Mykola Ridnyi and registers of reality

A conversation with an artist from Ukraine participating in the 13th Survival Kit contemporary art festival

There is a building in the Old Town of Riga where if you go upstairs to the second floor, you will find a room where a video is being projected on the wall. There is a huge cushion on which you can sit down, and a set of headphones. As soon as you put them on, you will find yourself in the Kharkiv of 2017 ‒ a large post-Soviet city with streets, gateways, buildings, and people living in these buildings. It is a film entitled ‘No! No! No!’ by Ukrainian artist and director Mykola Ridnyi – part of the programme of the 13th Survival Kit festival of contemporary art running in Riga through 16 October 2022 in the former bank building right next to Dome Square.

Mykola came to Riga for the festival, which is not a simple thing to arrange: as we all know, Ukrainian men of his age are only allowed to leave the country with special permission; sometimes it’s about representing their country at a cultural event, but sometimes it is more like the mission of the poet and writer Andriy Lyubka, whom I met at another festival: he is raising money to buy jeeps and pickups and then drives them to Ukraine to hand over to the Ukrainian army. But Mykola was here for the festival opening, and a few days later we met for this conversation at the Alberta Street office of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, which had invited him to Riga.

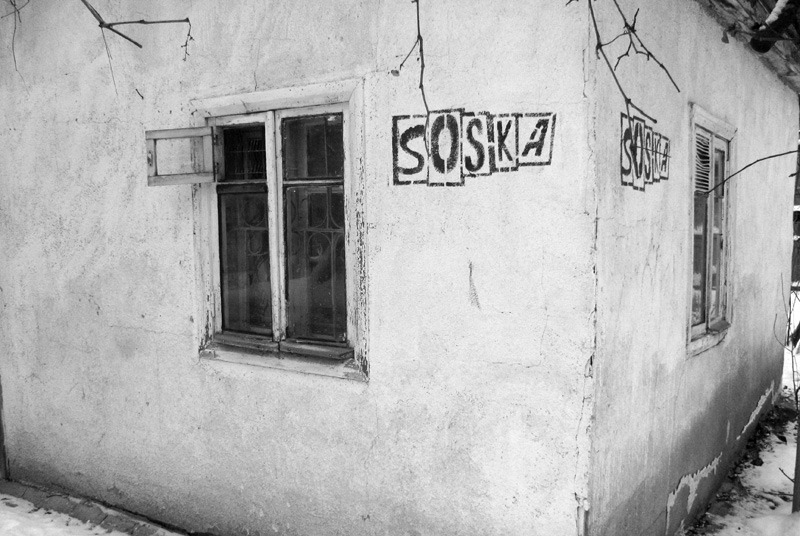

Mykola was born in Kharkiv; the city holds a significant place in his life. Its name has also been frequently mentioned since the beginning of the Russian invasion in Ukraine: the defenders of the country managed to hold on to the city, recently also liberating the occupied territories of Kharkiv Oblast. At least the shelling of the city has finally stopped now. It is here that Mykola studied art and became a member of the SOSka art collective and co-founder of the cult art space of the same name in one of Kharkiv’s abandoned buildings.

‘An artist who gives simple answers to complex questions is a bad artist,’ Mykola Ridnyi said in a 2019 interview for the Ukrainian magazine ‘Bird in Flight’. ‘I am interested in the factor of time in art. I view art not as entertainment but rather as a certain mental activity, an intellectual effort that the viewer must make on a visit to an exhibition. [...] There is a certain continuity in time to a film: if you don’t watch it from beginning to end, you may not understand a thing.’

Yes, it is definitely not a momentary flash-like visual impression; rather, it is a process. To make sense of how it works, what the most important things about it are, and what the context is to Mykola’s work (not just films but also sculptures, installations, objects), we had quite a lengthy and circuitous conversation. I hope the reader of this conversation will not mind the time it will take ‒ because we discussed, among other things, events that have been, and still are, shaping not just the future of Ukraine but also the future we will all be living in.

Mykola Ridnyi at the opening of the 13th Survival Kit festival of contemporary art. Photo: Kristīne Madjāre

I would like to open our conversation with Kharkiv. The city where you were born and raised and where you, at some point, started doing things that you found interesting. That includes the SOSka independent art space, a venue of huge significance for the city. Could you tell us about this time?

