Art has to be a tool to understand the world

An interview with French artist Laurent Grasso

The works of French artist Laurent Grasso are a constant testimony to the fact that there is no frame for reality. By refraining from judgment and maintaining the distance of an observer, Grasso merely reveals ever new layers of reality – like a kind of Maya veil – of things, processes, and phenomena, our preconceptions of which have been formed by our stereotypes, fragmented private experience and also sometimes inaccurate or even deliberately skewed information. He also challenges the classic artist’s “framing” within the comfortable cell of the art world. Grasso is convinced that contemporary artists cannot afford to practice decorative escapism; they must be intellectually strong and equal partners in decision-making, and they must be visionaries who use art as an instrument to help viewers understand the world.

Throughout his career as an artist, Grasso has been interested in physics, philosophy, alchemy, anthropology, science fiction, and paranormal phenomena as well as contemporary mythologies and rumors and how they interact with reality. In his artwork, he is in constant dialogue with people from these diverse fields, and he constantly pushes himself and viewers outside their comfort zones. Each of his works, from sculpture to video and painting, is a kind of research project that exists outside of usual experience.

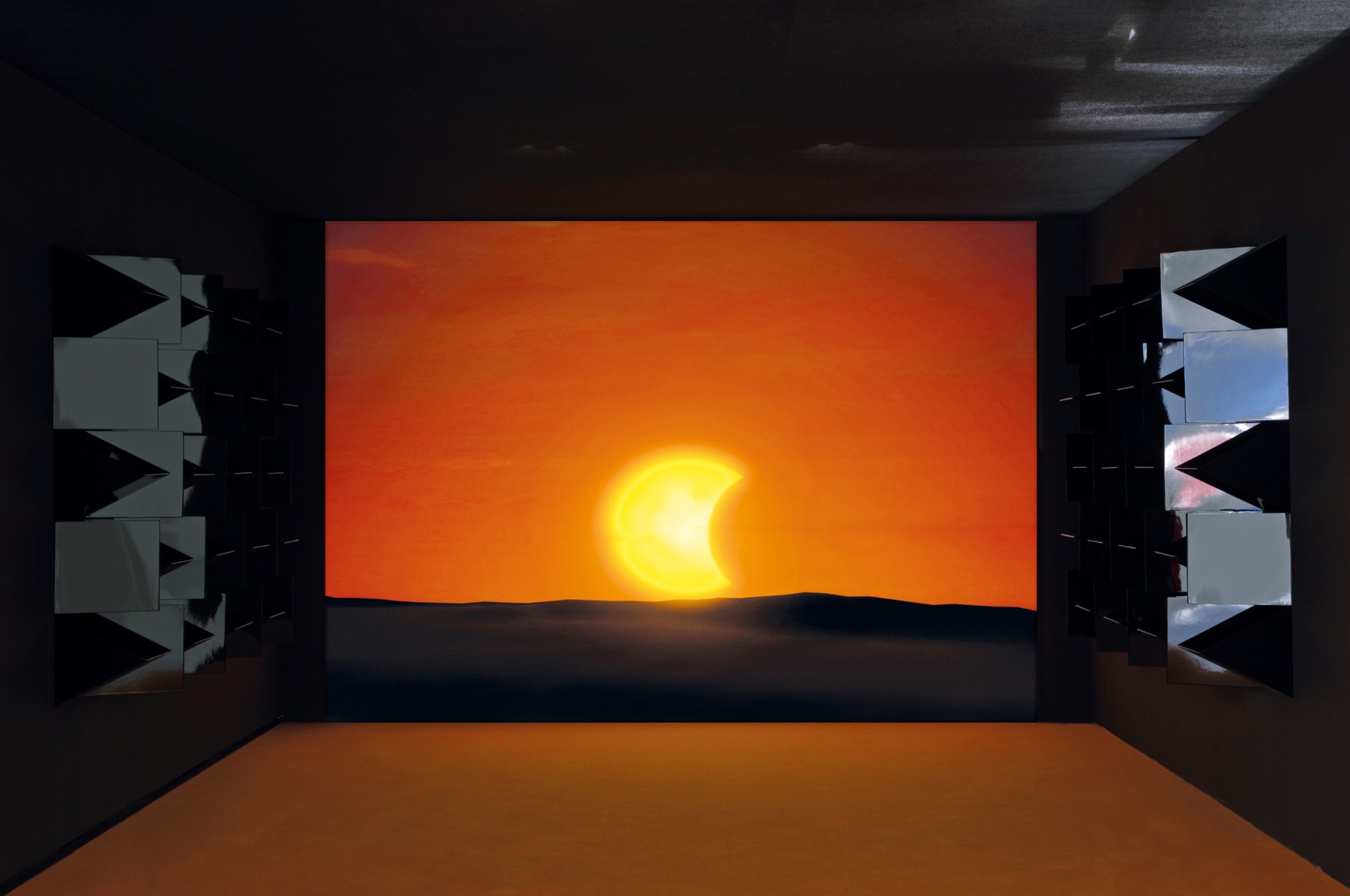

Laurent Grasso, Eclipse, 2006, animation, 10’.

Installation view, Paris, Galerie des Galeries Lafayette, 2008

Photo Marc Domage

Courtesy of the artist

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

For example, in the film Eclipse (2006) Grasso vacillates on the border between belief and mythology, conjuring a false miracle during a combined sunset and eclipse. The film was inspired by stories about various unexplained events, including UFOs and the miraculous apparition of the Virgin Mary in Fátima in 1917, which was rumored by some to in fact be the result of an early-20th-century military experiment. Retaining a healthy skepticism – and making use of cinematic tools of manipulation – Eclipse makes us think on a much wider scale about how modern life is orchestrated.

