How is «atelienormalno» doing now in Kyiv?

We talk with Ukrainian artists Kateryna Libkind and Stanislav Turina about their pre-war and current experience of interacting with their colleagues with Down syndrome

I first heard about “atelienormalno” from Lisa Biletskaya, who had to flee Kyiv together with her cat and, through Hungary, came to Latvia. She told me about her friends’ project with much affection and respect. “ateliernormalno” was founded by Ukrainian artists Stanislav Turina, Kateryna Libkind, Valeriya Tarasenko and Olena Vasyk. A series of classes organised in 2018 by the Goethe Institute in Kyiv served as an impetus to its creation. It was during these classes that Stas and Katya first met their colleagues (this is a very important word, and we will use it throughout the interview) – artists with Down syndrome.

Anna Litvinova working in her studio

Stas and Katya are the bride and groom. Both are artists who play their respective roles in the Ukrainian art process. Born in the Donetsk region, Stas grew up in Transcarpathia. He’s a member of the well-known “Open Group”, the one that presented the project titled “The Shadow of Dream[1] cast upon Giardini della Biennale” at the Venice Biennale in 2019. A giant Ukrainian plane (destroyed this February in the battle of Hostomel) was supposed to fly over Venice and cast its shadow over the city. The flight did not take place, but the discussion and mythology around it became the essence of the project. This is what Turina’s fellow artist Yaroslav Futimsky says about him: “He’s got this ability of turning practically anything into a piece of art, and he doesn’t even have to bring it into an institutionalised space.” Stas engages himself in graphics, performance, installations and dance. “I see the world by digging in the ground, crushing a dried piece of earth between my fingers,” – so the artist put it in his interview in 2020.

Katya Libkind earned her degree as a theatrical designer, and her most notable works of recent years include three operas staged in Kyiv by Ukho music agency. She not only designed the sets for the operas but also directed them. In 2021 she summed up this work in a show called “Minerals: Exhibition of Operas in the Pavilion of Memories”. Katya loves a “small gesture”, and often gets involved in art outside the gallery. She works in installation, performance, land art, painting, graphics and video.

Kateryna Libkind and Stanislav Turina

Kyiv curator Elizaveta German, one of the people who encouraged the creation of “atelienormalno”, notes: “It is important to say that the atelier teachers do not tell their students what to do and how to do it, what topics to address, nor how to interpret them. Rather, they show the possibilities of various techniques and media.” The atelier’s current crop of young artists are: Anna Litvinova, Evhen Holubentsev, Valentyn Radchenko, Olexander Steshenko, Anna Sapon and Irina Holoborodko. All of them are persons with Down syndrome. “It’s not a disease; it’s not something one can contract and then be cured from. It’s just a genetic trait,” says Elizaveta German.

The works of the studio members have already found their way into private collections as well as Ukrainian and European galleries and museums. Some have also been presented at international film festivals. During the pandemic, the artists of “ateliernormalno” continued their studies, had some plein air sessions, and kept communicating with their colleagues, often online. Several new exhibitions were scheduled for this March. But instead of a period of post-pandemic “normalisation”, a cruel and deadly affair has started – Russia’s war in Ukraine. On an April evening, I had an online session with Stas and Katya and talked about the war and how it has affected the activities of “atelienormalno”, how their colleagues with Down syndrome have responded to this situation, and also about their volunteer experience in the Kyiv psychiatric hospital named after Ivan Pavlov, founded in 1786 and considered the largest in Eastern Europe.

Evgeny Holubentsev’s work

How did this whole idea of “atelienormalno” come about?

Stanislav Turina (ST): You know, I’ve learned several sentences literally by heart over the years… Well… It started quite by chance – our friends, curators Maria Lanko and Elizaveta Herman, asked us to conduct a series of classes. It was 2018. I don’t know how it is in Riga, but in Kyiv, artists often get involved in various part-time jobs – several days of side work which allows them to do their own thing for several weeks or to pay the rent, for example. Katya and I agreed to come. And when we came to these classes, we saw three persons with Down syndrome – as well as a lot of people without this syndrome. Our future colleagues from Ohrenkuss magazine were there too – they work together with the Touchdown21 research centre [based in Germany – Ed.], which for more than 20 years has been studying Down syndrome from every possible angle. Representatives of the Down Syndrome Ukraine charity, who had helped to bring all the participants together in Kyiv, were also there. The German institutions are both based in Bonn. And it was not by chance that they came to Kyiv, because besides presenting its own projects abroad, the Goethe-Institut also provides space for important and interesting initiatives so that local groups can think about how to implement the Germans’ experience into their own projects.

In 2018, if you had googled “artist with Down syndrome in Ukraine”, your chances of finding something interesting would have been small. But the proportion of people with this syndrome is approximately the same all over the world. It is by far the most common chromosomal abnormality.

Our colleagues invited us to participate in this event because their methodology suggests that a four-hour interview is a difficult task and quite a workload, but the art making process implies working with images and helps to continue the conversation in a different spirit. While working there we met Zhenya Holubentsev. Now we may call him a brilliant artist, but even then we were shocked – in a good way. And that’s what made us decide to go forward with our classes. Gradually the project grew bigger, and using the same technique Tom Sawyer used to paint a fence, it engaged more and more people. Now the atelier includes 12 persons – plus a fairly large circle of “sympathisers”.

12 persons both with and without the syndrome?

Katerina Libkind (K.L.): Yes, there are six artists with the syndrome and another six without it. And sometimes those without the syndrome assist, and sometimes we work as equals.

How did you come up with the name “atelienormalno”? Did you use it from the very beginning?