SOSka Gallery opened in 2005 and existed for seven years. It was launched simultaneously with the art group of the same name, created by me and my comrades. These two things went hand in hand ‒ the space and the art collective.

How did this initiative come about?

We were students at the time, and we painfully felt the conservative approach to art education in Kharkiv. The same could be said not just about Kharkiv but also the rest of Ukraine, or even the whole post-Soviet space. You had to work your way through the conventional syllabus; you were not taught art ‒ you were taught a craft. There was nothing like thought exercises or experiments; moreover, that kind of thing was seen as a distraction from your studies. Whereas what we felt we needed was a kind of laboratory where enthusiasts of experimental art would come together to debate, exchange ideas and, through this, further the whole process.

Essentially, it was no more than a squat at the time, an abandoned building which we commandeered; later the owners appeared. And we reached an agreement with them ‒ we paid a small rent while keeping an eye on the space. We had non-stop art shows, musical events, talks and screenings...

SOSka Gallery

What was the Kharkiv of the time like for you, in general?

Kharkiv really changed when the war started, that is, in 2014. Its role inside the country changed, its geopolitical position. If Lviv was the main gateway to the west, to Poland, Kharkiv was the same on the route from Crimea and Donetsk to Russia in the east. There was, of course, the 2004 Maidan, the Orange Revolution. But I would not say that it changed the city in any significant way. There was not a hint of anything like the so-called ‘Leninfall’, the demolition of monuments to Lenin linked with decommunization, at the time. I remember gigs by the popular Ukrainian bands Okean Elzy and Vopli Vidopliassova; they came to the city and performed on the main square in support of the Orange Movement ‒ with a monument to Lenin in the background. Orange banners, signs with the name ‘Yushchenko’ ‒ and the figure of Lenin behind all that.

On the whole, I remember the city being quite apolitical in terms of relations between Ukraine and Russia. There was some public dissent, but it had more to do with social issues: people were frustrated with not getting paid, or with all kinds of other mundane economic problems. From time to time there were protests, like a strike of public electric transport employees. It is also important to note that sometime around the mid-2000s, power in the city was grabbed by a certain clan, by shady characters like Kernes and Dobkin with criminal pasts. They were antidemocratic leaders with absolutely no interest in the public’s opinion; they imposed their own views on the city, taking care of their personal interests and profit.

Still from the film ‘Regular Places’ (2014–2015)

You said everything changed in 2014…

Yes.

How did that happen?

First, the city used to be perceived as a certain peaceful space. In early 2014, when there was an attempt of a ‘Russian Spring’ in Ukraine and Kharkiv became a link in the chain Donetsk‒Luhansk‒Kharkiv as part of the ‘New Russia’ project, the tension spilled out into mass confrontation in the streets. The oblast administration building changed hands several times. First it was under the control of the Maidan activists; incidentally, they did not have to capture it: when Maidan triumphed in Kyiv, the Kharkiv administration simply fled the city to observe further developments from a safe distance. And people simply took it over; there was no clashing with security. Then the pro-Russian crowd stormed the building to ‘drive out the fascists’, as they saw it. This escalated into violent clashes and fighting. At first, the pro-Russian crowd significantly outnumbered the Ukrainian activists. And 1 March 2014 was an excellent example of their ways of humiliating and mocking the people they had evicted from the building: they forced them to crawl on their knees and badly beat them up; the Kharkiv poet Serhiy Zhadan was also beaten up.

But they managed to keep the police on the Ukrainian side in Kharkiv. Whereas the problem in Donetsk and Luhansk was that the police immediately took the side of the separatist movement; the stock of weapons was seized, and so on. Meanwhile, in Kharkiv, things gradually started to roll back; on some occasions it was the pro-Russian crowd that was outnumbered, and then it was they who were given a thrashing. The pendulum swung in the opposite direction. I made a short film about these confrontations; it is called ‘Regular Places’. It is exactly about these feelings ‒ the unexpected rise of violence of this scale in the city and the impact of the violence afterwards. And it questions whether this violence has already exhausted itself, or is it likely to go on.

Still from the film ‘Regular Places’ (2014–2015)

Could you tell us about the structure of the film?