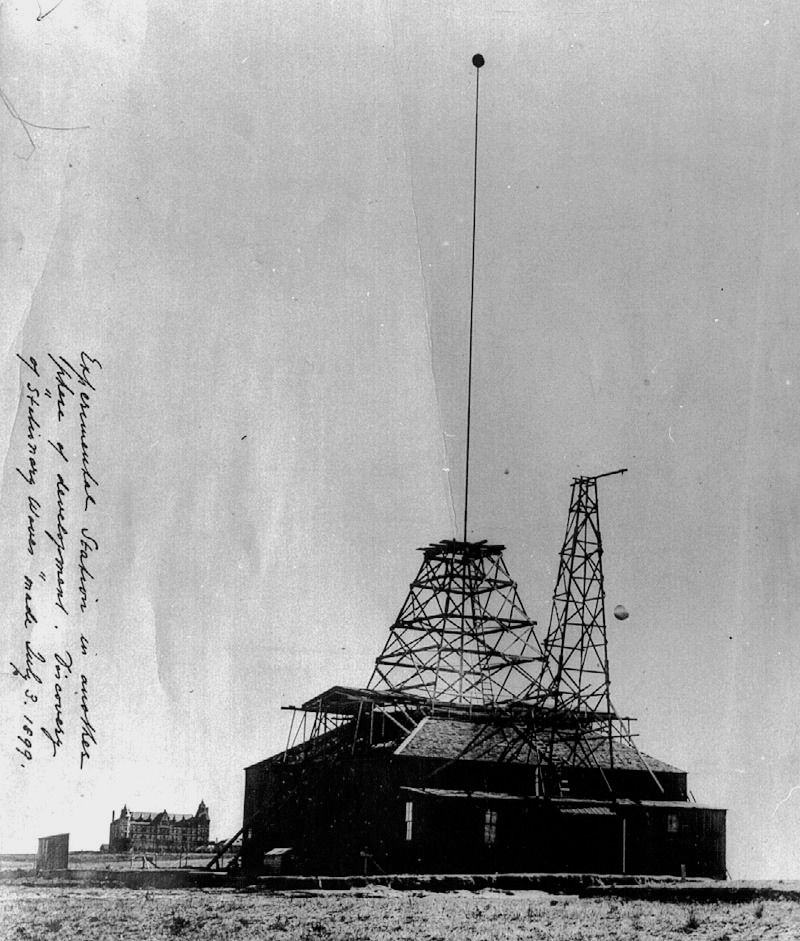

Real and mental space, the material and immaterial, the visible and invisible are all crossroads into which Grasso leads us through his artwork. For example, in The Horn Perspective (Centre Pompidou, 2008), he set the 13.7-billion-year-old sonic remnants of the birth of the universe (so-called “fossil sound”) against the first wireless radio antenna, invented in 1899 by Serbian-American engineer Nikola Tesla. Back then, the antenna was set up in Colorado Springs and was perhaps the first antenna to receive radio waves from space.

Construction of Nikola Tesla’s laboratory in Colorado Springs, 1899, photograph

One of Grasso’s most recent projects, the film OttO (2018), which was commissioned by the 21st Biennale of Sydney, was made in the Australian desert in collaboration with the Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Corporation and the Yuendumu Aboriginal community. It follows and also highlights the Aboriginal cultural phenomenon known as Dreaming, which is a unique way of preserving and embodying ancient stories. Using the modern technology of thermal and hyperspectral imaging cameras mounted on drones, Grasso filmed Aboriginal sacred sites and the mythological (and also physically capturable) energy existing at them. In OttO, this energy has materialised into futuristic, translucent orbs that meditatively and hypnotically slide over cliffs, hills, canyons and saltwater lakes like invisible, metaphorical signs of energy. The film combines a literally dizzying aesthetic, hypnotic mysticism and harsh reality, taking the viewer into a surreal in-between space, into an almost physically palpable present moment in which the past and future have converged into one. A pre-Anthropocene, Anthropocene and post-Anthropocene epoch.

Grasso has received the Meru Art*Science Award in Bergamo, the Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and the Marcel Duchamp Prize. We meet at his studio in Paris, and we continue talking for some time after I turn the recorder off and venture to bring up just a few of his current scientific interests. Among these are Norilsk (one of the ten most polluted cities in the world) and the Global Seed Vault in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, which holds the seeds of 930,000 different plants from around the world, or, in other words, 13,000 years of agricultural history.

Laurent Grasso, OttO, 2018, film, 21’26’’

Installation view at Carriageworks, 21st Sydney Biennale, Australia

Photo silversalt photography

Courtesy of the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Perrotin

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

You once said that you’ve always viewed your work as somewhat anthropological. While filming OttO (2018) in Australia, you studied the mysterious phenomenon called Min Min lights, which is mentioned in Aboriginal myths. In your work Radio Ghost (2003), inspired by paranormal events allegedly heard over the radio waves in Hong Kong, you tried to examine a lost parallel world. While working on Soleil Noir (2014), you began collecting various ancient artefacts, including 19th-century photographs of Pompeii. What do the anthropologist and artist have in common?

For me, art has always been a way to understand the world and be interested in much more than just art as such. I’ve always been in touch with others. I think that to be in other cultures, in another frame of mind, trains the brain to be more open, to have a wider angle of understanding of the contemporary world.

As an artist, it’s important for me to have this link with people from a variety of fields: sociologists, anthropologists, historians, scientists, cinema people. These are spheres that I’ve always been interested in. Anthropology is a way to be in touch with different knowledge, different beliefs, different cultures. But I don’t like the word itself, because it gives authority to the one who’s doing the studying and objectifies the subject. It implies a kind of distance, as if you were looking down from a certain height and with a certain amount of power.