KL: One of our colleagues with the syndrome, Valentyn Radchenko, is quite a laconic person. When we ask him – "How are you?", his reply is: “Normal’no”, which means “fine.” And atelier is the German word for “studio”. Since we started working on the project with our German colleagues, this word kind of stuck.

ST: On the one hand, the word “atelier” brings about some confusion. In both Ukrainian and Russian this word is related to fashion. On the other hand, when we started calling ourselves just “Normal’no”, it sounded weird. “Hello, I’m calling you from “fine” We…” – “What?!” The word “atelier” seemed to smooth this linguistic dissonance.

This also relates to the normality / abnormality issues, or what is considered “normal”.

KL: Yes, of course, that’s why we took this rather broad concept. What does it mean to be “normal”? You have to constantly figure it out. And at the same time, “normal’no” defines a situation when things are neither good nor bad, but normal.

ST: Talking about normality… There is a Ukrainian word “pidvazhit’” – to lift something, to turn over, to pick at. And our colleagues’ speech is quite specific – regardless of topic, even when we talk about ordinary, everyday affairs, the things our colleagues say turn over and shift the familiar picture – sometimes they even reinvent the meaning of words.

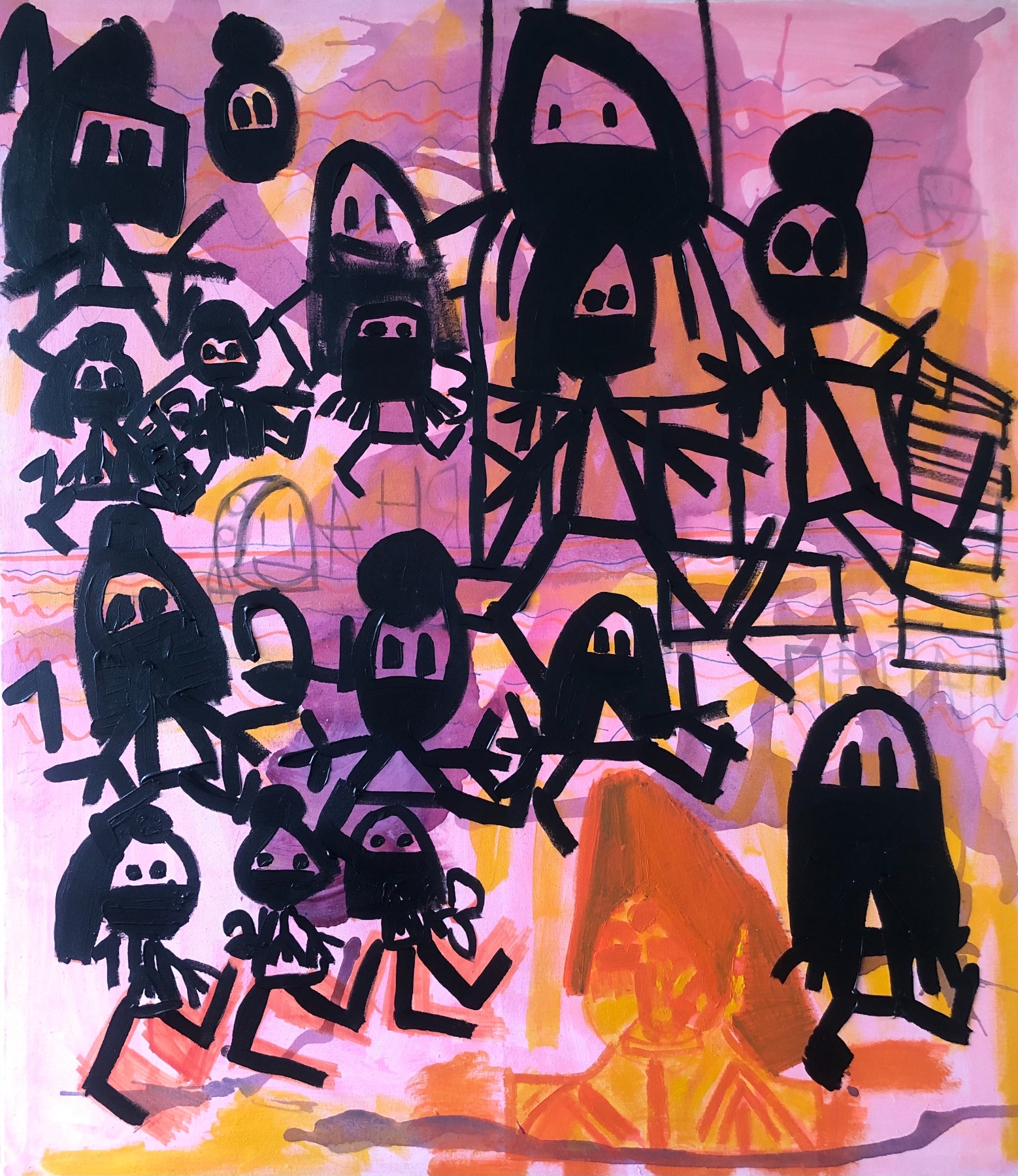

Dacha Diary residence

What kind of artistic practices do you use in your work? Collaborative drawing or something else...

KL: We all share a large studio on the 18th floor, with round windows overlooking Babi Yar. And the group members come to work there when they can or want to. Due to COVID, we didn’t get all together much – more often we worked in pairs: an artist with the syndrome and an artist without it. Sometimes each would do their own things, sometimes both would work together on a shared theme. We use many different media – there are artists working with painting, others use collage or texts or embroidery. One of our team members, Sasha Steshenko, is a screenwriter – he’s written more than 50 scripts, and we even made a movie based on one of them.

