“The World Has Been Seeped in War”

Ukrainian artist Nikita Kadan on the changing reality, and the ways it’s perceived and reflected on half a year after February 24th.

Another one of our publications with Nikita Kadan, one of the most internationally recognized faces in Ukrainian contemporary art, went up in the first weeks of March. Then, the Russian aggression was threatening Ukraine’s very capital, with Kyiv’s outskirts overtaken by enemy tank columns. Half a year has passed since then. Kyiv is no longer under direct threat, but war is still raging in the country’s East and South. How does art life persist in these conditions? What sentiments can be felt in society and in the art community? How is the new reality, where safety ceased to be certain and danger became both constant and unpredictable, being reflected upon?

Half a year later we’ve reached out to Nikita again to discuss these questions and the PinchukArtCentre’s recent opening, the large-scale international project “When faith moves mountains”. Like before, Nikita talked deliberately, taking his time, thoroughly reflecting on the reality that many of us couldn’t imagine even a year ago. “Reflection is not at all a trivial task”, – he says.

Nikita Kadan. Movable Circle. 2022, Iași, România

Nikita Kadan. Movable Circle. 2022, Iași, România

Where are you currently?

I’m at a residence in Uzhgorod. It’s called “Вибачте, номерів немає” (“Sorry, all rooms are taken”), the location is a post-soviet hotel “Zakarpattia”. It’s being managed by the artist Petro Ryaska, for six years already, I think.

But you also visit Kyiv?

Yes, I was there just two days ago.

“When faith moves mountains” / Exhibition view at the PinchukArtCentre. Photo: Сергій Іллін

How is art life going there? What kind of exhibitions, or other projects, are taking place?

Exhibitions still do happen, although obviously in a manner completely different from what it used to be. The one I was visiting Kyiv for was also the one I participated in – the “When faith moves mountains” exhibition in PinchukArtCentre, named after the piece by Francis Alys. It was brought to Kyiv by the Antwerpen M HKA museum. They put many works from their collection to be exhibited alongside a selection of pieces from Ukrainian artists. It’s a precedent in its own way – a museum brings an exhibition to a city under shelling, an exhibition that features internationally famous artists like Barbara Kruger, orlan, Luc Tuymans or, again, Francis Alys. I know there are also other locations in Kyiv with a couple smaller shows.

Nikita Kadan’s work at “На часі” (On Time) Festival in Nizhneyurkovskaya space

Have you seen any of those?

I had a cursory glance at the exposition of the war-time works in The Naked Room, mostly on paper, but unfortunately I haven’t seen the photo exhibition in the I Gallery. There’s also this micro-festival called “На часi” (On Time), it takes place at an art space on Nizhneyurkovskaya – a former weaving factory building that houses several clubs along with some sites for electronic music and DIY-culture related projects. An important spot on a young person’s map of Kyiv. It has it all from electronic music performances to selling merch to contemporary art. Pieces, including one of my own, are exhibited in different spaces inside the factory. During the festival the place is crowded – people have undoubtedly been starved for active socialisation.

All of it, obviously, focuses on the war-time realities to some extent. “На часi” (On Time) is more about the life-goes-on-despite-all aspect, while the PinchukArtCentre exhibition is something very thematically condensed, although not as illustrative. The one straightforward journalistic piece there is the exhibition of Russian war crimes documentation. There’s a video by Lyosha Say composed of hundreds, if not thousands of reportage photos depicting the damage from Russian air strikes. But this is more of an intervention, the main exhibition involves quite multilayered and often unobvious pieces.

What is your piece there?

A work from The Shadow on the Ground series, I started working on during the first month of the invasion. A black plowed field and dark human silhouette which becomes barely distinguishable on the field.

When we talked back in March, you were already working on it…

Yes, but it turned into a series of images, and the last of them is currently exhibited in Kyiv.

