disorder, or schizophrenia, the latter being quite a dubious kind of diagnosis today.

So, yes, trauma does really hold us captive, makes us go around in circles, does not allow us to move along a straight line, leads us all the time to some sort of self-locking forms, ornaments. Yes, bet do we really want to move along a straight line? Is liberating movement really a linear movement forward? Perhaps slowdown, work-to-rule, also all kinds of diverse forms of traumatic entanglement have their own liberating potential. And perhaps we are destined to live our whole lives in the shadow of what would overtake us again and again ‒ but the problem is working out some kind of relationship with this state. Here the thing that is referred to as illness turns out to be a certain type of the Other you are living with.

On the other hand, when we speak about a historical trauma, experienced not by ourselves but by people who belong to different generations, the main ethical problem is the fact that you can utilise their pain to define yourself in today’s world, for instance, find motivation, forces or symbols for your political project. It is this self-same Benjamin’s spectacle of oppressed ancestors that provide more force for a revolutionary impulse today than any kind of image of a bright future. The art of the historiographic turn is based on personal tapping into collective traumatic experience.

Your series of works and exhibitions (Bones Mixed Together, Repetition of Forgetting, (Un)named) of recent years have been dedicated to policies of memory and related archive images from the 1930s‒1940s periods of mass violence in Ukraine and Poland. According to you, these images are still involved in the ‘memory wars’ of today. Interpreters from all sides use them, attributing to them different ideological meaning, whereas you deliberately mix them together, place them side by side, leaving a much more complex space for a view on the Volhynia tragedy, the Lviv pogroms and other events. On your comments for the Bones Mixed Together exhibition you said: ‘Looking at history directly, not through a lens of historical myth-making.’ What does it mean to you? Giving back the status of ‘naked life’ to the victims and using it as a point of departure for a new conversation?

Yes, we arrive at the indisputable factuality of a pit with human bones – bones devoid of any distinct national affiliation. More likely, what we are dealing with here is an ‘International of the Dead’. And yet this International is a form of existence for memory. That is an anti-nationalistic memory. It robs national projects of their foundation built out of sacralised victims of the past, a foundation that is necessary to carry on multiplying the ranks of the dead today. Victims of today are given this status of the naked life because victims of the past have been used to create sacred figures of a national myth. It is as if today’s victims are not worthy to be compared to the great victims of the past. The execution pit is nameless, but it will be given a name in the future, depending on the conjuncture of the moment; the victors will put up a memorial sign that will suit them best, appropriating the dead. Let the dead revolt against absolutely any form of ‘patriotic exploitation’ of their death.

(Un)named ‒ who are they? Nameless victims of the history, who cannot in any way be named, cannot be appropriated by any of the historical narratives and remain lost in labyrinths of guilt and memory? In what other way can we then speak about them?

It is those who have been robbed of their names, who have been given false names, identities and historical roles. And this is where we need to look for ways of restoring the names of these unnamed and clearing off the false names imposed on victims to propagandist ends. Among the atrocious photographs from the times of the Nazi occupation, images of hanged people wearing huge signs on their chests stand out. The signs say things like ‘partisans’, ‘saboteurs’ and other designations given by the executioners to their victims. The post-Soviet society seems to be debating to this day what would be the most convincing thing to write on these signs.

I brought with me Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others, and that was not a coincidence. Many of her ideas resonate with what you are doing in (Un)named. They deal with looking at pain through history, when we do not fully understand whose pain it is that we are regarding. Perhaps it is some kind of generic image of violence which, though time, endlessly affects and captivates? Or is it an attempt to liberate the image of a victim from various nets of ideological exploitation?

Perhaps it is not really about using images of past victims even for the cause of a social revolution at the same time as nationalists use them for the cause of a ‘national revolution’ and empire-supporters ‒ to consolidate the empire. And they may even be the exact same images. On the one hand, not naming, not denoting is the consequence of forgetting, of burying victims in oblivion, in some sort of secret burial places. On the other hand, it is the state to which we sometimes must go back, when a false name, a tool used by some present-day project, has completely obscured anything else.