What I understood recently from speaking with anthropologists is that they’ve changed their approach to different cultures. Nowadays they’re trying to co-write the knowledge, memories and culture of the people they work with. They’ve started to become more collaborative. And this is the reason why some anthropologists I met were really interested in what I was doing. They thought it was really close to a new way of approaching an idea. In the meantime, though, I think that, in a way, what I’m doing is completely different from anthropology.

The problem is that this is a very complex territory today because of appropriation. There’s a kind of self-censorship, because as an artist you have to ask yourself whether, if you go to a place with a certain community, you might be seen as taking advantage of that particular culture, of using their culture to do your own art.

Like your own ego thing.

What I try to do is to work collaboratively. I did a project for the 21st Sydney Biennale in Australia at the invitation of Director Mami Kataoka. I was in touch with the Yuendumu community, which is part of the Warlpiri, and especially with a man named Otto Jungarrayi Sims who is an artist himself and the President of the Warlukurlangu Artists Aboriginal Corporation. His father was an artist as well and took part in the mythical exhibition “Les Magiciens de la terre” [Magicians of the Earth] in Paris, in 1989, under the direction of Jean-Hubert Martin.

His community lives near Alice Springs in the Northern Territory and he is a ‘traditional owner’, meaning that he has intangible rights to certain sacred sites and is the story holder of a unique narrative tradition know as ‘Dreaming’. I asked him to help me to get access to these sacred Aboriginal sites and to tell me about their meaning within the limits of the secrecy of their mythology, because a foreigner should never have real access to it. I organised the film shoot with him and he became a character of the movie, as we can see his silhouette walking through the different sites. After that, I created some floating spheres crossing the different sacred sites as an abstract representation of the power of these sites and the secret narratives related to them.

It’s a very sensitive topic, and I tried to be in touch with the people and communities, expressing a very humble interest, a very humble desire to expand my mind and my whole way of thinking by learning about and understanding what other people do and how they think. And even if we will never have full access to the very rich and complex meaning of their ‘Dreamings’, their “songlines” and the map of their reality, we can nevertheless try to understand a lot of things. And it was really interesting, and even quite fascinating to spend some time with them, to learn about this Aboriginal community.

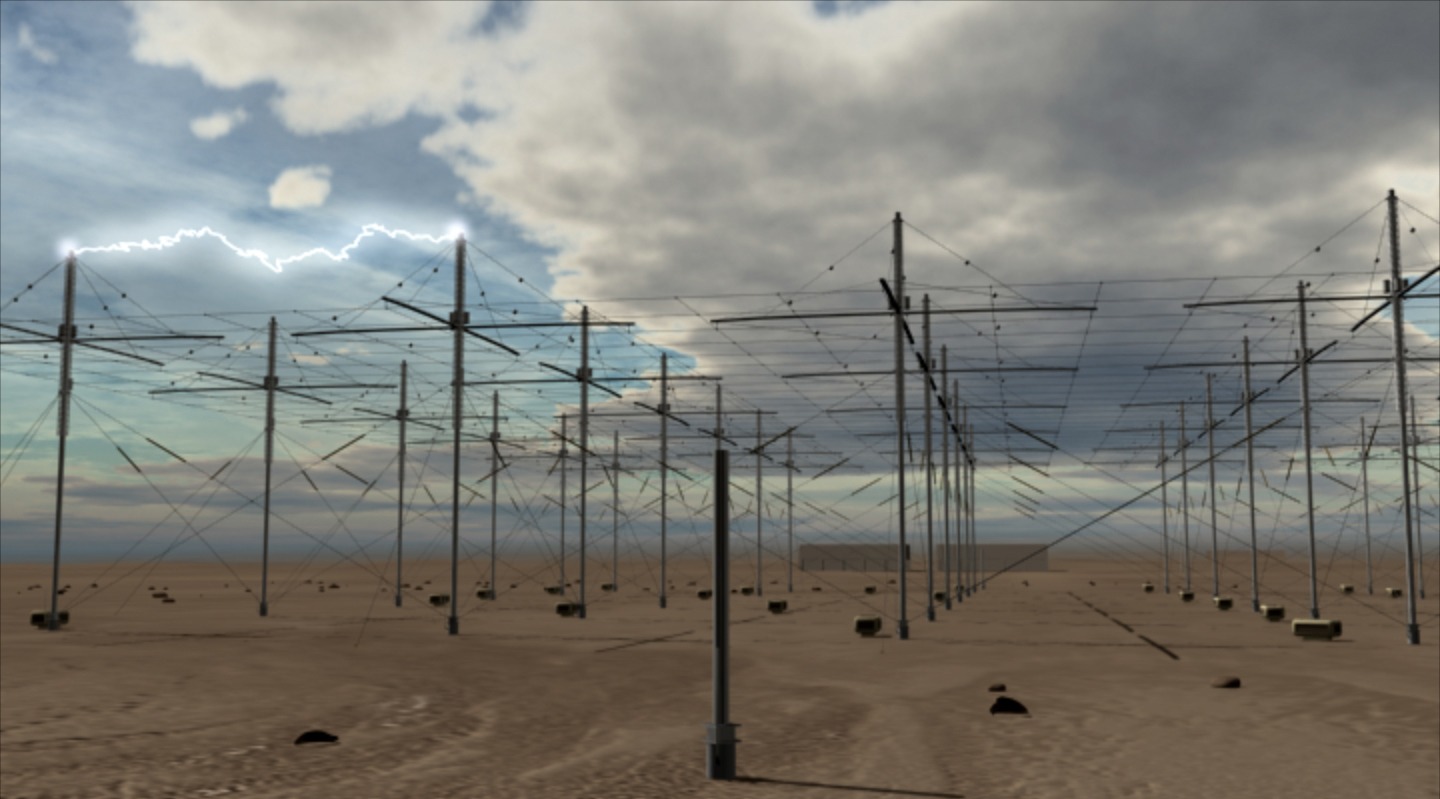

Laurent Grasso, HAARP, 2009

Installation view, Paris, Palais de Tokyo

Photo André Morin

Courtesy of the artist

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

If I understand correctly, Dreamtime for Aboriginal people is a kind of “time out of time”. The Aboriginal land is crisscrossed by thousands of “songlines” that link people to their land, their ancestors, animals and plants.