ST: All of us without the syndrome work in contemporary art and are known in certain circles. Most of us have a considerable exhibition or curatorial history behind us. So it’s not that we just “meet and draw”. This year, for example, we organised a Ukrainian-German nine-day online residence. Three teams from Germany and Ukraine stayed in their respective residences and explored the ways they interact within the teams. It was like a research institution working from three different places. Like a giant offline/online symposium. Each of the 12 colleagues dealt with their own subject. Sasha Steshenko, for instance, held three colossal performances, and managed to hold the audience’s attention for at least an hour and even involve them in some interaction. It all went without any preparation or rehearsal.

KL: This improvisation seems to flow out of him, and there are no barriers to it.

ST: As a result, some completely unpredictable things happened. For example, some with the syndrome improved their speaking abilities – within these four days. Even though we have nothing to do with speech therapy – it is not an area of our immediate interest.

The video Ekaterina Libkind made during one of the “atelienormalno” residences . Become a Patreon subscriber for “atelienormalno” and get access to more of these videos.

That was supposed to be my next question: what do your colleagues with the syndrome get from these practices?

KL: Firstly, the fact that they are here on their own, that their parents are not supervising them, and that they run their own projects – it gives them a sense of responsibility. Their abilities are much greater than their families, who often take too much care of them, allow them to have. Of course, their worries are partly justified. But people with the syndrome are capable of doing things themselves, and building relationships is one of them. When you live with your mother and spend all your time with her, you are unlikely to develop relationships with other people. During the residence this became quite clear. For example, the fact that they are polygamous in their affections.

ST: Their rhetoric, the flirting system our colleagues with the syndrome developed, made it clear that constructs such as “this is my only love for the rest of my life” are quite foreign to them. It’s rather “Right now I love this person more than anyone else in the world,” but I can still feel even greater love for others. And these things do not contradict each other. Thus, through them, we learn more about the culture we live in. Because our colleagues are not only, in a sense, prisoners of their families – they are also prisoners of our culture and prisoners of their respective situations.

Now we volunteer at Pavlovka, a mental hospital in Kyiv. People who stay there can neither use the internet, nor call their relatives. Not that they are banned from doing so – it’s just that they cannot make the correct request on their own. For an immediate need, a person has to wait for two weeks until those in charge find the time to do it. Such things make one’s life a prison, one where life becomes a constant waiting for either a good overseer, or a visitor, or a missionary who comes one day to rescue him from this endless dependency.

I must say that when the war started, our colleagues with the syndrome showed themselves in an interesting way. For example, Valentin Radchenko usually misses us and really wants to see his colleagues. He lives in a more or less safe suburb of Kyiv; of course, some explosions and shelling were heard there, and he saw what was happening in the skies. And yet the invasion didn’t reach his town. But now he is not interested in talking to us, and it’s been like this for a month and a half. I never thought it would be Valentin who’d not want to talk to us. He’s not offended or upset, he just seems to have nothing to talk about with us.