I witnessed some of the clashes personally. And there were loads of amateur videos on YouTube: everything is immediately uploaded to social networks these days. I singled out for myself five public spaces in the centre of the city where these confrontations were taking place. And then I rewatched all the videos from these spots and started to think about ways of dealing with them. And I realized that I definitely did not want to show any of that in my film. If you speak about violence by way of direct demonstration, all you are doing is multiplying the violence. I wanted to avoid this trap. And so, once the situation had calmed down, I simply started walking around the city filming ‘the quiet life’ ‒ what it looked like under normal circumstances. Everything seemed the same way as before: people taking their children for a walk; someone riding a bike. So I took the sound of these found videos and superimposed the soundtrack on the images of quiet life. That created an impression that the sound is rupturing this peaceful space. Or perhaps that these clashes are taking place right there but a bit further away, off-screen: the result was a bit like a mix of different times. I completed the work in 2015, but I recently ‒ this year ‒ decided to carry on. Many of the same locations have been shelled by Russian artillery; everything is in ruins now. I was there in May and filmed the whole thing. It will be either a post scriptum to the film or a new ending.

The film ‘No! No! No!’ in the exhibition space of the Survival Kit festival of contemporary art. Photo: Ēriks Božis

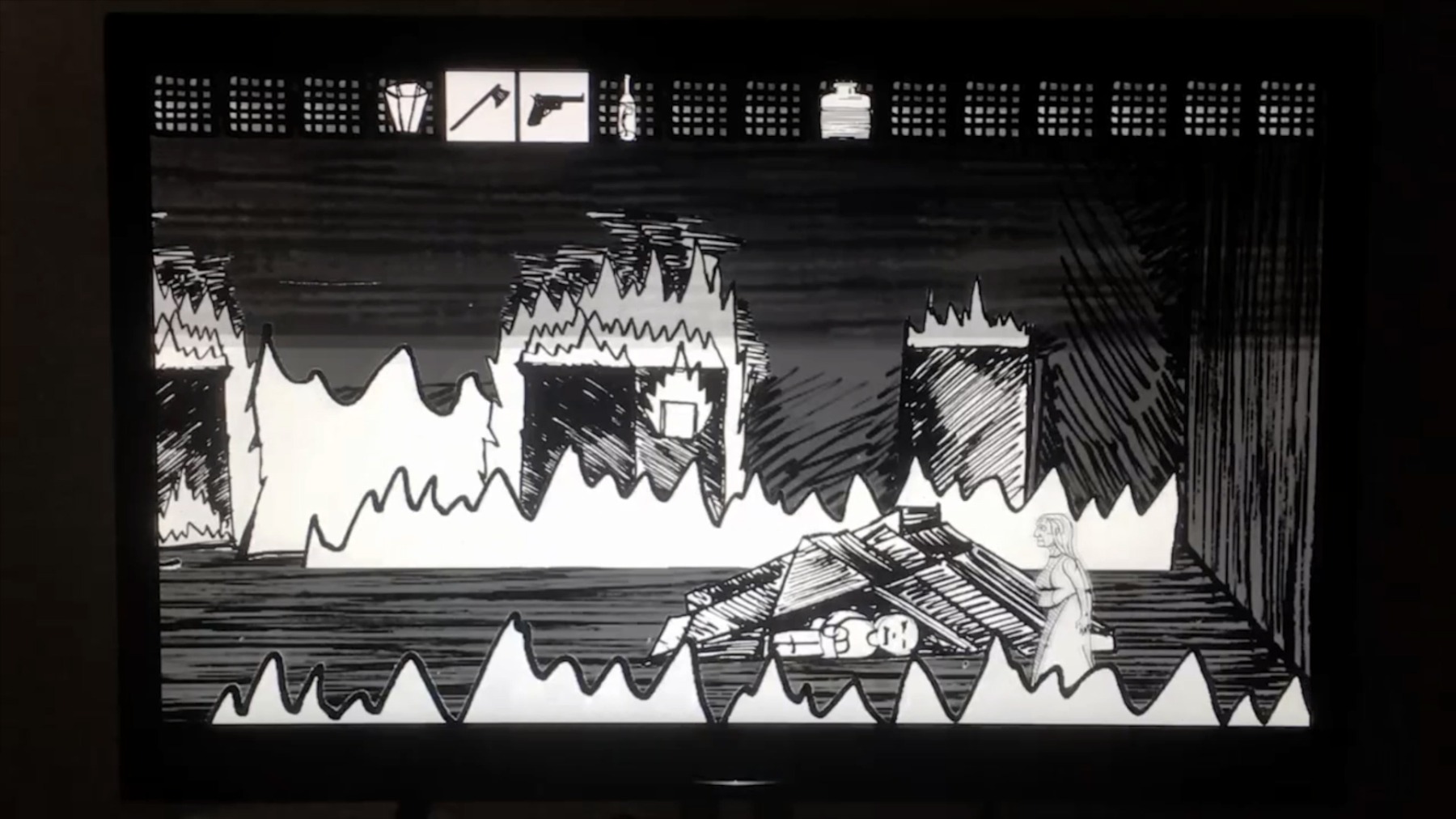

Your film being shown at the Survival Kit exhibition was also shot in Kharkiv, just a couple of years later, in 2017. What is the idea behind it, and what is it based on?