Nikita Kadan. The Sun. 2022

Did you have a chance to talk to your fellow artists in Kyiv?

Yeah, I met with many of them... Including those who escaped to the West and started coming back for shorter or longer periods. I met the artists participating in When faith moves mountains, and also those we went to the ruined towns around Kyiv together: to Bucha, Irpen, Hostomel, Borodyanka.

Also, in the past three weeks I’ve taken what is, in my opinion, a very important personal step, although I still can’t quite grasp where it might lead – I’ve rented a flat in Bucha. I want to turn it into an atelier, both for myself, and for some visiting artists. I wouldn’t call that a residence, I doubt I can make any sort of open-call there, and it will probably remain very low-scale, but I do want to invite artists to work there from time to time. The working name of this whole thing is The Centre for Coming Back to Life Studies. I’m interested in how places return to life after horrific collective trauma. There’s a lot of forms and strategies you can employ, from some kind of grass-roots youth socialisation to horticulture projects to simply repairing partially destroyed buildings. I’m just starting to look in this direction, and there might be some sudden turns, some things I can’t account for. When I get back to Kyiv, I plan to spend some time there, in that flat.

A photo taken in Gostomel, Nikita Kadan’s Instagram

It was not your first visit to Bucha, was it?

After the 24th I went there twice, but each time only for a short while.

Is Bucha changing, or returning to life as you say?

Yes, there’s a lot of activity in Bucha – everyone is trying to get things back to normal, putting up new doors and windows, repairing some houses and knocking down what’s ruined beyond repair. Unlike the neighbouring Hostomel and Borodyanka, Bucha is coming back to life in full force.

What do you mean by “unlike”?

I’ve been to all of these towns. Borodyanka is just a ruin. You can spot some passers by in the wreckage, but the town is close to dead. Hostomel was hit hard by the air strikes. People from destroyed houses spend their days in the courtyard, and when it’s raining and during the night everyone goes back to whatever apartments still have a ceiling. All the windows got blown out, of course. People are ready to move, they’re just waiting for the government to help with housing.