Basically, they have a very special way of navigating – that you can see through their paintings, which are mappings of their territory –, and they also have a way to navigate through stories with different chapters. These chapters are connected with different key points on the land. It’s really interesting, and they also have a very strong relationship with the universe and the stars as well as a special way of reading the sky. What’s also interesting is that, for Aboriginal people, the gods and various living and non-living entities are more often seen as living in the ground than in the sky.

So, it was a really powerful experience, and this culture in general is a huge treasure. At the end of your life, what you can bring with you are these kinds of experiences, these memories and these meetings with such special people all over the world. As an artist, you do your own art, but through your practice you can also bring the attention of viewers to certain parts of the world, to certain beliefs, to certain fields. You can provide a little spark to excite viewers into learning more about something.

In a way your work is about questioning – questioning knowledge, what we think we know already, showing that there’s always another dimension to it. Why is this important to you?

My idea is not to create decorative objects for forty years in a single way so that people can identify my style. My idea is to provide a kind of experience and to always create something new, always opening the mind of the viewer, and to play and to study brain activity and our connection with our way of thinking. To do that, yes, I make use of different fields of knowledge, different cultural practices. I see the world as something that I can work with. It’s not just me and my studio and objects. It’s important for me to always preserve this capacity to create something new. It’s more of a spirit or an approach that people can recognise, instead of repeating the same identifiable work. I admit that adhering to a single style can be beautiful, but it’s not the way I work.

Laurent Grasso, OttO, 2018, film, 21’26’’

Installation view at Carriageworks, 21st Sydney Biennale, Australia

Photo silversalt photography

Courtesy of the artist, Sean Kelly, New York and Perrotin

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

For OttO, you worked together with scientists and used waves, frequencies, lights, vibrations, memories and the ghosts of one specific place. You tried to discover another reality, a flow that our eyes do not have access to. What did you discover about those sacred Aboriginal sites for yourself while working on this project?

The idea was to use the tools of today to give another vision, to reveal another layer of reality. For example, today we have spectral and thermal cameras, and they can all show different parts of the invisible, such as imperceptible gases. But the OttO project was also a research process. It’s more fiction, of course, but one day it could become reality. Some places just have a certain kind of power; they radiate something special because they are special and they’ve been chosen for a certain reason. And maybe someday we’ll be able to study these places more thoroughly using a variety of parameters.

Those parameters don’t yet exist right now, but the idea of my movie was to try to go in this direction, to show this sacred site with a scientific curiosity, and to use new tools to show what we cannot see, to show the invisible part. And afterwards I also added special effects to have another layer of something I could not show. I’ve always been interested in the strangeness that you feel when you’re in touch with a new reality that you don’t know.

I’ve also studied some strange, unknown practices in other regions, for example in France and Spain. I’m interested in their aesthetics, in the conviction that accompanies these practices and the system that creates them. Like anthroposophy or the “science of mind”, which was developed in the early 20th century by Rudolf Steiner.

I’m not just a simple observer or someone impressed by these things. Nor do I necessarily believe in what I’m studying. It goes back to your question about anthropology. It’s more because I like to understand what kind of stories people need to create in order to survive. I just collect these stories with a lot of distance. I was interested by ghosts, by a lot of things, but I never saw any ghosts. I like to understand the ways in which the brain works.

I was also interested in a Russian scientist called George Lakhovsky, who did experiments in France using frequencies to cure people. His idea was that every cell has its own resonance frequency. When we have certain diseases or problems, the natural frequency of the cell is being disturbed, and thus the cells in our bodies can be regenerated through treatment with electromagnetic waves. To do this, Lakhovsky created a very interesting device in the early 1900s called a Multiple Wave Oscillator (MWO), which is like a spiral transmitting frequency. He discovered that healthy cells act like little batteries, and he found that transmitting energy in the range between 750,000 Hz and 3,000,000,000 Hz could raise a cell’s voltage and thus recharge it.

I was also interested in a form of alternative medicine called radionics. It involves a lacquered wood machine created in the early 20th century by Albert Abrams, a doctor who developed this approach based on radiation emitted by living matter. Radionics boxes were alleged to diagnose all living creatures, from humans to plants, to detect any diseased tissues and to heal them with infinitesimal vibrations. The machine is really interesting, because it’s beautiful and creates a kind of aesthetic in addition to the science, plus there’s belief behind it all.

My vision of art is also closely linked with the idea of the magic object. The idea that something is not just visual but also has a kind of influence. I’m fascinated by unusual objects like radionics boxes, because they also testify to the activity in the brains of the people who created them.

Laurent Grasso, Lakhovsky, 2018, oil and palladium leaf on wood, 117 x 160 cm

Photo Claire Dorn

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

You said that you look at these stories from quite a distance. But as you study more about a particular subject or place, doesn’t this distance between it and you decrease?