Very often the documentary photographs featured in my works were used as quite randomly selected visual materials illustrating articles aimed at arousing hostility in Poles against both historical Ukrainian nationalism and the contemporary Ukraine that identifies itself with this nationalism. On the other hand, they could just as well be used as illustrations to articles aimed at arousing hostility in Ukrainians against both historical and contemporary Poland. In other cases, they allow mixing images from the times of the Russian Empire, the October Revolution, Stalin’s era and the post-Soviet years, to create a hybrid image of an eternally totalitarian Russia that is just changing its skin ‒ now putting on a monarchist one, now ‒ a Stalinist, now ‒ a Putinist one.

And weirdly enough, this hybrid image of Russia perfectly fits the constructs of Putin’s propaganda, which mixes these various images from the Russian history together inside the same vessel, only now it’s something most desirable, like a patriotic ideal. While this explosive mixture of Russian Orthodox monarchism and Stalinism can feature in texts by Ukrainian right-wing authors as a figure of evil, the whole thing, albeit with a sign of the opposite value, is also present in Putinist texts of ideological propaganda. And this is where an effect of mutual mirroring by the warring sides is created; these mutually reflected images cover anything they can. The propagandist constructions conceal the complexity of the real experience. The task of projects like (Un)named is, rather, liberating the experience ‒ making it very difficult to use images of victims in propaganda supporting any of the competing political projects.

Works from the (Un)named series, even when viewed through a computer screen, have a shocking impact… And this shock does not even seem to have an ideological basis; the images do not call for some kind of specific attitude. They leave you feeling confused…

These images are quite universal. But perhaps my main stake was on their obscurity. None of these photographs were intended to be ‘artistic’. This is quite a clinical documentation. And because it is record of events that exist outside the boundaries of mundaneness and are truly horrific, the picture creates a certain effect of unrecognition: we can hardly understand what is going on.

For instance, one of the works, where a thug is raising his arm with a club to hit a woman who, undressed and in black stockings, is being chased down the street. Firstly, the club in the thug’s hand is actually left outside the frame, and that is why it even seems unclear what he is actually doing. It may even seem as if he was greeting the woman. And then there are some kind of ropes in the foreground, right in front of the lens. It may be some kind of wires of cables behind which the operator has been standing. They create the effect of a torture chamber, although the scene is set in the street. And this woman: you can see that she walks with confidence, as if she was in control of the situation. It is an image that, thanks to a certain combination of coincidences and knowledge of their horrific content create an effect of a mystery, of an encounter with something you are actually not meant to witness at all.

From the Pogrom series (2016–2017). Paper/charcoal

Is it violence per se? Cultural violence?

Yes, violence per se. Moreover, it is a kind of violence that has not even been given a name as yet. Everything seems to be clear: it is an image of a pogrom, by far not the first Jewish pogrom in the 20th century. But here it is taking place in a relatively affluent Eastern European city where different ethnic and religious communities has been co-existing just fine for quite some time. This could have happened right here, at this very spot where we are sitting now, on this pavement. And it could have come as something nameless.

Later on, violence will be given various names; at that, these names will often be given to clear the way for still more violence.

What are these names that clear the way for new violence?

For instance, the duality of descriptions like ‘the Volhynia massacre’ and ‘the Volhynia tragedy’. Depending on which of these names you prefer, it becomes immediately clear whose side you are taking in the current memory wars.

There are practices of giving names that call for revenge, for new acts of violence ‒ not for punishment of the guilty but for revenge based on the principle of we versus them; at that, these ‘us’ and ‘them’ are nationally marked. And regardless of what kind of political project ‘they’ are currently choosing, it is always just a cover for their evil national nature, one that is hostile against our good national nature. ‘We’ are saying: if you were born a Ukrainian, it means that you were born on the side of the good. You have been historically very lucky. With the very act of your birth, you have already won a great moral victory.