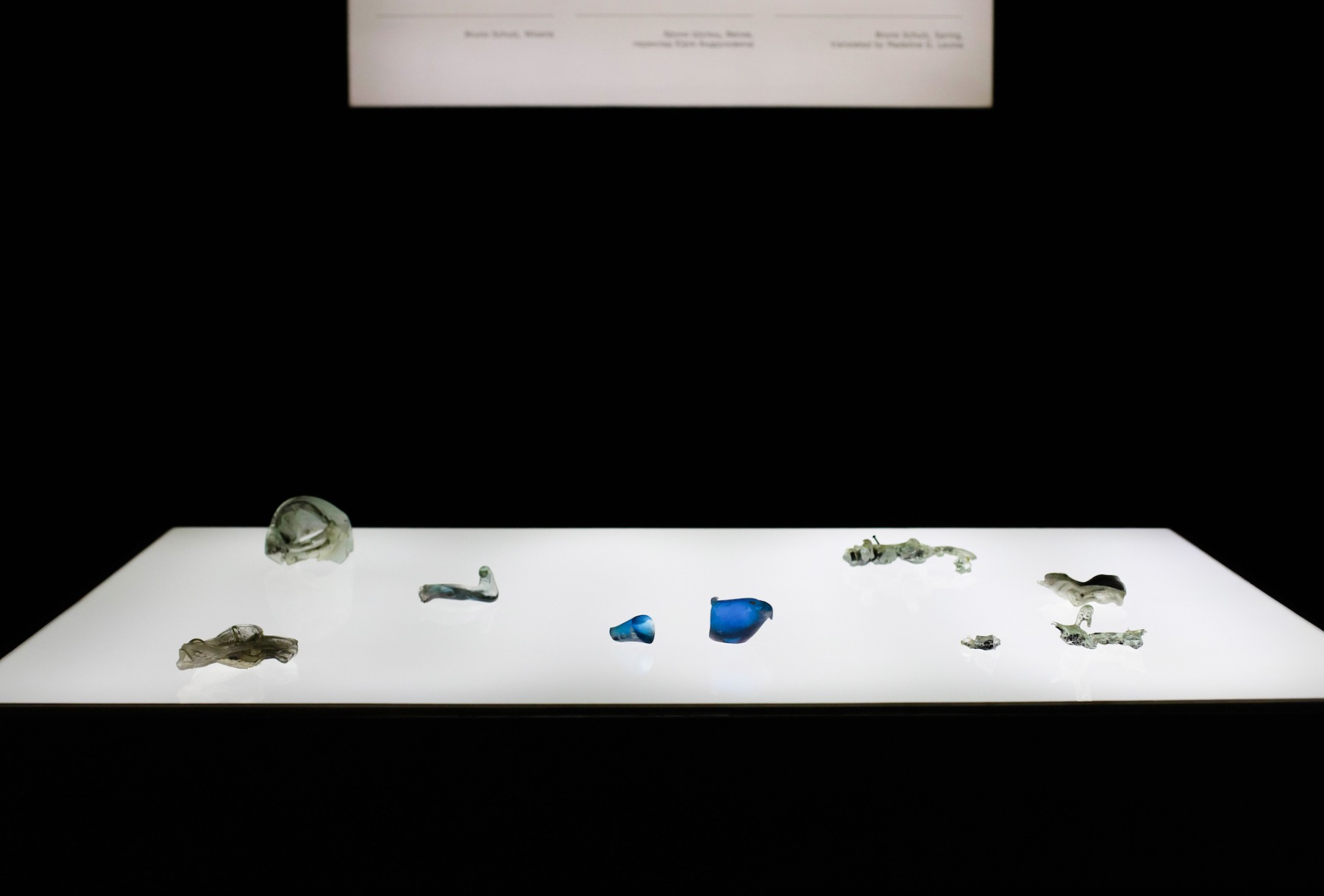

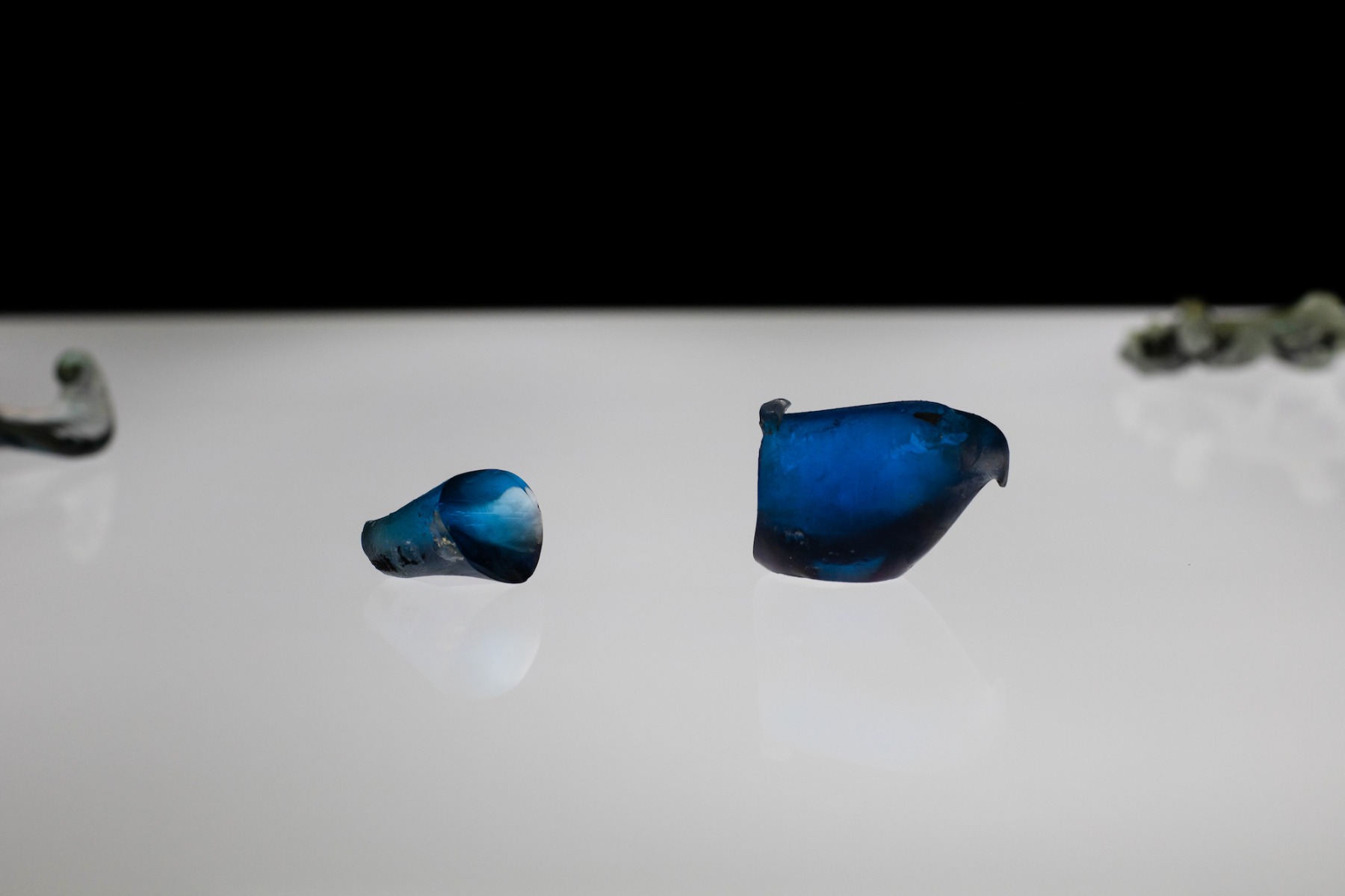

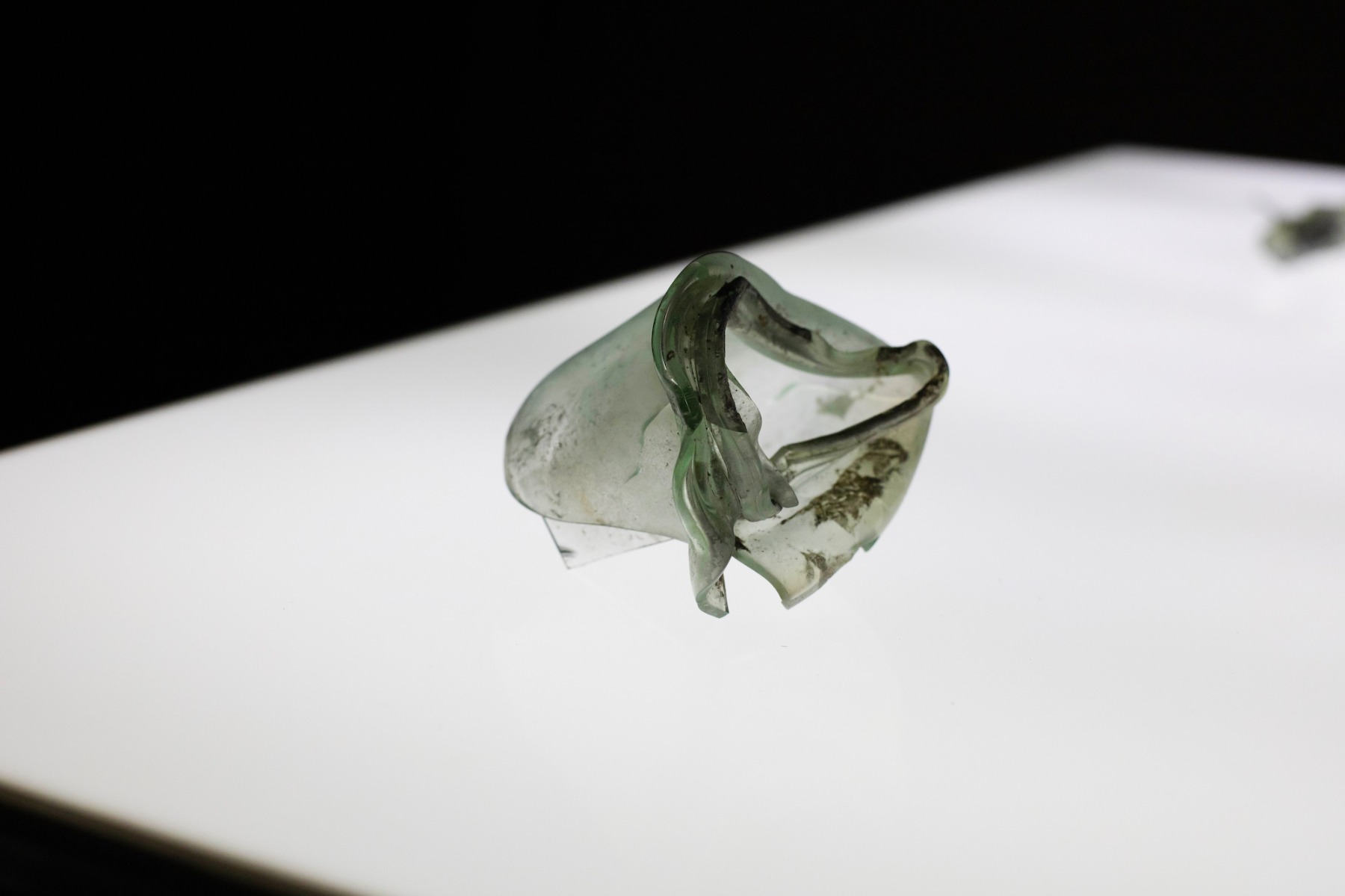

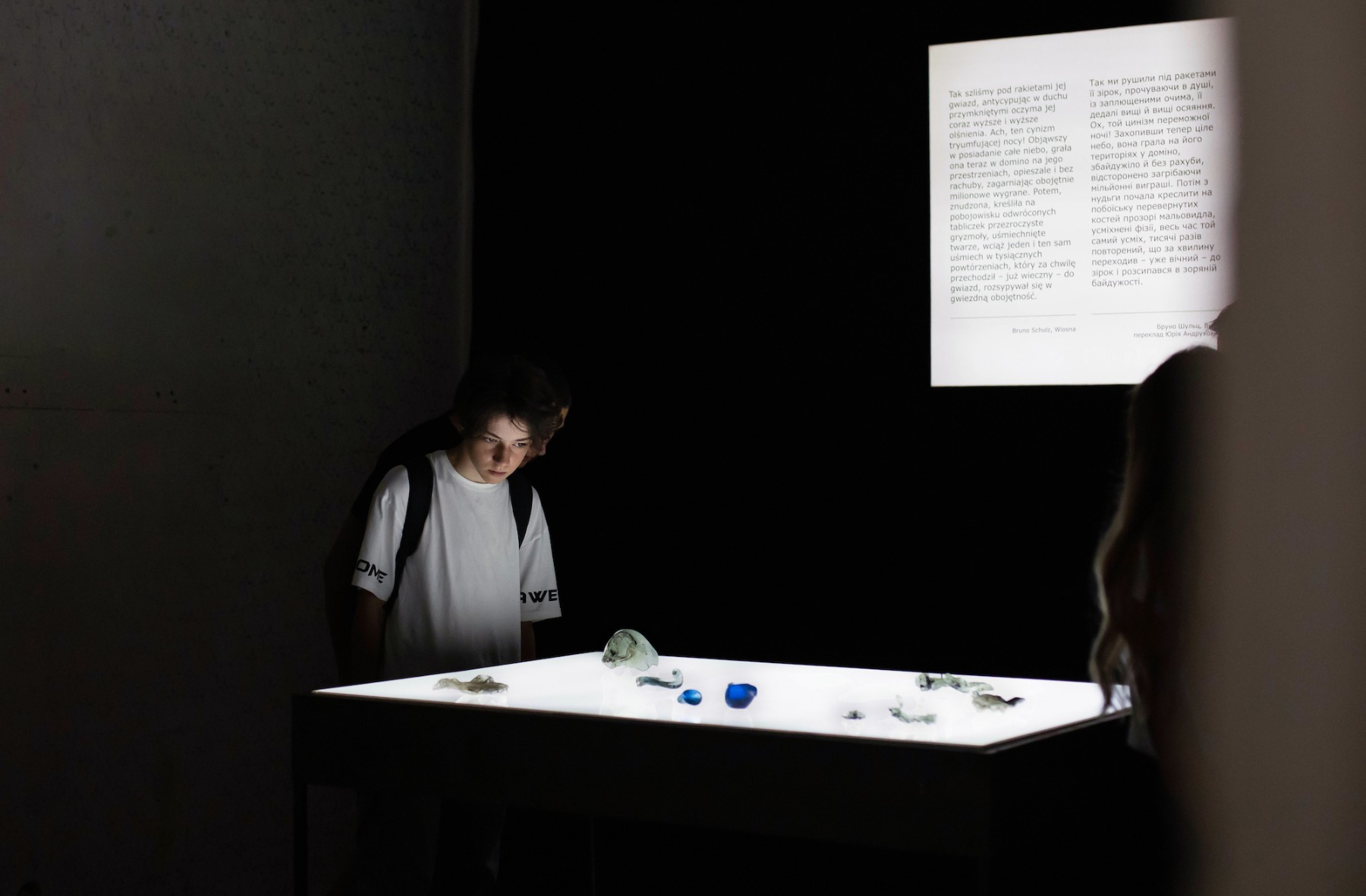

Nikita Kadan. 'Stars of the Province', 2022, installation in the room of Bruno Schulz, Drohobych. Materials: melted glass items from the ruins of Hostomel, iron, lightbox. Text - the quote from 'Spring' by Bruno Schulz. Produced for Bruno Schulz festival in Drohobych with the support of 'Insha Osvita', Ivano-Frankivsk

I asked you if you had the chance to talk to other artists in Kyiv... It’s clear now that the war drags on, that any long-term planning of an artistic career is basically impossible. How do artists respond to that? What have you heard in conversations or have been told personally?