The film ‘No! No! No!’ (or ‘Ni! Ni! Ni!’ in Ukrainian) continues the story of ‘Regular Places’, except the latter focused on space, whereas this one is more about the people. Although it is made in a very collage-like manner, you can discern the structure of four separate small novellas in it. Each of them is dedicated to different young people from Kharkiv. They are all creative people: some of them work in art, others ‒ in the so-called ‘creative industries’. There is a queer poet and activist; there are street artists and a fashion model who tells us about the impact of the war on this industry. And there is an artist who thinks up and develops video games. First, it’s partly just my milieu at the time, although the majority of the people did not even know each other. Second, I wanted to pick people whose daily pursuits have nothing to do with the war. Therefore, the film is not about soldiers or volunteers; it is about these people. Why? To demonstrate that the war has an impact on areas that may seem light years away from the military. The war penetrates these areas as well and changes everything.

It is a film about that time, about the feel of 2015, 2016 and 2017. And what did it feel like? That the war is somewhere nearby but not in the city. There is a war going on in the country but not in the city; there is a certain detachment from it. The city felt that it was not really involved in the war – despite its closeness, despite the military hospital where they treated injured soldiers, or the influx of people fleeing Donbas. To underscore this distance, I inserted amateur videos – found footage by people further away to the east, in Donbas, who were filming the war from their windows. The actual shooting marks a certain distance from the fighting: explosions can be seen somewhere around the level of the horizon. Over the course of the film, they gradually come closer.

Still from the film ‘No! No! No!’ (2017)

A dialogue with a child in one of these videos has stuck in my mind: they are standing by a window behind which shells or missiles are falling and exploding somewhere in the distance in the dark; we only hear these people’s voices. A girl says: ‘Beautiful...’ Her mum: ‘There is nothing beautiful about it. Now listen where it will land.’ The girl answers: ‘Somewhere over there...’