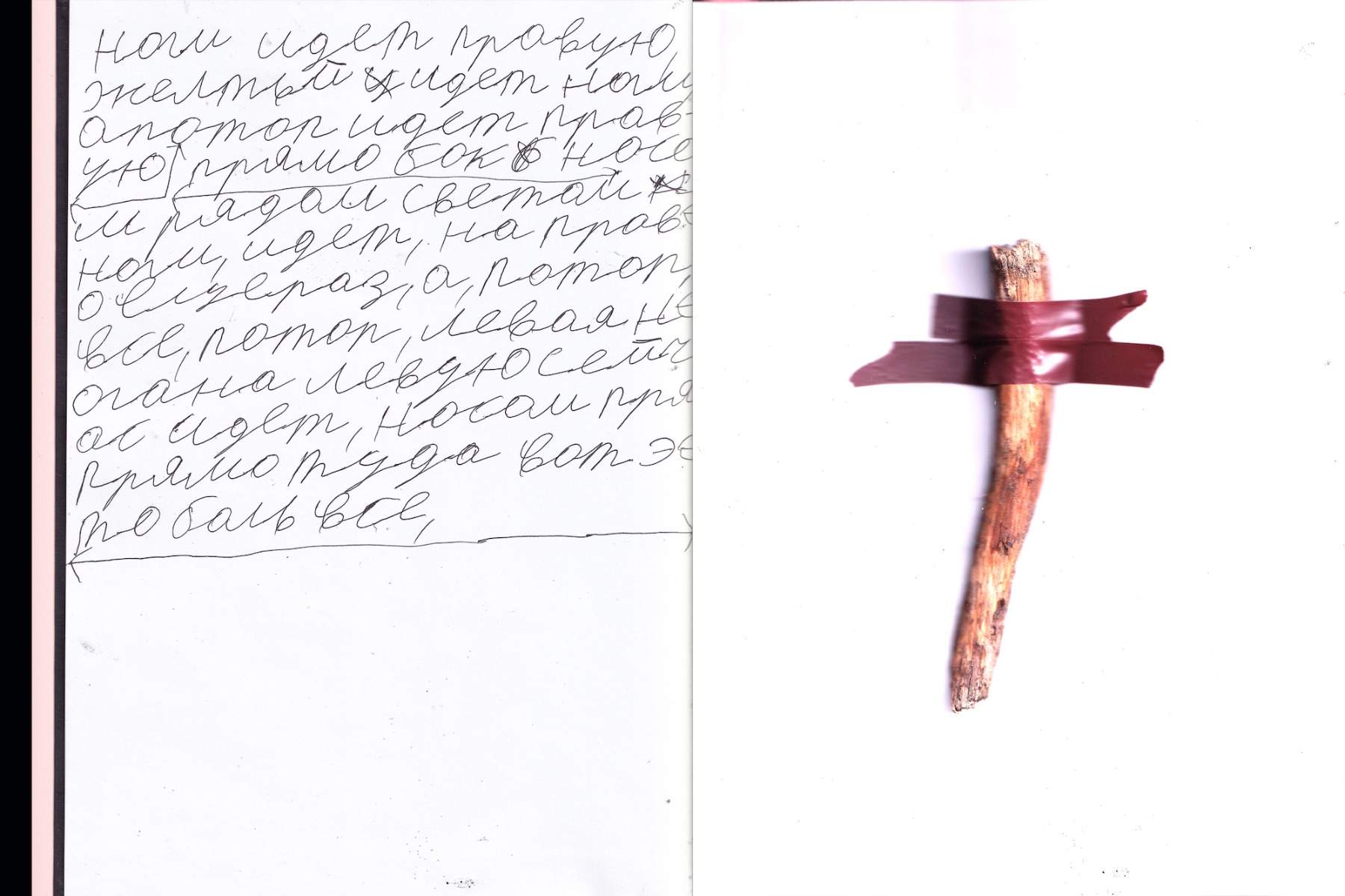

A page from the diary-herbarium of Valentin Radchenko

Do you mean his attention has switched to something else?

ST: I often talk to his mother to offer some help. There are many options to leave the country now – our colleagues from Germany can also offer such possibilities. So I call them now and then to ask if they need anything. I often ask to pass him the phone. Or to tell him something or call me back. But Valentin neither calls me back nor does he pick up the phone. He doesn’t need to talk to me now. I suppose he’s busy reflecting and experiencing things.

Or Sasha Steshenko, who usually talks a lot. We have even devised a regulation for him indicating the number of calls allowed per day. And suddenly it turns out that he is not at all the one who needs help in this situation. And this generally applies to other colleagues with the syndrome. It was very unexpected. Rather it’s their calmness that supports me now.

Flowers in a Blue Vase by Anna Sapon

Could it be a sign that the war has made them shut themselves in?

KL: It’s possible, but unlikely. Because in all the time we’ve been working together, we could always make any of our colleagues leave their isolation by simply talking to them.

ST: There is some other kind of shutting down happening here, which is now common for all Kyiv and even all of Ukraine – there are things that you simply cannot talk about. Or you can hardly find the words. There is also military censorship. We were warned not to talk about certain things. Our colleagues are aware of this, and it can also influence their behaviour. But they continue to write texts, kind of like diaries.

KL: Sasha writes his scripts. Zhenya draws. He was trapped. The village of Vablya, not far from Borodyanka, was occupied. We lost connection with him on March 3. As far as we know now, he’s been drawing all this time. For him, drawing is the language. He does not speak very clearly, so drawing for him is both a diary and a major link to the outside world.

ST: We were very worried for him, he was supposed to have a solo exhibition...

KL: So it happened that for the whole month of February, until the 24th, I was preparing Zhenya’s exhibition. It was supposed to be about cemeteries. It was about signs of death, about dates. And I was supposed to curate this exhibition. I’ve been thinking a lot about Zhenya all this month. And when the war started, and the connection with him was lost, I continued to think about Zhenya, only in a completely different way. Once I went into the studio, and all of his works were there on the floor – they looked like a memorial.

ST: Zhenya is already in Kyiv; he spent a month in the occupied region. His family is alive, and now they are going through the stage of learning what’s been happening, because for a month they didn’t have any news and didn’t know what was going on. We learned that our colleague and his family were alive the same day we learned about Bucha. They survived by some miracle. They were in the village of Vablya, near Borodyanka, and the world has yet to know what happened there – minelaying, blockages... Yesterday we saw a friend from Mariupol, and it was so weird to talk to him as if nothing had happened. We also planned to make several shows in Kherson – we’ve already done exhibitions there. Ukrainian psychogeography now is like bending your fingers for the people you know and for the cities you were familiar with in your old life before you go to sleep. Zhenya himself is very religious. Religion is also one of his key themes, and that’s probably what made us keep our faith.