You know, even if in the outer world time seems to drag on in regards to what’s happening in Ukraine, here, despite all the exhaustion and burn-out, time still moves at a rapid, passionate pace. This rush of adrenaline is still at work in some form – if not for all, then definitely for many. Of course any professional prospects in Ukraine are becoming problematic and murky, while the question of survival has grown more acute. However, even before the 24th that question was already quite pressing. Even before the war there were no private markets or systems of public finance which would have supported our lives and work, so we were already somewhat prepared.

Talking about support from the international art-community... Is there something that should’ve been done, but hasn’t yet?

That’s a good question... Material support for those who stayed in the country is a key issue, a question of survival. However, since I’m not a refugee, my view may be limited to that perspective. As for whether the art itself has enough visibility, I think the community should turn away from gestures of political support to Ukraine (even in the shape of exhibitions) in favour of deeper forms of reflection on what is actually happening here. It’s understandable that people had to react as soon as possible, but that kind of response has its own implications – these are surface-level reactions. This all might come to a check-list situation – we made a Ukrainian project in 2022, done. And I don’t know if there’s an international institution working on any deeper projects that involve actual research and analysis, projects planned at least a year in advance if not more. If something like this did exist, it would go public under conditions we can’t yet imagine. And it would be dedicated to understanding Ukraine, instead of just seeing it and recognizing the fact of its existence – an attempt at analysing the logic behind the processes that brought us where we are now.