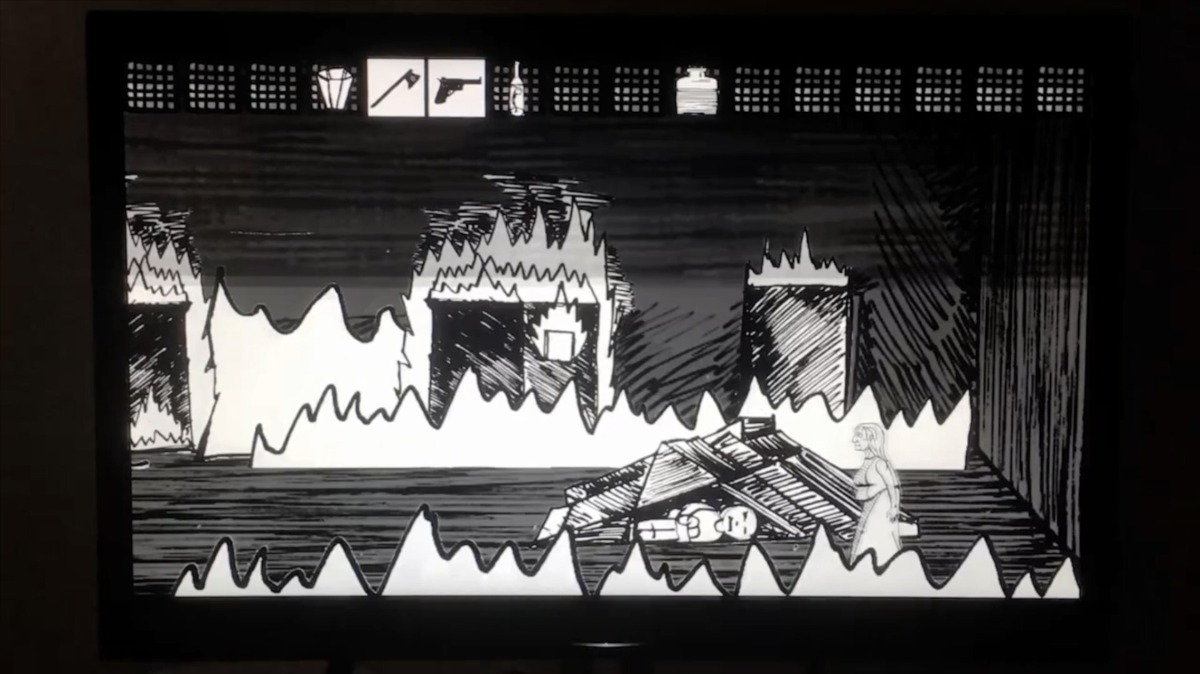

Yes, distance is one of the key themes in the film. And the most prophetic moment, as it was, turned out to be the episode with the video game developer @Marginal act, who created a fantasy game about a fictional city. There is a war going on in this city, with all the logical consequences. It is an exploration game in which you move around in the role of a granny who must somehow survive in this wartime city. Essentially, it is exactly what happened in 2022, when the distance disappeared and one reality was superimposed on another: the war simply spread to new territories, including Kharkiv.

Still from the film ‘No! No! No!’ (2017)

Has this exploration game been released? Is it available somewhere where you can have a go at it?

I am not an expert of the video game market. But, according to the creator of this game, there is a certain circle ‒ quite a wide one ‒ of people who appreciate niche experimental and bizarre video games.

Indie games.

Yes, indie games. So there is the possibility to gain access and play it online. He has created many other new games since.

In your opinion, what is the potential of this video format – one that consists of countless video clips and recordings – to tell us anything about reality? To convey truth in a situation that is being referred to as ‘post-truth’? Can it be truthful?

Perhaps ‘truthful’ is not the right word here. It is not, after all, an investigative film. And I am not even keen on calling it a documentary. Generally, everything I do is ‘documentary-based’ – based on various documentary types of recording reality. The problem is, reality today is not just what we see in the street or what is directly around us. Media reality is almost as real a reality as the street.

Rancière said something that hits the bullseye here: Representation of reality becomes reality in its own right. That is why I try to pay attention to various registers of reality in my works. And since they all intermingle in our life, I mix them all up in my films as well.

As I understand, you used this kind of mixing in your 2020 film about Italy and Ukraine. Could you tell us about it?

The Italian title of the film is ‘Temerari’, and ‘Shibaigolovy’ in Ukrainian ‒ ‘Daredevils’. I did an art residency in 2019 in Italy, in the mountain village of Olevano Romano near Rome. There was this huge villa, incredible weather and Italian food. On the other hand, there was a political crisis taking place in Italy at the time caused by the pro-Putinist right-wing populist Matteo Salvini, the deputy prime minister; because of him, the government was unable to form a coalition. And there was also a very loud court case at the same time which was actively discussed in the media: the trial of Vitalii Markiv, a sergeant of the National Guard of Ukraine. He was a Ukrainian migrant in Italy; when the war started, he went back to Ukraine and joined the army. So he was accused of murdering an Italian journalist in the war zone. Eventually, he was acquitted; it happened two years later when my film was already completed. But even back then it seemed politically motivated to me ‒ an attempt to build an image of a Ukrainian fascist. It eventually came to light that at the time of the journalist’s death, Markiv’s troops were positioned so far from the spot where the incident took place that there was no weapon at his disposal that could have hit the car. Nevertheless, he was arrested and held in prison throughout the trial.

I also learned that the Italian authorities had a group of ultra-right activists on their wanted list; they were in Donbas fighting for the ‘Russian world’. Not a single one of them was caught at the time; they were hiding and seemed in no hurry to go back to Italy. I found the Facebook account of one of these characters; he had found a job as some kind of advisor to the DPR authorities. Basically, this is a film about political paradoxes because there is also the story of Italian Futurism running through the film alongside these investigations. One of the leaders of this movement was Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and initially it was a ground-breaking avant-garde trend; they turned quite conservative later on and supported the fascists and Mussolini’s rise to power. Marinetti himself served as a volunteer in a number of wars of completely imperialist and annexationist nature that were waged by Italy in the first half of the 20th century. Paradoxically, Futurism also influenced the aesthetics of some of the Ukrainian nationalists. So there was this paradoxical situation in which the Ukrainian right admired a phenomenon of Italian culture while the Italian right were fighting against them on the opposite side.