At the beginning of our conversation, you referred to a trend of a global ‘historiographic turn’ that can be observed in Ukrainian contemporary art. Could you speak about it in greater detail?

There is a quite famous text by Dieter Roelstraete, After the Historiographic Turn, there is An Archival Impulse by Hal Foster. Paradoxically, it is through searching for ways of telling history, through critique of ways in which power is realised through ways of telling history, that contemporary art re-establishes its link with contemporality.

I will repeat myself: as I see it, contemporary art as a separate area of human activity has subjected itself to complete devaluation and has lost touch with contemporality. So what we really can talk about today are the ways in which art in the most universal sense of the word can engage in a dialogue with liberating political projects which actually are in touch with contemporality. A critical view of ways of telling history and subversive work with images exploited by political propaganda ‒ these are the ways of getting in touch with reality. And this subversive work can actually use the same transgressive techniques of ‘contemporary art’, except they would be taken from it as a trophy and returned to the status of an instrument, devoid of any intrinsic value.

And that is the same classical Benjaminian theme of history as we know it, as we study it, as we encounter it in academic sources, being the history of the victors. It is a history that is nationalist, male, militarist, clerical. It is a history backed by a collection of quite conservative values. And that is why the main attention should not be paid to events, because events in any case are largely in the hands of historians (even the most reactionary historian has considerably better access to facts than a progressive artist). The important thing is to study the ways of telling. We are interested in the actual mechanics of the narrative.

Broken Tree (2019) and Victory (2017). A view of the exhibition at MUMOK in Vienna

Who else of the young artists you find interesting are working with history, documentary methods and memory policies?

Yevgenia Belorusets, Nikolai Ridny, Nikolai Karabinovich, Lada Nakonechnaya, Yaroslav Futymsky. This is not even close to a complete list. The ‘historiographic’ trend in Ukrainian art is generally still waiting for an at least comparatively exhaustive representation and a systematised description.

Which philosophers of history have influenced you the most?

Benjamin is the most obvious name in this field; the name of Agamben is also close to being obvious. I also find very important Alain Badiou’s philosophy of event and the ideas of Jacques Rancière regarding politics and freedom of speech. I am currently reading a lot of Judith Butler. Butler very clearly shows how the problems of memory are rooted in practices of oppression and Not everybody will be mourned and remembered; behind every influential historical narrative there are always those who have been excluded and forgotten. Actually, ‘philosophy of history’ is something quite blurred, lacking a clear contour and overlapping with other areas of thought. What interests me, rather, is the whole diversity of approaches that philosophy, literature and art take to history, power and memory.

Do you see a difference between the ‘leftist’ and ‘liberal’ policies of memory?

We will never attain justice as long as the main subject of the policy of memory is the nation state. And at the same time, a simple aggregate of individual memories will never replace an agreement on ways of remembering something collectively. But is such an agreement that has not been imposed from ‘above’ even possible? Can there really be a ‘self-organisation’ of memories? I think that a ‘leftist policy of memory’ also depends on answers to these questions, not only on whether the Marxist optics inside the traditional museums and universities will be strong enough.

Shelter (2015). Concrete, metal, stuffed animals, glass, live plants. View of installation at the 14th Istanbul Biennial, the Istanbul Modern museum.

Could you tell at which point was it that queer theory and art that sustains a dialogue with queer theory became important to you?

Queerness is an integral part of liberating or freedom-practicing thought. If you consistently practice political liberation, you inevitably end up as a feminist or a post-feminist; you inevitably cultivate within yourself queer sensibility, intersectional optics, and at the same time you also inevitably recognise the economic dimension of all the problems that policies of identity are targeting, or so it would seem. And this is where, at some stage, you either artificially limit your own vision to a specific area: ‘I am a leftist focusing on class struggle’ or ‘I’m a feminist fighting exclusively for women’s rights in the context of the current economic and political project’ (I am referring to liberal feminism) ‒ or you see the connectivity between all these things. In the latter case, everything comes together: problems of identitary and universally economic level, queerness and the ‘historiographic turn’. These are all parts of the same machinery.