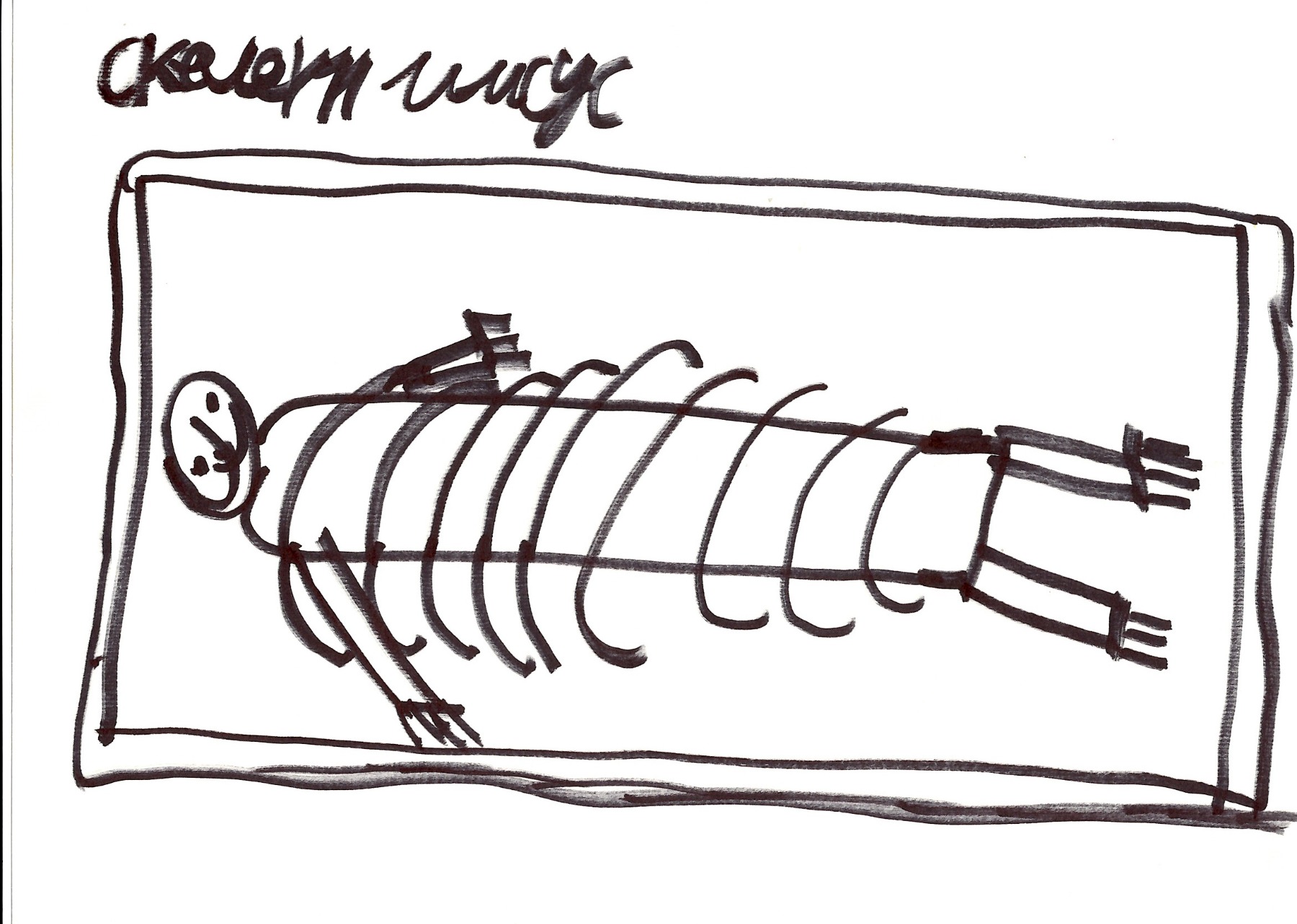

Skeleton of Jesus by Evgeny Holubentsev

Do your colleagues with the syndrome get especially interested in certain topics, or is each person a planet, each person’s interests are unique, and generalisations are out of place here?

KL: I’d say the latter. Usually, when we start talking about topics, we talk about each artist separately. If they coincide sometimes it’s because they are friends, not because they have the syndrome.

We’ve made an exhibition of Valentyn Radchenko’s works in January. The theme was household items. He is a serious collector. He collects handles from old Soviet refrigerators, as well as soldiers and postcards. He puts them on a piece of paper, outlines them with a pencil or pen, then paints them over and calls them by some name. He arranges them on the surface according to the way these names and phenomena correlate, in his opinion, in the real space of relations. This is named “Kolya, Vanya and the Scorpion”, and they are located in exactly the same position as they, in his opinion, exist in life.

ST: It’s a kind of psycho-installation.

KL: His very speech is arranged in this way. It can be imagined as a landscape where all these words are arranged by colours, by hierarchies, by height, by thickness. And these words for him are items for a kind of installation. Sometimes it seems that the chronology of speech gets in the way. That he wants all the words to be pronounced simultaneously. And this is what happens in his work.

Sasha Steshenko is one of the most socially active artists of the group. He prefers more sensitive, more sharp, socially significant topics. He writes a lot about international relations, different countries, and heroism, as well as women (“such nasty creatures”) and how to gain their affection. That is, he works with stereotypes, his own stereotypes, the ones he absorbs. But they are so dense in his texts that their meaning seems to be refracted, so to speak. Or, like Nikita Kadan put it, “a stereotype that leads itself so deep into the forest it can’t find the way out.”

ST: It brings itself to such a degree of absurdity that it ceases to work.

KL: When a stereotype is not embedded or enveloped in our speech, when there is nothing else besides the stereotype, it starts acting differently.

A still from “A Souvenir of the Lost Love to Antonina Nikolaevna” written by Alexander Steshenko

A stereotype that bites its own tail... And twists into a spiral.

KL: Yes, exactly. I have already told you a little about Zhenya Holubientsev: one of his main themes is the cemetery, death, and everything around it. His second theme is war, catastrophe and religion. But he basically draws everything he sees.

ST: There are convergences among them. Some are interested in transport. Anya and Zhenya like images of animals. Some like landscapes.

KL: But they still draw them as if looking through their own lenses. Zhenya draws things that simply fall into his field of perception. And Anya Sapon draws because, in her opinion, it is beautiful. So those convergences are rather formal.

ST: Sometimes they are inspired by each other. But in general, people with mental differences are isolated from the world as much as from each other. For example, during the residence, we experienced quite an unexpected problem: they do not get along with each other easily – they shared few common themes and the space of contact between them was limited.

KL: That is, if artists with Down syndrome are left alone, it can lead to a scandal.

ST: So we comply with certain rule systems, systems of restraints that apply to both collective and individual work. This experience has also helped us in Pavlovka during the war – where we have been working for more than a month now. It may seem odd, but life in the mental hospital has not changed much.