I’m more like a filmmaker, and I change fields, countries, and characters. In the end, it’s always the same story but from a different angle. There are some things in the world that first look crazy, and then suddenly they become real and have scientific significance. And this is exactly the kind of territory I look for. So, you’re right. And if we look back at history, it’s always been like that. Because, as we all know, alchemy evolved into chemistry.

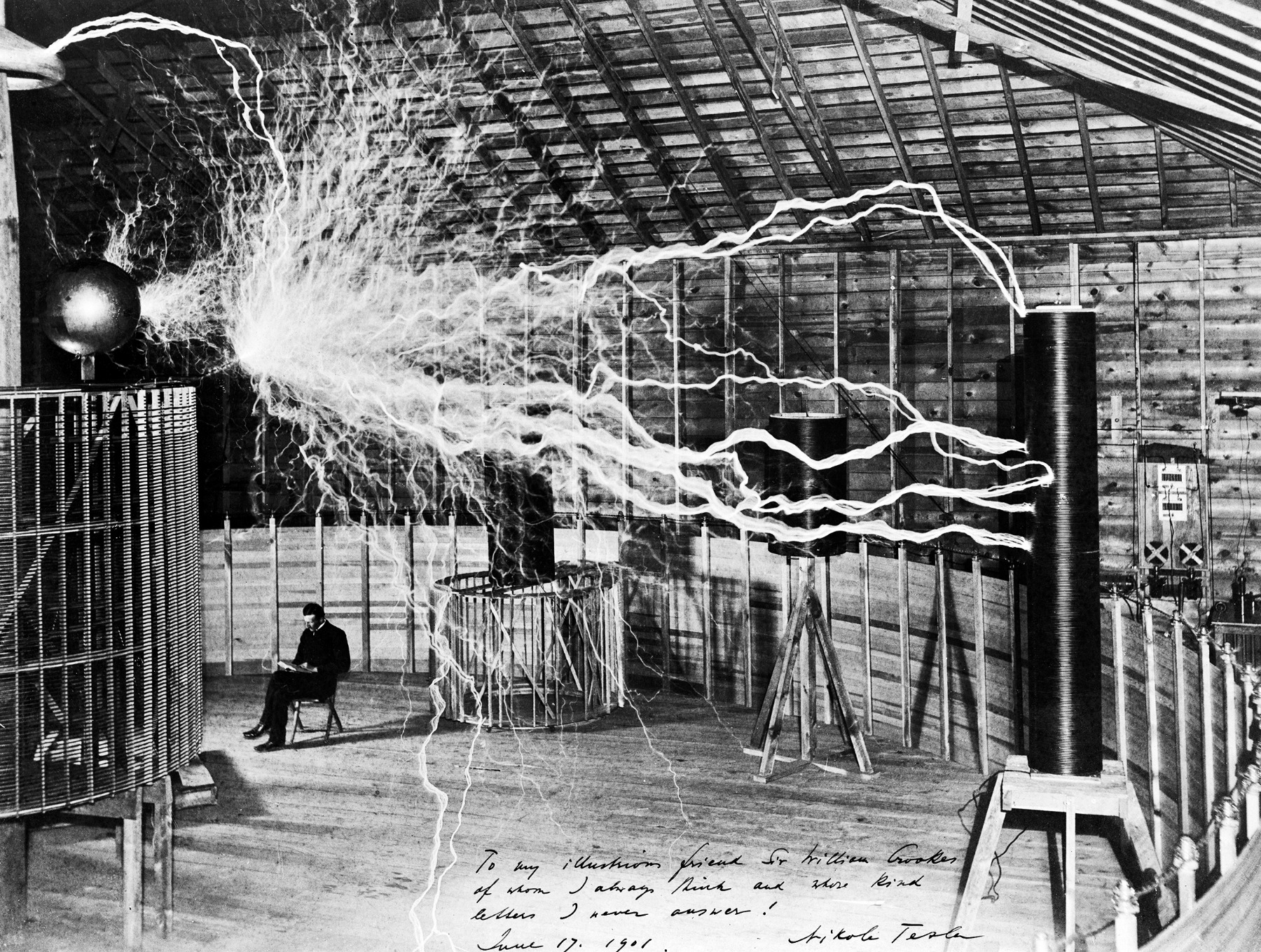

One character I really like is Nikola Tesla (1856–1943, a Serbian-American inventor, electrical engineer, mechanical engineer, and futurist – Ed). He was kind of a scientific poet; he created things from just his mind. Why would anybody one day just start creating a way to transmit the human voice, as Tesla did when he invented the so-called Tesla Coil, which is still used in radio technology today? There was no reason to. But of course, you can understand that it has a function and it’s useful. Tesla also invented remote control and was a pioneer in the discovery of radar technology, X-ray technology and the rotating magnetic field, which is the basis of most AC machinery. This is really impressive, because, in a way, it was all just pure creation.

For example, when I was working on OttO, I discovered the German physicist Winfried Otto Schumann, who predicted – in the 1950s – the existence of electromagnetic frequencies circulating between the Earth’s surface and the ionosphere. These frequencies are extremely slow (between 7.83 and 32 Hz) and were later called “Schumann resonances”. There are also various assumptions about them, and certain curative wave therapies have used these frequencies as an attempt to “harmonize” organs and cells with telluric currents. Some people have created tools to generate this frequency because they believe that if you’re not in touch with the real floor of the Earth, you’re missing energy. So, they try to recreate it, which is very interesting in both the visual and narrative sense.

I think that today reality is very often stronger than fiction. So, my approach is more to work as a kind of collector of different experiments, experiences and different ways of thinking. And through the objects that I create, I share my findings with viewers.

Nikola Tesla reading in his laboratory in Colorado Springs beneath his invention (Tesla Coil), 1899, photograph

And this is why there’s also a kind of hypnotic feeling when looking at your artwork because it places the viewer in a different state of perception. Isn’t this a slightly extreme way of providing food for thought?