As the war reached the next stage and grew to the extent of a direct invasion, I had my doubts about the wisdom of showing the film at this particular moment, as well as about the best way to present it, because the issue of the Ukrainian right is being actively exploited by Russian propaganda claiming that Ukraine must be liberated from the Nazis. In reality, the ultra-right are not represented in the parliament. It is not the ideology advocated by the power elite; it does not come ‘from above’ but rather ‘from below’. On the other hand, the LGBT movement, the left and many others also operate ‘from below’ – on the grassroots level.

I did show the film a couple of times in 2022 after all, because it touches on a subject that is not explored in the domain of art in any way: the pro-Russian lobby and Russia’s influence on the political circles in Europe. Form-wise, it is a very collage-like cinematic essay, the most collage-like among my films.

‘Lost Baggage’, an installation for the 12th Kaunas Biennial, 2019. It was inspired by a historical figure, the artist Esther Lurie, one of the inmates of the Kaunas ghetto who survived the Holocaust. Lurie made a series of drawings depicting the ghetto’s people, streets, and their living conditions. The artist is supposed to have hidden her pictures in ceramic jars and buried the vessels to hide them from the Nazis. However, the jars have not been found. In his installation, Ridnyi hides Lurie’s images in five human-size ceramic pots. He chose ceramics to reference the ancient artisanal traditions typical for Kaunas. Visitors can only view the drawings through tiny holes in the walls of the pots.

Do you consider your own work to be socially critical art? Or perhaps these categories cannot even be applied to you?

It has been called that, and, on the whole, I do not mind. In the sense of art that turns its attention to social and political processes and attempts to reflect on these issues. At the same time, my personal connections are very important to me. Many of my works are about Kharkiv because it is my native city. And the film I made in Italy contains, in addition to the things I listed just now, this question: How does it feel to be an artist from a country with so many migrant workers in Italy? In other words, I am not just striving to provide a political commentary through my art; the personal element matters greatly to me.

‘Lost Baggage’ installation for the 12th Kaunas Biennial, 2019

What are the subjects you are most interested in right now?

That’s a difficult question. When the invasion started, I was completely consumed by apathy for several months ‒ it was unclear to me what I, or art in general, could even say about all that. And I still have no plans to make new works about the things that are happening right now. It seems to me that I am so deep inside this thing, emotionally and physically (due to Ukraine’s martial law, I can only leave the country for very limited stretches of time), that it is hard to engage in some kind of balanced reflection on these matters. Maybe time needs to pass. A distance in time and space is needed. And I don’t see it coming as yet. I do carry on developing certain ideas I had before the invasion. And it is perfectly clear that, although these works do not directly refer to the war, they will still be seen by viewers in the light of current events. They raise the theme of historical memory, and not just in Ukraine – one of the works is to be filmed in Germany, in Berlin; it will deal with the history of a mid-1930s monument located in the neighbourhood of a housing project for Ukrainian refugees.

Still from the film ‘Grey Horses’ (2016)

Speaking of historical memory ‒ perhaps this is the moment to recall a work of yours in which you explore the figure of your great-grandfather, who was involved in Ukrainian anarchism. What is your vision of him in your film (‘Grey Horses’)?

In fact, he is not actually present in this film as a complete character. I wanted to make this film as an alternative to the conventional heroic epic genre, which is so widespread in the world of cinema. Usually they take a figure and follow their story – the twists and turns of their life. I did not know my great-grandfather Ivan Krupskyi; he died in 1975, and I was born in 1985. I have no idea if he was a good man or a bad man; how much of a hero or a villain he was. And that is why the film is a mixture of documentary and staged footage, and there is no one specific actor who represents him. The viewer is free to guess which of the figures can be associated with him at certain moments of his life. The accuracy or authenticity of the sources on which I based my film are also open to questioning because they are police reports from the 1920s, when the Ukrainian anarchist movement was crushed by the Bolsheviks. Fortunately, my great-grandfather was not killed, but he was arrested. And the facts on which the film was based were taken from his case file, found at the state archives in Poltava Oblast.