Nikita Kadan. 'Stars of the Province', 2022, installation in the room of Bruno Schulz, Drohobych. Materials: melted glass items from the ruins of Hostomel, iron, lightbox. Text - the quote from 'Spring' by Bruno Schulz. Produced for Bruno Schulz festival in Drohobych with the support of 'Insha Osvita', Ivano-Frankivsk

Has anything changed since our last conversation, is there something new in the air, in the public sentiment, that you think is important?

What is happening no longer seems fantastical. Everything has become rooted in reality. It’s already hard to remember how the world used to be. The very air tastes and feels differently, and it’s difficult to recall the very senses that constituted the previous world. So yes, we are getting used to the war, but, I must repeat, the passion has not gone away. This isn’t the kind of “getting used to” synonymous with giving up and refusing to take initiative, instead it’s an absolute acceptance of the reality unfolding before us. I used to wonder at already fully conscious people who came of age in the post-2014 reality – with an annexed Crimea and an occupied Donbass. Perhaps there will be a generation, whose only reality growing up would be full-scale war, which, as we’ve learned already, can really go on forever. It can fade, it can pause, it can take breaks, and then a new offensive action, new escalation can happen. Finally, it’s no longer an axiom that wars must end at all. This seemed to be a given, but we had to put that assertion under doubt as well. The world has been seeped in war. The sensibilities are being restructured, the thought is being restructured, and art too, is being restructured. The form of the art institution and of different ways to keep art alive and capable will also change significantly.

Nikita Kadan. 'Stars of the Province', 2022, installation in the room of Bruno Schulz, Drohobych. Materials: melted glass items from the ruins of Hostomel, iron, lightbox. Text - the quote from 'Spring' by Bruno Schulz. Produced for Bruno Schulz festival in Drohobych with the support of 'Insha Osvita', Ivano-Frankivsk

In what way?

There definitely will be more than one way… On one hand, I think, there will be a propagandist line with a high degree of uniformity in both thought and affect, but as a trade-off it will suffer from self-censorship and blind spots of expression. But it won’t be the only way, and judging from the first few years of war, it won’t even be dominant. If art stopped speaking from itself, from the point of endlessly searching for its own difference, and started representing and promoting national unity back in 2014, we wouldn’t be the democratic Ukraine we are now. We are fundamentally different from the enemy side, because among other things we’ve retained the capacity for internal critique and the right to doubt ourselves. So I think there also will be a non-doctrinal, anti-ideological cultural line, but partaking in it will come with much higher stakes than before. We may expect an aggressive reaction to any discourse that goes beyond the patriotic canon. However that canon itself is in the making, and we can influence it, there’s a lot of unresolved questions within it.

After all, wartime art relies, first and foremost, on experience that is quite specific and unprecedented. This experience can be both collective and individual. The canon for describing collective experience is usually formed over a long stretch of time, while individual experiences speak through the unprecedented, through the un-existence of proper words and proper images. It has a certain tongue-tied awkwardness. There’s also the option to rely on the bare naked givens – it is what it is, interpretations will come later.

I also think there will be a lot more personal, completely private practices, conducted by people for their own sake. However, it’s up to debate whether their possibilities are compatible with the conditions of surviving during both late-stage capitalism and active warfare. We’re wedged by economic precarity on one side and bomb flying towards your house on the other, so any non-practical activities might prove unbearable for many, but I still feel there will be a certain place for them.