In the end, I’m also interested in the way we influence ourselves by different powers. And I sometimes use this capacity of a hypnotizing or mesmerizing situation to show this. It’s a technique that’s widely used in the film industry.

I’m now preparing a project for the Musée d’Orsay here in Paris, which is presenting a show about Darwin in September (“Les Origines du monde. L’invention de la nature au siècle de Darwin” [“The Origins of the World. The invention of Nature in Darwin’s Era”]), and I’m supposed to react and show what the future of the world is. The exhibition will show everything that’s linked with evolution theory in the history of art. And by working on this project I’m going back to a lot of things that I like and that I’ve already approached before.

For example, I did a piece about the Echelon surveillance program network in 2006. I also did a piece about HAARP (High-Frequency Active Auroral Research Program). It’s a very strange place in Alaska, a U.S. military base founded by the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Navy, the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) where you have a field of antennas sending electricity into the ionosphere. But we don’t know exactly what is the real purpose of this military research program.

There are other things like that, very interesting, very mysterious, but also very real things. For example, for the show at the Musée d’Orsay, I was looking for stories about geoengineering, which is not talked about very much. Basically, geoengineering is a way of using technologies to solve the climate issue. For example, spreading sulfur in the atmosphere to reverse the sun’s activity and thus protect the Earth. But geoengineering is also linked with lots of rumors about chemtrails. I recently watched a video about an Italian scientist who went to an airport with a little tube to collect some liquid falling from a commercial airplane and to analyze the liquid from the wings of the plane. And he discovered that it’s full of mercury and zinc. I mean, this is something you can access. But is it real? Is it true or not? I don’t know. But it exists. And you have individuals doing this kind of research, and it’s really interesting. Because they’re fighting to show things that look strange and that we all observe, but we don’t really know about them.

So, it’s in this kind of territory between politics, science and conspiracy theories that I operate. Just mentioning and pointing things out without judging or saying they’re bad or whether they’re real or not. Very often people accuse me of not saying what I really think because they’re used to living with artworks that tell you what you should think. They’re waiting for me to operate in the same way, but I’m not that kind of artist. I’m not pretending to save anybody. I’m just an artist using different kinds of questions and sharing my own questions with the viewer. That’s it. I don’t give answers.

Laurent Grasso, ECHELON, 2007, 19 spheres in stereolithography, black altuglas, black-paintered MDF pedestal

Installation view, IAC Villeurbanne, France, 2007.

Photo Blaise Adilon

Courtesy of the artist

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

I also think viewers have changed nowadays, because we all have more access to this kind of information. For example, you can watch Gaia, which is kind of like Netflix for the spiritual world and conspiracy theories. There are many interesting movies about neuroscience, quantum theory and indigenous knowledge. Things are changing.

Yes. Because people also need beliefs, something to survive on.

What also interests me is that if there’s some information that at the moment is declassified and accessible, that means there’s other information we do not have access to. There’s this TV show about Chernobyl, and it’s very interesting, very well done. But what’s the next story? What’s the story of today? I don’t know. Or we have ultra-rich people building houses in New Zealand to protect themselves in case of a systemic collapse scenario, be it a pandemic, rampaging AI, nuclear war, etc. The plan is to sit out the collapse of civilization. And this is today. For example, the new car created by Elon Musk – not the Tesla, but the other one – is a kind of a war car, it looks like a post-disaster car.

And in a way, my upcoming project for the Musée d’Orsay is a kind of post-Anthropocene. Because the Anthropocene is behind us. It’s too late. So, what we’re doing now is there’s a lot of noise and a lot of activities to save the planet, but no real action. Nobody cares.

Yes, all one needs to do is take a look at the recent Davos forum, where climate change was one of the main focuses and yet the armada of private airplanes on which the forum participants arrived...

This idea of giving responsibility to individuals is just a form of belief. President [Emmanuel] Macron is not able to convince President Trump to sign the climate agreement. Some people know that it’s really hard to change things.

I think the only thing an artist can really do is use his or her work to highlight a problem. As I was working on the HAARP project I mentioned before, I was pointing to something that is maybe 10,000 times more dangerous than plastic bags, because it’s sending a very big amount of electricity into the atmosphere. It’s a wave that some people think could change the climate. There’s an invisible climate war going on.

Also, the story about wildfires in Australia is very strange. I’m not an expert, but what I’ve heard is that there’s an ancient Aboriginal fire management practice. And we filmed this practice – they showed it to us, we were on this land and very close to all of it, and it can be seen in OttO. Fire is normally a way to protect the land because by doing some local fires you prevent bigger ones. But apparently these practices of such local fires have been restricted. And when today everything is burning...well, I’m not saying that it’s not possible to do anything, I’m just saying that my way is to approach the source of the problem rather than just the visible part.

I did a project called Élysée (2016), for which I filmed the Salon Doré (or Golden Room), which is the office of the President of the French Republic at the Élysée Palace in Paris. I was invited to create this work by the Archives Nationales for the exhibition Le Secret de l’État (The Secret of the State) at the Hôtel de Soubise in Paris, and I got authorization to film inside this room. By doing so, my idea was to show where power is located in France and what that setting is like. And seeing this gilded splendor and all the royal regalia, we understand that this place where the nation’s future is decided actually feels very much like the olden days. In a way, it embodies the authoritarian aesthetic and the continuity of power, how it exists above and beyond its incarnation manifested in any one individual.