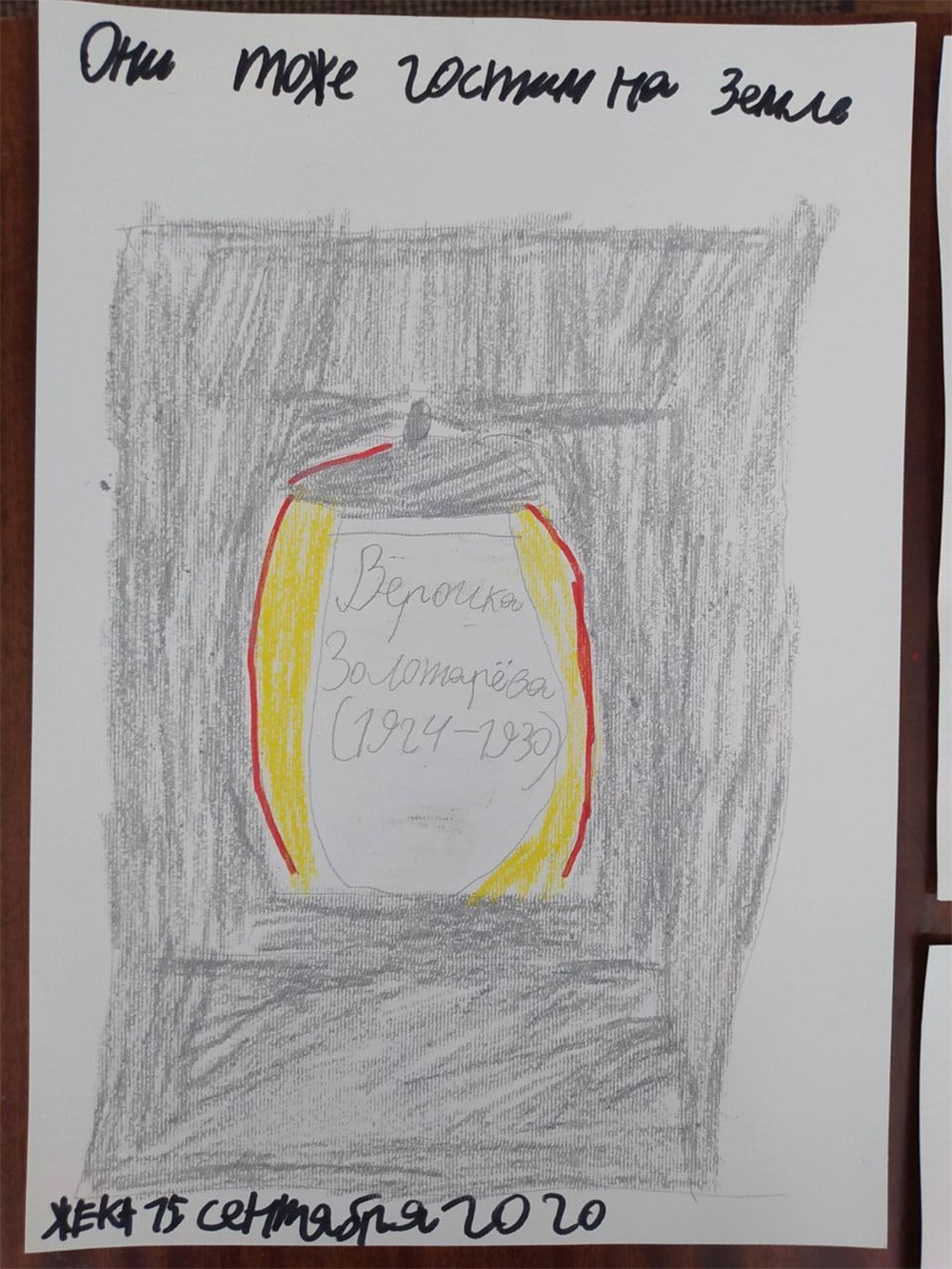

Evgeny Holubentsev’s work

Do you mean because of the war?

ST: Yes. That is, everyday life has not changed much for people with mental disabilities, probably because they have been constantly waging their “everyday war” in a sense – with their life, with their body, with communication constraints, with barriers, with treatment. And I think it’s very interesting to reflect on professions and how they change in times like these... The issues we have to deal with in the mental hospital are like the following: we need tables, we need notebooks, we need flowers, we need rakes. So things could be good, normal. It’s quite a weird feeling. But it also brings us to a certain level of normality. It is normal to think about planting. The sowing campaign is in full swing now – the sowing campaign in the country at war. In the mental hospital we use the same approach – we do what is needed. This brings you to the key items of existence. To the things life is based on, the things we need to keep on doing one way or another. This is quite an interesting experience for both rehabilitation and civilizational nature.

Did you decide to volunteer at the very beginning of the war?

KL: We just got a message that they need help there. About 150 people had been evacuated to Pavlovka from the psychoneurological dispensary in Pushcha in Kyiv region. They needed emergency assistance because all of the patients were placed in a single department, with no possibility of giving them additional wards. Can you imagine? 150 people in a corridor, and many of them can’t walk by themselves, can’t eat by themselves, and so on. Now it’s getting better – all of us did something to cover such gaping holes. But we still buy things they need and bring them there.