Nikita Kadan. 'Stars of the Province', 2022, installation in the room of Bruno Schulz, Drohobych. Materials: melted glass items from the ruins of Hostomel, iron, lightbox. Text - the quote from 'Spring' by Bruno Schulz. Produced for Bruno Schulz festival in Drohobych with the support of 'Insha Osvita', Ivano-Frankivsk

This art for its own sake is something created for the time after the war?

Perhaps. If we still believe, there will be time after the war. To be honest, I’m preparing for war to always exist nearby in some shape or form – maybe as frozen conflicts, maybe as something smouldering, but ready to be reignited. And I’m preparing for it to constantly affect everything else. Maybe the point is not to expel the war from existence altogether, but to retain areas of life free from the war.

Nikita Kadan. We are the Price. 2022

Including some kind of artistic areas?

Them too. After all, art is connected to radical political imagination, unashamed of prophecies. However, those kinds of political visions are only possible when you can “forgo the body”, which is impossible during the war.

You know, in this part of the world the radical anti-war politics seemed naive before 2014, and impossible after 2014. Most of us simply didn’t believe in war, couldn’t imagine it as part of reality. Previous Russian invasions didn’t face the kind of solidarity in resistance we see now. Neither the post-soviet countries, nor the West have taken them seriously enough. Even after the first shock of 2014, at the time when the war had lurched through the hot phase into a frozen conflict, many people simply waved it away and nearly forgot it existed. But it was right there all the time, even if it seemed hardly noticeable – for everyone who didn’t live in eastern Ukraine or Crimea, of course. Now it has touched everyone. And there’s no longer a part of life it hasn’t permeated in some form. But the fact that many people even here in Ukraine talk about the period before the 24th as the time ‘before war’ is plain evidence of just how much comfort we find in even a partial self-inflicted blindness.

Have you reconsidered your mission as an artist under today’s conditions, or has your stance remained more or less the same?

My stance has remained firm. For me the war began in spring of 2014, and since then I abide by the same criteria. I talk about that war in the same terms. And most of all, in my work I continue to draw the same lines I started back in 2014. Of course I continue developing those thoughts, not just repeating or altering them. At the start of these events my priority was to somehow instantly museumify the war, to immediately make history of a burning now, but today I’m concerned with the poetry of material proof, of history’s verdict being written and proclaimed in the here and now and postponed to some distant future. Anyway, the break that changed the character of my world happened in 2014. What’s happening now is just its natural development.

Nikita Kadan. Photo: Klaus Pichler, courtesy mumok

Do you think an artist in these circumstances is someone who documents the war, reflects on its experience, or otherwise – someone who thinks about what can extract or distract people from the experience of war and, at least for a time, steer their consciousness towards something different?

As we know, there is no universal artist figure. Everyone involved in art does different things. I accept all kinds of strategies: from recording and documenting the immediate experience, to reflection, to, as you’ve said, distraction, to agitation and propaganda. The field of art contains everything. But I think that under the current conditions reflection is the hardest one. It’s critical thought that faces what seems to be the most unbreachable obstacles and barriers.

A free-flowing reflection on the current moment is something just borderlines socially acceptable. During wartime people choose their words more carefully, they’re restricted in their thinking. There can be different reasons for that, be it personal responsibility or fear of judgement. But the fact remains that a publicly articulated thought becomes slower and more unwieldy. If we’re talking about an actual thought of course, and not just chirping that everyone instantly agrees with.

Slower and more careful…

Yes. However there’s carefulness that arises from the pressures of public opinion, which is something that has always put art to the test of its difference and independence. That test certainly became harder now, but it was always there. And there’s also carefulness as a way of navigating the mine-field of meanings. Here you are accountable not to the civic consensus, but to the actual and true state of things.

Sometimes it helps you to go deeper. You lose the mobility on the surface of events, but from the point where you’ve stopped and rooted yourself... you can start digging.

Title image: from the project of Nikita Kadan "Stars of the province", Drogobych, 2022