Laurent Grasso, Elysée, 2016, 35mm film, 16’29’’

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

Laurent Grasso, Elysée, 2016, 35mm film, 16’29’’

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

In recent years many art biennials, as well as more and more exhibitions, are dedicated to environmental and climate issues, but how do you feel about the voice of art itself? How strong is it in our society nowadays?

I think that the real power of art is minimised all the time. Because to be really active, you need to be a part of society. You should have a real voice, not just a place to show art; you need to be a part of the process. I think artists should not only exhibit art but also get involved – they should share their feelings, their knowledge, their experience. They should work on a united team together with entrepreneurs, politicians and scientists. I think this is the way to avoid just being frustrated about what’s going on in the world or just being a creator of objects.

I try to do this, for example, by speaking with lots of people. And I also try to use this approach each time I have the opportunity to show another way of doing things. For example, we do a lot of public commissions, or large-scale installations in the public space. We work with architects, and we try to involve them and show that it’s possible to have the artist as part of the team from the very beginning. Not just to create an object somewhere inside or outside the finished building, but to actually be part of the brainstorming about the globality of the project.

I saw that Olafur Eliasson did a house recently. He built it for a company as a kind of artist-architect, and I thought that was very interesting. I like artists going out of their field and out of their comfort zone. I like this, but it’s more risky.

I think artists nowadays have to reconsider their role. And it really drives me crazy that artists are largely absent from significant projects and processes. In other words, that the museum is the place to “put” artists. In a way, I think that the art world of today is much more conservative than it was before. Of course, you have some big brands that want to have contemporary art, but they want it just as an object and decoration. It’s much more interesting and more meaningful to give the power to the artist to be something else, not just an object maker. And to also be part of the decision-making process and part of the global strategy – to be involved. Unfortunately, that doesn’t happen right now.

President Emmanuel Macron once organised a meeting to which he invited artists, architects and film people in order to discuss the new climate disaster scenario. I thought that was really interesting. In 2009 the Vatican also organised a discussion with artists. It invited approximately 200 artists, filmmakers and architects from all over the world. I was among them, too, and the event was very valuable.

I’m not involved in politics or religion. I am an observer.

Laurent Grasso, Soleil Double in Pompeii, 2015, Fresson print mounted on aluminium, framed in walnut wood, 62.2 x 82.2 cm

Photo Studio Laurent Grasso

Courtesy of the artist

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

Do you feel that this sort of approach could eventually develop further and become self-evident?

It’s difficult. One of my favourite artists today is Trevor Paglen. He photographs secret places in the United States, and he makes the invisible visible by documenting the current American surveillance state. One of his projects is to launch his own time capsule of photographs into geostationary orbit, where it will be available to future civilisations.

Unfortunately, a lot of people today have more power than artists do and do more interesting things than artists do. I’m not one of those artists who loves his field so much that all he wants is to be only with people from the art world. From the very beginning, my vision has been broader. I think this is the reason why I like people like Nikola Tesla. People like Elon Musk, too who doesn’t correspond to the classic idea of a businessman. Because a businessman just does business, but these guys are like builders of new realities, and I like that. People who create companies are sometimes more interesting than artists. The same applies to scientists.

French philosopher Bruno Latour describes Earth in the Anthropocene epoch as “an active, local, limited, sensitive, fragile, trembling and easily irritated envelope”. How could you describe Earth and our current relations with it?

I think Latour is promoting this idea of the Anthropocene so that we may correctly identify the situation. Namely, that there’s an emergency right now. Unfortunately, it seems to me that even the worst predictions have been better than the situation we’re in right now. Like when you see what just happened in Australia – that’s here and now. And it’s really intense. Can we reverse this situation? I really do not know. I’m not sure we can. Besides, Australia is not the only place where fires like that are taking place; there have recently been very big fires in all sorts of places. And destructive storms as well. It was recently planned to open up huge mines in Australia, which is also very dangerous. So, these things are all part of the emergency, part of the ongoing disaster. As we know, catastrophes used to be a relatively isolated phenomenon, but now they are ongoing. It’s endless. And it’s frightening, because reality is surpassing any science-fiction movie.