ST: The first thing we did (together with the staff and other volunteers, of course) was to shave and cut everyone’s hair. They had been unshaven for a month by then. And as soon as we shaved them, it felt like it became easier to breathe. There was one guy who really wanted a radio. And for a long time we could neither buy one nor get one from friends – very few people had stayed in Kyiv at that moment, most were elsewhere. But as soon as we got the chance and brought this radio, he said: “Stas, you have no idea what you’ve done for me.” Of course, they still can be moody sometimes, but somehow it does not linger for that long. Can you imagine that a single radio could change the lives of 60 people?

KL: The radio is not the only thing of course... When the situation improved and the essentials had been provided, it became vital to come up with some kind of leisure. Because all they do during the day is sit there, looking at each other, mooching cigarettes from nurses and waiting for their food. That’s all the entertainment they’ve got – cigarettes and food.

First we brought some books, then some drawing materials. And, in fact, we’ve just set up another atelier there [laughs]. Twice a week I visit one department, twice a week another. We talk, look at books, listen to music, and those who want to, draw. And those who don’t just hang out with us, telling us things. At first, five to nine people came, but today it was almost twenty. They’re waiting for me like I’m their event of the week.

ST: They wait for Katya as if she were The Prodigy! When she comes, she brings good vibes with her. The steps we took in this month and a half (not only the two of us, of course – there are many more volunteers and there are those who help from abroad), steps that lead to a normalisation of life, are very similar to what people would do to resume normal life in general. Hygiene, food, some goodies, a haircut, a shave, new shoes… As soon as we brought everyone slippers, it was like… It’s one of the elements of happiness. Slippers. A radio, a ball, a library, music and, of course, strolls. And this model can be used to resume the life of an entire city. It is a kind of civilizational basis that helps make the temporary premises they’re occupying into a home.

KL: These people are not from the hospital – they come from the psychoneurological dispensary [a mental health unit – Ed.], which they will never leave.

ST: Unless their families take them back one day...

KL: But now they’re practically trapped there forever, and they can’t do anything unless the nurse asks them to wipe the floor or something. And yet most of the people there, those who are able to walk and talk, are very efficient. And they could perform various functions, but they rarely get that opportunity. So that’s why all of their energy goes, as I said, to mooching cigarettes and waiting for their food. Yet they could have been taking care of themselves. We were thinking about how to make this whole system include patients and let them work there, in the hospital. They really want to be helpful. I think a lot of people are under enormous pressure, feeling that they cause problems for the nurses and for society in general. And everyone around makes them feel this way – feel that they do cause problems.

ST: But when tables and chairs come into sight, these bring possibilities – to sit, to do something on your own, and suddenly it changes everything. And this reveals to me a kind of metaphysics of things.