Another question relating to the same area is whether you should take into account your own mental and psychiatric problems if you happen to be concerned with completely different things in your art practice? I recognise that they objectively do influence my reasoning, my sensibilities. But the matter remains open for me ‒ should I allow it to enter the boundaries of my artistic practice or should I perhaps leave it as part of my personal problems, which sometimes may somewhat hinder me or become a disadvantage but are nevertheless essentially a technical issue.

How is such an art possible today that works with the identitary, while avoiding policies of identity where identity becomes a rigid ideologeme (as is the case with many policies of national identity)?

It would seem that there are many answers to that: combining reflection with experience and speaking in the name of the groups to which you actually belong, retranslating your actual experience.

However, when it comes to historiographic problems, things get more complex. Because this is where we deal with trauma experienced by others, with catastrophes which we haven’t witnessed in our lifetime. And this is where the image of the ‘common horizon’ emerges. The Holocaust is such a horizon that serves as a point of reference in relation to which we define ourselves, all of us. The same way we define ourselves in relation to the Gulag. Our relation to the Gulag defines what we are today.

This self-defining through agreement or refusal to recognise the sacrifice of the national heroes of the countries in which we live. Any nationalist mythology is built around the fact that we refuse to recognise certain sacrifices. Or construct something like a hierarchy of sacrifice: ‘our dead are better than yours’. Who we are and who we are with depends on which version we choose – ‘the Volhynia tragedy’ or ‘the Volhynia massacre’. And this is where we once again find ourselves in the position of carriers of experience, except this is the experience of today’s wars for this kind of historical optics or another, this way of remembering things or another.

History is a battlefield. Each of the photographs I use in my works is an actual battlefield. And that is why these works are not the same as ‘historical art’ in the traditional sense of the term, the aesthetic equivalent of the selfsame historicism discussed by Benjamin as opposed to historical materialism. The thing is ‒ these battles are the problems we are dealing with today. And I invite the viewers of these works to define themselves not so much in relation to what happened here in the summer of 1941 but to the polemics and conflicts that have to do with interpretations of these events. (Un)named is a political work that deals with the subject of contemporary life, even if it looks like something slightly different. But that is the answer I give through my own artistic practice. As for some sort of generalised universal methods of working with the identitary ‒ perhaps there aren’t any.