But then ‒ what is a police report? A person could hide something during the interrogation, or deliberately try to mislead the investigators. He could have been coerced to confess. The report was written by the policemen. It is hard to tell which part of it is true and which isn’t. One thing we know for sure ‒ he led a life rich in adventure; his story is reminiscent of a thriller. The situation constantly changed, and his role in these events also changed all the time. At 17, he joined the Red Army only to become disappointed very quickly and go on to join the anarchists, who were fighting side by side with the Borotbists ‒ a little-known Ukrainian communist movement in favour of Ukrainian independence. And later, when he was already trying to escape repression, he found a job as a policeman, believing that the best place to hide was inside this very system. Allegedly, he was recognised by someone when he went to try on the uniform ‒ which is quite symbolic. Ten years after the October Revolution, there was an amnesty for large numbers of political prisoners, and he was released from prison. When a new threat of getting arrested arose, he and his family fled to the Far East and went into hiding there.

The film is based on the method of re-enactment: I filmed contemporary policemen, I filmed contemporary anarchists who were setting up their squat in Kharkiv at the time, and I also filmed students and other people who carried out various actions that were related to the situations my great-grandfather had experienced. A critic wrote that it looked like a documentary fairy tale. There is a strong element of fantasy to the film. And this re-enactment ‒ a reproduction of past events in the present ‒ was not done for the purposes of juxtaposing two eras, the 1920s and the present day, but to create a third, parallel time where all kinds of dreamlike events unfold.

Kadrs no filmas “Pelēkie zirgi” (2016)

Are your great-grandfather’s ideas, this anarchist world view, close to your own?

Initially, I had links with leftist circles; I was ‒ and still am ‒ friends with human rights and labour rights activists in Ukraine. It’s just that times have changed, and I think we are now living in an era where the meaning of ‘left’ and ‘right’ has significantly shifted ‒ or even been lost completely. Not least because of the war in Ukraine. The war showed that things that bear certain names can mean something completely different in real life. For instance, I was quite critical of the Azov movement; my objections to them dated back to peace times, when the ultra-right would, for instance, attack Pride parades or teenage ravers. Unprovoked violence in peace-time streets, and their insignia – reminiscent of fascist symbols – were problematic. But today’s Azov is more like a group of professional militaries than an ideological group. It is a division of the National Guard of Ukraine; they have now acquired a heroic image and experience due to the fact that they defended Mariupol till the end. Whereas Russia, where Shoigu notoriously held an ‘anti-fascist’ congress, has appropriated the symbols and rhetoric of the left – but it is no more than a shell, filled with a completely fascist substance. Which means that symbols have now lost connection with their actual content. There has been a substitution of concepts. And the definitions and descriptions that made sense ten years ago are no longer relevant. We must invent a new glossary to escape staying in this vicious circle of violence.

Don’t you think that where interaction with actual people is concerned, we nevertheless tend to clock them as persons with leftist or right-wing views?

I would suggest using phrases like ‘a person with conservative views’, or ‘with a liberal outlook’. As far as ‘left’ and ‘right’ are concerned, the 20th century happens to have left a complicated legacy for us. It was far from the case that every policy implemented by the Soviet Union was a leftist one; on the whole, the USSR was an empire. And imperialism is a concept associated with right-wing principles. Therefore, we should view things through a more complex lens these days; nothing is straightforward anymore.

Still from the film ‘Grey Horses’ (2016)

I recall that in recent relatively more peaceful times, namely, 2016‒2020, there was strong competition between leftist and right-wing ideas. All that has receded into the background these days. Perhaps some kind of new social idea is emerging?

Competition is a good word. And it is exactly what marks the difference between the Ukrainian and Russian situations. There is no such competition between ideas in Russian society. Conservatism and right-wing ideology come from above, from the establishment that instils these ideas into society. In Ukraine, there is an environment of various ideas competing among themselves. And we would definitely deal with the right-wingers on our own. Despite the conflicts, the human rights movement was actually growing and expanding over recent years. Any situation of war is destructive for society; it always means taking a few steps backwards. The results of this rollback will only become obvious a bit later. What we see today is massive solidarity and unity among people with different political views, people from different regions of Ukraine. There is this understanding that what’s at stake is the actual existence of our country. But there is also an emerging awareness that the war will drag on, and it is hard to predict the eventual impact on society.

Do you see in Ukrainian art any projects at a good-quality analytical level that are reflecting on the things that are happening right now? Or perhaps a certain distance in terms of time is necessary for that, as you mentioned before?