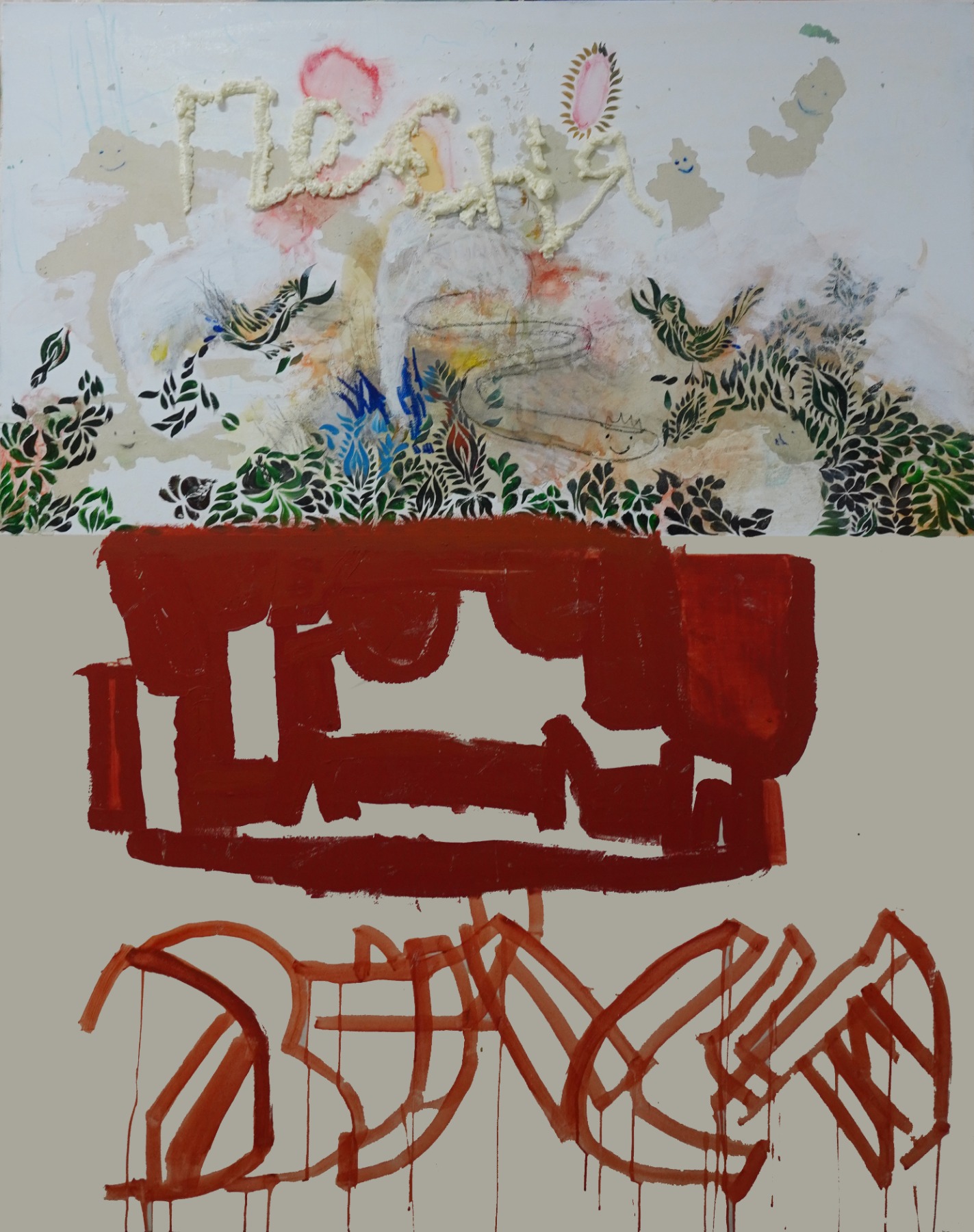

Diptych by Anna Litvinova and Katya Liebkind

Do these discoveries somehow influence your own works, your artistic practices?

ST: A table is something I need too [both laugh]. My own work desk.

KL: They do influence us because our artistic practices are directly related to what we do in the atelier. For example, Stas did a joint exhibition with Valentin, which was in January. I curated this project. It was a kind of diptych exhibition. I started a big project myself and also used the diptych format. We take a canvas, divide it in half, and give one half to one painter and the second to another. Their stories are completely unrelated. So you get two independent paintings in one. And to a very interesting effect.

ST: It’s high time to say a few words about our colleagues. For example, Lera Tarasenko has made quite a series of diptychs with Zhenya Holubientsev. She was the first to join us. For her, Zhenya is a very important artist – he has also taught her something. The important thing about the atelier is that we are not engaged in therapy or charity. Every artist works with those he is interested in, and only when he or she needs it. This activity is completely voluntary. We learn from each other. Our colleagues with the syndrome get a completely different level of attention towards them. And the attention they pay us in the atelier or in Pavlovka is of a completely different quality compared to the attention they pay to the nurses, for example. These kinds of attention are fundamentally different in register and speed.

KL: Talk about using difficult language... [laughs].

And one more thing… There is a so-called “simple language” designed to facilitate communication with people with disabilities. It also teaches us to speak clearly. Sometimes we have to explain quite complex things to our colleagues in a very simple way. This experience helps us a lot in our life too. We even started a minor movement last year for the simplification of contemporary art language. And this is not about reducing meaning, but about reducing complex language where necessary. This is about open society.

Everyone is wearing masks, Lera! by Valeriya Tarasenko, Anna Litvinova. 2021

Do you mean the formal language of art, or the language in which art is described and analyzed?

ST: I mean the text. I once was a member of an art group whose practice was based on the Open Form theory by Oscar Hansen, a Polish architect. Many Polish artists came out of this theory – Pavel Althamer and Artur Zhmievsky, to name a few. What I’m trying to say is that in any project, your colleague becomes your co-author. There is some kind of hierarchy, of course, someone starts a project, someone finishes it. But you constantly read and consider the signals coming from those you work with. You just can’t close yourself up. Therefore, in “ateliernormalno” we develop the working rules.

KL: I’ve just realised how the atelier influenced me. I used to be very shy in expressing myself textually – even in an interview. I wouldn’t develop my thoughts even on Facebook. And while working in the atelier, I stopped being shy about my own thoughts, my own words. I taught myself to notice this moment of embarrassment and analyse it.

ST: I totally agree. Lera Tarasenko, our colleague we have already talked about, also began writing at the residence this year. She says: “If our colleagues with the syndrome write freely, and it’s interesting, why should I be ashamed of my words, whatever they may be?” We work responsibly and without censorship.

Another thing that the atelier did to me was to make me a true citizen of Kyiv – with a sense of responsibility for this city. I can’t say now: “It doesn’t concern me” or “It doesn’t matter much.” I can still say that a lack of knowledge doesn’t allow me to work properly with some issues such as old architecture or the necessity of bike lanes. By the way, I began to ride a push scooter to Pavlovka and started thinking of setting up a company to produce special curb segments for the convenience of scooter riders.

KL: The atelier made me openly express myself in text, but it also influenced my art – it became more political.

ST: That’s probably the case for all of us…

KL: I really used to consider myself apolitical [laughs].

Dacha Diary Residence. Plein air

So this sense of responsibility is now manifested at this level too.

KL: Yes.

ST: We are responsible for those we walk side by side with. And these people speak so boldly about some things... We must not let them down. We must keep up with our colleagues’ level of seriousness, their level of responsibility.

You know, our colleague S. (he preferred to remain anonymous) wrote a letter to Putin in the first days of the war. I don’t remember how we came up with this idea. I sent this letter to my Russian colleagues. To keep on the safe side, I shall not name them. And they said: “Sure, we will publish it.” It was at the end of February, the first week of the war. Then it became clear that it would not be possible – many media outlets refused to publish it. We wanted this letter, handwritten on a piece of paper, to reach the addressee. But we were told it’s most unrealistic. S. himself is quite a Russophile – he loves Russia, he has birches all over his screensaver. And so he wrote a letter: “Whom are you killing? We come from the Volgograd region, we are your kin. Are you by any chance a relative of Hitler?” He has an amazing style. It makes you cry and laugh. The letter was finally published by Boris Vishnevsky, a St Petersburg deputy, in his Telegram channel. He even answered this letter. So if a colleague of mine writes a letter to Putin, what should I do? How can I match that? You can’t possibly be an irresponsible person in such a situation. You have to become more confident.

***

[1] “Dream” is the literary translation of “Mriya”, the name of the Ukrainian aircraft which, before its destruction, was the largest aircraft in the world.