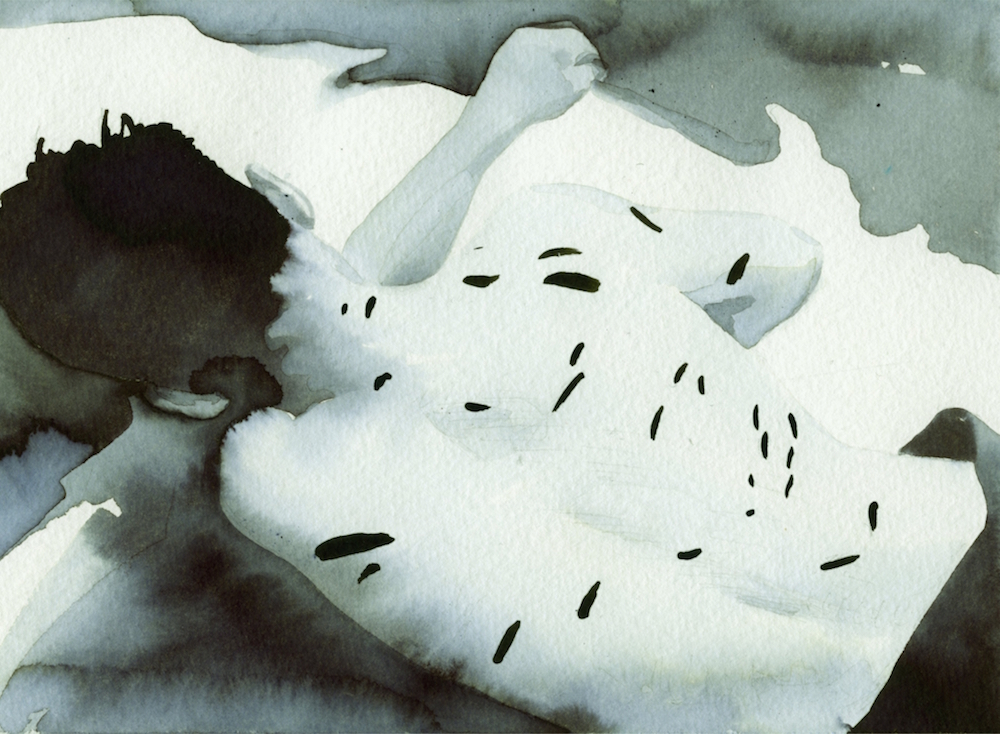

From the "Chronicle" series (2015). Paper/ink

What are the projects you have planned for the foreseeable future?

With curator Jessica Zychowicz, we are currently working on a project that deals with the legacy and fate of Bruno Schulz. For a version of the (Un)named exhibition at the Odessa Museum of Contemporary Art, Jessica wrote a text and also held a talk on masochist optics in the art of Bruno Schulz and my works which are part of the project. Schulz’s works (are you familiar with The Book of Idolatry?) are weirdly similar to some of the photographs from the Lviv pogroms. In both cases we see naked or half-naked women in the streets; furthermore, these are often undressed women wearing nothing but black stockings. And next to them ‒ some sort of expressly monstrous-looking men. Except, while the men in the pogrom photos are pulling faces, having fun and showing in every way that they are the masters of the situation, it is the other way around in Schulz’s pictures ‒ they are humiliating themselves and clowning around to entertain these dominating women. But it is also submerged in the general atmosphere with its fantastic lighting, with masses of darkness and patches of light, the distribution of which is completely dependent on the will of the artist. These are scenes in which Schulz, to some extent, influenced by Goya, renounces realistic lighting to create his own masochistic theatre. I make replicas of the Lviv pogrom photos and replicas of Schulz’s works in such a way as to invoke a coherent visual register, so that these images could almost be mistaken for each other.

The exhibition will also feature an installation dedicated to Schulz’s life in Drohobych, his survival during the years of the Soviet regime and death during the German occupation. The thing is, during his ‘classical period’ in Drohobych, Schulz paid no attention whatsoever to any kind of Ukrainian presence in the city. During the Soviet years, however, he started to draw people in Ukrainian traditional dress (or, rather, in folkloric, pseudo-national costumes); at that, these people tend to carry Stalin’s portraits. And that is how Ukraine suddenly appears ‒ compulsorily ‒ in Schulz’s work. There is also apocrypha on a painting dealing with the annexation of West Ukraine to the Soviet Union, in which Schulz actively used yellow and blue, for which he was arrested and interrogated. And there is also an illustration published in a Soviet Drohobych newspaper: a ‘folkloric’ Ukrainian lady at a Soviet demonstration turns out to be a costume-wearing character from The Book of Idolatry: the same facial expression, the same posture. But this is all playing games with himself by a man who is fighting for survival. He painted his final murals at the house of the SS officer Landau and was shot to death on the pavement, right next to the fence of the park that now carries the name of [Stepan] Bandera. And near the park fence, approximately at ankle height, there is a memorial plaque for Schulz. And it is this historical and political ornament, linking Schulz’s biography and his desperate attempts to break free, escape either to a masochistic phantasm or mythologised childhood memories, that is to become the subject of the work. Schulz and Ukraine; Schulz and masochism; Schulz and ‘mythologization of reality’; Schulz and the Soviet regime; Schultz and the Holocaust; Schultz and the image of an endless and hopeless province, where ‘the world is what it is, and there are no other worlds for you except this one’ (Bruno Schultz, Springtime); Schulz and the ghostly image of the external world ‒ out of all these things we are trying to build a cohesive story.