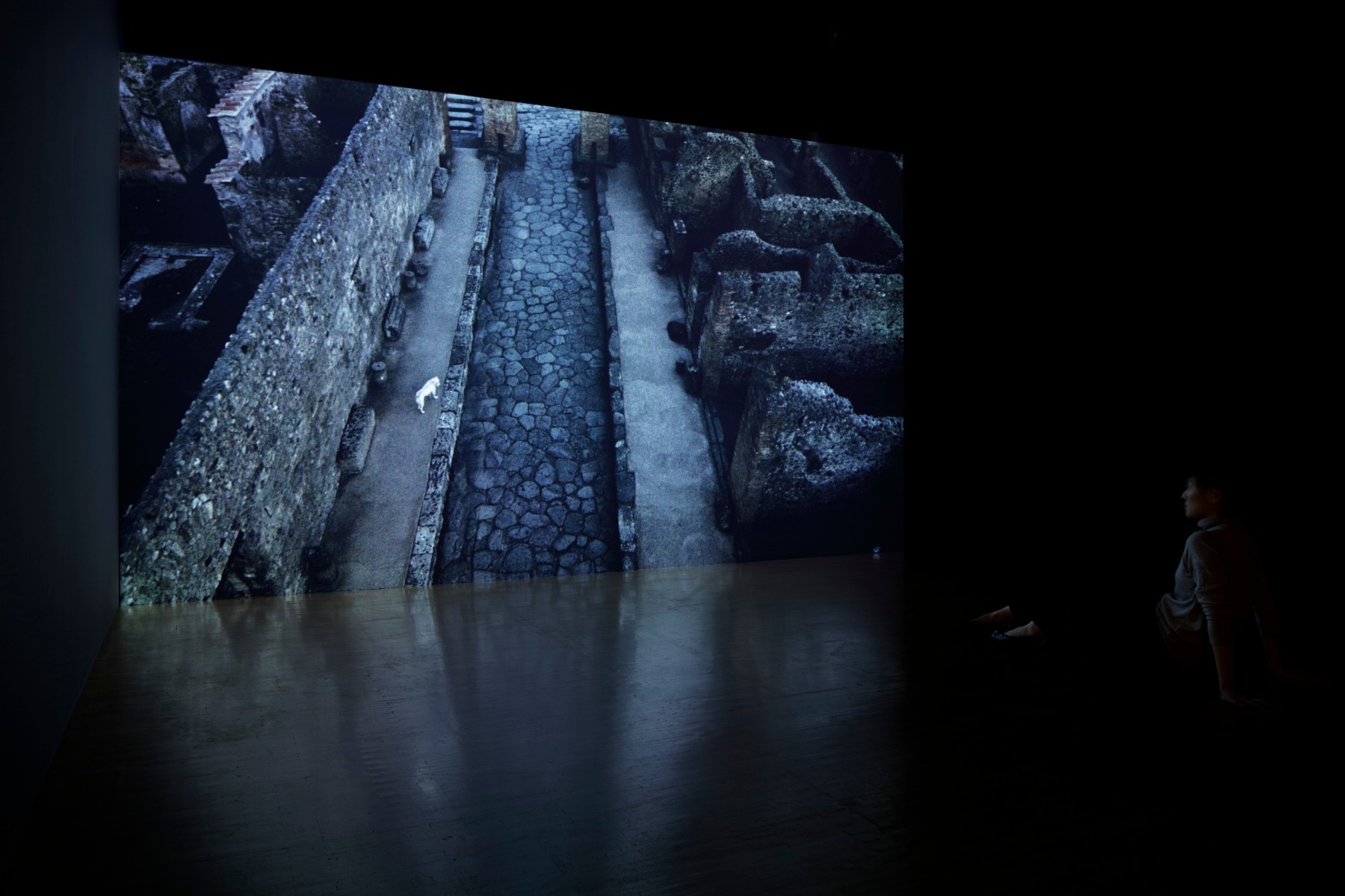

Laurent Grasso, Soleil Noir, 2014, 16mm film, 11’40’’

Installation view, Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, Tokyo

Photo Nacása & Partners Inc.

Courtesy of Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, the artist and Perrotin

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

So, you’re more on the pessimistic side and do not feel that our small actions can change anything on the global scale?

There’s no reason to do things we know are bad. So, individual responsibility can and should be activated. Especially considering the amount of information we have at our disposal today. We know, for example, that it’s bad to eat meat. Or taking a plane – we know that’s not good. There are a lot of things we can change in our own lives. But I’m not sure that it’s going to change the global situation; we need serious government politics to do that. You can try to provide information to others and put your responsibility as a human being in first position rather than just being a foot soldier.

Artists, for their part, should try to be more involved in the decision-making process – not just be an entertaining artist, but to have a voice and use it. Because contemporary art is so trendy today, and we can make use of that fact to change things.

In your opinion, then, the task of artists today – more than ever before – is to encourage people to think, to get involved and, through the use of aesthetic means of expression, to bring the viewer face to face with various parallel realities of the modern world.

Definitely. I try to work with the consciousness of the world and to provide knowledge of the existence of different practices, different ways of thinking, different places or different individuals and also what kind of influences we’re exposed to. I basically try to do my job as an artist, and I try to expand my territory, my understanding and also my network. Not just stay in the little box of the art world.

For example, the Solar Wind (2016) urban project I did on the walls of the Calcia silos in the 13th arrondissement of Paris. We receive daily data about the sun’s activity, and it’s transferred into light and colours on the surface of the installation, which is 40 metres high and 2x20 metres wide and located on the Périphérique ring road. It’s a way to show that we’re exposed to things other than just what comes from Earth. We’re also exposed to the sun’s activity and solar storms. And that’s interesting, too, because it gives you a way to not just think about the Anthropocene but also about the wider frame of our situation. So, I try to share new information I find.

Laurent Grasso, Solar Wind, 2016, permanent light installation, Silos Ciment Calcia, Paris 13th District

Photos Studio Laurent Grasso

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

The role of the artist could also be kind of like a moderator who brings together different disciplines. For example, the soundtrack for OttO combines Earth’s resonance with sacred Aboriginal chants.

Aboriginal people I met were happy to be part of this project which is indeed an artistic collaboration and which was more about making people aware of the existence of their territory rather than pretending to solve their issues. They have a very small voice today, and Aboriginal people are not a common subject. But maybe now, because of the fires, there’s suddenly a lot of attention about their ancient practices.

So, this is a way in which we can work. I’m acting within the framework of an artwork, an artistic form and try to have a strategy afterwards to talk about deeper, more important subjects. We have this capacity to put a foot in the door, and we need to use it. But this is silent work. It’s not something visible. In fact, the more visible it is, the less useful it is.

Laurent Grasso, OLOM, 2018, copper, aluminium, electric oscillator, Ø 2.1m.

Photo Claire Dorn

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

© Laurent Grasso / ADAGP Paris, 2020

Is the world a work of art?

Art should not be art as we normally understand it, but it should be more a part of the world. In that sense, yes, I think that the world could be artistic. And artists should be more interested in the world. Art has to be a tool to understand the world. A tool that people can use. Art has to be interesting and it has to be smart and beautiful, but it also has to provide something. It’s the responsibility of artists to be more in a position to express their real thoughts, to help and to be in touch and not just assume that we’re powerful. And also, to have a desire to be part of this world.