I think that, on the whole, the works that are appearing now could be described as activism. I am not saying that’s a bad thing, necessarily. It seems to be the only possible way right now. They carry a direct political message or poster-like content. Some of them go viral and have quite a wide reach. Anything else is probably not very viable at this stage. My advice to artists would probably be to take some time before making new works on the subject of war.

‘Blind Spot’ on the façade of Kunsthaus KuLe. Berlin, 2014

You mentioned Serhiy Zhadan when you were speaking about Kharkiv. I know that you and this first-rate poet once did a joint project.

I have this work that I made early in the war, in 2014; it is called ‘Blind Spot’. It occurred to me back then that all this access to information and the lightning speed with which war-related visual information appeared – for instance, images of the aftermath of a bombing – actually did very little to get us closer to the whole picture of the things that were going on. Because the media space is very manipulative. I noticed that the same image could be used by both parties in the conflict with a completely different message. I started downloading pictures from the war in Donbas that had been posted by various news agencies. Alongside that, I was also interested in various aspects of human eyesight ‒ the facts about the process of looking at things from a purely physiological angle. So I started reading about various eye diseases, specifically about scotoma. And this ‘blind spot’ in the title of the work is an area between our left eye and our right eye where we genuinely cannot see anything. Our brain does all the work to fill in this space, matching it to everything we see around it and to our past visual experience. We have no idea about any of this; everything happens automatically. We only start to realize this when something is wrong with our eyesight. As a result of certain eye diseases, this blind spot can appear as a foggy area or a black spot.

I took a paint can for graffiti and tried spraying areas of these photos, imitating the effect of these eyesight defects. And in 2014 in Berlin I was invited to make a large banner on the façade of a building. It was around the time that I had this idea to collaborate with Serhiy Zhadan, because we are both from Kharkiv ‒ to create a detail that would allow for immersing in the context more thoroughly but would only become visible when viewed close up. I picked an image of a destroyed building in Luhansk Oblast, and Serhiy wrote a text about an annihilated museum from the same region. And we hung it on the façade. Later we made a whole book together in the same spirit.

Still from the film ‘Grey Horses’ (2016)

How do you build the ‘text‒picture’ interaction in your works? I mean the text spoken by your characters.

Speaking of interviews with characters or protagonists, I have always found it very boring to film ‘syncs’, like they do on television. It can be solved in various ways, for instance, speech can provide commentary on action. Probably the most interesting technique I have used was employed in the ‘Grey Horses’ film, where I wanted to include quotes from my great-grandfather’s trial. The language of these court records was very specific, quite different from the way they would speak in court today. I spent a long time considering ways of doing this ‒ should I use a narrator’s voice-over, or perhaps subtitles? Finally, I turned my attention to this thing they have running on TV news editions – the ticker. It is out of sync with what the news anchor is saying: it is another text completely, and you must take in both feeds of information at once. I found it very interesting. So I introduced this running ‘ticker tape’ into my film, on various levels of the screen, at that. Sometimes it crosses out people’s faces; sometimes it is more traditionally placed underneath. Afterwards, when I was working with the film editor, we realized that the ticker was very reminiscent of a telegraph tape. Although inspired by a completely contemporary thing, it was also a reference to something from the past.

Mykola Ridnyi. Photo: YermilovCentre, Kharkiv

And, most likely, my final question: Why is it important for you to show your films in the environment of contemporary art ‒ at exhibition spaces, art galleries... What does it add to the films?

I suppose it is probably simply because it is a more open environment. No offence to the film people, but I find cinema circles much more conservative than the world of contemporary art. There are certain canons in film, and people constantly go back to them. When film was born as a medium, it was a synthetic genre at the intersection of theatre and photography, capturing a moving image. Time goes by, and it would seem that the genre should go further in its process of synthesis, but it has not been changing very much, in my opinion. It still gravitates toward its traditions. Whereas contemporary art is an area that constantly keeps regenerating through the courtesy of other fields. It is constantly questioning its own nature. And through this questioning, it is pushing back its boundaries. I find more innovation, more constant re-examination of boundaries, more doubting ‒ and that’s very important for moving forward.

However, my films have been shown in cinema auditoriums. And I am interested in doing that again in the future. It’s just that I don’t see any room for myself in what cinema is doing within the mainstream. There are, of course, more experimental and niche film festivals and initiatives. On the whole, my films exist somewhere at the intersection of an exhibition space and a cinema – somewhere in the middle.